- Home

- Oral Histories

- Former University of Wyoming Football Player Me...

Former University of Wyoming Football Player Mel Hamilton on his life and the Black 14

Oral History Conducted Aug. 27, 2013

Interviewed by Phil White

At the Casper College Western History Center

Casper, Wyo.

In October 1969, University of Wyoming Head Coach Lloyd Eaton dismissed 14 black football players from his team when they donned black armbands to protest certain policies of Brigham Young University and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Mormons. The incident stirred controversy in Wyoming and throughout the nation, and the players became known as the Black 14. Here, player Mel Hamilton shares his recollections with interviewer Phil White, who was a UW student in 1969 and editor of the student newspaper, The Branding Iron.

Transcription notes: Some reference footnotes have been added to this transcript where appropriate. In most cases, redundant ands, ers, uhs, buts, false starts, etc., have been deleted. If an entire phrase was deleted, ellipses were inserted . . . Where you find brackets [] words were added for explanation or to complete an awkward sentence. Parentheses ( ) are used for incidental non-verbal sounds, like laughter. Words emphasized by the speaker are italicized.

~Transcribed by CCWHC and further edited by WyoHistory.org September 2013

Phil White: Ok, there it says record. Ok. They both say record.

Mel Hamilton: K.

Phil: I am Phil White from Laramie [Wyo.]. P-H-I-L W-H-I-T-E. And I’m here with Mel Hamilton, M-E-L H-A-M-I-L-T-O-N at the Western History Center at Casper College. It’s August 27th, 2013, Mel, do we have your permission to record this and put it on the web?

Mel: Yes, you do.

Phil: We’re being helped here by Vince Crolla of Casper College and Tom Rea of Wyohistory.org. Today is the--or tomorrow is--the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington. So we’re here talking with Mel Hamilton about one of the most important events in University of Wyoming history, and perhaps Wyoming history, the Black 14 in 1969. Mel, Mel has a unique perception of this because he originally came to UW to play football in the fall of ‘65, he was then on the starting lineup in 1966 of a team that went nine and one and defeated Florida State in the Sun Bowl. After that, he had a disagreement with the coach and he joined the [U.S.] Army, even though this was the primary period for the Vietnam War.

Mel: Right, yeah.

Phil: He then, when he completed his service in the Army, he returned to the University of Wyoming and again became a starter on the football team for four games when the coach, Coach Eaton, threw the black players off the team. So we wanted to get an oral history from Mel about his life and interactions in Wyoming. I wondered Mel, umm, at the time of Martin Luther King’s march on Washington, you were 16 years old and what do you call about that at the time?

Mel: Well I was in Boys Town, Nebraska [the famous orphanage, founded by Father Edward Flanagan in 1917], at 16. I remember, in our history classes, the priest talking about the Civil Rights Movement. I ever, I was in a period of my life, I was taken away from the black community by going to Boys Town, so I--I didn’t have--I had missed two years of that indoctrination, so I--I didn’t have anything to compare the march to because I was in Boys Town learning a whole new different way of life. And so, it wasn’t that important to me at that time, but as I grew up, obviously it became a very important part of black history and I took more interest in it when I grew up. As a kid, I had no--no interest in the march.

Phil: Now you were born in ’47, in South Carolina, Charleston.

Mel: Charleston, South Carolina.

Phil: What was your dad doing at the time there?

Mel: My father worked for the naval yard, and we--there’s some discrepancy in the family history what he was doing at the Navy yard. Someone said that he was a rigger, and I didn’t know what that was, so I looked it up. And it--it was a person who organized the docks and told people where to go and how to do and so forth. And--and then my dad, I always remember him saying, when I was a child, that he was a machinist. He said, “I’m a highly skilled machinist.” I’ll never forget the way he said it. And--then I heard that he got in a fight with the commander and, in his eyes, was forced to resign. And so he resigned from the shipyard and took the family to what he thought was Wilmington, Delaware, and then woke up and found himself in Wilmington, North Carolina. So instead of growing up a Yankee, I grew up a Southerner in North Carolina, in Wilmington and I remember as a child, we lived in a place called Tank Town when we got to North Carolina, a place called Tank Town. And Tank Town was an abandoned oil refinery, and my dad was successful in getting a storefront building. Used to be a grocery store I think, and we moved in. And that was my beginning in North Carolina.

Phil: What about your schooling there at--the… .

Mel: My mom--well my dad was always a [Roman] Catholic, he came from Mississippi, Natchez, Mississippi. And my mom was a Methodist, and when she married my dad, she converted to Catholicism. And so, being a very devout Catholic, I mean extremely devout, she made sure we were brought up in a religious manner. Made sure that we carried ourselves in a Christian manner and she would drag us to church with her, she went every morning, including Sundays obviously. But, every morning, and drag us with her sometimes. We grew up--I grew up going to Catholic schools. I went from kindergarten through 8th at St. Thomas in Wilmington. St. Thomas was an all-black church; however the priests were white, and I always thought that was kind of different as a child. But I was an altar boy growing up. I at one time thought about, and I think many Catholic boys who are altar boys grow up thinking, that they would someday be a priest. And I thought that someday, I would be a priest. And I say that just to give a groundwork on my demeanor growing up. Very passive, very high achiever, overachiever in most cases. Just trying to do the Lord’s work. I did that until about the age of 13, and at that time, puberty sets in, my mind starts to wonder, I started hanging around with guys drinking wine, smoking, shoplifting and that kind of stuff. And so, my mom said, “No way that’s gonna happen.” And she and my priest, who is--who was Father Swift, S-W-I-F-T, and umm--they worked behind my back to get me accepted into Boys Town. And surely enough the day--the day before I was supposed to go, I was told I was going to Boys Town. And my mom hid it from me ’cause she knew I’d probably try to do something stupid, to run away or something. But it was a gut-wrenching experience at that age, 14, being stolen away, ripped away, from your family. So I went--I went to Boys Town.

Phil: What was the composition in there and how many students?

Mel: There was a thousand students, 500 on the elementary side and 500 on the high school side. There were boys from all over the world--Germany, France, Brazil. All over the world, and very--I think the racial composition was about 80-85 percent white, 10 percent black, and then a mixture of many races--Chinese, I don’t know if we had any Vietnamese, but Chinese, Japanese and so forth. So that was quite an experience for me, because you’re coming from segregated South, where I couldn’t go to the school that was situated literally a block from my house, and then went to Boys Town, where brotherly love, you are your brother’s keeper, all that was taught. I mean taught very earnestly and we lived it every day, we lived it, we took care of each other, we disciplined each other. Boys Town really was ran by the boys at that time. The commissioners and councilmen and so forth. And so we lived that philosophy that we would take care of one another.

I ended up leaving Boys Town with that belief, that--that indeed I’m here to take care of Phil White, to take care of Tom Rea, to take anyone who needs my help. So that’s the demeanor that I left Boys Town with. And it was a blessing, and then it was a curse at the same time, because once I got back into the world, I left Boys Town and went to Laramie [Wyo.]. Once I got to Laramie, I saw that I wasn’t a--I wasn’t received quite good enough, I wasn’t received properly. And I mean by that is, I was stared upon, I was uh--I was

double-guessed all the time as whether I was going to steal something or whether I was going to be just a great-good patron. So yeah, it created a lot of stress in me, a lot of questioning--doubt as whether or not Boys Town taught me the right thing because people weren’t treating me like I was treating them. And uh--it was a tough situation.

Phil: What about your sports at Boys Town and your participation in that government convention?

Mel: It’s a funny story, um, when I was at--North Carolina, going to school, there was no sports. So I had not played sports at all--not organized sports. Of course, we’d have pick-up baseball games in the field and so forth. But there was no organized sport at--when I grew up. So I went to Boys Town and everybody is expected to do something during the summers. You just couldn’t wait around the house and do nothing. Well, I was going to lay around the house and do nothing because I was a loner and didn’t mind being around people, but I preferred to do things on my own. So that’s the approach that I took when I went to Boys Town. Consequently, I got in a lot of fights because a lot of people thought I was stuck up. So I just hung around myself, go and do some adventures and look around Boys Town.

And finally, one of the counselors came to me and said, “Mel, in Boys Town, you gotta do something. You know, you either have to work on farm, or go out for sports, or do something.” And I said, “Well, I don’t want to do that.” And Coach Spencer was freshman football coach at that time and he had heard about me, and someone must have told him that they thought I’d make a fairly decent football player. And he came to the ca--the cottage--we called them cottages--and um--he said, “I would like for you to come try out for the football team.” I said, “I don’t want to do it.” I said, “I’m content doing what I’m doing.” And he finally left and said, “Well, I don’t think you’re tough enough.” And what did he say that for? What did he say that for? He knew exactly what he was doing. I said, “I could beat anybody you got up there.” I said, “I haven’t seen them, but I could beat anybody you got up there.”

Sure enough, I sort of took my time and walked up to where they were practicing, practicing football and just watching from the sideline. Coach Spencer came over and said, “Oh, I see that you want to give it a try?” And I said, “Ah, yeah, I’ll give it a try.” And that’s how I got into sports. Didn’t want to. Didn’t know I could play football. I didn’t know anything that I could do as-you know-organized-wise.

Turned out that I played the game pretty well. And the rest is history there. But there was a governmental system in Boys Town. When I said that Boys Town was ran by the boys, it truly was in those days. We started out with the councilmen, and the councilmen took care of the house and 25 boys. Each house had 25 boys. He would represent those boys to the commissioners, and commissioners would take it to the mayor. I became the councilman of cottage 32, no excuse me, cottage 35. Then became commissioner of the whole choir section and ran for mayor on my senior year and became mayor. So that was my beginning of my political participation. Up to that point, I was very laid back, stayed to myself. If someone was in trouble, I would help them, but I didn’t--I didn’t put myself out front.

Phil: And you also went out for other sports?

Mel: Yeah, went out for wrestling and track and went to state on my wrestling ability. I’ve got real short arms, so the takedown was very easy for me--for them on me. And so, once I got on the bottom, my short arms, they--they had me. But I did pretty well, I can’t--I can’t knock my wrestling, I did pretty well, I did go to state. Didn’t win, matter of fact, I don’t think I even placed at state. But then I went out for track and threw the shot put and the disk and went to state tournament on my shot put, my best was 56 and 3 and 4 quarters, I mean 3 and 3 quarters. And that--that was pretty good in those days. My son beat it when he was in high school. He threw 60, and so that was his mark, all his track career, was to beat Dad. And those were--well I majored in--I lettered in all three, three years in a row, so yeah.

Phil: And how did you, how did it come about that you came further west?

Mel: Well, in those days, and I don’t know if now it’s the same procedure, but the councilmen and the counselors, adults and the director received all your mail. When you go to Boys Town, your parents have to sign their rights to Boys Town in order to make decisions on your behalf. So I was in the custody of Boys Town, they read my letters to see which ones I should receive and which one I should not receive.

They gave me letters from Cornell, Northwestern and Eastern Michigan and so those are the only three scholarships I knew I was being offered. Other people said that they had a scholarship that they never received. So I don’t know if I received more than--than those or not. But those three I did receive and was considering going to Cornell, and was going to go to Cornell, until my best friend, Ken Gilchrist, he got a scholarship from Wyoming. And that was the only scholarship he got, even though he was an All-American center. All-American in the country. And he didn’t get as many as I got.

So he said—well, he didn’t say, Father Wagner said that, and Father Wagner was the director of Boys Town at that time, said that, “You know, Kenny won’t go unless you go,” because we were so close. Wherever I went, you could bet that Kenny was around or vice versa. We just--matter of fact, one of the Omaha Heralds I think, one of the Omaha papers [possibly Omaha World-Herald]said that we were the “Gold Dust Twins” on the football diamond--football field. And truly we were twins, we did everything together.

And so Father Wagner told me, he said, “You know, it’s sometimes better to be”--in reference of me going to Cornell or Wyoming, even though Wyoming didn’t offer me a scholarship--he said, “You know, sometimes it’s best to be a big fish in a small pond,” thinking Wyoming was much smaller than Cornell. So I said, “I’ll give it a try.” Again, you know, this altar boy will do anything that authority told him to do, and so I took that advice and went with--came to Wyoming with Ken.

Phil: And Boys Town helped with your… .

Mel: Yes, Boys Town. I walked on and Boys Town paid my tuition and upkeep for that first semester and then I won a scholarship, and they let me go after that, and I was on my own after that.

Phil: And then, what do you recall about the players that you came in contact with at Laramie and that one year on the varsity, ’66. How was that experience?

Mel: The black players or all players?

Phil: All, whoever you want to.

Mel: Yeah, I, you know, I came with close with [athlete] Byra [Kite], I--and that’s because Byra and I were competing for the same spot. He was just as good as I was. And we just battled and battled and nobody would move anybody, and finally Coach Baker said, “I’m gonna move Byra, I’m gonna move you to the other side.” And that’s how that was solved. And then Dave Rupp was a junior—no, he was a sophomore--when I was a freshman, and Dave Rupp, matter of fact I just emailed him last night. We--we stay close on the Internet, and he’s a good friend of mine. He left Wyoming, graduated from Wyoming, went to Sheridan [Wyo.] and worked in a coal mine as a supervisor. And now he’s in Florida and so we stay very close together. And basically, Gene Huey--who gave me my nickname by the way--and I became friends. And I--I’m the type of person, I can be friends with anyone, and I think I was friends with most of the Black 14.

However, I did not socialize with anyone, black or white. Allen, umm, probably the closest person I socialized with was Allen Gardzelewski, and he’s a lawyer in your town [Laramie]. And he came back from the Army and maybe that was the connection. We were both veterans. He, without a doubt, was my closest friend. And he majored in philosophy, got his law degree from the University of Wyoming.

But I’ve always been a low-key, never wanted to be out front, but as fate would have it, I was always, after the 14, I was always pushed into the front to do something. And I think that’s why a lot of people today think that I was the leader of the Black 14--is because I was always put in a position where I had to step up, and I wasn’t gonna not step up. You know, I was--I told the superintendent [of schools in Natrona County, Wyo.] that I was having difficulty with--in my career. I said, “You know, I just got finished talking to uh…” who was the guy that ran for governor? Bebout. [Wyoming State Senator Eli Bebout, Fremont County, Republican gubernatorial nominee in 2002]

I said, I just got finished talking to Bebout and he and I was talking about me having to fight wherever I go and I said, “I told him what I’m gonna tell you,” you know I’m talking to the superintendent, “I’m gonna tell you, Mr. Superintendent, what I told Mr. Bebout, “I do not ever start a fight. I do not ever start a fight. But I will finish a fight.” And I tried to get that message saying, “Please leave me alone. You know, if you want a fight, I’ll give you a fight. But if you don’t, just leave me alone, and I won’t--I won’t cause any trouble.” And that’s the way I live my life, and unfortunately, there are things that happen that you have to step up.

Phil: Now what happened to Ken Gilchrist?

Mel: Gilchrist! Everybody called him Cookie Gilchrist because of the Gilchrist that played for Buffalo, was it? I think he--yeah, he was an All-American high school, All-American center. He was a shot put- and discus-thrower in track, and he also was a wrestler. He wrestled one weight lower than myself. I’m trying to get the sequence because when I went as a freshman to Wyoming, he was supposed to go. He stayed in Omaha. I went on to Wyoming. I was very distraught because this was the first time this guy and I had been away from each other for four years, the prior four years. So I went to Wyoming on my own.

Later on in the season, he came--I heard a knock on my dorm door, and it was Coach Baker and Gilchrist standing at the door. So we were back together again that first year. Then, Ken stayed about six months, and he had been in the Boys Town since 1956 to 1965, a long time to be at Boys Town and being away from society.…So he was a wreck, a mess. I think that’s why he took to me, because I was someone who--who showed him some interest and stayed with him. To this day, he calls me almost twice a month. But he did not stay in Laramie because of the atmosphere in Laramie and the atmosphere on campus towards blacks. And then he saw also that everybody was against blacks dating whites, and he didn’t like that. And I think he just--his mentality wouldn’t allow him to fight those kind of discriminations without striking back. I mean physically striking back, so he left. He left.

Phil: He played one year on the freshman…

Mel: He played on year on the freshman team.

Phil: He was pretty good?

Mel: Yeah, and he and I were so good on the freshman team that the coaches—varsity coaches--would call us up to help spar against their varsity team. And we did and…we were going through those guys as freshmen; we were just tearing their offense up. That’s how I won my scholarship, I’m sure. And that’s how we got notarized, and it’s too bad that Ken couldn’t put up with the atmosphere and the discrimination. You know, yeah, I saw it as well. But I said, “You know, I’m just gonna do the best I can and hang in there.” Because if it wasn’t for my mom, I don’t know if I would have hung in there, ‘cause she always wanted me to graduate. And if it wasn’t for that, I think I would have left with Ken. And he went to Vietnam, and got all shot up.

Phil: Oh, he did?

Mel: Yeah, and came back, and I don’t think he returned to Wyoming after that. The last--next time I saw him was about 20 years later. He found me in Casper; he was in San Francisco. He gave me a call and said, “Man, I’ve got to make a change.” He was on dope and alcoholic, but yeah, he was on San Mateo police department. He said, “I need a change,” and I said, “Come on down” or “come on up.” He brought his wife with him, and he lived with us for a while ’til they got their own place. He later became a parole agent for the state of Wyoming and retired after 20 years, and now he is in Akron, Ohio. Retired.

Phil: And he--so his career was in Casper?

Mel: His--yes, his career was in Casper. Yeah. So yeah, Kenny was a big part of my life, and really, still is. But he was the only person I associated with. And I--and I don’t mean I didn’t associate with other people, that’s not a bad thing, it’s not in a bad way. It’s just that when I was around him, we got along, we laughed, we told jokes, we were friendly, but after practice, I went my way and they went their way. So, you know, I never, I never ran with them, I guess is the correct way to say it. Yeah.

Phil: Now, something happened after the ’66 season that caused you to… leave Laramie.

Mel: I think… I’m gonna be honest, I think, I think that incident before I went into the military was actually the beginning of the Black 14. I really do. So I guess what I’m saying is: That incident formed my opinion about Coach Eaton that I took with me to the Army and came back two years later in 1969 with--that tainted picture of who he was--and I didn’t like. And at the BSA [Black Students Alliance] meeting where we formed the Black 14, not intentionally, I let that anger out at that meeting and said, “Here is what he did to me.”

So in 1966, the pre-14, if you call it that, when I wanted to marry Kathy Kinne because she was pregnant with my child and I went [to] Red Jacoby, [Glenn “Red” Jacoby, UW athletic director 1946-1973] who was the athletic director--keep in mind the athletic director’s in charge of all coaches--and he told me--I went to him and said I wanted to get okay for married student housing, because I was going to marry this girl. He knew she was white. He said “Mel, that’d be fine, fine, why don’t you go tell Lloyd [Coach Lloyd Eaton] to write the papers up.”

And as I was going into the Field House and Coach Eaton was coming down, we met on the steps and I said, “Just the man I’m looking for, here’s what Mr. Jacoby said, I need for you to write up the papers.” [He said,] “No way, Mel. That’s not gonna happen.” I said, “What do you mean?” [And he said,] “I can’t let you marry this girl on Wyoming’s money. The people of Wyoming’s money.” He said, “Especially the people of Casper, they won’t allow me to let you do this.”

I didn’t know where Casper was; I didn’t know why he mentioned Casper until 30 years later. My wife works for First--well worked for--Hilltop National Bank. The owner of Hilltop National Bank is Dave True. The big oilman. I happened to look on my diploma and whose name is on the diploma, as chairman of the Board of Charities for the University of Wyoming, Dave True. That was the only connection. And I thought about the years, why did he say Casper. I thought, man, that gave me the picture that Casper was the most racist place in the world and why would I want to live in Casper? And 20 years later I found out that Dave True was chairman and he signed--his signature was on my degree.

So what Lloyd was telling me in ’66 was that the chairman would be very upset if I allowed that to happen. And anyway, it didn’t happen. My girl, at the time right after that, before I went in the Army, we were staying together, in Laramie, off-campus, and she gets a call. I’m mad and I’m fuming, pouting and carrying on. And she gets this call that her mom and dad were both killed at the same time. Her parents owned the Elephant Head Lodge in--is there a place called Wapiti? Is there a place called Wapiti?

Phil: There is, a Wapiti, Wyoming.

Mel: Wapiti, Wyoming. And he was--they were riding the horses and trying to cross some river. She got into trouble, the wife got into trouble, he turned back around in mid-stream and they both were killed. He was trying to save his wife and they both were killed. So you can imagine what that was would do [to] a twenty-two/twenty-three year-old person’s mind. So we-we--she went her way, and I went my way. And the rest of the story, she had my oldest child, my first child. Her name was Kimberly. And I went into the Army, of course.

Phil: What were your experiences there?

Mel: In the Army? I was a radio communications specialist. I went from E1 to sergeant. Actually, equivalent is sergeant, but they don’t call specialists sergeant. They just call [it] a specialist 5. I was specialist 5. I made that in 18 months. I was proud of that. I went from--I went from private 1 to Sergeant in 18 months and I was fortunate enough to go to Turkey instead of Vietnam. And I remember the last guy, they went right down the alphabet, and they were sending people all over the world, and they came to Vietnam, and they went down the ages and the guy before me was Hamm, H-A-M-M, and Hamm was the last person in the alphabet that went to Vietnam. Then they started Turkey, and Hamilton was next and I went to Turkey. It was the luck of the draw. I mean, who would have thought? Just one person ahead of me and he went to ’Nam and I went to Turkey. I don’t know what happened to David Hamm, but I hope he made it through. But that doesn’t mean that I would not have gone to Vietnam, I really didn’t have any--any perception about not going to ’Nam or going to ’Nam, I would have gone anyplace they sent me, and willingly. I just got lucky and didn’t go.

Phil: You--were you at all thinking about coming back to Wyoming after the Army?

Mel: No! No, no.

Phil: You thought you were off onto whole new adventures. Toward the end of your time then in Turkey, you did communicate with the university?

Mel: Umm, well, I got a communication from Lloyd Eaton, telling me that--asked me how I was doing in the military and of course, I knew he had also been in the military, and telling me that once I was through, stop by the office and we would talk about things. And I knew what that meant, even though he didn’t come out and say it. I knew what that meant. And so I did, I said I thought I had time to think about it, and I said, “Where else do you want to go?” Right after the 14, you called San Jose, you called those other schools in the WAC [Western Athletic Conference] and they wouldn’t touch you. So where are you gonna go? And so, swallowing my pride, I--I came back to Wyoming.

Phil: But that was bef--you came back in ‘60--fall of ’69.

Mel: Right, fall of ’69.

Phil: After your--were you in the Army two years--two…?

Mel: About 18 months.

Phil: 18 months.

Mel: Mmm-hmm. About 18 months.

Phil: Umm, and so then you had four games, you made your way back into the starting lineup.

Mel: Mmm-hmm.

Phil: And you had four games, you won all four games. At that time, a week before the BYU [Brigham Young University] game, you were--UW was ranked number 12 in the UPI Coaches Poll.

Mel: Right.

Phil: You were undefeated.

Mel: Right.

Phil: And what happened that week then?

Mel: Well, you know, we, everybody was high spirits. The blacks and whites were talking, getting along. And we just knew we were gonna be undefeated, we just knew that. At least, that’s what we were striving for. And the mood was great and high and fun. So we didn’t have--there was very little argument among the white and black players at that time. ’Course you had a few, you know. But, on all in all, it was a good team to be on. So we didn’t have any reason to think that we--that anything was gonna be different.

Now, once we went to Eaton and got kicked off the team, we were highly disillusioned. Highly disillusioned, that the white players would [not] come to our aid. Think, think now. Fourteen blacks, starters in most cases, was kicked off the team. There’s got to be eight starters that are white to comprise the rest of the team, on both sides of the ball. What if they would have said, “Coach, we support the blacks.” What if anybody had protest[ed] on that team that was white? Would that have made a difference? You know, sometimes you think that Lloyd was crazy enough to have said, “The hell with ya, I’ll cancel the season.” And I think he would have cancelled the season.

But nobody tried. I think that’s what hurt. Nobody tried. When I came out to Wyoming in ’66, I drove out with Frank Pescatore. He just gotten a brand new mustang I think, some fancy car, and he lived in Passaic, New Jersey, I think. And my sister lived in Patterson, New Jersey. So I was visiting her and Frank and I bumped into each other working out one day in Patterson in high school. And he said, “Why don’t you drive back with me?” And we drove back from New Jersey to Wyoming. You know, we were, having a great rapport. I would think--he would have said something.

Phil: Was he still there though in ’69?

Mel: Yeah, he--matter of fact, he started an insurance company there when--after the ’69, in Laramie. It was on Grand Street in that hotel? So I don’t know if Frank is still there or not, I hadn’t heard any more about it.

Phil: I don’t think so.

Mel: But if they would have said something, maybe they could have--we could avoid this whole experience, but they didn’t. And so, that was the extent of the white players helping us. As far as I know, nobody did anything. Not even my good friend Dave Rupp, and I love Dave Rupp. And I’ll tell you right now, even to this day, I love Dave Rupp But, even he didn’t do anything. Well, the only [thing] Dave would say is, “Man, you know he’s crazy. Why did you guys do it? You know he was crazy.” You know.

They had--Dave told me stories about Lloyd Eaton having a blackjack in his--in his drawer, and that’s that thing that cops have with a weight into--a weight sewn into a leather pouch--they call it a blackjack. It’s like a baton really, except leather and steel. He kept that in his desk just in case we got out of line. Any of the players got out of line. He said, “You guys know he was crazy, why did you do it?” And I was disappointed in Dave for saying that, but he--he still remains one of my dearest friends. So.

Phil: Umm, well tell what--what happened on that Thursday, Thursday night, and then the Friday morning, as best you recall.

Mel: Thursday night, when we decided to wear the black armbands?

Phil: Yeah.

Mel: Uh, after the meeting, well at the meeting, and that’s why I say the ’66 incident with me and Eaton was the pre-Black 14, cause during that meeting [with the other players], I said, “Look, here’s what happened to me in 1966. Here’s why I went into the military. I know what the man can do. And if you don’t do anything to--to support this--to fight against this Mormon policy,” I said, “They will continue to do these kinds of things to me, to you, to all black Mormons. They will continue to try to run you over.” I mean I was vocal. And where did that come from? I don’t know. I don’t know where that came from. But I’ve always been thrown--at least I think--I’ve always been thrown into doing something.

Phil: Uh-huh.

Mel: So all that came out. And we decided to go to [Black 14 member] Joe Williams’s room, talk about what we’re gonna do. We gave the--the guys that had wives and kids an opportunity to back out and nobody backed out. Everybody said they wanted to do it, and we had to do it. We were caught up in a moment of history with a social revolution happening outside of Wyoming. Outside of Wyoming. So we--everybody’s out there doing their part. [Olympic sprinter John] Carlos and [Tommie Smith] were doing their part at the Olympics, and--I personally, I personally couldn’t have stand not doing anything.

This opportunity came before us, we had to grab it, it was our turn. We had to grab it. And that was me. And like I said, I don’t know where that came from, it was--it was bottled up for two years and it all came out that night. And so, we went to the room, and we talked it over and everybody said, “Let’s go.” And I was talking to Tom Rea over lunch today, and I said to Tom …so we decided to wear the armbands. Now, think about this. And I only thought about it over lunch.

We were under the impression that Eaton said, “Don’t wear your armbands, you will not be allowed to wear your armbands in the game.” That was our impression. We did not think by wearing our armbands to the office that he would be offended. We wore the armbands to the office because we wanted to show solidarity. So if Eaton had given us an opportunity to speak, he would have said, probably, “Oh no, you want to wear it during the game? Oh hell no, you’re not gonna wear it to the game.” We would have said, “Ok, what can we do?” And then we would have had a dialogue. We would have came up, hopefully, we would have come up with something we both would agree on. Whether that was getting together in the middle of the field before the game, saying a prayer before the game, something to make a statement, but he didn’t allow that to happen. So.

Phil: Wha--what did happen?

Mil: Well, uh, he took us to the bleachers in the Field House and sat us down, and the first word out of his mouth was, “Gentlemen, you are no longer on the football team.” And then he started ranting and raving about taking us away from welfare, taking us off the streets, putting food in our mouths. If we want to do what we want to do, we could [go] to the Grambling [College] and the Bishop [College], which are primarily black schools, historically black schools.

And so he--he just berated us. Tore us down from top to bottom in a racial manner. I remember looking at him right in the eyes and the whole time I’m thinking about 1966 and looking at him right in his eyes, smiling. I did not let that smile break, because I wanted him to know that he wasn’t--I wasn’t a little kid anymore. I’m not frightened of you. And you’re not gonna stop me from doing what I think I should do. And I know then that he was—he was constitutionally wrong, even though we weren’t prove—we didn’t prove that that was right, but I wanted him at least to know that I thought he was constitutionally wrong and was going the wrong way, and it wasn’t gonna frighten me.

Phil: So, you left there, and later that day, they called a meeting of the trustees and after that meeting, did any of the Black 14 actually have a direct interaction with Eaton that day--the rest of that day?

Mel: The rest of that day? If they did, it was not to my knowledge.

Phil: I think then, what I’ve always heard is that the trustees and the governor were there, they met with the players, and they’d meet with the coaches separately.

Mel: Well, the trustees with--yeah, I was at that, that meeting. And you’re talking about the midnight meeting?

Phil: Yeah, yeah, went ’til 3 a.m.

Mel: Yeah, yeah and Governor Hathaway, I was sorely disappointed in him. Uh, he had the ability, of course politically, it wouldn’t have been a good decision, but he had the ability to stop it, right there and then. And I think that when someone asks, would we play for Eaton without wearing the black armbands, one of us said no, and I don’t know which one of us said no. I think once we said that, the governor said, “Well, that’s it. You know, basically, our hands are tied. And we’re gonna support Eaton.” I think they were, of course, supporting Eaton way before that statement was made. But yeah, we did meet, and I remember walking out and saying to the reporters when they asked, “How was it?” And I said, “It was all-white. We didn’t have a say at all, it was all-white.”

Phil: So then what was the reaction the next--the next week?

Mel: Uh, boy, you can imagine, we had--we had national coverage. We had media from all over the area--all over the country. I remember a group of umm, these things just pop into my head, I remember a group of ministers from all walks of life, and even Darius Gray, the black Mormon, they sent down and tried to talk to me. And I, I was gonna talk to them. And a black media, had to be from Washington D. C., in that area, looked at me and shook his head. And I said, “You don’t think so?” And he said “No.” So I didn’t talk to the ministers that came to talk.

Phil: Uh-huh.

Mel: And so, I had--I don’t have any knowledge what they were gonna talk about. But, umm, yeah, there were people all over wanted us to make quotes. I got a call from--well, actually [BSA member] Dwight James got a call from Berkeley, a radio station on [the University of California at] Berkeley campus, about what was happening in Wyoming, and “Would you [tell] our audience what was happening?” Dwight came to me, I was in the Union, [UW student union building] and said, “The people in Berkeley want to talk to you.” I don’t know whether they did or not. I think Dwight, you know, he was gonna be doctor and was gonna be in the FBI and probably didn’t want to get involved that way, and he said, “I do know somebody who will talk to you,” and obviously, he picked me and I talked to them. So everybody all over the country was calling and sending their people and it was very hectic, very hectic.

Phil: You stayed and got your degree.

Mel: Yeah.

Phil: From UW.

Mel: Yep, physical education. I remember, I graduated in ’72 and by that time, I had been married to Tearether Cherry and everybody called her Chi-Chi, that was her nickname. And she had a semester to go, to finish up, and so I stayed in Laramie. Finally I said, “I need to make some money.” So I found my ex-Boys Town boy, living in Denver, who was a bigwig with Shell Oil Company and asked if he had a job for me until my wife graduated, and he gave me a job and I stayed there for a month--I mean a semester--and when my wife finished up, went back to Laramie, picked her up, packed her up and took her back to North Carolina.

And then she, of course, being a Casper girl all her life, had a very difficult time adapting to the southern ways. She didn’t like the people, she didn’t like the climate, she didn’t like the roaches and she was constantly complaining. Wherever we moved, there were roaches. I said, “Babe, there’s gonna be roaches down here.” And I said, “I’ll tell you what, they built some new condos over here, we’ll get one of them and see what that does.” And of course I knew. You know, you can’t find all the eggs of a roach. When you move, you gotta make sure you do not bring an egg. Not one egg. And obviously, we got in that new condo, and sure enough, six months later, there they were. And it didn’t matter whether you had no eggs or not, the person next door to you could have eggs and they would get into your apartment. And so, she came back to Casper, like I said, she had my first boy born, and I didn’t want anybody raising my kids but me. And so, a couple months later, I told Corning Glassware, who was I was working for as a mid-management supervisor, that I was going back to my wife. And so, a good job too, that was the best--one of the best jobs I ever had.

Phil: And she was a graduate of Natrona County [High School in Casper].

Mel: Yes, graduated from Natrona County.

Phil: And what did her parents do?

Mel: I think they were just… Dorothy Bourough B-O-U-R-O-U-G-H worked at the library. I think she was just a cleaning lady, I’m not sure. Didn’t have a dad. So she came down and ah, I remember when she came down, the--my second semester or my first semester. My second semester. I was standing at the line [at UW] at Old Main.

Phil: This is uh, in like 1970, spring semester of ‘70?

Mel: No, she was there for the 14, so she must have been the same 1960--no it wasn’t ’69. Had to be the first time I was here. Wait a minute. Uh, it had to be after I came back from the Army, and before the 14. We were standing, registering, in front of Old Main. I was with, I’ll never forget it, I was with uh, Father ????? in Hudson. [Wyo.]

Phil: Svilar?

Mel: No, uh.

Phil: Oh, Vinich.

Mel: Vinich! I was in line with Vinich, the son. I said, “Man, who was that you were talking to?” He said, “Oh, that’s Chi-Chi, you want to meet her?” And that’s how I met my first wife. John introduced me to her and ah--and then we started going together immediately, and we got married after the Black 14 happened. Oh, I would say, that next August. That’s how--that’s all that happened, John Vinich [later a longtime state senator from Fremont County]. I sometimes curse him for that.

Phil: So, your wife and the bed bug--or the roaches brought you back to Wyoming.

Mel: Yeah, and uh… .

Phil: What did you do here?

Mel: I came back uh and I worked for--I went up to the Natrona County headquarters [Natrona County High School] and applied for the teaching job. They didn’t have any positions, so I worked as an assistant manager for Kmart in their appliance department and worked at night at the Star-Tribune as a baler. And…then, uh, a coach from Kelly Walsh [High School in Casper] retired--not retired, he quit…They called me. And I started out just as a replacement for him, and of course, they couldn’t promise me whether I’d have the job the next year or not, but as it worked out, that was my foot in the door, and I did get the job.

Phil: And what were you doing there?

Mel: And I was a P.E. [physical education] coach and coach. Yep, in football and wrestling and track. I remember I was trying to make $12,000, and I just barely made $12,000 teaching and coaching three sports. And to me, that was the barometer of being a success, getting to that $12,000 mark. My first salary--I mean contract was for $8,645. I look back on that and say, “I don’t know how we made it on that.” But we did.

Then in the meanwhile, my wife and I were not getting along, so we ended up divorcing and I--in ’77--and I quit teaching. I got--couldn’t handle it, the divorce. Keep in mind, I’m a Catholic, altar boy, I mean Catholics had--did a real good job on me, and divorce was, it was the last thing you wanna do. And…it tore me apart. And so I quit teaching, I couldn’t concentrate at all. And went into the oil field and--turned out that was a pretty good move. I had a good time, I made a lot of money, bought my first house, umm, it gave me another possibility on what I could do. And …my self-esteem.

And so when the bottom of that oil field fell out in ’86, I went back to teaching, started it over again at Roosevelt High School [in Casper]. Dr. Carl Madzey had--had heard about me and followed my career and asked me to come over. And that was in 1986, and then I went to Kelly Walsh as a P. E. instructor, see I didn’t say that the first time. As a P. E. instructor in ’88 and coached football, wrestling and track over there.

Got my masters in ’92. Dr. Madzey said, “Now you’ve got to work with me. You got your masters, exactly what I need. And I need an assistant principal, now you can do that for me.” So I go back to Roosevelt in ‘92, got my masters, I’m working with at-risk kids again, I’m enjoying it. I became the vice principal of Roosevelt, the first time they’ve ever had a vice principal. Over the years, worked myself into administration, in 1996, became a principal at East Junior High School [in Casper] and that was a terrible time in my life. ’96 and ’97 had to be the worst years in my career. Even over the Black 14 incident. That was because I was not given the chance to run a school the way I thought a school could be run.

And I wasn’t given the chance because when I applied for the job, two of the principals--vice principals at the time--currently in the vice principal role, were vying for the same position. They did not get it. I knew immediately, when I found out the two had ran for the principalship, I knew immediately I was in trouble. And I took them out to lunch, and I said, “Look, I know you guys tried out for the position and didn’t get [it]. I know how that feels, you were in a building, you build up trust and they didn’t give you the opportunity to work as a principal.” I said, “But, however, we can’t let that stop us from being a successful school.” I said, “I need your promise that you will--you will work with me.” Well, one of them did. That was Stutheit, Brad Stutheit, did not hold any animosity. If he did, he didn’t show it with me. He was very respectful. Did his job, didn’t show anything.

But the other guy was the snake--was a timber rattlesnake. He was just working behind my back, having special meetings at lunchtime with disgruntled employees, other teachers that didn’t want me. And I thought, I think they didn’t want me because I was black, I was being called the head nigger in charge. Someone stopped by my house when I wasn’t there, snow on the ground, and there was a big “666” written in the snow in front of my house. They were passing around jokes about E-Ebonics, trying to play at my manner of speech.

One of the counselors there said that it was a concerted effort to get me out of there. Concerted effort. And then, I didn’t know of course, all these things were happening, until about eight teachers came to me one day and said, “We need a meeting with you,” and told me what was happening. And as I stated many times before, the worst part of all of that was that when it came time for me to sit down to evaluate my performance, I couldn’t because every time I tried, I would always interject, but if this racism didn’t exist, that would have happened, this would have happened.

So I never could--could fully evaluate myself as to my progress. And I--and I truly wanted to be able to do that, because I think I would have had the ability to say, “Mel, you should do something different here,” or “You’re doing something wrong here.” I have that ability to do that. I couldn’t in this because the racism kept popping up. So that’s what they took away from me. So, did I do a good job? I think I did, but I don’t know.

Phil: So how long were you the principal then?

Mel: Umm, ’96 to ’99, and then there was so much heat, they moved me from—they caved in to the politics of it--and moved move to a new program with at-risk kids, cause that was my forte. And they said….

Phil: And how--so how long was your career in public schools?

Mel: 28 years.

Phil: 28 years.

Mel: Yeah.

Phil: Retired when then?

Mel: I retired in--in 2011.

Phil: So tell me about your family and your wife--your current wife--and kids in…

Mel: Yeah, I got--matter of fact, Carey C-A-R-E-Y, is my current wife of 33 years. She is a Wyoming girl from Osage.

Phil: Oh really.

Mel: Yes. Of course her friends and my friends both, because we were so different, didn’t think it would last a year, and 32 years later, here we are. She is a--is a very understanding, very loving person, and I think that’s what attracted to me, she didn’t--my race wasn’t an issue. My race was not an issue. When I went out with her, she was concerned about other people--the people that came up to say “hello,” which were many. I was impressed by that, and that further told me she was a good person.

We got together and had two kids, Malik and Zella. And then of course, I have my oldest daughter in California by Kathy Kinne--the Wyoming incident young lady--and she had Kimberly, my oldest child. And then Carey and I had two, and Chi-Chi and I had two, Malik and Amber. Carey and I had Derek and Zella, and then Kathy Kinne and I had Kim. We been together ever since.

Phil: And they’re all doing… pretty….

Mel: All doing well, yeah. Kim, uh, as I once said, she is—ah, was in an all-girl fire unit in San Francisco. I’ve got a picture of her—well, she’s got a picture that I want, of climbing the San Francisco Bay Bridge. Man, what a beautiful picture that was. Malik, my oldest boy, is in Provo, Utah. He became a Mormon after much, much consternation. He thought that I would be very angry, and I don’t know why he thought that, because I was fighting for the right of blacks in the church to do something, to be able to do something. So he’s a Mormon chef, working at University Valley, Utah Valley University, in Provo, Utah. And then I have Amber, who is a director of Home Shopping Network down in Florida and a buyer. She buys a lot of their stuff. And she’s in Florida somewhere now. I can’t remember if she was in… Disney World, where is that there?

Phil: Orlando?

Mel: Orlando, she was there at one time. But I don’t know if she’s still there, but she’s in Florida. Um, uh…

Phil: Derek.

Mel: Derek is working for Weatherflick, no. Weatherford. An oil patch, and he really enjoys it. Matter of fact, he’s sort of jokingly asked why I didn’t tell him about the oil patch before he got into it because he really enjoys it and didn’t know it would be that much fun. Umm, Weatherford got him under a five-year contract to be management, to be in their management program. Just got a raise, he said the other day, and he’s really having a great time. They’ve sent him to Houston for many schools, to certify him in all things he needs to be certified in. And then Zella, we just found out unfortunately, found out that she has the M.S. [multiple sclerosis] and she’s back home with us. And the way we found out, that she came home one day and the whole left side of her face had drooped. And I thought she had a stroke and her doctor thought she had a stroke too, and that’s how we began to find out that she had M.S.

Phil: Oh, dear.

Mel: And so she’s back home with us, and her baby girl, Maya, she is my heart these days. She keeps me going, and I love her dearly. And so, that’s my family.

Phil: And they have--and you have five kids, and they have, uh eight….

Mel: Eight grandchildren.

Phil: Grandkids.

Mel: And Derik has one on the way. But thank God, no, no great-grands yet.

Phil: Ah. Hope that happens.

Mel: Hope that happens in it, in its time.

Phil: But uh… .

Mel: In its time.

Phil: But you’re facing some challenges in the health department. . . .

Mel: Yeah, I’ve ah--my, my whole retired family, my side of the family, had problems with diabetes. And most were sorta heavyweight, but even the ones that aren’t heavyweight has diabetes. My mother lost her--a foot because of diabetes. My sister lost both legs because of diabetes. It’s just a vicious, a vicious disease. Umm, and I’m having problems with it, I’ve gotten gastroparesis, which happens to a lot of diabetics and that’s basically saying that my stomach does not empty its food in a timely manner. Takes too long, the food or the fluids, to exit my stomach. And it causes many different symptoms.

I can’t literally lift five pounds or walk a half a block because of it, and that’s causing problems ’cause I gotta exercise to lose the weight, and I can’t exercise. Ah so, as I’m trying to get the lap band to help me lose weight, and the doctor said they usually can’t do that on people with paresis. Because you can imagine, if you shut down half of the stomach with the band, then that paresis is working on--only on half the stomach and it’s gonna be just as bad. It’s gonna be doubly as harmful to me as it is now.

So we’re trying to figure out what’s wrong with me. I--uh having a tough time walking, I don’t know what that is. I had back surgery thinking that it was spinal stenosis, and I got a second opinion that said it was spinal stenosis. And it turns out that it wasn’t spinal stenosis, because I got the same problem. I can’t walk more than half a block or three quarters of a block without stopping. My muscles feel like they’re atrophied, and I don’t know--you know, I remember five years ago, walking all over Atlantic-Baltimore and Savannah, Georgia, and all of a sudden, I started having a problem walking. Now if it was then that I’m thinking, “If my daughter’s got M.S., maybe I got M.S.” So, I’m going to have that looked at. ’Cause that’s the only thing I can think of.

Yep, so I’m not doing too good these days. I know I gotta lose weight, but the insulin puts weight on ya, and umm, you know, and I can understand how people feel when they gotta disease that stops them from losing weight. Then people--other people think that they’re lazy and just won’t do it. I can understand those people now. It’s--it’s a vicious circle. If I don’t take my insulin, my sugar goes up. If I take my insulin, it puts weight on me. So what do you do? You take your insulin, and you get bigger and bigger and bigger and so, especially when I can’t exercise. That’s the problem. Exercise, not being able to, is the problem. It’s not the insulin, it’s not the eating, it’s not being able to exercise.

Phil: Well, I hope that works out better for you.

Mel: Well, I’m gonna, I’m gonna get, I’m not gonna stop with the doctors. Somebody knows how to--how to help me, and I just have to find that person.

Phil: Sure, yeah. Well, Mel, it’s certainly been a pleasure talking with you.

Mel: Well, I hope we covered everything. ’Cause--that we covered the first time.

Phil: All right. I wish you the best, and we’ll keep in touch.

Mel: I will, umm, and when you gonna write that book?

Phil: Well, I’m still thinking about it.

Mel: Well, you should, I was telling Tom Rea over lunch, I said, “If anyone,” I said, “you’re like the pivotal point of this whole story, and if anyone should write a book, you--you would know the ins-and-outs of this 14 thing.” And I really mean that. Even if I write a book, it’s gonna be about my growing up in--in and how I got into this 14 thing in the first place.

Phil: Uh-huh.

Mel: But I wouldn’t be able to write it from your perspective. You know, so.

Phil: Well, see what we can do.

Mel: Yeah, k.

Phil: K.

Mel: All right man, is your wife out there prob-

Resources

Illustrations

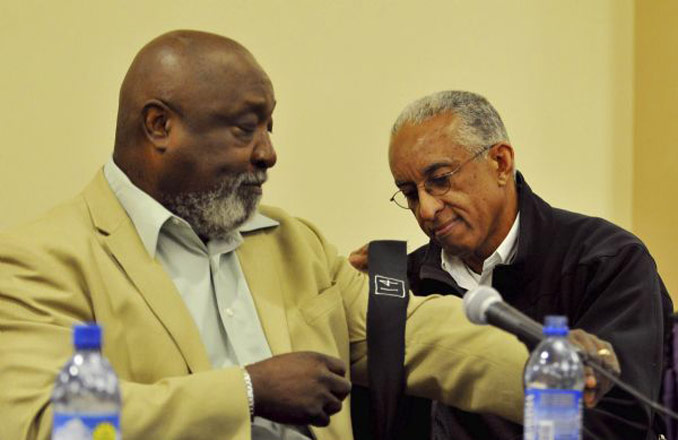

- The 2009 image of John Griffin tying an armband on Mel Hamilton is from the Laramie Boomerang, photo by Andy Carpanean. Used with permission and thanks.