- Home

- Oral Histories

- Dr. Willie Black, Chancellor of The Black Stude...

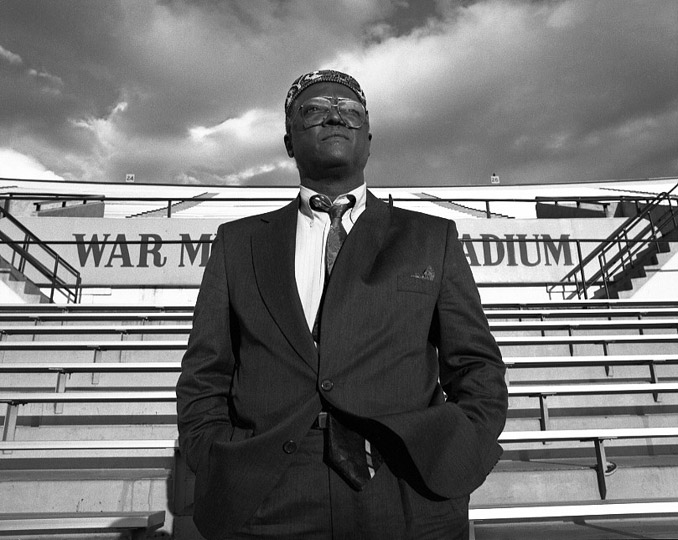

Dr. Willie Black, Chancellor of the Black Student Alliance in 1969, on the Black 14

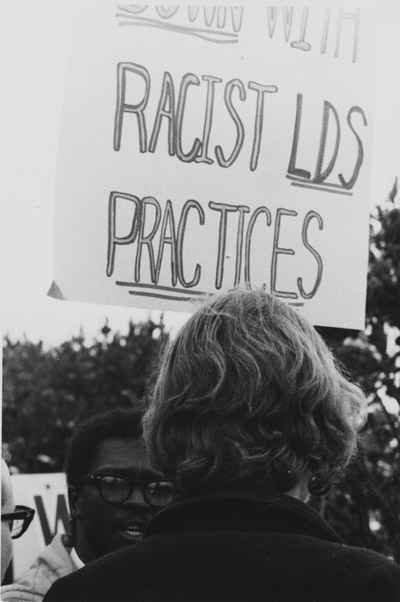

It has been four decades since 14 African-American players were kicked off the University of Wyoming football team after wearing black armbands to a meeting with Coach Lloyd Easton to discuss ways they might protest, during an upcoming game against Brigham Young University, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' ban on African-American followers becoming priests. The incident has since become known as the Black 14.

In the fall of 1993, the University of Wyoming celebrated its centennial football season. Several of the 14 black players returned to campus to recount the events that occurred on that day in 1969. More than 30 interviews were conducted to tell a story of a football program that collided with freedom of speech, freedom of religion and the civil rights of African-Americans.

Transcriber's notes: In most cases I have deleted redundant ands, ers, uhs, buts, false starts, etc. If I deleted an entire phrase, I have inserted ellipses . . . Where you find brackets [] I have added words for explanation or to complete an awkward sentence. Parentheses ( ) are used for incidental non-verbal sounds, like laughter. Words emphasized by the speaker are italicized.

~Transcribed by Russ Sherwin, Sept. 5, 2010, Prescott, Ariz.

Mark Junge: Today is the 25th of September 1993 and my name's Mark Junge, and I'm talking with Dr. Willie Black. What is your position now?

Dr. Black: Mark, I have a Ph.D. in mathematics that I got from the University of Wyoming in 1973, and I'm presently the professor of mathematics at Olive-Harvey College in Chicago, Illinois.

Mark Junge: Okay. We're here in the Field House here at the University of Wyoming, the old basketball field house, looking south onto a nice practice field here, and Dr. Black and I today are going to talk a little bit about the Black 14 incident. Maybe you'd like to describe real briefly what went on today to sort of set the times.

Dr. Black: Today? We went to a football game. Wyoming won! What was it, 28 to 12 or something like that. That was great.

Mark Junge: And you guys—why are you here today?

Dr. Black: Dr. ['Niyi] Coker, who is the African-American Studies chairperson contacted me a few months ago and said he was working on something that had to do with the Black 14, and would I be amenable to cooperating. Of course, I told him I would. I didn't give his ambitions the chance of a snowball in hell at that time, but he continued and he contacted me on subsequent occasions, and it culminated in my coming here this weekend.

Mark Junge: Do you mind talking a little bit about your past, if I ask you a few questions?

Dr. Black: Well, let's try it.

Mark Junge: Okay. First of all, when and where were you born?

Dr. Black: I'm out of Monroe, Louisiana, December 5, 1933.

Mark Junge: So you are 60, nearly.

Dr. Black: Will be.

Mark Junge: Tell me a little about your background, Dr. Black, your youth, where you were raised.

Dr. Black: Town of Monroe, Louisiana, small little black enclave in the city. It's very segregated in the South, and I went to a segregated school, four-room grade school. Two grades in each room so you learned what the next grade was. Graduated and went to the local high school where I went for a year. From then, I left the South, because the trend was, you leave the South and go to something better. Racism was rampant in the South--lynchings were not uncommon--and you go to the North. So I went to Detroit to live with my mom. My dad and mom were separated at the time.

Mark Junge: Who are your parents?

Dr. Black: My father is Willie Black, and my mother is Mary Robinson, maiden name. Mary Black. So they were separated, and I went to live with my mother. I stayed there a year and went to school in Detroit, Northeastern High School. I suffered academically there because instead of giving me what was my right to be an algebra student, they put me in a math class. It bored me to tears, and it set me back pretty much like a year. Shop math, they gave me shop math or something, which would be good if I were going to go in that direction.

So I came to Chicago with my dad, and I went to two high schools. I went to Wendell Phillips High School, again South Side. If you know anything about Chicago, you know it's racially segregated. So I went to Wendell Phillips High School for the eleventh grade and transferred to another high school, Englewood High School, also on the south side of Chicago, also black. But it was beginning to be black. There was still some whites in Englewood. No whites in Phillips, but there was still some whites in Englewood, but there were beginning to be less and less. Still had a white principal, still talked about the classics. For our high school song we did “Student Prince.” [A 1920s Broadway hit operetta] (Laughs) Oh, yeah, we did the whole thing. We were--you know!

Mark Junge: What kind of a student were you?

Dr. Black: I was a B student--C-plus, B.

Mark Junge: What were your ambitions?

Dr. Black: I wanted to be an engineer, actually. When I told my parents, they thought it was somebody that ran a train. I abandoned that when I got to the university. I graduated from Englewood and went to a junior college for a year, and then I went to IIT, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Mark Junge: Now, tell me something. I'm curious--Harry Edwards, I think I mentioned him to you--he wrote the book The Struggle That Must Be--says that he was raised in east St. Louis in the ghetto, in the worst part of the ghetto maybe, and he--I am surprised, the way he describes his life, that he ever made it out of grade school. What were the circumstances in which you were raised? Are we talking a middle class group of people here? Lower class?

Dr. Black: No. My parents were uneducated past—my mom was probably fifth grade, and my dad was happy that he had graduated from eighth grade. And he was sorry that he didn't have more education. Because he wanted to do things like go into electronics, but he didn't know how to do the math that was required. That was the thing that always bothered him. But neither one of my parents were high school graduates.

I had a very strong grandmother, and everybody pushed—I was a smart kid, and everybody pushed smart kids to get an education. Everybody knew you were going to get an education. That was just understood. “Keep on keepin' on, boy.” Get something in your head. And it wasn't just me. All blacks, in that area and probably across the nation, pushed education. If you read some of the old black slaves who were not educated, if you read some of those old black things in North Carolina, South Carolina, those slave narratives, you find out what everybody knows, education doesn't mean intelligence. Those people were intelligent and they understood what needed to be done—that you need to be educated so that you can do things.

So my grandmother raised me, sent me north in my quest for a better life. We were like immigrants in that sense. And we just don't know what to do. We get so angry when we read these stories about the immigrants comin' over and how hard they worked, and we see stories about black people on welfare, you know. Not even—nobody ever says that more whites are on welfare, that never comes up. In fact, I'm sure some people don't believe it. But if you just look at the pool, the available pool of people—

Mark Junge: Well, the stereotype is the black welfare mother with a passel of kids and she represents—

Dr. Black: Yeah, she's also gotta be lookin' like a mammy. She's gotta be big and black and have kids hanging all around and want something free. Yeah. That's the image. Anyway, IIT, engineering, changed to education, teaching, mathematics.

Mark Junge: Why did you do that?

Dr. Black: Well, because I didn't have any feeling for what the engineering—I really didn't get any counseling at that level.

Mark Junge: So the only thing to do with that was to teach it, then?

Dr. Black: Yeah, that's an interesting thing. We were just sort of—we were tolerated at IIT. We took the tests. You had to take a test to get into IIT. When I say we, I mean, I can count the blacks that were there. One of them is a colleague of today. Three of us. On the basis of our tests we were admitted.

So you were admitted. They didn't have to like you. But it hurt us in the sense that we were not just—we weren't plugged into anything. We weren't plugged into any of the social events on campus. There weren't any. And there was no sociability coming out of the professors, you know. But some of that was just general. Some of that was, they were nasty to--they were bastards to everybody! But we couldn't distinguish between that and what was racist, and we didn't have time much to reflect on it. We just tried to do our work, tried to get it done. But there was a lot of cheating. Students, white kids there, were cheating because stuff was hard.

Mark Junge: Where was IIT?

Dr. Black: IIT is in Chicago. It's the Midwestern type of MIT, you know, the Midwestern technological institute. Where you get engineers. So people cheated. But we weren't in the loop of that! We didn't have resources. We couldn't go outside and get somebody that had the answers, that knew the stuff. So we suffered alone, we got C’s when other people got A’s and B’s.

Graduated, bachelor's. Weighed going to work for Internal Revenue or teach. I took the training for revenue officer and was accepted, and that summer before I was supposed to go to work for them, I got the results of my application for teaching. And I fell to teaching. And I've never regretted it. I never regretted that.

Mark Junge: Why did you make that decision?

Dr. Black: Because I've always wanted to tell people what to do in the sense of show people things. I wanted to show off my knowledge. That's what teachers are, you know. We're hams. We like to do that. We don't admit it, but we do. We're performers. And I got a good feeling out of being able to do that. Knowing something that someone else didn't know and helping them to know it.

Mark Junge: What year did you graduate?

Dr. Black: I came out of IIT in '57, and I went to work at Englewood the same year. Englewood High School, in Chicago, where I graduated from some years before.

Mark Junge: How did you feel about going back?

Dr. Black: Oh, great! Look, here I am! I made good! I wasn't that much older than my students, and I see some of them now. One of them is my colleague. He still remembers the D I gave him. A D was a failing grade. Football player. Got a D. Didn't do anything! He said it straightened his life up. So those kind of little stories, those little things help you. And teaching was--I never woke up and not wanted to go to work. In forty years, I've never woke up and not wanted to go to work. That's a luxury, I'm sure. I haven't made a lot of money. You don't make a lot of money in education. I tell my students, look, if you're good, education is a way to go.

So meanwhile, I'm doing all kind of things, like many people at that time. Many of my white colleagues were juggling marriage, teaching, night school maybe, and going to college.

Mark Junge: Working on your master's.

Dr. Black: Working on your master's.

Mark Junge: Which was in engineering or education?

Dr. Black: This was—by now the engineering is out of the question. We're educators, we're teachers. So we graduated from a local teachers college. It was Chicago's Teachers College then, but later became Chicago State University. Got a master's, went home for a visit to Monroe, and on a whim, I picked up the phone, called Grambling. [Grambling State University, Grambling, La.] I said, "Hey, I got a master's degree." He said, "You want to come to work Tuesday?" (Laughs) I said, "Let me check it out. I have to go back and give my resignation." I did. I came to work--this is after I had been teaching for about six, seven years. '59 is when I started working. That must have been when I graduated, '59. So sure enough, I worked at Grambling a year.

Grambling was a revelation. I didn't know hardly any blacks in the Chicago area who had Ph.D.s in mathematics, or anything else too much. They just weren't in my environment. When I hit the campus at Grambling, everybody was “Doctor Somebody.” You would go to a dance, and there would be somebody out there dancing all over the floor, and somebody'd say, "Who is that?" "That's Doctor So and So. He's Dean of this, or he's Dean of that." You go to meetings and people were talking, and they'd be polite to you, but if you didn't have a doctorate you weren't listened to too well. So I said, "I better go back to school!"

Now, in the meantime, I've got four children. We all were in Grambling. We all were there. And they'd never seen Afros at that time. They thought we were really radicals. Grambling State University, Grambling, Louisiana.

Mark Junge: Did you have a 'fro?

Dr. Black: Yeah, well what they'd call a 'fro. To them. Because everybody, all black people cut their hair off. I can give you a whole psychological, whole sociological thing. Black people's hair was "bad," quote. So they chose to cut it really close so it wouldn't be "nappy" unquote. Now it's fashionable because you call it Rasta. They even got wigs now, right? (Laughs) But at that time it was a rejection of yourself, and that persists to this day, and some other things. That's a whole subject there.

Mark Junge: Were you caught up at that time with social issues at all?

Dr. Black: Only about being black. You go—in Reston, the little town next to Grambling—go over there to a doctor, and the lady said, "Just follow us right here,"—my wife—she goes back and there's a whole separate room with black people all crowded together. My wife just turned around with the kids and came right back up in the front. And the lady just threw her stuff down. She was so incensed that she didn't "know her place!" Of course, she was taken care of right away to get her out of there! And that was the kind of thing you notice and stuff.

Mark Junge: Where did you meet your wife?

Dr. Black: She was (inaudible).

Mark Junge: While you were teaching?

Dr. Black: Before. I met her when we were just teenagers, late teens.

Mark Junge: Oh, okay. You've been married how many years then?

Dr. Black: Forty? Let's see: thirty-seven. '56? Thirty-seven.

Mark Junge: And all your kids are grown up?

Dr. Black: Yeah, they are, yes.

Mark Junge: Okay, we got you down at Grambling now, and you're working amongst other Ph.Ds. there--

Dr. Black: Other professional blacks in chemistry, mathematics, you name it, physics. It was a mind blower! I didn't know blacks like that existed! So, you didn't get listened to if you weren't a Ph.D. I said, "Well, why don't I--you know?" I didn't even know I was going to get a master's. I went in to my chairman, who had just got his Ph.D. and come to be, there, the head person. I went to his office, I looked at the board and it had Ph.D. study—University of Montana, University of Wyoming, Texas Tech. I applied to all of 'em. And all of 'em accepted me, so I said, "Well, let's see. I've never been to any of these." These were exotic places as far as I was concerned, coming out of the Midwest. Hmmm! The University of Wyoming was offering much more dineros than either of the other two.

Mark Junge: Why was that?

Dr. Black: Much more dineros at that time? Man, twenty-seven hundred dollars, instead of eighteen hundred or nineteen hundred or something like that. It was about eight hundred dollars more than the others, and I had a family of four--er, six. I had four children; we were a family of six. So I think they had the money and they felt they had to do it, if you can believe it, to encourage people to come to such a remote place. That was the image of the university [of Wyoming] at that time. So that was how I got there. Boy, people always ask. I have to answer that a lot of times. How'd you come way out here? And I'd have to give 'em that story every time. Because it was not a normal place where you saw large numbers of black people. Wasn't but eight people in the state and a couple of Indians, you know!

So, here I was at this big institution, glad to be here. All I got to do is study? Oh, wow! This is made to order! Take classes, professors were nice, you know. And then this other thing. I came in '67, '68 I guess, and I'm here a year and all hell breaks loose. Took me right out of my academic pursuits for over a year. I was just caught up.

Mark Junge: This was the Black 14?

Dr. Black: The Black 14.

Mark Junge: Now, you were chancellor of the Black Student Alliance. Did you start that? Tell me about the organization. Who started it?

Dr. Black: Willie Black, Dwight James, William Johnson—may have been one other person—Johnson's wife. Alberta. We all met at Johnson's house, little one-room apartment. They were childless at that time. And the meeting was in response--I don't know if you heard Dwight' s statement today—that Dwight said it in a way that I'd never thought of saying it before. He said the Black 14 started before the incident. It started with the racism that students were experiencing on campus and one thing and another. I don't know if you heard what I said about it when I got there.

Mark Junge: Yeah, but go ahead. I want this down for posterity.

Dr. Black: Well, when we arrived at the university, we were appalled that black students didn't feel comfortable eating in the main cafeteria. It was just such a cultural shock to 'em, this kind of, "What are you doing here?" You know how people can look at you with their eyes and wish you away. So the black students would go downstairs in some area down there and that's where you'd find 'em. I said, "Oh, my goodness! This is awful!" What I didn't know was happening was the black athletes were experiencing things from coaches and--you know, from going to other schools and that that wasn't very good. And apparently this wasn't just at the University of Wyoming. This, over a period of time, probably was a buildup all over the country, because there was explosions all around the country about the same time. So we had decided an organization should be to address the needs, 'cause there was no campus organization, and black athletes couldn't visit in the dorms, and there was no social place for them. They talk about hanging outside of Crane [Crane Hall, a dormitory on the UW campus] and some of those places 'til they'd get tired and go home. There was just no place for them. There was no social activity they could participate in. So we formed an organization, the Black Student Alliance, with the purpose of having an organization that blacks could feel a part of the university and belong to.

Mark Junge: Could you explain the name again, the situation behind the name?

Dr. Black: Dwight's better at that than me. I remember we wanted it to be called the Black Student Organization. And the Black Student Alliance and the Black Student--something else.

Mark Junge: Union?

Dr. Black: Union. That's what I say—union didn't sound too good in Wyoming! So we settled on Black Student Alliance. They wanted to make the head of it such a great name. I was a chancellor! I say, "Oh, wow! I don't even know what that is, but I guess it's great!" So I became the first—and the group that formed was the members that I just spoke of. And we met, and we went to the university for a charter, and the charter was granted because we raised the point with the members of the Student Activities Board and so on and the hierarchy of the administration that there was really no place for blacks on campus, and that other groups had money, budgets, etc. So they were reasonable, and so they said yeah, okay. So that's how we became the Black Student Alliance. A legitimate organization for the school.

Mark Junge: Did you immediately have a lot of people signing up, joining the organization?

Dr. Black: Oh, it was a significant number. Remember now, there wasn't but about fifty blacks on campus, you know. There may have been a couple that didn't, but most of the blacks on campus could identify with the organization, and they would come because they would do functions, have dances and that.

Mark Junge: So the function then was to get the blacks on campus involved in social events, this wasn't—

Dr. Black: Kinda. That was it. And so they wouldn't be so isolated and feel not a part of the thing. It wasn't to oppose anything at that point. Sure, we wanted to see Jets and things in the bookstore—Jet magazine, a black publication—or black publications being sold and so on, even to the point of having black hair preparations being sold, you know. But those were long-range things. Those weren't immediate objectives.

Mark Junge: What was the perception of you, Willie Black, on campus at the time--getting involved?

Dr. Black: There was no perception. I was a graduate student. I was the oldest one, and the students that were in it elected me because I was sort of an older person. In fact, I was about the oldest. I was 36 when I came here, so I must have been like, 37, and we're talking 26, 23, 19 and 20 year old kids, you know. So that was the inception of the organization, the impetus there.

Mark Junge: Did you get support from the student body student activities organization, from the administration of the college?

Dr. Black: Kid MacMillan. Stu MacMillan? What was his name--Hoke MacMillan was the chairman of the student government, and I thought he was a reasonable youngster, you know. I don't know where he is now. He may be in the management of the government. He may have just become an attorney or something. Whatever. They thought our reasoning was logical. They weren't about to accept us into Chi Omega or anything, and really they weren't askin'. Blacks weren't asking for that. But they were saying, “We need to be a part of the university structure. We don't need to be just disregarded or only on the football team or whatever.” So as far as students, they didn't know me from Adam. They didn't know about the organization. Only those that were participant to the allocation of funds, when it came to that. I didn't become an issue until—

Mark Junge: This was the first black student organization on campus ever at Wyoming, right? Or was it?

Dr. Black: I can't swear to it. I would think it would be, since there were no blacks on campus before that, to speak of.

Mark Junge: Now, were the football players members of the organization?

Dr. Black: They were grandfathered in, sort of. They chose to kinda stay on the periphery and see what was going on. When there were dances they would come, and some of the girls. So they were, in that sense.

Mark Junge: But didn't officially join and sign the rolls.

Dr. Black: There was no signing of the rolls or anything. We just said all black students in the university are in the organization whether they wanted to belong to it or not. Whether they want to do anything actively or not, we're here for them. And that's the way we ran it.

Mark Junge: What happened in 1969? October 16 was the day that this occurred or started. You said it started a little earlier than that. How did you feel coming out here? Granted, there's not that many blacks on campus. Granted there's mainly football players on campus. You were working on a Ph.D. in mathematics. Pretty unusual, right?

Dr. Black: Pretty unusual.

Mark Junge: You must have felt pretty lonely.

Dr. Black: Not really. You don't have time to do too much feeling lonely. You're in classes and you got hard stuff to do, and you go to the library a lot. So it wasn't--I didn't experience any of that. I had a family, remember, so my biggest problem is I'm wearing a bunch of hats. My wife is trying to raise an 8-year-old, a 6-year-old, a 12- and 13-year-old. And they're going to school. So I got my hands full. I'm calling their teachers, and I'm telling the 6-year-old's teacher that I don't want her singing "Little Black Sambo" songs in school. This is how bad it was: "Eeney Meeney Miney Moe. Catch a Sambo by the toe. If he hollers let him go." She's singing that at the dinner table. And I said, "Oh, sweetheart, sing that again." She sang it again. "Where'd you learn that?" She learned it from her teacher. I looked at my wife and I said, "Oh, I gotta go up there and talk to her teacher now." Teacher was amazed that it was a problem. She didn't mean it that way. She didn't mean anything by it. Well, I advised her that it really means something very bad to a black child. Little black daughter of mine was in that class. And I said she shouldn't be doin' that. Something she shouldn't be doing. And you'd have to go up for different things. You got four kids, you gonna have to go up at least four times during their school years.

Mark Junge: How did people treat you here on campus?

Dr. Black: What do you mean, people?

Mark Junge: Just the rest of the student body, your colleagues in the department?

Dr. Black: No problems. I taught classes, graduate students. I was the graduate teaching assistant. Students just look at whoever's up there as the authority and they don't react to it. I didn't get nobody writin'—the FBI is worse, as you found on the recent case by the black guy. They were writin' terrible racial epithets and stuff and leavin' them where he could see 'em. None of that happened. Wasn't that meanness. It was just the kinda--you know, we're not really ready. We don't know anything about black people. I mean I might go into an office and they might look up and see my black face and go on, continue working. I might say, "Is anybody working today, or should I come back when you're open, or what?" Oh! Oh! They didn't mean anything by this, they just used to not regarding people, so it was like we just had to get some elbow room. Say "Here we are! Like it or not." So we weren't walking around seething, or anything.

Mark Junge: Did you have any idea when this whole thing broke loose, how bad it was going to be?

Dr. Black: Nobody! It was like walking into a buzz saw. Nobody could envision, and I'm sure [University of Wyoming Coach] Lloyd Eaton didn't envision that this thing would go longer than a day or two. I'm sure in his experience with players, they would always come crawling back, you know. They want to play ball! And this, after all, was their careers.

Mark Junge: When did your involvement start—can I call you Willie?

Dr. Black: Sure!

Mark Junge: When did involvement in this whole thing start? Can you set the stage so people understand what happened?

Dr. Black: The Black Student Alliance had an office. So I'm sitting in this office on Friday morning, I look up, Ron Hill, Mel Hamilton and Tony McGee said, "We're off the team. Hey, Willie, man—we're off the team!"

I said, "That's too heavy, man. You gotta be kiddin'! Get outta here!"

Says, "No, man. We're off the team. Coach put us off the team!" [I said,]"Put you off the team for what?"

Well, so the start of that was, the preceding meeting I think we met on like a Thursday night or something, and at that meeting, I don't remember when it was, but somewhere along the line I became aware that the Mormon Church [The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints] owned BYU [Brigham Young University], and I also quite accidentally became aware of their policies regarding their black membership. And for those people who don't know, at the time a black could not become a priest; a black man could not become a priest in the Mormon Church. So people, might say, you know—no. What we mean by priest is a 12-year-old. We mean a black 12-year-old. A white 12-year-old gets twelve and it's like the Jewish people have, you know--

Mark Junge: Bar mitzvahs. [Jewish rite of passage celebrating a boy’s 13th birthday]

Dr. Black: Well, they have a similar thing, where the 12-year-old white male is given certain rights. He passes through certain rituals and that and he becomes a priest in the church. Black kids say, well what about--no, I'm sorry. Well, why not? Well, because you're black.

Well. They could dress it up any way they liked. When I discovered that, I said, I just said, that seems like an affront to the human dignity of many blacks. I don't even know why a black would want to be in such an organization--and blacks were members! They've always been in the Mormon church. In fact, they've been in the Mormon Church since the Mormons came west.

Mark Junge: Yeah, you were saying--tell me about that, a little bit.

Dr. Black: I began to read about the Mormons, and in my research it came out that Joseph Smith had started the Mormon church somewhere like around 1831. He'd had a vision and these plates were supposed to be sacred and only he knew about the plates. He, of course, became the first leader of that religion. That was in New York. So they moved from New York to Illinois, a place called Nauvoo. They named the town. In Nauvoo they thrived until the local residents, incensed about their supposed policies of polygamy and all those things, decided to attack them. Now, you know, people do things for a lot of reasons. They might have been doing it to take the people's land, lot of reasons. But that was the effect of it 'cause they ran 'em out of town, and they killed Joseph Smith. They propped him up against a well and used him for target practice. He was lynched in the sense, in the truest sense. So they got their belongings and in handcarts they walked—with their animals and that—from Illinois across the United States until they ended in the Great Salt Lake Valley. This is the story of the Mormon people. I didn't know this. I gained a lot of respect for them as a people, and I sympathize with the assassination of Joseph Smith and all those things. Now I said blacks were with them. At least one black was responsible for accounting for the number of miles they traveled each day. He just counted the revolutions of the tires.

Mark Junge: He devised an odometer of some sort.

Dr. Black: That's my point. Not a lot of people are aware that his rigging of something to count that and tick off things was the first crude odometer in the history of America.

So a 12-year-old black couldn't do that. And we were playin' Brigham Young comin' up. I said, "My goodness!" So I talked to the guys, I told--actually it was a meeting of the organization, at the meeting I said, "You may be aware of this, you may not be aware of it. Brigham Young University is owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And the church has the policy--" and I told 'em what the policy was, and I said, "This seems like an affront and I think they should be protested. They should not be allowed to come up in here and students go out and play in a game like they were just an ordinary 'nother team." And I told the students that the BSA [Black Student Alliance] will protest them coming. But the football players, you have a special situation. You have to go on and make your own peace, which they did. And they voted to protest. But they thought about it, had second thoughts, and thought they should go to the coach and at least afford him the opportunity to sanction it. They felt that surely he would agree with their feelings about this. They put on black armbands [over their street clothes] and they all went to see him together.

Mark Junge: Did you go to that?

Dr. Black: No. In fact, I didn't even know that they did that until they came in that morning and told me. What happened next--almost to a man, if you talk to any of the 14, they will probably tell you what happened. Which, by the way, is not in some of the reports.

They say, or words to this effect: "Coach, we would like the option of sitting this game out, or if we play it, to at least wear black armbands to protest the racist policies of the Mormon religion, of the church. Church's religion." He cut 'em off right at the pass. Invited 'em out into the arena, field house I guess, told 'em sit down and began to tell them they should be glad to be goin' to the university. Or they could go on back home on colored relief, and Negro welfare, and go back to pickin' cotton, and stuff. He said a lot of things that really lasted with these students, because he was their mentor. He was their father image, and they never thought these kinds of things would be forthcoming from him. "You're all off the team!”—and that was when they came to me and told me. And that was the beginning of what has now been termed the Black 14.

Mark Junge: There was no attempt on his part to even find out more? I mean, this was the first time they had gone to him?

Dr. Black: First time, apparently, that they had ever gone to him about anything, and that was his response.

Mark Junge: Now when these three ballplayers, McGee and Hill and--was it Ivie [Moore]?

Dr. Black: Well, I don't think Ivie was one of 'em. He may have been, you know, he could have been one of the ones that came in.

Mark Junge: Mel Hamilton, okay. When those three, maybe more, came to you, what was your reaction? What did you say?

Dr. Black: Just what I told you. I said, "This is crazy!" And I had to try to call around to see what I could find out about it. It hit the campus like wildfire. They were going to have to play games without them, and there were meetings to try to save—'cause they were lookin' down a sure championship that year. The team, these were all starters, for the most part. At least four of 'em were starters. And the team was a good team. But the coach was, you know--

Mark Junge: Did you try to step in at that point and do—what was your reaction?

Dr. Black: No, I don't recall talking to Lloyd Eaton, ever, about the thing. Oh, he made some racist statements about me, callin' me a "field hand." I'd never heard that term.

Mark Junge: He called you a "field hand?"

Dr. Black: Yeah, and "That field hand." He was quoted, I'll say it like that. He may not have said it, but he was quoted as—I'm pretty sure—

Mark Junge: Did he know you?

Dr. Black: No. He didn't know anything about me. But during the period there were people saying things, that I was not a student or not an athlete. In fact a very famous NCAA document came out with that phrase, and the only thing I can surmise is either they were fed the wrong information or intentionally distorted facts.

Mark Junge: What was your reaction after these guys told you this? Was your inclination at that point to just let things lie for a little bit and see what happened? Did you get mad and try to do something?

Dr. Black: Well, no we wanted--I don't remember how we tried to see if this were actually the case, but it was mostly like, is this—is he really going to try to do this? And as time went on it didn't get any better. People began to call us. I probably called somebody, but people began to--Oh, somewhere along the line I wrote that letter that they're talking about.

Mark Junge: Was it a "To whom it may concern" letter, or did you write to the administration?

Dr. Black: Well, it was mailed to the hierarchy of the school. It was mailed to those people.

Mark Junge: Well, were you considered, Willie, were you considered then the spearhead of what went on after that? I mean, in defense of the blacks' rights, civil rights. Did you lash out at the administration? Did you make demands, or did you just—

Dr. Black: No, no. Nothing like that. It was--it came down to--they tried to do something like that, but it was about the Mormon—whether the practices were—they were talking about whether they had a right to their beliefs and stuff. And I said, "Sure they have a right, but you are being cavalier about it 'cause it's not you." People have to do what they have to do. If it don't affect you, naturally you can see where we need not get so bent out of shape, ’cause you want the game to go on. And that's your biggest thing in the school. You must know that these guys want the game to go on, too.

Mark Junge: Well, what was your role, though? Did you--

Dr. Black: Within the organization just try to field calls about things and try to find out--somewhere we realized we had to try to get 'em back on the team, and somewhere we had to get some legal assistance.

Mark Junge: And that's when you went crazy trying to do everything. You were besieged at that time.

Dr. Black: Oh, yeah. There was a lot of things happening at the same time. I was receiving calls from anonymous sources telling me watch what I was doing and all kind of shit. And now, I find out later, you know—freedom of information, you find out some things that a lot of this was disinformation. Things to try to—as if we were really a subversive group, you know. The kind of things that were done to--I'm sure it was just the kind of thing they did to all the groups--people label.

Mark Junge: Oh, sure. Did the FBI have a dossier on you?

Dr. Black: Oh, I'm sure! I would be willing to bet a thousand dollars. I haven't bothered to get mine because I don't think I'm up to readin' it. (Laughs) but I'm sure I was targeted. Harry Edwards, the guys over at—what's that little school over there by Rutgers, where the black students, you know—

Dr. Black: Uh, Cornell [University, in New York, where armed black students occupied a university building for 36 hours in April 1969].

Mark Junge: Cornell, sure. They identified people on campus all over the country. And they proceeded to do that. That's all they did. The FBI has so much money to do that kind of stuff with. Now we find that the—and this is hard for a lot of white people to believe—that the government operates against its citizens. And of course it's easy to characterize us as some kind of subversive things, but we find out they were spying on Martin Luther King and his family for the last seventy years. Seventy!—his forebears.

Mark Junge: Well, let's go back a step, real quick. I'm trying to piece together the roots of this thing. Were you aware of Harry Edwards and what he was doing organizing—

Dr. Black: I'm well read. I knew everything about what people were doing across the country as much as you could read in newspapers. Yeah. And remember, we were just coming out of the '68 Olympics where the black John Carlos and [Tommie] Lee Smith and so on—Evans—held the black fists up, and this was a hell of a statement at that point. And that's it. Make us happy, you know.

Mark Junge: Edwards mentions in his book that—and I might have told you this—but when a black student athlete signed his check in some cases—I don't know what schools in particular he's talking about—but when they signed that check, they weren't allowed to turn that check over because if they turned that check over they lost their scholarships. And the reason why they didn't want 'em turning that check over was because the money was not coming, possibly, from the sources it was supposed to be coming from. In other words, white guys were on full rides, black guys were supposed to be on full rides, but the money for the blacks was coming from federal programs—low-income programs for blacks. It wasn't as much money as for the whites, and the schools were in some cases pocketing the difference between what the feds were sending and what these guys were supposed to be getting. Were you aware of anything like that that was going on?

Dr. Black: No, I had no concept. That's the first I've ever heard of that. I'm not--if it were true, I'm not surprised.

Mark Junge: Well then, what then happened to you during this whole turmoil? Were you looked upon as a leader? Did people come to you?

Dr. Black: Phil White [editor of the Branding Iron, the UW student newspaper, at the time; became an attorney later] began to write about the Black 14. I think he may have been the one to coin the term in the local Branding Iron. The whole university was rent into those for the blacks and those against. There was very little middle ground.

Departments, some people in departments were not on speaking terms and so on. So it was a real, it was probably the most—I'll say divisive, but that's a good word—thing that happened—the most exciting thing, event, in the state over the last fifty years or so. Oh, there was all kinds of rumors about we were Black Panthers, we were outside agitators, we were sent in to disrupt this program because Eaton was a tough coach, a tough nose, and he had been targeted. These were what I was alluding to, this misinformation, disinformation kind of thing.

Mark Junge: So you were supposed to be brought in there specifically to--

Dr. Black: Yeah, neither student nor athlete. And this Willie Black, you know. Lot of press to the effect that people were going to ride down from Buffalo or somewhere like that and really run me out of town. I never really reacted to that too much because it was so much talk. But they spread the word.

Producer Sue Castaneda: We hope you 've enjoyed this oral history presentation of Dr. Willie Black and will continue on to part two.

[Editors’ note: Part 1 of the audio of the Willie Black interview ends and Part 2 begins here.]

Producer Sue Castaneda: Welcome to part two of this oral history presentation of Dr. Willie Black, a former University of Wyoming football player and member of the Black Fourteen. [Editor’s note: Willie Black was in fact chancellor of the UW Black Student Alliance at the time of the Black 14 incident, but he was not a football player or member of the Black 14.]

Mark Junge: Okay. What did happen in your department? Did people just ignore it?

Dr. Black: They took sides, unbeknownst to me. Some would come up to me and say what they felt, and others, if they didn't agree with me, said nothing to me. One professor asked me at some point, "What do you want a Ph.D. for?" I wasn't doing too well in his class. And my reaction was, "What do you think? Same reason you want one." And my response to him was, in very low key, "I probably want one for the very same reason you wanted one. It's a challenge. I want to see how much mathematics I can learn." He said, "Oh, you're just trying to make me angry." Oh well. I just shrugged my shoulders and sat there. I eventually dropped the class or something. It wasn't one that I needed. Now, that was him.

Mark Junge: You didn't encounter any difficulties with the university administration itself, the big guys?

Dr. Black: No, they all wanted to resolve the issue. The university wanted to resolve the issue, but they didn't want to offend the coach. They didn't want to go against the coach. Carlson, the president of the university—

Mark Junge: He was the most—not Carlson, but Coach Eaton—was, according to [historian T.A.] Larson, the UPI “Man of the Year,” Wyoming “Man of the Year.” He was the most popular man in the state.

Dr. Black: You were going up against a big entity, especially in a football state. So he wouldn't do it. Carlson—my feelings of Carlson was he was a hand-wringer, not a really strong kind of person. He didn't want to rock any boats. So the trustees voted to uphold the coach's dismissal of the players. Well, if the players are not on the team, then the team's got to play without 'em. And all this is goin' on and so on, and the guys are, some of 'em are thinkin' well, we better get out of Dodge and one thing and another. And a lot of 'em left. Most of 'em left. But as you saw in the document by Larson that the university in behind-the-scenes discussions for whatever reason voted that each of these students should have a right to scholarships to finish their education, if they chose to take it. Well, there may be some restrictions, but that was--the university did stand by that.

Mark Junge: Did anybody take advantage of that?

Dr. Black: Mel Hamilton came back and finished his degree. Dwight was not a member of the Fourteen proper, and I don't know if he was grandfathered in on it, but he went on and got a law degree. But I don't think the others—they all scattered to the four winds.

Mark Junge: But there was a statement made this morning at the Washakie Hall [on the UW campus] where they had all these little speeches--something about Coach Eaton saying that you guys would never amount to a hill of beans? Something like that?

Dr. Black: Said it to them. There was some hurtful things said by the coach. I had never thought about saying anything about him, and I never really did. I think my only response was that these 14 young men have their lives ahead of them and his is behind him. That's about all I said.

Mark Junge: And these 14 young men did. What did they go on to accomplish?

Dr. Black: Well some of 'em did things that would be interesting. Tony McGee went on and played for the Bears and New England. He was probably the only one, I think, that went to the NFL. Maybe there was one or two others tried out somewhere. I know that Ivie went--no, Ron Hill--went to Howard University, a black college. Mel Hamilton said the most [important] thing that he learned from all this--Mel has a master's degree now—was that he could study and know stuff other than football. He said that the impression that he got from being around the football program was that you really can't do anything else. So he said that twenty years later he's finding out that he's as smart as anybody and can do any—if you ever hear him speak, he's very eloquent.

Mark Junge: This morning, Coach Eaton got up, and the provost--I can't remember his name--

Dr. Black: I don't think Eaton was there.

Mark Junge: Excuse me! Coach Roach, Athletic Director [Paul] Roach. In effect, what they were saying was that we're glad to have you guys back. We've made some progress here. We've got more black students, more minority people doing this and that, and I got the impression that the statement was being made to the Black 14, anybody who was associated with it, that things are better. Are they?

Dr. Black: Well, you're not asking the right person. I've always felt that the university had a—wanted to do more than it ever did. I've always had the feeling that they wanted to do things. They brought Barry Beckerman here, a black professor of English, came in here. He'd written a book and so on. They brought another black professor in after that, John Wideman, who's well published. They seemed to have always had a desire to do something more than what they'd done. And even now they're bringing in people. So I think they're making an effort to—what did they say? To have a visual cultural diversity? And I think that can be nothing but good! In most places around the country, you find that goin' the opposite direction. I mean the big universities. A lot of racism on big campuses.

Mark Junge: Yeah, what's happening? I don't understand this in America. I don't understand this going back.

Dr. Black: Well, we got a lot of things going on right about now. You've been reading about the X-generation and the busters and boomers and that. And there's a lot of discontent around the country. We got a—the country's economy is falling apart. There are people that have degrees now again—every twenty years it looks a cycle or something, huh? In '73 people were trying to get jobs as cab drivers in

Laramie [Wyo.] who had degrees, Ph.Ds. and master's and so on. And it's that way again now. With the downsizing, every day--every day--you read, fifteen hundred, four thousand, thirty-one hundred. Well, how can this go on? These people are never re-hired! So you have, now, kids back at home, some of them are back at home before their brothers and sisters get out, who've been out there, got a degree, and worked and got laid off. So now they're home doin' what they call “Mac Jobs.” They call 'em “Mac Jobs.” “Mac Jobs” are flippin' burgers. McDonald’s type things.

Mark Junge: Willie, looking back on this incident, how do you feel? How did you feel coming back?

Dr. Black: Mixed emotions. I feel that we made a contribution that we had to make. The university was enriched by us having been here, and they continue being enriched by the cultural diversity that they're encouraging at this point. It doesn't have to be that people can't communicate. It doesn't have to be that way. In America there's enough to go around. But it's never been told to the American people, it's so easy to say, well, you know, those welfare recipients over there, those people over there are the reason you don't have yours. And that's what I was getting at. These Generation X people in their 30s and stuff, you know, they're mad! They're lookin' at the age group that's ten or fifteen years older than them, and they're the enemy now, because they're suckin' up--they have the good jobs, they're makin' sixty, seventy, eighty, hundred thousand a year, and they're not movin' out of the way! So there's [a] lot bein' written about it, by the way. Read, if you're interested—

Mark Junge: But you said you felt ambivalent about this.

Dr. Black: Well, I felt that I wish I could have made the omelet without breakin' eggs, so to speak.

Mark Junge: Really?!

Dr. Black: Well, sure. You wish--if you're a commander of troops, you don't want to lose troops!

Mark Junge: No, but you couldn't have made progress. I feel about this whole incident—'cause I have it in me, a feeling in me, that there should be this reconciliation as well. But I don't think you can make progress in a state like Wyoming, or in a country like we're in, I don't think you can make progress without breaking eggs.

Dr. Black: Well, that may be true. I'm just telling you the feeling that--oh, I wish that these kids could have all had their shot at the NFL, just naturally so, as a result of having been at the university and been scouted and all that. And they were robbed of that. I just wished that there was something that I could have done to prevent that. I've done that with my kids. I never want to make a decision involving my kids that they could come back later and say, "Well if you'd let me do it my way--" The only thing I've told them is that as long as they were under our roof and so on, that they would have to do things a certain way, but when they got out from under our roof, then anything that they come up with—

Mark Junge: So do you feel guilty?

Dr. Black: Well, it's not guilt. It's just that you don't know if you really understood totally. It gladdened my heart to hear the guys say everything, except they blamed me for what happened to 'em. Now maybe they do, maybe they don't. I don't think they do. But to hear them say they felt they're better men for it, and that they can deal with some diversities in their lives--

Mark Junge: Because they had to make a commitment at that time.

Dr. Black: Well, they don't know what it's like not to stand up. There are people who live their whole lives and never stand up. There are people who live the safe life all their lives, and it don't mean they don't get kicked around, but there are people that--you probably know 'em!

Mark Junge: I was one of 'em!

Dr. Black: --that will stand for anything! They do that.

Mark Junge: No, I admire them. So you can take some consolation in the fact that here are some guys who are coming back to you today and saying, "Hey! My life took a different course, but I'm happy."

Dr. Black: Yeah. And that they've done something with the--that's why I used the analogy about the hand that you're dealt. Playin' it instead of cashing in. And they played it, you know.

Mark Junge: Well, you are--I sensed you got a little emotional there at the very end when you talked about the Fourteen.

Dr. Black: Yeah, I love 'em! All of 'em. There were a couple of quote, turncoats. And I know the pressures they were under. There were some hints that they maybe were solicited by those forces that I alluded to earlier to say things that were just not accurate. "We were coerced." You heard what they said. I never coerced anybody to do anything or brainwashed anybody to do anything.

Mark Junge: Do you feel like you made a part of history?

Dr. Black: Oh, no doubt about that. When you tell me right away that there's two theses in the library, or that here he's writing about it. [Historian Clifford A.] Bullock got his [University of Wyoming] master's the other day. He had called me at home, so there's no question about it. Those black men--and they're history, 'cause I wrote like I said, in the flyleaf of my thesis, I dedicated it to them. Among others. I dedicated it to my family and to fourteen young black men.

Mark Junge: Your thesis?

Dr. Black: Yeah. You go can up to the university, see my thesis. Ph.D. thesis.

Mark Junge: Why did you come back out here?

Dr. Black: When?

Mark Junge: For this.

Dr. Black: For this? Well, that's the answer! For this! I came back out to—[UW African-American Studies Chair 'Niyi] Coker made such a--he said, "We're walking the paths--" He's a very convincing person--"We're walking the paths that you've provided!" So I said, "Okay, Dr. Coker, I will come."

Mark Junge: Are you glad he did it?

Dr. Black: Oh, I'm elated that these young men are given some recognition for standing up. 'Cause nobody gives you recognition for that. You just take your licks when you stand up. And you wonder, if you prepare people for if you want to be free or whatever, is you have to prepare the troops for what's going to happen, you know? I don't know if you did that, I don't know if you do that, I don't even know if you knew that.

I was just thinkin': At twenty-seven, Castro had taken his country back from Batista. His cards were different. He was in a different place. These young men, that was their Cuba. That was their--in other groups, that's what I want to communicate to those younger ones. Their Cubas will be different things. They will have their--as they live long enough they will be called upon to make a stand, and they have to know that when you do that, there are people all over this country who have made stands, lost jobs, not that they wanted to lose jobs, but because something was so--something that they felt so strongly about made them act in a certain way, and they didn't weigh or care about the consequences.

Mark Junge: Well, wouldn't it be nice if those people who made that sacrifice could come back and see that things have changed?

Dr. Black: Oh, yeah, no question about that. That their thing was not in vain. Yeah. No question about it.

Mark Junge: And I don't know that they can say that.

Dr. Black: Well, the ones that didn't come can't, but the ones who did can say, "Well, there's some evidence, some visual evidence." You didn't have even a discussion of black administrative people anywhere in the hierarchy of the administration. Sure, you got a band leader or something, but you didn't even have that. So it's slow. I think they're kind of--like I say, I think the university has always wanted to do more than they had. And it wasn't a monolith. It wasn't like fighting against the whole thing.

Mark Junge: No, but your struggle, nevertheless, was with the school. It wasn't with the Mormon Church, it was with the school.

Dr. Black: Oh, it was with the Mormon Church, but the school walked in and interposed themselves. Initially that was the genesis, but the school came in and said, "We're going to take these kids' scholarships." And then our thing had to be a legal thing with them: “Can you do that? You can't do that,” and so on.

Mark Junge: Yeah, that's what the legal thing was all about. Well, I'm just real happy to be talking to you about this. Have you done any other interviews with anybody else?

Dr. Black: Nobody's going to put their book out before you! (Laughs) You better write fast, though.

Mark Junge: Well, listen: I want to say how much I appreciate your doin' this.

Dr. Black: Well, it's my pleasure, and as I say, I hope some good comes of it.

Mark Junge: Well, I hope so, too. I mean, this state is a tough nut to crack. And it's not just the state, it's America. I understand, a little bit I understand, anyway. And if you can make a little bit of headway by at least educating people, you know, and you educate people when you come back, and you do this. I'm surprised--this was

Coker's, at Coker's insistence that this thing happened, and I'm surprised in a way that the university didn't take it on themselves to do it, because they have brought in all these other old-timers from long-time back, and I looked at this little article in the paper, and I said, “Wait a minute! This makes sense.”

Dr. Black: I know. It's worse than that. They had the thing last night over at--oh, they had a banquet last night, and apparently [Black 14 member] Ron Hill and a few--I think they probably had all of the 14’s s names out on something. Or maybe only the ones they got confirmed, so they came and I was with 'em, and they had name tags, and they sat and a few black males who knew some people sort of circulated, but the ones who didn't just sat. [Black 14 member] Lionel [Grimes], you know, his wife and so on. If they were introduced, I was introduced, or you were introduced, and you weren't even there. So I don't think this was pointed. I don't think this was-- it's just ignorant oversight. The kind of thing that happens when you have to say, “Hey, look. I'm over here.” And we just shook our heads, you know. All these guys were there, and they were introducing all these people who were in the past, and so here's Ron, er, Mel was on the team in 1966. You know, Mel had two football careers. He came early on, went to the [U.S] Army or something, came back to play football. So he was with the Fourteen, but he had been with the team that went 10 and 1, and was he introduced? (Laughs) He wasn't introduced! Ron wasn't introduced. Ivie, nobody! So you know—

Mark Junge: Well, every black person I've ever talked to about these kinds of matters, and I've asked them, I've said, "Do you think things will change in your lifetime?" And not a single one has said yes.

Dr. Black: Well—well, yes, they will change! I used to think that. I don't have that pessimistic a view. Things will change. But struggle is perennial. That's what you have to understand. If you're white in America, you might think you don't have a struggle, but you do! Because more and more--especially if you carry it as something of an unwarranted right. You find the hegemony of being white is less and less and less and less. So that can't make you sleep well, if you're that kind. All over the world there's discord. So I look at it from that point of view that people are fighting for some kind of expression all over the world, and why should you be exempt? Even if you're white you're trying to get the quails taken care of, you're tryin' to get the toxic waste dumps out of your back yard, you know.

Mark Junge: When I see that my father lived through the Depression by working three jobs when he was going to electrical school in Chicago: at Coyne Electrical, he worked at Harvey's, he worked at the boarding house where he helped the lady make little repairs, and then he—what else did he work? He fried fish at Harvey's, he worked at the boarding house--oh! And then, he went down at the vegetable market in the morning—

Dr. Black: What you're tellin' me is lots of reasons you should be happy about your dad, but also you're tellin' me that he couldn't have been much of a dad, because he was always gone. But the quality time, I guess, when he was home—

Mark Junge: Well, what I'm saying is this: He had to work three jobs to stay alive. I didn't have to do that when I was growing up, and when we got out of the university, not this university, but I had practically things waiting for me.

Dr. Black: That's what my point was about Generation X. They don't even want to finish school now anymore because they don't get the jobs, and if they get 'em, they are only one-year appointments, and they got to run around and do all these things. Some of 'em, if they're in education, are teaching part-time at three and four schools, running around picking up these little two-bit checks, and all of it comes to twenty thousand dollars a year, maybe. And he's rooming' with some lady--he don't want to go home, so he's got his little girlfriend and she's flippin' the burgers, and together they may make thirty thousand dollars if they're lucky.

Mark Junge: And see, it's like they say. Rags to riches to rags in three generations. My father had to work hard. My two boys have both graduated. One graduated from Boston University, one graduated from Colorado College, a nice private liberal arts school, and they're both struggling just to stay employed. So when you say, well you know, the white guy has--you sort of indicate that we've inherited this hegemony, we don't have it anymore.

Dr. Black: It's a struggle. And it has to do, and you'll never get at it because you'll never want to accept—if you accept the Marxist view—and I'm not a Marxist, but I accept the view—that the haves against the have-nots have always run it, but they've been lucky enough to give white people a little bit—enough more than other people so they were happy, but never enough so that they want to really challenge all this wealth, unwarranted, that these people have. These people have unseemly wealth, the ones who are wealthy.

Mark Junge: And see, what Harry Edwards was saying back in '70 or '80 when he wrote this book, he was saying it was doubly frustrating for a black man or a black person in this society because now the economy is turning down and there's white folks suffering, but the black man gets pushed even further down.

Dr. Black: Well, not really—yes true, he's right, but the black people have been unemployed since the first wave! That first wave got us! Now the cuts are getting deep. Every day when you read Xerox or Bank of America is laying off these people, these are white people almost entirely now. They're middle managers, they've been makin' fifty, sixty thousand, now you makin' zero.

Mark Junge: And they're laying them off so they don't have to pay them benefits or retirement.

Dr. Black: That whole thing. So here comes a president, sounds pretty good, I don't know if he's going to give you health and so on. I was in Cuba this summer and I was quite impressed with the HEW of that little small island country. The Health, the Education and the Welfare. There's only like 14,000 people down there, but they're bearing' the brunt of the American people now, unwarranted now, because we made friends with the Faba and we're still trying to punish--you know, and it's really unseemly. And there are people now writing articles about why we doin' this? Why don't we just—but you mention the name Castro, Americans go all kinds of things.

Mark Junge: My sister was over there and she says they're not getting the right kind of press.

Dr. Black: Oh, they're not. Everything you read is negative. I'll tell you this: your next heart operation, go to Cuba. If you have to have another one, go to Cuba. Or if you have to have a transplant of any kind, go to Cuba. Everybody in medicine knows about the excellence of Cuban medicine.

Mark Junge: We're afraid of federal medicine here.

Dr. Black: Listen. There are experts in transplants of all kinds. Experts in penile implants, restructuring and all that. Do you know what the children of Chernobyl are? Well you never thought about the children of Chernobyl. When Chernobyl happened, there were women who were pregnant. Their children came out bleached, albinoed. They're in Cuba. And so the Cuban doctors—you know, Cubans are all colors. They're not just like the ones you see in Miami—sound machine girls and all them. They're not all white. But most of 'em are colored. Some dark like me, and there's racism. Not that you could equate with American racism. None of that, 'cause they didn't have that history. But there's another subtle thing operating, you know. For example, a doctor. There was a black guy, you know—

Mark Junge: Almost like a tribal thing.

Dr. Black: Yeah, something like that. But they've come up with a process whereby they can restore the melanin with no side effects. Oh, it's a fantastic thing. I was just impressed with the —

Mark Junge: Why were you there?

Dr. Black: Because I wanted to go there. Nobody can tell me where I can't go!

Mark Junge: No, but I just wondered what caused you to go there.

Dr. Black: Oh, legitimately, it is illegal to go to Cuba. But there are categories that can go. I'm not answering your question. I'm informing you now. There are four or five, maybe seven, categories. One of them is if you got relatives. Another one is if you're an educator. News media. I happen to be that, too. But I didn't go under that. I went under the educator. Guy at my school was running a tour. They have planes that come out of Miami every day. Every day. But you can't go there and buy a ticket, because you'll be violating the American government. People go. You know what they do, they go to Mexico, Canada and they come in the back door. That's illegal to do, because you're not supposed to spend money in Cuba—Americans. We got an embargo against this little island country and it's been very effective in just crushing them. With the fall of the Soviet Empire, it was even worse.

Mark Junge: Wasn't Clinton trying to make some subtle overtures?

Dr. Black: Not voice, but it's happening. He's saying one thing, but it's happening. But you see all these machinations are just interesting to me. I wanted to see that experiment. I wanted to see a country that tried to disperse its resources to the people. Now you know what you get when you say that in America? Yeah, we'll all be poor. They don't know how wealthy their country is. People that say that don't have any idea how wealthy America is. You would not be poor. You would think if you divided it all, we would all have two dollars, you know. Not so.

Mark Junge: But they scare you with that.

Dr. Black: They scare you with that so you don't even think that. These people have estates way up in places. You make five hundred, how can people make five hundred thousand dollars, a million a year? Two million a year? Lee Iacocca? How much did he make? How can people do that? And where do they live? They don't shop at Kmart or Safeway. You don't see 'em, and they don't want you to see 'em, because you see what they did to the guy when they caught him. They put him in a hole and stuff, you know, the big magnate, owner of something. Remember that guy?

Mark Junge: Oh, the guy they kidnapped.

Dr. Black: Yeah, so they want to keep a low profile, for good reasons. You can't have wealth juxtaposed with poverty. You can't do that!

Mark Junge: You're really an educator, you know. And I appreciate that. You must be pretty eloquent for your students.

Dr. Black: I try to be a role model. I try to give them something. For example, if you and I go into a classroom, we're going to both teach the class, but I'm going to give them something else if they're black students. If you're a white student, I'm just going to teach the class, I've taught at white institutions and stuff. Part time at DePaul with no benefits. DePaul University in Chicago.

Mark Junge: Where you teaching now?

Dr. Black: I'm at Olive-Harvey College. I said that at the first of the tape.

Mark Junge: That's right.

Dr. Black: It's a community college.

Mark Junge: Are you a professor?

Dr. Black: Yeah.

Mark Junge: How long you been there?

Dr. Black: From '74. That's nineteen years.

Mark Junge: So you've got another five years before you retire?

Dr. Black: 'Bout that. 'Bout hittin' it right on the thing.

Mark Junge: What are you going to do?

Dr. Black: I don't know. I don't know. On the one hand you want to say, “Well, I'll go where the money exchange rate's the greatest,” but then a lot of times that place is the worst quality-of-life place. I'll say the stats show that I'm going to be in Chicago. Eighty percent of the people who retire stay in wherever they are.

Mark Junge: Do you like Chicago?

Dr. Black: Not really. There's some nice places. There's some nice things, but I suffer when people suffer and people are suffering. The inner city people. Nobody has ever addressed in all — so that's another book. All civil rights struggles, nobody's ever addressed really poor. Jesse did some things and so on, and that, but the urban poor are problems that have never been addressed. So now it's overflowing. They're shooting each other and now we're finally shooting white people in Miami. The foreigners.

Mark Junge: Are you on the South Side?

Dr. Black: I'm in the suburbs. Southern suburbs. Quality of life's fine, there. Middle class, the whole thing. But I was more middle class in Laramie. Well, think about it. We talk quality of life.

Mark Junge: Yeah, I guess so.

Dr. Black: I lived in married student housing, I made thirty-five hundred dollars a year for four people, and my children went swimming every day. They had safety. They could walk where they had to go. They could ride their bikes. They could go up and play tennis, learn to play tennis. They did. They could go skiing in the winter for no money hardly. Happy Jack [cross-country ski trails, east of Laramie], you know.

Mark Junge: But you wouldn't choose to come back here?

Dr. Black: No, my wife doesn't like Wyoming. She's too cold. She doesn't like it. I wouldn't mind, but it's not in the cards for us.

Mark Junge: What do you call that hat? That cap?

Dr. Black: It's called by blacks, who think it's an African cap, it's called a Kofi, and it's a sort of a chieftain kind of thing. It actually is a Palestinian cap that came from Israel.

Mark Junge: Came from Israel, huh? That's nice!

Dr. Black: It was made by a Palestinian in the occupied territory.

Mark Junge: Isn't that amazing what's happened over there?

Dr. Black: That's what I meant. I don't think we're the only people in the world that have struggles. The Irish and the Catholics, there's no reason for that to be going on except for historical. And they just say, I ain't going to let you—I'm going to keep my foot on you and I've got the army with me, so I can continue. And that' what's happening. So they say when they blow up stuff that the queen is poof! Poof! Poof!

Mark Junge: Yeah, well they're doing it in Bosnia-Herzegovina too.

Dr. Black: That's another can of worms, isn't it? It doesn't give you much hope for the human condition, does it? That we can live next door four hundred years, but if I have a deep-seated animosity toward you, when I think I can get away with it, then I'll jump up and take your house and hold you at gunpoint. And that's what they're doing.

Mark Junge: Well, that's why this Black Fourteen and all these little incidents--Little!--that took place in the Civil Rights Movement are all so very important because, just like case law, British case law based on Roman case law, and ours based on the British. It takes time for this stuff to build up. It takes time. And I see a backsliding, and I think somebody mentioned that, maybe it was you this morning, but I see a real reversal here that's not a good sign. And I think it has a lot to do with the economy, but I don't think it's good.

Dr. Black: You mean country-wide.

Mark Junge: Oh, yeah! In the nation.

Dr. Black: Here's this little island is tryin' to do something another way. They're out of it. They don't know what's going on.

Mark Junge: I know! I gotta tell you. My wife and I went to California to visit my son in San Francisco, and from Reno down the Interstate, down I-80 to San Francisco, it's all urbanity. I mean, it's all--

Dr. Black: It's a long city. It's a big city.

Mark Junge: It is. We are in an island. I don't think the people here realize that we're on an island.

Dr. Black: It's an island in a lot of ways.

Producer Sue Castaneda: A one-hour documentary DVD was produced by the University of Wyoming Television Department containing a number of other interviews of individuals involved in the Black Fourteen. See the appendix at the end of this document for details.

Conclusion of interview

We hope you 've enjoyed this oral history presentation of Dr. Willie Black. He is interviewed by Wyoming oral historian Mark Junge This podcast is produced by Sue Castaneda for the Wyoming State Archives, the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. Be sure to listen to other Wyoming oral history podcasts on wyoarchive.org and the intemetarchive.org.

Resources

- White, Phil. “The Black 14: Race, Politics, Religion and Wyoming Football.” WyoHistory.org, accessed Oct. 23, 2013 at /essays/black-14-race-politics-religion-and-wyo.... The article includes more photos and an extensive bibliography.

- McElreath, Michael. The Black 14. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming Television, 1997. Documentary on DVD.

Illustrations

- The photo of Willie Black at War Memorial Stadium when he visited the University of Wyoming campus in 1993 is by Mark Junge, Wyoming State Archives.

- The photo of Black at a 1969 protest on the UW campus is from the Branding Iron Collection at the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Author

- Dr. Willie Black, who was chancellor of the Black Student Alliance at the University of Wyoming in 1969, was interviewed by Wyoming Oral Historian Mark Junge in 1993. This podcast is produced by Sue Castaneda for the Wyoming State Archives, the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. Used by WyoHistory.org with permission and thanks.