- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Wyoming Troops In The Philippines, 1898

Wyoming Troops in the Philippines, 1898

When the new year of 1898 began, President William McKinley was unable even to locate the Philippine Islands within 2,000 miles on a world map. One prominent American observed that the people of the United States did not know whether the Philippines were islands or canned goods.

All of that changed on the morning on May 1, 1898, when U.S. Navy Commodore George Dewey led his fleet into Manila Harbor and destroyed the Spanish fleet that had been defending the island colony. But though Dewey won one of the most lopsided victories in American naval history and Spain soon ceded the Philippines to the United States, it would be nearly four years before the colony came fully under American control.

Cuba, which had been a Spanish colony for centuries, had begun to experience an increasingly determined insurgency aimed at achieving independence. American support for the Cuban War of Independence, and Spanish antagonism, fueled by media interest in fomenting a great conflict that could be reported by William Randolph Hearst’s scores of newspapers, generated increasing tensions between Spain and the United States.

The U.S. Government dispatched the battleship U.S.S. Maine to Manila harbor to protect U.S. interests in January 1898. On February 15th the Maine exploded, killing 260 sailors. Although the reason for this explosion has, to this day, never been satisfactorily explained, headlines of “The Yellow Press” screamed “Remember the Maine!” Spain severed diplomatic relations with the United States on April 21, 1898 and the U.S. Navy quickly blockaded Cuba. Four days later Congress declared war on Spain.

On April 23, President McKinley issued a call for 125,000 volunteers to serve in war. Wyoming provided approximately 1,000 of those volunteers. These included seven troops of cavalry to the 2nd U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, known as “Torrey’s Rough Riders” for their commanding officer, Col. Jay L. Torrey, a prominent rancher and member of the Wyoming Legislature from Fremont County. A companion regiment to the more famous “Rough Riders” or 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment raised by Col. Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, Torrey’s Rough Riders never saw action during the conflict.

Stationed in an Army camp in Florida, their single greatest loss of life occurred in a train accident near Tupelo, Miss., when five soldiers—all from Wyoming—were killed while enroute to Florida. In addition, thirty men died of typhoid fever at their squalid Florida camp.

Wyoming’s most significant contribution to the Spanish-American War was one battalion of infantry, consisting of four companies, augmented by a battery of artillery. The 1st Wyoming Infantry Battalion’s four companies were: Company C from Buffalo; Company F from Douglas; Company G from Sheridan; and Company H from Evanston. Maj. Frank M. Foote, a state of Wyoming financial manager from Evanston, commanded the battalion. The unit’s strength at muster-in at Cheyenne was 14 officers and 324 enlisted men. Capt. Granville R. Palmer commanded an additional light artillery unit, Battery A, from Cheyenne.

Wyoming’s most significant contribution to the Spanish-American War was one battalion of infantry, consisting of four companies, augmented by a battery of artillery. The 1st Wyoming Infantry Battalion’s four companies were: Company C from Buffalo; Company F from Douglas; Company G from Sheridan; and Company H from Evanston. Maj. Frank M. Foote, a state of Wyoming financial manager from Evanston, commanded the battalion. The unit’s strength at muster-in at Cheyenne was 14 officers and 324 enlisted men. Capt. Granville R. Palmer commanded an additional light artillery unit, Battery A, from Cheyenne.

The Wyoming battalion left Cheyenne on May 18, 1898, and traveled by train to San Francisco where the troops spent six weeks training and drilling at Camp Merritt at the Bay District Racetrack. On June 27, part of what was officially designated as the 3rd Philippine Expedition, the battalion boarded the troopship Ohio and crossed the Pacific to the Philippines, stopping in Honolulu en route.

On arriving in Manila Harbor, they were assigned to the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, VIII Army Corps—part of a force of 11,000 American ground troops, both U.S. Army regulars and volunteers, in the Philippines. On Aug. 13 they began participating in operations intended to seize the city of Manila from the Spanish, and hold it. Following behind the 1st Idaho Volunteer Infantry Regiment and the 18th U.S. Infantry Regiment, the Wyoming troops were never engaged in the action. The men occupied a Spanish barracks inside the city. They raised the U.S. flag over Luneta Barracks, previously occupied by the 73rd Regiment of Spanish Infantry, at 5:30 p.m., Aug. 13.

The 1st Wyoming Battalion served as a portion of the garrison of Manila through February 1899, with the group’s principal events being the organization of a regimental band and baseball team, Thanksgiving, Christmas celebrations—although they didn’t receive Christmas packages until early March—and New Year’s Day.

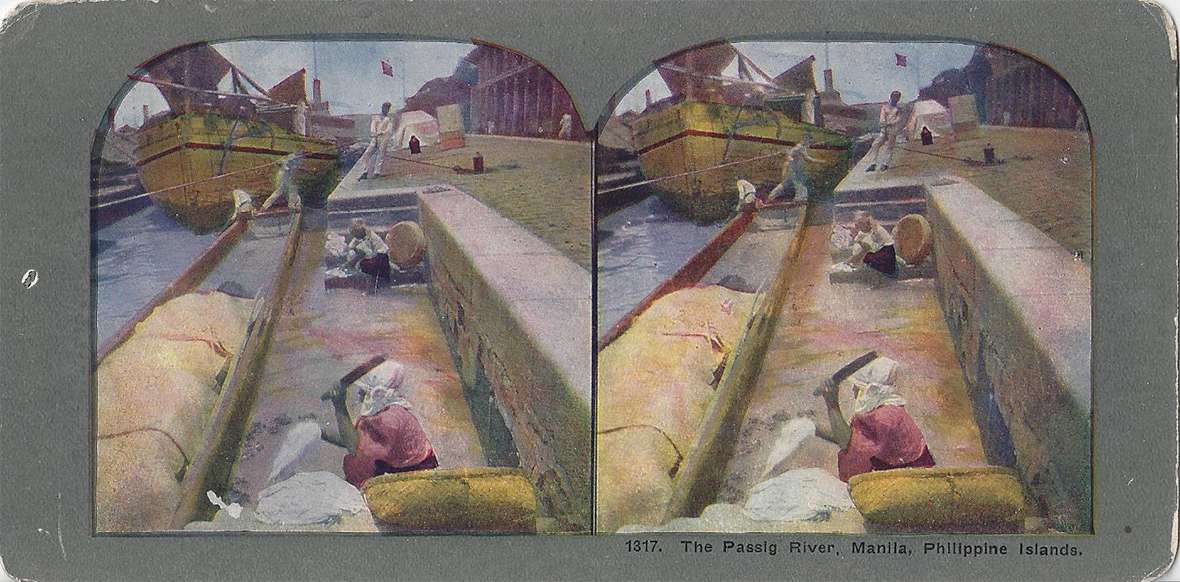

In early February, the battalion received orders to join in dilatory guard duty, patrols and counterinsurgency, with occasional vicious skirmishes and battles, against Filipino insurgents. On Feb. 5 they advanced along the Pasig River to the hamlet of San Pedro Macati. Advancing against insurgent forces occupying the churchyard, Sgt. George Rogers and Pvt. Ray F. Weidmer of Company C were both mortally wounded. The battalion encountered some brief, heavy fighting while defending San Filipe Church against an insurgent attack during a heavy rainstorm on Feb.22, without sustaining any loss. On March 7, the battalion participated in an attack against the small town of San Juan Del Monte. This time, Pvt. Joseph M. Spaeth of Company C was killed.

The 1st Wyoming Battalion performed intensive counterinsurgency patrols throughout the months of March, April, May and June 1899 without particular incident. The men returned to the Manila garrison to conclude their service in July.

On July 29, 1899, the battalion boarded the troopship Grant for the journey home. They were mustered out at the Presidio in San Francisco on Sept. 23, and promptly returned to Cheyenne for welcome-home festivities. During its term of service, the 1st Wyoming Battalion lost a total of 90 men: Three were killed in action, 12 died of disease, and another 75 men were discharged due to disabling wounds, illnesses and injuries. As with the remainder of the U.S. Army during the Spanish American War, many more soldiers from Wyoming died of disease and illness caused by poor sanitation and diet and inadequate medical care, and from numerous tropical diseases, than were ever felled by a foe’s bullet.

Simultaneously, Wyoming’s Battery A, the light artillery unit, underwent various trials. Initially understrength, several additional members had to be recruited to bring the unit up to required numbers of three officers and 122 men in Cheyenne before the group could be accepted into federal service. Following the swift last-minute recruiting effort, they mustered in at Cheyenne on June 16, 1898, and spent several months in San Francisco training, undergoing drill, fostering discipline, and being adequately uniformed and equipped before leaving for the Philippines.

Under the command of Capt. Harry A. Clarke, the battery sailed from San Fancisco on Nov. 8, 1898. They had embarked without their original commanding officer, Capt. Grenville Palmer of Cheyenne. Unfortunately, Palmer had suffered a mental breakdown. He committed suicide at the Presidio in San Francisco on Nov. 11, three days after the battery left.

On Dec. 7, Wyoming’s Battery A was assigned to the garrison of the town of Cavite in the Philippines, where they were stationed for the entirety of their service. The battery saw no combat during their term of guard duty. Battery A joined the Wyoming infantrymen aboard the troopship Grant on July 30, 1899, and the men were discharged on the same date as the 1st Wyoming Infantry Battalion at San Francisco. The battery suffered no combat casualties, but two men died due to non-combat causes.

Wyoming, being a state not then even a decade old, with a relatively small population, made only a minor contribution to the Spanish-American War, despite the three combat deaths its men incurred. The soldiers only participated in minor skirmishes and did not achieve any glorious victories. Their sole accomplishment was raising the U.S. flag over an abandoned Spanish army barracks.

But Wyoming fulfilled all of its federal requirements, the two units served honorably and accomplished all of their assigned tasks. It was the first active service of the fledgling Wyoming National Guard, and they fully validated the skills and fidelity of the Cowboy State. In fifteen years, they would again be summoned into Federal service, first along the Mexican Border, and then in the Great War.

Resources

- Coats, Stephen D. Gathering at the Golden Gate: Mobilizing for War in the Philippines, 1898. Fort Leavenworth, Kan.: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006.

- “First Wyoming Infantry Battalion, United States Volunteers, May 8, 1898 to September 23, 1899.” The Spanish American War Database. Accessed Dec. 12, 2017, at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~scjssawv/History/Wyoming/Volunteers_1stInfBtn.html.

- “First Wyoming Volunteer Infantry, U.S.V.” in Karl Irving Faust, Campaigning in the Philippines (San Francisco: The Hick-Judd Company, Publishers, 1899).

- Foote, Maj. Frank M. “Report of the Commanding Officer of the 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Concerning the Unit’s Actions at the Fall of Manila on August 13, 1898.” The Spanish American War Centennial. Accessed Dec. 12, 2017, at http://www.spanamwar.com/1stwyoming.htm.

- Schott, Joseph L. The Ordeal of Samar. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1964.

- “Wyoming Volunteers,” Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum Collection. Casper, Wyoming (No publisher, no date listed). This booklet, probably circa 1899, provides comprehensive rosters of all Wyoming companies in service during the Spanish-American War.

Illustrations

- The photo of the artillery battery is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the 1st Wyoming Infantry camp is from the collections of the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum in Casper, and the Passig River scene is from the author’s collection. Both are used with permission and thanks.