- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Powell, Wyoming

Powell, Wyoming

In 1907, the United States Reclamation Service established a work camp, named Camp Colter in honor of mountain man John Colter, alongside the tracks of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy in what was then Big Horn County in the northern end of Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin. Living in the middle of an arid flat a few miles north of the Shoshone River, the camp’s residents labored to complete a system of canals that would transform the desert landscape into productive, irrigated fields. On April 27, 1908, water flowed through the new canal system. The water marked an important environmental and cultural transformation, changing the flat to an ideal location for homesteaders. Residents of Camp Colter renamed their growing community in honor of famed Grand Canyon explorer and early day proponent of federal reclamation, John Wesley Powell.

Powell had warned the nation that private reclamation companies did not have the financial stability or wherewithal to complete large-scale reclamation projects. To bring water to the West, state and federal governments needed to step in to provide the tremendous capital needed to build dams and canals. This was evident with the arid region near the future town of Powell.

In 1894, Congress passed the Carey Act granting arid western states up to one million acres of public domain providing the state ensured the completion of small‑scale irrigation projects guaranteeing the reclamation of these lands. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, irrigation promoter George T. Beck and other investors contracted with the state of Wyoming to irrigate the land surrounding Cody, Wyo., by diverting water from the Stinking Water River. In 1899, Cody and his longtime show-business partner, Nate Salsbury, acquired water rights previously claimed and then abandoned by Wyoming Congressman Frank W. Mondell. Cody and Salsbury’s state permit allowed them enough water to irrigate 120,000 acres including the arid land near present-day Powell that could then be claimed under the Carey Act. This reclamation project stalled due to lack of funds and Salsbury’s death.

Hoping to lure more settlers to the region, the state of Wyoming changed the name of the Stinking Water River to Shoshone River in 1902 but still the irrigation project floundered. The same year, President Theodore Roosevelt signed into law the Newlands Act permitting the Secretary of the Interior to fund western reclamation projects from public land sales. In 1904, Cody relinquished his water rights to the federal government, which took over the project northeast of the town of Cody along the Shoshone River, now identified as the Garland Division of the Shoshone Reclamation Project.

Camp Colter’s central location within the Garland Division led the Reclamation Service, supported by businessmen eyeing the business potential of the future community, to transform the work camp into a full-fledged town. These efforts succeeded despite the efforts of W.F. Cody and the Lincoln Land Company, a partnering firm of the Burlington Railroad, to prevent the founding of Powell in hopes the nearby towns of Garland and Ralston, where these entities owned land, would develop into larger communities.

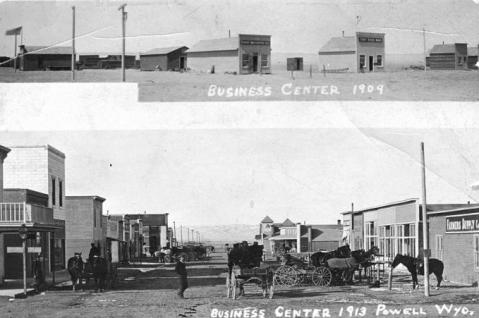

In 1908, the Reclamation Service applied to establish a post office only to discover another railroad siding held the name Colter; thus, the name Powell was substituted for the name Colter. On May 25, 1909, the Reclamation Service sold lots in the new community, an event considered by locals to be the official founding of the town, and the state of Wyoming officially incorporated Powell on May 10, 1910.

The Reclamation Service intended the wider Clark Street to be Powell’s main street; however, when merchants discovered they could purchase larger lots on Bent Street for lower prices, this street became the center of the business district. Powell’s first businesses were located in false-front wooden buildings, which proved to be tinderboxes. Large fires continually plagued the community. On Feb. 12, 1915, one fire burned down at least nine businesses before residents extinguished the flames by setting off dynamite charges. The resulting explosion broke all the windows of the surviving business on the other side of Bent Street. After the 1915 fire, the community formed a volunteer fire department and purchased a new alarm bell. When they were not fighting fires, the firemen wetted Powell’s dusty streets. After a few years, brick buildings replaced wooden structures, and oiled roads curtailed the dust.

Agriculture was the primary economic resource of Powell. Soon alfalfa, grain and bean mills sprang up along the tracks to provide regular and seasonal jobs. Beginning in 1923 Powell became the host community of the Park County Fair after reaching an agreement with neighboring Cody, the county seat, which secured the Fourth of July celebration in return. The agreement reflected clear differences between the two towns’ economies that continue today: Powell, with its farm-fostering county fair, is an agricultural hub; Cody, with its big Fourth-of-July rodeo and parade, depends on Yellowstone-bound tourists. In the mid-1920s, the Shoshone Irrigation District, a local authority headquartered in Powell, assumed control of the Garland Division from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which had been known as the Reclamation Service until 1923. Under the new agreement, the farmers organized themselves into the district, took over the operation and maintenance of the system and entered into long-term contracts with the Bureau to pay off the government’s initial investment.

Other economic developments also contributed to Powell’s population growth. In 1915, oil was discovered at Elk Basin north of Powell, and a few coal mines were developed on Coal Mine Hill a few miles northeast of Powell.

Most of Powell’s first residents, though, were business people offering goods and services to the farm families in the area, and both groups desired a strong educational system in the Powell region for their children. The first school in Powell opened in 1908 with 36 students ranging in age from six to 21. In 1911, School District 1 was formed. The following year students attended classes in a new brick schoolhouse. Due to its large service area, School District 1 operated the largest busing system in Wyoming. The Powell community voted for a 2.5-mil levy to fund the construction of Northwest Community College in 1953, and more than 1,600 Powell citizens attended the dedication of the new college facilities on May 20, 1956. The public schools, college and hospital remain the biggest employers in Powell today.

Powell’s more famous residents include publisher Alan Swallow, who founded Swallow Press in Colorado in 1940 to publish poetry, fiction and western Americana. W. Edwards Deming also grew up in Powell and went on to pioneer the new business management techniques he perfected while serving under General Douglas MacArthur when the United States helped rebuild Japan’s war‑torn economy. The Rocky Mountain Cowboy, Roy Barnes, supplemented his income by writing a few popular cowboy songs and performing on Powell’s local radio station, KPOW. Barnes’ radio career began in the 1930s and spanned 60 years.

In 1939, Powell resident Earl Durand created a national stir by leading law officials on a highly publicized manhunt. After escaping from the jail in Cody, he killed two Powell lawmen, fled to the Beartooth Mountains west of Powell and killed two posse members there. He died March 24, 1939, following a shoot‑out when he tried to rob Powell’s First National Bank. Durand’s escape and death remain the most dramatic events of Powell’s past—and, the frightening story continues to surprise visitors to this peaceful farming and education hub in northern Wyoming.

The 2010 census pegs Powell’s population at 6,314. In 1994, Powell became one of just 10 municipalities named an All-America City that year by the National Civic League.

Resources

- Bonner, Robert and Beryl Gail Churchill. Powell’s First Century – Home in the Valley. Cody: Words Worth, 2009.

- Bonner, Robert. Farm Town: Stories of the Early History of Powell. Powell: Powell Tribune, 1999.

- Churchill, Beryl Gail. Dams, Ditches and Water: A History of the Shoshone Reclamation Project. Cody: Rustler Printing and Publishing, 1979.

- Churchill, Beryl Gail. People Working Together: A 75th Anniversary Salute to Powell. Powell: Custom Printing, 1984.

- Hendricks, Cecilia Hennel. Letters From Honeyhill: A Woman’s View of Homesteading, 1914-1931. Boulder: Pruett Publishing Company, 1986.

- Johnston, Jeremy M. Images of America: Powell. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

- Richardson, Allen G. Polecat Bench. Laramie: Jelm Mountain Press, 1983.

- Turner, Lillian. “The Legendary Earl Durand,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 55, no. 3 (Autumn 2005): 48-57.

Illustrations

- The two photos of early Powell are from the collection of the Homesteader Museum. Used with thanks.

Field Trips

- City of Powell

- Powell Chamber of Commerce

- Shoshone Irrigation District, and click here for more on the history of the district.

- Northwest College