- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Otto Franc and The Pitchfork Ranch

Otto Franc and the Pitchfork Ranch

On July 24, 1878, a weary group of easterners exited their passenger train in dusty Rawlins, Wyoming Territory. They were from the East, intent on hunting the West’s vast spaces for their health and recreation. Among them was a 32-year-old German immigrant, Otto Friedrich Heinrich Franc von Lichtenstein; he would become known in Wyoming as Otto Franc.

In New York City, where Franc was in the banana-importing business with his two brothers, his doctor had advised him to seek drier climates for his health. He had not thrived in New York. In Wyoming, in “the finest & wildest country I have ever seen abounding with fish & game” as he wrote in his journal, Franc would first lay eyes on the site of his future Bighorn Basin home: the Pitchfork Ranch.

Securing horses and food, the group headed north into dry sagebrush hills. Riding the foothills, scouting for game, moving camp, sleeping under stars in the dry air, the experience benefitted Franc in ways beyond his health.

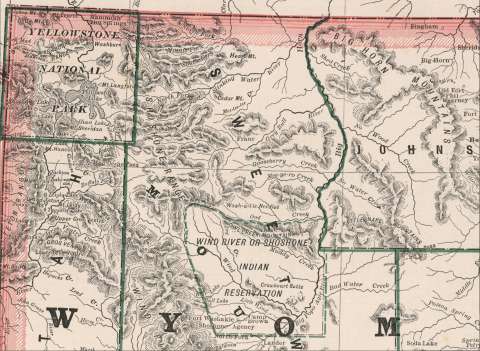

Shooting a great many elk, deer, antelope, buffalo and sage hens to feed their roving camp, they moved north toward the Bighorn Mountains. continued to the mouth of Badwater Creek on Wind River and from there traveled through at least part of Wind River Canyon into the Bighorn Basin. The basin, Franc exclaimed, was “not yet explored” and “is said to contain a good deal of game.” At present Thermopolis,Wyo., they were surprised to find a “mammoth hot Sulphur spring,” but became uneasy when they came across numerous American Indian trails and camps. Wishing to avoid unwanted encounters, they returned to Rawlins and the East.

The next year Franc returned, and ventured farther north into the basin, eventually locating a wide natural pasture on the upper Greybull River along the eastern foothills of the Absaroka Mountains. Indians and buffalo still frequented the area, but Franc understood he could locate a large open-range cattle operation there. He would make himself prominent among the area’s early white pioneers.

Early life

Otto Franc was born in 1846 near Frankfurt, then part of the German Confederation. Little is known of his childhood, but it appears he was from an ambitious family with fortunate means and connections, elements he later put to good use.

After receiving an education, Franc left his homeland in 1866 to join his two older brothers, Charles and Carl, in New York City. There they were running a prosperous business importing bananas from a plantation they owned in what then was part of Colombia, on the isthmus of Panama. When Otto arrived in New York, they were running a fleet of vessels bringing the fruit from the Caribbean and distributing it to their American clients.

The Pitchfork

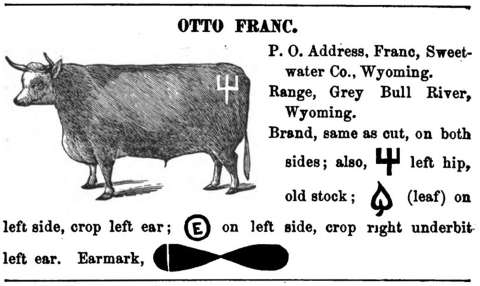

Franc located his headquarters on the upper reaches of the Greybull River in a wide valley just upstream from an outcropping known to local tribes as Papypo Butte, and began building a cattle herd. He trailed in 1,200 Hereford shorthorns in from Oregon and adopted a pitchfork brand to mark them. He bought Herefords in the Gallatin Valley of western Montana and trailed them south into the Bighorn Basin, letting them forage on the open range. There is no clear census of Franc’s early herds, but 1880s Fremont County tax rolls assess Pitchfork herds at six to seven thousand.

Though a pioneer, Franc was not the first cattleman to locate in the Bighorn Basin. While Franc was scouting the upper Greybull in 1879, Judge Charles Carter of Fort Bridger in southwestern Wyoming had sent his foreman Pete McCulloch into the Big Horn Basin with a cattle herd and a directive to locate on the ranges of the Stinking Water, later renamed the Shoshone River. Henry Lovell came into the basin that same year and founded a ranch along the Bighorn River. As the 1870s turned into the 1880s other cattlemen located along the mountain streams and wide river valleys of the Bighorn Basin.

In the summer of 1880 Franc started building permanent structures at his headquarters. He first built a small cabin of cottonwood logs. A few years later he built a larger main house with adobe walls eighteen inches thick, allegedly to protect against Indian attack. The original cabin became a blacksmith’s shop, and he added a detached cookhouse and a bunkhouse for his hands.

Initiated as a business venture with his brothers, it soon became clear the ranch was best left to the indefatigable work ethic of the youngest Franc. In the fall of 1884 Otto’s brother Carl visited to get a look. But he quickly returned to the banana business. Otto eventually bought out his brothers’ shares in 1896 and became sole owner.

Otto Franc, diarist

Franc kept a daily diary on the Pitchfork; entries from the end of 1886 to 1903 have been preserved at the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyo. Primarily, the entries noted weather conditions but often recorded various jobs and projects occupying Franc and his workers. Below are a few selections:

“December 3, 1887- Arrived this evening from the bull roundup. We had trouble crossing the cattle over Wood River on account of the ice; we had to leave them in the corral over night; we have had splendid weather with the exception of a small storm; Squires [a cowboy] and myself took the cattle from No.2 pasture and put them in the meadow. I discharged Gleaver [John Gleaver, the ranch foreman] in Buffalo Basin on Nov 29th, he is getting very slack.

May 8, 1888- 32 above, 5am, clear- All hands work on the ditch; I take Bruno [a horse] and go hunting, after cruising around a long time without seeing anything I strike a band of elk on the head of Sunshine Creek. I kill two and load Bruno with meat; I have to lead him and arrive at the ranch hungry and tired at 9pm; it rains a few drops in the evening.

May 17, 1888- 26 above, 5am- It has stopped snowing and looks like clearing up. Blowing hard from the N.W. Avent [Cicero Avent the ranch foreman] and the men start on the roundup. I keep 3 men here. We brand 5 of the milk cow’s calves; the weather looks very threatening until noon when it clears up; we drive stakes to the 90 young trees which we have planted; turn out the big steer calves to the milk cows. Straatman irrigates.

June 12, 1888- Clear, a little warmer; the men get done with Timber Creek dam, turn on water and come to the ranch, make a lateral ditch in the north pasture; sow radishes and lettuce; irrigate the garden; river higher than it has been this year.

July 15, 1888- A little cloudy cooler; go to roundup on Franc’s Fork, come home at 6pm. The freighter has arrived with a load of lumber, 5 men are there asking to be hired for haying, the flies are bad until one gets high on Gray Bull then there are none.

July 26, 1888- Partly cloudy; we stop mowing in the forenoon to let the stacking catch [up]; commence raking in the upper field, commence hauling and stacking after dinner; after working 1 hour it rains very hard and we have to stop; we have to scatter out again all the raked hay; Cross [a cowboy] lets his horse run away with the rake and smashes both wheels; we discharge Cross.

December 5, 1888- 13 above, clear still; we separate the big calves from the cows and put them into the south pasture; we butcher 3 steers, 1 was a big jam and goes to the chickens, the other 2 are for consumption, all the men quit because I reduce wages to $30.11; I keep just one man at $40.00. Avent resigns his place as foreman to go into business for himself.

March 18, 1889- 19 above, partly cloudy. Scott commences to work, we bring in 2 saddlehorses to break them to harness; haul manure and firewood and repair fence; Dye [a local cowboy] calls upon a social visit, I accuse him of having stolen several things here whereupon he ends his visit abruptly, we put most of our horses into the Sunshine Hills where there is better feed than near the mountains, saw the first bluebirds.

April 22, 1889- 36 above, partly cloudy; Merrill [George Merrill the ranch foreman] and 6 of the men go to Franc’s Fork to camp to work on the big ditch and make headgates; we plow ditches in the meadow; it is 62 above at 10am, after that the wind blows very hard from the west and clears up toward 4pm; then the wind dies out and it clouds up again; it is very dry; the young grass is dying, the streams are so low that Timber Creek sinks before it reaches the meadow and we have not a drop of water for the garden.

A growing community

As there was little in the way of community or government, Franc took the initiative to form his own institutions. In 1882 the U.S. Postal Service created the first post office in the basin. It was located at the Pitchfork and named “Franc”. Otto Franc was named postmaster. A few years later it was moved downriver to the site of the growing town of Meeteetse.

By the end of 1883, there were numerous other ranches in the basin. Otto Franc was no longer in such an isolated country.

Other operations now included George Baxter’s LU Ranch on Grass Creek, Harry Cheeseman’s operation on Wood River, Joseph Carey’s YU Ranch on the lower Greybull, and Andrew Wilson on Meeteetse Creek. Just above the Pitchfork was the Z-T, owned by an eccentric English remittance man, Richard Ashworth, and the Four Bear Ranch of the famous grizzly hunter Col. William D. Pickett.

In the early days Franc had to hunt frequently. He often mentioned riding out into the hills to looks for bands of elk. He also shot small game around his ranch.

In those days there were still a few buffalo along the foothills of the Absarokas. They often gave Otto Franc trouble as he was erecting sawbuck fences around his homestead. Old bulls would routinely destroy the new fences, much to Franc’s frustration. Later, he told of shooting at several of the hardheaded animals from his porch. But the few remaining buffalo in the Bighorn Basin were soon killed out by hide hunters, visiting sportsmen and local cowboys.

A lover of fresh eggs and vegetables, Franc also raised chickens and tended a large garden at his ranch. He regularly harvested abundant amounts of cabbage, perhaps to remind him of Germany.

Any provisions and ranch equipment Franc and his neighbors could not acquire locally had to come in by freight wagons over miles of often impassible wagon roads. This was extremely expensive and only arranged as a last resort.

On April 9th, 1883, Franc penned a letter to the Board of Trade in Billings, Montana Territory, asking them to help finance a bridge across the Stinking Water (now Shoshone) River to improve the primitive road running the length of the Bighorn Basin north toward Billings.

“Heretofore we have been getting our supplies from Fort Washakie and Lander,” Franc explained. “The road to those places is wretched in the extreme- almost impassible. The road from Stinking river to Billings is very good. South of the Stinking River it is not so good and requires some work. Our principal bug-bear, however, is Stinking River…[…]…The only remedy would be to build a bridge across it.” Making the case that a sturdy bridge and a good road would bring the trade north, Franc helped convince the leaders of Billings to improve the transportation infrastructure in still largely undeveloped northwest Wyoming.

The open range cattle business

Open range cattle ranchers in the Bighorn Basin and throughout most of Wyoming depended at the time on the public domain; that is, ranchers rarely homesteaded or accumulated large tracts of land for their stock. Instead, they headquartered on a small piece of homesteaded land with easy access to water and grazed their herds on the open range for free. This arrangement was profitable as time and money expended on actual animal husbandry was limited. They rarely concerned themselves with thoroughbred animals or expensive breeding stock. Instead, they preferred hardy, rangy animals that could fend for themselves through the winter.

Throughout most of the year the cows were in a semi-wild state. Open-range ranchers rounded up their stock twice a year, once in the spring to brand and castrate the new calves, and again in the early fall to gather healthy fat animals to be sold. The system was cheap compared to more labor-intensive livestock operations elsewhere in the country. There was little incentive to conserve the quality of the range and there were few barriers to running as many cattle as possible. Eventually, the overgrazing of the open range and the increasing competition for land with new homesteaders would bring violence to the range in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

The roundups were communal. Each ranch had its representatives participating, to separate their employers’ cattle and ensure the best interest of their outfit.

Tom Osborne, an early cowboy on the Pitchfork, recalled the roundup: “Franc had, on average, eight cowboys, a horse wrangler, and a round-up cook. They would start in April or May and be on the range most of the summer. His range extended from Clarks Fork to Owl Creek, the south side of the Big Horn Basin and all along the Rocky Mountains.” This is a huge stretch of country, running along the mountain front from north of what is now Cody, Wyo. to west of Thermopolis, Wyo.

Changing circumstances

As the Wyoming range became crowded, cattlemen found themselves cut off from more and more of the free grazing land to which they had enjoyed access only a short time before. They had to file claims to secure more land and build fence to contain their once free-ranging herds.

Unlike many cattlemen, Franc realized the changing circumstances required changing operations. The Pitchfork was one of the first ranches in the area to cultivate an annual hay supply. Ranch hands slowly turned the wide sagebrush flat between Papypo Butte and Timber Creek into bountiful fields of alfalfa and timothy. They removed countless river stones and leveled bumps and draws. In 1897 Franc’s men turned the wide natural pasture at the mouth of Papypo Creek into a field where he reported growing 12,000 tons of hay.

Many of the men he had hired for this work were Mormon settlers who had recently formed a small farm community 50 miles downriver. With their own farms still struggling, the men appreciated the jobs Franc offered, and named their community Otto in honor of the rancher upriver.

Franc also hired men to build irrigation ditches and an underground drainage system to make hay crops more reliable. This proved prudent. Franc’s herds usually emerged from harsh winters in much better shape than his neighbors’ herds did.

As time went on, he located the best winter ranges. In the fall he directed his cowboys to move most of his herds to Buffalo Basin and the lower Greybull country, where winter was often not as severe. And he began importing purebred Hereford bulls from the Midwest.

When Franc first established his ranch, the nearest rail line was more than 150 miles north at Huntley, Montana Territory, east of Billings. He recognized it made no sense to trail cattle all that way only to sell them at the shipping point lean and hungry from the long drive. Instead, he made a deal with Crow Chief Plenty Coups, whereby Franc could graze his cattle on reservation land near the stockyards. Now, every spring, he could separate from his range in the basin the cattle he wished to sell and slowly move them north to the reservation during the summer. They arrived at the railroad fat and prime for sale on the Chicago market later in the fall.

While many of his neighbors struggled from harsh winters, range droughts and low beef prices, Franc made preparations to avoid disasters. He was shrewd, but it also appears he was genuinely curious. In his journals he recorded the return of bird species in the spring and the habits of animals near his home. He bought a bicycle and rode on roads and over the range, undoubtedly the first cowboy in the area to abandon a horse for a pair of wheels.

Like many of his neighbors Franc did not always spend the winter on his ranch. Instead, he often chose warmer climes or family back east where he could conduct business in more civilized settings. He passed the winter of 1883 with his family in New York City, but later came to prefer temperate southern California as his winter home. In 1898 he spent two months off the coast on Catalina Island, fishing and sailing.

Life on the ranch

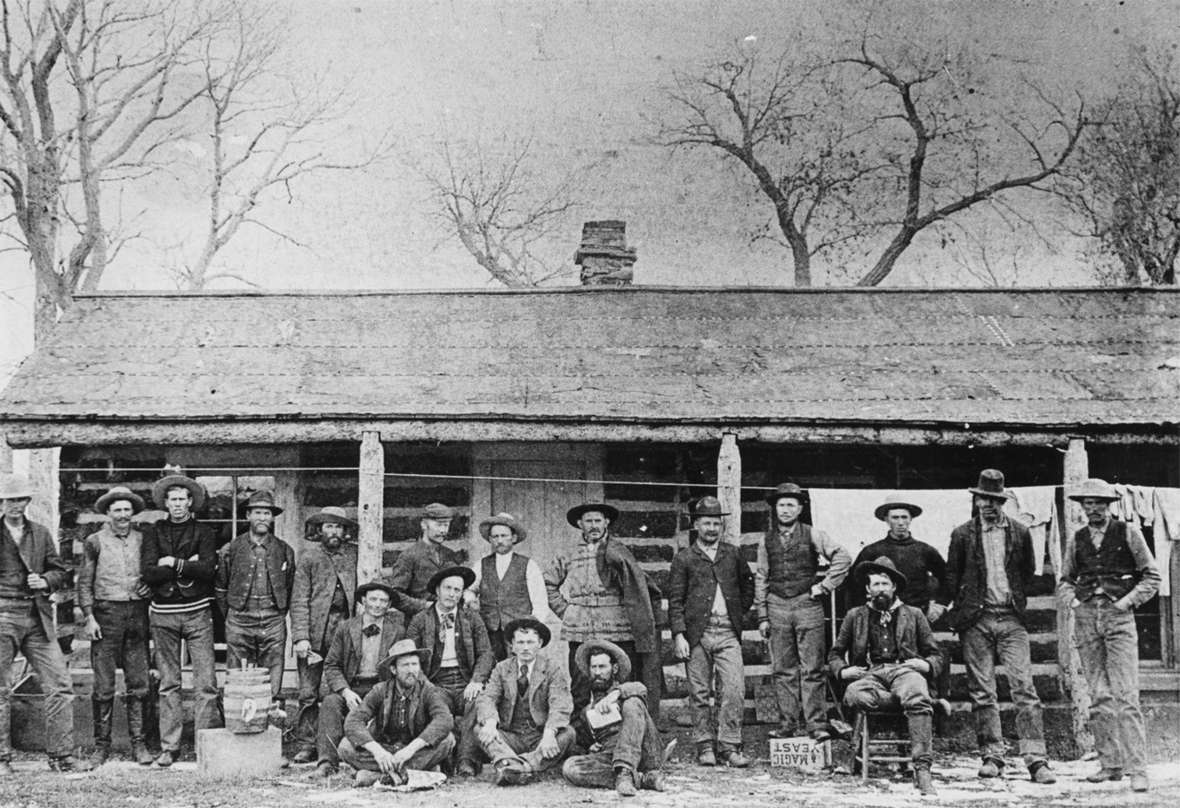

Franc employed many local men as cowboys, ranch hands and irrigators, but often had to travel to Billings to find workers. While many in the area appreciated the work, Franc also had a reputation for being strict, regularly firing cowboys for laziness or drunkenness. The Bighorn Basin was still largely lawless in the 1880s and 1890s, and a place of refuge for many who wished to lose themselves or disappear.

And Franc had his own odd habits. As a lifelong bachelor he was used to living on his own terms and, never having to reconcile himself with the needs of others, he became extreme in his demands for personal neatness. “Franc was the clean type,” one of his long-time cowboys observed, “fussy as an old maid. He was always getting after the men for not keeping their clothes clean.”

However busy Franc kept himself and his cowboys, he also provided time for solace. The Rev. Louis Thompson traveled the basin from end to end holding services in tents, cabins, private homes or wherever he could assemble a group. The Pitchfork was one of the largest operations and the Rev. Thompson was pleased to provide services to the cowboys. He recalled the Pitchfork in his pamphlet about his circuit riding days:

“Otto Franc kindly granted me the privilege of holding services in his house, his large dining room being used for this purpose. He usually had between forty and fifty men in his employ, they formed an interesting audience. All cowboys – how different were these daring riders of the plains as they sat with respectful attention before me, from the idea usually entertained by people who know nothing of their lives and characteristics and have formed their estimate of them from the baseless representation in pernicious literature. My cowboy audience at Mr. Franc’s were always respectful in the attention they gave and greater deference and consideration could not have been shown me had they been gentlemen of wealth, education and leisure in the advanced east.”

Though the services at the Pitchfork seem to have been popular among residents of the upper Greybull country, the Rev. Thompson later built the first church in the Big Horn Basin at the town of Otto.

In a region where the population was small and competent leaders few, Franc could not help being drawn into politics. He served as justice of the peace with a jurisdiction covering a large part of the Bighorn Basin. In this capacity Franc oversaw the trials of cowboys, the surge of rustling activity in northwest Wyoming and slow implementation of nascent wildlife protection in the Bighorn Basin. Although Franc was known among locals as “The Little Man—” a passport application listed him as 5’ 2”—he cast a big shadow over the dwindling lawlessness in Wyoming.

Franc and the range wars

And though the Bighorn Basin was removed from the events of the Johnson County War by a sizable mountain range, it was not immune to the antipathy that had been developing between the owners and managers of the large ranches and the small-ranch homesteaders.

By 1892 the scene in both the basin and the entire state was tense. On March 2, 1892, Otto Franc wrote in his journal, “I start for Billings to attend a meeting of stockmen of northern Wyoming to consider ways to protect ourselves against rustling.” And March 30:

“I start down the Greybull and take some rifles and ammunition with me to find Merrill [George Merrill, his ranch foreman] and his men. I heard last night that one of Lovell’s [Henry Lovell] men while hunting horses on Dry Creek was turned back by a man with a rifle. This has got to be stopped and I will see what we can do about it.”

Early in April 1892, about 50 large-ranch owners and hired gunmen from Texas invaded Johnson County east of the Bighorn Mountains to kill rustlers. Those events ended with a few deaths, a counter-siege of the invaders, their rescue by the U.S. Army and their eventual release from custody.

At the same time, other large ranchers around the state began employing range detectives too. Franc assigned John T. Wickham, an employee, the duties of detective. In the fall of 1892 Wickham and two other range detectives were involved in the killing of Jack Bedford and Dab Burch, two alleged rustlers.

Bedford and Burch had come to the basin as cowboys with aspirations of starting their own ranches. When they were accused of rustling a few horses from the open range on the No Wood River, on the east side of the basin, a trial ensued, following which Bedford got into a physical altercation with H.B. Peverly, a range detective and witness. Now convicted of disturbing the peace, Bedford and Burch were ordered to be taken to the Johnson County jail across the Bighorn Mountains in Buffalo, Wyo.—as Johnson County then extended all the way to the Bighorn River. En route they were purportedly murdered by Wickham, Peverly and Joe Rogers, all men in the employ of the big ranches in the region.

Franc at the time was north of the Wyoming border on the Crow Reservation overseeing shipment of his beef. Anxiety took over the camp when news came of the deaths of Burch & Bedford. Franc had arrived at the roundup on the Reservation with a huge amount of ammunition in his wagon, as if he was expecting trouble.

The whole affair drove Franc into a state of alarm from which many claim he never recovered. From then on, he kept a bodyguard close at hand. That he was somehow implicated in the whole murderous affair is evidenced by numerous journal entries. On Dec 5th he wrote, “Billy Taylor arrives and brings me message that the rustlers are making threats to take Wickham to Buffalo.” And again on Dec 16th he wrote,

“I returned last night from Billings. I was summoned there by special messenger because it was thought the rustlers had decided to kidnap Wickham or have him arrested, and then take him through the Big Horn Basin on his way to Buffalo, waylay him and kill him. While I did not believe the report to be true, still I sent Wickham off somewhere where the rustlers won’t find him.”

By the spring of 1893 the matter was still not resolved. In March of that year his foreman George Merrill returned to the ranch with news that spurred Franc to leave the next day for Billings. On March 30, 1893, Franc wrote in his journal, “I return from Billings. I have provided for the safety of Joe Rogers and Wickham. During my absence a sheriff posse has been here to arrest Rogers but found him gone.” The range detectives had finally been charged with first-degree murder in Buffalo, the seat of Johnson County, but evidently Franc had been forward and moved the men to Montana before the law could be applied.

In addition to the Burch and Bedford affair, 1892 also saw Otto Franc charge a young Butch Cassidy and his accomplice Al Hainer with rustling horses. Franc stood as a witness against them at their trial in Lander. Later convicted and sentenced to a stint in the Wyoming State Penitentiary, the ordeal allegedly spurred Cassidy into a blossoming life of crime.

Clearly, the whole fiery and violent affair between the rustlers and cattlemen had a profound effect on Franc and his disposition to the world around him. As time went on, however, tensions began to subside, as the once dominant owners of huge ranches realized they would have to share the range.

An enigmatic death

Otto Franc’s death will probably always remain enigmatic.

On the evening of Nov. 30, 1903, Franc went for a walk along the north side of the Greybull River just east of his ranch house. He carried an exposed-hammer double-barreled shotgun in case he happened on any rabbits or ducks.

A short while later a single shot was heard by the cowboys back at the ranch. Figuring their boss had found his quarry they thought nothing of it until, well after dark, Franc had failed to arrive home. A small party found Franc’s body lying face up about three feet from a barbed wire fence with his 10-gauge shotgun still propped up nearby. The right barrel was empty as the shell had been fired and the left was loaded with the hammer still at full cock.

Franc’s death shocked his neighbors but was reported in local newspapers as a tragic accident. Investigators theorized that after having crossed the fence himself, Franc had begun pulling the gun towards him through the wire when it discharged a blast into his chest just above the heart. He died instantly. There was no sign of a struggle. So it was, as one newspaper reported, that “the man who faced a thousand dangers of frontier life without harm met death in this unfortunate manner”.

Other speculation questioned the conclusion it was an accident. Some doubted that Franc would have been so foolish as to carry around a loaded shotgun with the exposed hammers primed, much less pull that same loaded and cocked gun through a barbed wire fence. Others immediately pointed to the enemies Franc had made in his dealings with rustlers and encroaching sheepmen, suspecting foul play.

Regardless, it was clear to everyone that a figure of longstanding importance was no longer part of the community. Dead at 55, Otto Franc was buried in the Meeteetse Cemetery. The funeral was attended by hundreds, the largest Bighorn County had to that point ever seen. Beyond Wyoming, too, Franc was well known in the stock-raising community. “Mr. Franc was widely known and recognized as a prince among men,” the Chicago Livestock World reported.

Franc’s legacy

Franc’s death marked the end of an era. Having started his operation when Crow, Arapaho and Shoshone people were still hunting buffalo on the flanks of the Absaroka Mountains and having seen the country fill with cattle, Franc lived to witness the open range transform into a landscape controlled by irrigation and barbed wire fencing.

Five miles upriver from the Pitchfork Ranch a large tributary enters the Greybull from the south. It initially appeared on maps as Wolf Creek but since the 1890’s had been called Franc’s Fork (sometimes “Frank’s Fork”). This stream runs from mountains where it begins in large cirques on the eastern flanks of Franc’s Peak, at 13,158 feet the highest peak in the Absarokas.

In 1884 Otto Franc and his friend Thomas Osborne climbed the peak as part of their regular efforts to better understand the landscape. From the top, Franc could see the Tetons and Yellowstone Park to the west, and to the east the Greybull River Valley, most of the Bighorn Basin and the Bighorn Mountains beyond. We can hope this restless man stopped long enough to enjoy the view.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “Accidently Killed Himself!” Cody Enterprise, December 3, 1903.

- “An Accident Beyond Doubt.” Billings Gazette, December 11, 1903.

- “An Important Letter.” Billings Daily Herald, April 26, 1883.

- Deane, Josh, “Big Horn Basin Cattle War Kills Two Men.” Cody Enterprise, September 21, 1938.

- “Death of Otto Franc.” Big Horn County News, December 5, 1903.

- “Early Cowmen of Big Horn Basin.” Big Horn County Rustler, December 16, 1910.

- Franc Von Lichtenstein, Count Otto, MS 10, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyo.

- “Mammoth Stock Farm.” Wyoming Tribune, April 11, 1904

- Osborne, Thomas, Unpublished Manuscript, Park County Archives, Cody, Wyo.

- “Otto Franc is Dead.” Red Lodge Picket, December 3, 1903.

- “Otto Franc Killed.” Chicago Livestock World, December 1, 1903.

- “Otto Franc Shot.” Wyoming Stockgrower & Farmer, December 1, 1903.

- “Otto Franc’s Death Was Not Intended.” Butte Daily Post, December 12, 1903.

- “Victim of Accident.” Carbon County Chronicle, December 8, 1903.

- Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association, Cattle Brands. Chicago: J.M.W. Jones Stationary & Printing Co., 1883.

Secondary Sources

- Edgar, Bob & Jack Turnell. Brand of a Legend. Cody, Wyo: Stockade Pub., 1978.

- Rollinson, John K. “Brands of the Eighties and Nineties Used in the Big Horn Basin, Wyoming Territory.” Annals of Wyoming 19, no.2 (July 1947): 65-76.

- ______________. Wyoming Cattle Trails. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1948.

- Wasden, David J. From Beaver to Oil. Cheyenne, Wyo: Pioneer Printing & Stationery Co., 1973.

- Woods, Lawrence M. Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin to 1901: A Late Frontier. Spokane, Wash: Arthur H. Clarke Co., 1997.

Illustrations

- The 1890 studio portrait of Otto Franc is from the Billings, Mont., Public Library. Used with thanks.

- The photos of Franc on horseback at shipping time and of the cowboys on the Pitchfork bunkhouse porch are from the Meeteetse Museums. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Papypo Butte is by Emily Swett. Used with permission and thanks.

- The image of the steer with the Pitchfork brand is from page 36 of the the Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association’s 1883 Wyoming Brand book, available in many Wyoming libraries’ special collections.

- The photo of Franc’s adobe house is from Park County Archives in Cody, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.

- The two photos of Pitchfork Ranch buildings and the barn and haystacks are from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The map is from the David Rumsey Map Collection. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the headstone is from Findagrave.com. Used with thanks.