Wyoming Presidents’ Days

Recently, we got a question from people who work at the Wyoming State Capitol: Is it true that Teddy Roosevelt once gave a speech from the second-floor balcony on the front of the building? It seemed like an interesting question as we approach President’s Day this election year.

That’s the balcony directly above the main entrance—if you know the building you know it would be a perfect spot for a speech on a sunny day. As it turned out, no, TR did not speak from that balcony; the Cheyenne Leader makes it clear he spoke instead from a bunting-draped platform at the corner of what are now 15th and Carey, nine blocks away. It was Decoration Day—now called Memorial Day—1903. The speech came near the end of a long trip; WyoHistory.org Assistant Editor Rebecca Hein describes it as “a 14,000-mile lasso flung to rope the whole American West.” Over five and a half weeks Roosevelt averaged seven or eight speeches per day.

In April, he spent two weeks in Yellowstone camping with an entourage and the wildlife writer John Burroughs. Then he headed east to catch a train to the Southwest, and on the way gave a speech in Newcastle, Wyoming. From Omaha he headed west again: Santa Fe, Los Angeles, Yosemite for two days with John Muir, San Francisco and then east via Salt Lake City to Wyoming. A quick, 20-minute speech in Evanston drew a crowd of 7,000.

Next day he stopped in Laramie and got on a horse. With ten other bigwigs—mostly politicians and law enforcement—he rode 65 miles over the hill to Cheyenne, changing mounts three times. They arrived by 4 p.m. At 7, he spoke for half an hour to a crowd of 10,000. His speech, like others on the tour, emphasized conservation, good citizenship, resource development and the new federal commitment to large-scale irrigation. During two more days in Cheyenne he lunched with former U.S. senator and future governor Joseph Carey and rode a horse to Sen. Francis Warren’s ranch for an evening barbecue.

Wyoming, the most deeply western piece of the West, burnished this president’s image. Counting his weeks in Yellowstone, he spent far more time here than anywhere else on his tour. He was the one-time Dakota ranchman, the one-time mounted colonel of the Rough Riders, the man of action who could ride a horse all day and give a rousing speech in the evening. Two years after ascending to the presidency when William McKinley was assassinated, Roosevelt was now a year away from starting his first run for president. He was, as we say these days, strengthening his base.

But Roosevelt was not the first president to visit Wyoming—that was Chester A. Arthur, in 1883, when Wyoming was still a territory. And Arthur’s trip was a 23-day fishing trip—very much about policy but not about electoral politics. Like Roosevelt, Arthur had been a political insider in New York City before becoming vice-president, and had ascended to the presidency after the president, Garfield in this case, was assassinated. But he came to Wyoming out of concern for how the new Yellowstone Park was being run—and to catch trout.

Yellowstone, under the U.S. Department of Interior, was about to be opened wide to developers. The new Yellowstone National Park Improvement Company had plans for logging, ranching, mining and a railroad, and was already cutting timber for a 250-room hotel at Mammoth Hot Springs and allowing hunters to kill game to feed the construction crews.

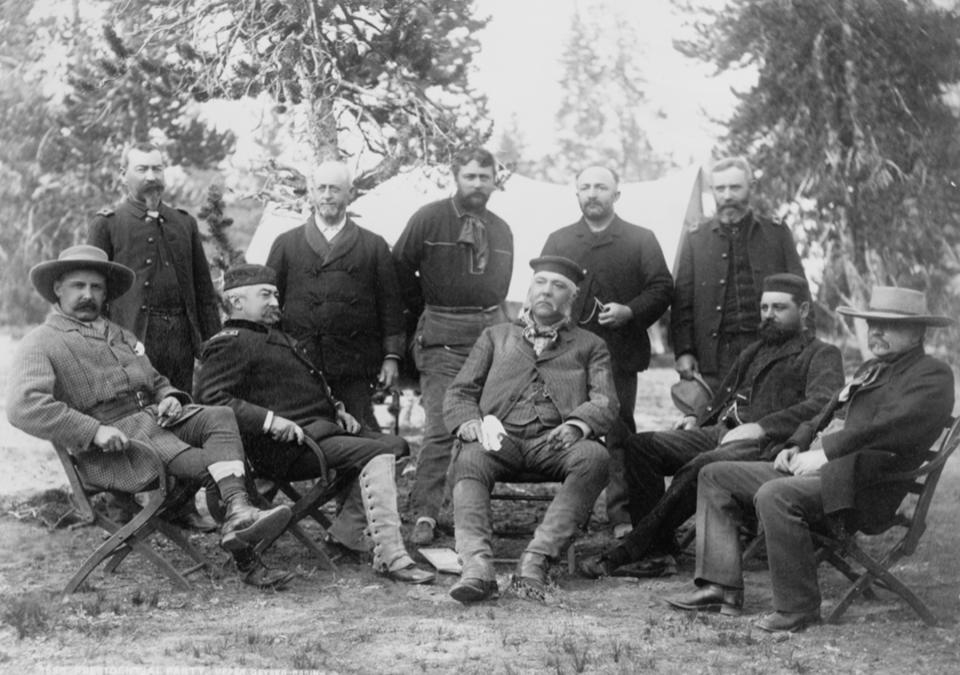

“Yellowstone,” writes WyoHistory.org author Dick Blust, “was on track to become another Niagara Falls at a time when ‘Niagarizing,’—destructive exploitation of natural wonders for profit—was a term in common use.” Philip Sheridan, the former Union cavalry commander, now commanding general of the U.S. Army, wanted to preserve Yellowstone as it was. He and a group of other conservation-minded advisors persuaded Arthur that a three-week horseback trip to Yellowstone, with a 75-man cavalry escort, was a good idea.

From the Union Pacific they traveled north by wagon to Fort Washakie on the Eastern Shoshone Reservation, where Shoshone Chief Washakie and Northern Arapaho Chief Black Coal pleaded with the president and his party to oppose propsals then circulating to do away with tribal ownership of Indian lands and replace it with ownership “in severalty.” Within four years, these pleas would be ignored.

From Fort Washakie they rode horseback with pack animals northwest over the Wind River Range to Yellowstone. In the end Arthur threw his influence behind the conservation lobby, commercial concessions were regulated and sharply curtailed, there was never a railroad and the early developers went bankrupt. Sheridan’s influence led to the shift of management to the U.S. Army until 1916, when the National Park Service was founded.

Roosevelt was by no means the last president to visit Wyoming either. But subsequent visits have been brief. Harry Truman came to Wyoming in 1951 for the dedication of Kortes Dam. As a young army officer, Dwight Eisenhower crossed Wyoming in 1919 and campaigned here in 1952 on his first run for president. On a conservation tour of the West, John F. Kennedy stopped in Laramie and Cheyenne two months before he was shot. Lyndon Johnson visited Casper twice, first as vice-president in 1962 and as president in 1964. Bill and Hillary Clinton vacationed several times in Jackson Hole. And Donald Trump, no longer president, came to Casper in May 2022 to campaign against Rep. Liz Cheney.

Surely more presidents will make the trip, and we’ll be able to list more presidents’ days.

Read:

President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1903 Visit To Wyoming

The President Arthur Expedition: The Fishing Trip That Helped Save Yellowstone