- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Tri-Territory Site: Outpost of Invisible Em...

The Tri-Territory Site: Outpost of Invisible Empires

The history of America’s massive territorial expansion from the beginning of the 19th century is a complex story of treaties, purchases, annexations, compromises and conquest. At various times, Great Britain, France, Spain, Mexico and the one-time Republic of Texas all laid claim to vast territories ranging from the Mississippi River west to the Pacific—without, of course, any regard for the ownership rights of the native peoples who were already there.

On a remote sagebrush flat in Sweetwater County, Wyo., a few miles northeast of Steamboat Mountain, a simple, seldom-visited monument commemorates a place that, on maps, was once very important—though until the 1960s it was invisible. The monument marks the site on the 42nd parallel of north latitude where the boundaries of the three dominions that would make up the bulk of the American West outside of Texas all met—the Louisiana Purchase, the Oregon Territory and Mexico: the Tri-Territory Historic Site.

The Louisiana Purchase

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson’s diplomats negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with France. At a single stroke, the acquisition of 828,000 square miles at a price of $15 million nearly doubled the size of the United States. The Purchase’s eastern boundary was the Mississippi; in the West, the Continental Divide. The states carved out within its borders would come to be Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma in their entirety, plus most of the land in Louisiana, Colorado, Montana, Minnesota, Montana, Kansas and Wyoming.

To explore the Purchase, seek the theoretical Northwest Passage, establish an American presence in the Oregon Country, conduct scientific and economic studies and establish trade with Native American tribes, Jefferson commissioned Lewis and Clark’s epic Louisiana Purchase Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, in 1804.

For more than two years, from May 14, 1804, to Sept. 23, 1806, Capt. Meriwether Lewis, who was Jefferson’s secretary, and Lt. William Clark, the expedition’s co-commanders, led a party of five non-commissioned Army officers, 30 soldiers, and a small assortment of civilians, including the legendary Lemhi Shoshone woman Sacagawea. Theirs was a two-way, 8,000-mile journey by keel boat, canoe, on horseback and on foot from present-day eastern Missouri through what are now Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Oregon to the Pacific Ocean and back, with the loss of only one member of the expedition and two Blackfeet warriors.

The Oregon Country

The “Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America,” signed in London on Oct. 20, 1818, set the boundary between the United States and British North America –what’s now western Canada—as the line of the 49th parallel of north latitude from “Lake of the Woods [in present-day northern Minnesota] to the Stony Mountains [the Rocky Mountains].” West of those mountains was the region known to Americans as the Oregon Country, while the British called it the Columbia Department. On paper, the two nations agreed on joint control over the area, but in fact the Hudson’s Bay Company, the powerful Anglo-Canadian fur trading enterprise, took serious measures to expand its business there and keep American fur traders out.

By the mid-1840s, however, the tide of American emigration to the Oregon Country along the Oregon Trail, encouraged by expansionists in Congress and elsewhere, brought steadily rising pressure on the U.S. government to remedy the situation. The result was a series of negotiations with the British, leading to the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

The treaty ended the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, setting the boundary between the United States and British North America as the 49th parallel all the way west to the Pacific, with the exception of Vancouver Island, which remained British. Those living south of the 49th parallel were declared American citizens, and those north of the line became British. Two years later, in 1848, Congress organized the American half of the region as Oregon Territory, and formed Washington Territory from it in 1853.

The southern boundary of the Oregon Country/Oregon Territory was the 42nd parallel of north latitude running from the Rockies to the Pacific; the region south of that line was Mexican territory.

Mexico and the Mexican Cession

James K. Polk of Tennessee, who served as the 11th president of the United States from 1845 to 1849, was an ardent expansionist. He was committed to Manifest Destiny, the widespread cultural belief that America was destined to expand its dominion completely across the continent to the Pacific. It was Polk who advocated the annexation of the Republic of Texas and signed the legislation making it a state in 1845, and also led the negotiations with Britain that resulted in the Oregon Treaty of 1846 and American absorption of the Oregon Country.

The Texas-Mexico border had long been the subject of a bitter dispute. In September of 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a prominent lawyer, to Mexico City to negotiate an agreement that would settle the Rio Grande as the international boundary. Slidell also carried with him Polk’s offer to purchase California and the province of New Mexico, (which would come to encompass New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and swatches of three additional states), for a sum of up to $30 million.

When the Mexican president, José Joaquín de Herrera, refused to see Slidell, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed region between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers and began preparing a war message to Congress. Before he could deliver it, however, he learned that Mexican cavalry had crossed the Rio Grande and attacked a small detachment of Taylor’s troops, killing 11 and capturing 52. In a quickly revised war message delivered to Congress, Polk declared that Mexico had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” War was officially declared on May 11, 1846.

The conflict—highly controversial in the United States—ended two years later with an American victory on Feb. 2, 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. The Rio Grande was affirmed as the southern boundary for Texas, and, for $15 million, the United States took possession of what are now California, Utah, Nevada, nearly all of Arizona, a large portion of New Mexico and significant sections of Wyoming and Colorado. This latest acquisition of some 529,000 square miles became known as the Mexican Cession.

Thus it was that by 1848, the overwhelming bulk of what would come to be known as the West was in American hands.

The Tri-Territory Historic Site

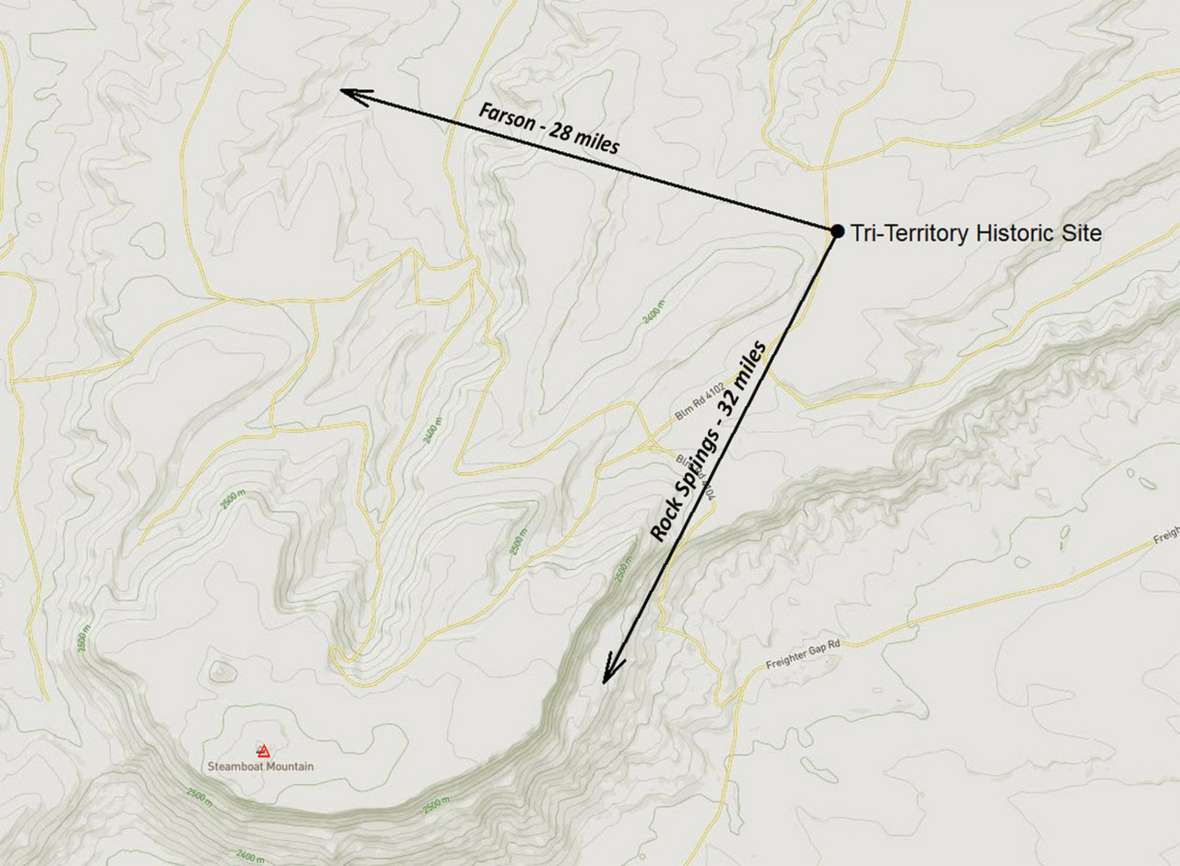

In the 1960s, the Kiwanis Clubs of Rock Springs, Lander, Riverton and Rawlins, Wyo. worked with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to create a monument in Sweetwater County at the point where the Louisiana Purchase, Oregon Country and Mexican Cession met, at the intersection of the 42nd parallel of north latitude and the Continental Divide. The coordinates are 42 degrees north latitude, 108 degrees, 55 minutes, 1.7 seconds west longitude.

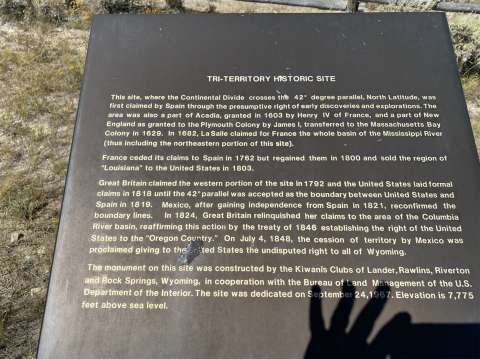

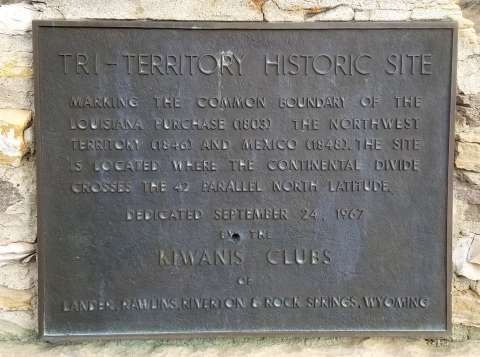

Dedicated on Sept. 24, 1967, the heart of the site is a bronze plaque mounted on a masonry monument and three flagpoles to represent Britain, Mexico and France, with a fourth atop the monument itself for the United States.

Ironically, the plaque itself later presented a problem when the site was proposed for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Writing for The American Surveyor in June 2015, Henry J. Kessner, P.E., P.S., described the situation:

There was an attempt by the Kiwanis Clubs and the BLM to include the Tri-Territory Site in the National Register of Historic Places. BLM officers vigorously pursued the proposal through the Wyoming Recreation Commission. The Commission cited two weaknesses in the BLM proposal, one of which could be corrected and another ‘which can be in no way avoided.’ The first weakness to the proposal, that which could be corrected, was the wording on the plaque which read, in part ‘...Louisiana Purchase (1803) The Northwest Territory (1846) and Mexico (1848)’. The reviewing historian, Ned Frost, correctly pointed out that ‘The Northwest Territory’ is an incorrect reference to that region of the Tri-Territory acquisitions. In all histories of the United States, ‘The Northwest Territory’ was the area that was to become the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and a part of Minnesota. The correct designation should be, ‘Oregon Country’. The second weakness to the proposal was that the site ‘is not in itself a place at which any historic event occurred.’ Because of these ‘weaknesses’ and other bureaucratic obstacles the nomination was vetoed. No attempt to change the wording on the plaque or to militate the other deficiencies in the nomination has to date been attempted.

No battles were fought at the Tri-Territory Site. It is miles from any emigrant trails and even farther from the railroad. It was never a settlement, nor was it a military post or a Native American encampment. Yet, for all that, its importance—and its legacy—are beyond question. It was, and will always remain, the hinge and lynchpin of the American West.

The site lies in Wyoming’s Red Desert, 28 air miles southeast of Farson and 32 air miles northeast of Rock Springs. To reach it requires more 45 miles of travel from Rock Springs, only 10 miles of which is on a paved highway, U.S. Highway 191. The rest is dirt roads, and a wintertime visit is not recommended. In any event—when weather permits—interested travelers can find directions on the Bureau of Land Management website at https://www.blm.gov/visit/tri-territory-site, or use the field-trip suggestion, below.

Editors’ note: This article was funded in part by Rocky Mountain Conservancy, a nonprofit Cooperating Association based in Estes Park, Colo., through book store sales at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper, Wyo. We offer our special thanks.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “Convention of 1818 between the United States and Great Britain.” Department of Political Science, San Diego State University, San Diego, Calif., accessed Oct. 15, 2022 at https://loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1818GB_USConvention.pdf.

- “Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848).” National Archives, Milestone Documents. Archives.gov, accessed Oct. 24, 2022 at https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-guadalupe-hidalgo.

Secondary Sources

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. "Louisiana Purchase." Oct. 6, 2022, accessed Oct. 15, 2022 at https://www.britannica.com/event/Louisiana-Purchase.

- Kessner, Harry J., P.E., P.S. “Tri-Territory Site.” The American Surveyor, June 2015, accessed Nov. 10, 2022 at https://archive.amerisurv.com/PDF/TheAmericanSurveyor_Kessner-TriTerrito....

- Lavender, David S. The Way to the Western Sea: Lewis and Clark Across the Continent. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

- Maycock, Jessica. “Wyoming and U.S. Territory Acquisitions.” Land Surveying Incorporated, June 27, 2018, accessed Dec. 19, 2022 at https://www.lsi-inc.us/wyoming-u-s-territory-acquisitions/.

- Robinson, George Clarence. "James K. Polk." Encyclopedia Britannica, Oct. 29, 2022, accessed Oct. 23, 2022 at https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-K-Polk.

- “Tri-Territory Historic Site.” The Historical Marker Database, accessed Oct. 25, 2022 at https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=96679.

- United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. “Tri-Territory Site,” accessed Oct. 25, 2022 at https://www.blm.gov/visit/tri-territory-site.

Illustrations

- The map of territorial U.S. acquisitions is from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Atlas via Wikipedia, with the location of the Tri-Territory site added by the author. Used with thanks.

- The photos of the Tri-Territory monument and flagpoles and the original plaque are by the author. Used with permission and thanks. The photo of the newer plaque is by Tom Rea.