- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Bells of Balangiga

The Bells of Balangiga

Until the end of 2018, visitors to F.E. Warren Air Force Base would have found a brick memorial in a prominent position on the historic fort’s parade ground. Holding two old bells and an antiquated cannon, rarely visited, the structure honored one of the thousands of forgotten places around the world where young men in the U.S. military suffered and died. This is the story of how these artifacts came to rest in the Cowboy State for nearly 115 years.

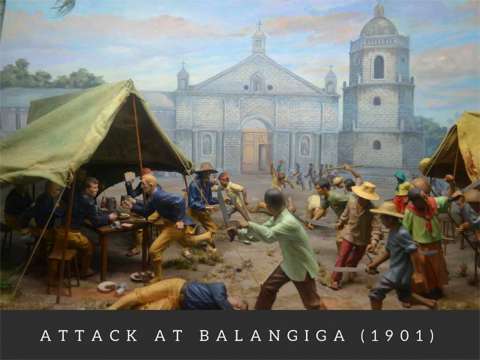

On Sept. 28, 1901, Filipino insurgents, armed only with machete-like bolo knives, attacked the soldiers of Company C, U.S. 9th Infantry, in the town of Balangiga on the island of Samar. The troops, nearly all of them unarmed, were eating Sunday breakfast. Of 74 men in the company, 48 were killed, including all the officers. The rest—all but four of them wounded—managed to escape up the coast in overloaded dugout canoes.

In response, in the most vicious and controversial operation of the U.S. occupation of the Philippines in those years, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps crushed the insurgency in a devastating campaign by the summer of 1902. At the end of the campaign, soldiers of the 11th Infantry brought two church bells from Balangiga back to the base where they were stationed at the time—Fort D.A. Russell outside Cheyenne, now F.E. Warren Air Force Base. A third bell from the Balangiga church, owned by the 9th Infantry, remains at the U.S. Army’s Camp Red Cloud, Uijeongbu, South Korea.

Begiining in the 1990s, Various Filipino groups mounted efforts for the return of all or some of the bells to the Philippines. The return was finallly accomplished in December 2018.

Background

The Philippines—an archipelago of 7,641 islands in the western Pacific--had been a colony of Spain since the 1500s. In the early 1890s, the Filipinos began an insurrection against their Spanish rulers. When the United States went to war with Spain in the spring of 1898, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo and other Filipino leaders believed that they had verbal assurances from American officials that U.S. troops would support their struggle. When the U.S. Navy conquered the Spanish fleet in Manila bay, the insurgents controlled all of the islands except for the city of Manila. The Filipinos turned over 15,000 prisoners to the Americans.

The Americans, however, made a secret deal with the Spanish that the Spaniards would surrender only to the Americans. The U.S. Army kept the Filipino insurgents out of the city. When it became apparent that the United States had no plans to grant immediate independence to the former colony, the insurgents began opposing the Americans. Open war broke out in January 1899. The Philippine Insurrection, as it was popularly known in the United States, continued for three years, from 1899 through 1902, when most Filipino forces surrendered. Other units kept fighting for another decade.

The Filipino opposition was particularly strong on the island of Samar, the third largest island in the archipelago. In fact, Samar represented the second most intense resistance to American governance in the Philippines: The distinction of the most fervent opposition belonged to the Muslim Moros on the southern islands.

In 1898 Samar was remote from the center of American government in Manila, uncharted and unbelievably rugged. Tangled jungle cut by watercourses and ravines constituted most of the interior; small communities of people lived along the coastlines. What little transportation and commerce existed used barotos—logs hollowed out and furnished with bamboo outriggers—as canoes.

As the U.S. Army struggled to establish garrisons and gain control over Samar, a letter was received from Pedro Abayan, presidente of the town of Balangiga, a community of approximately 1,000 residents on the southern end of Samar. Dated Aug. 1, 1901, the letter asked for U.S. troops to protect the town from “savages of the mountains” who were burning his and other adjacent towns and massacring his people. Accordingly, on Aug. 11, 1901, Company C, 9th U.S. Infantry, arrived at Balangiga to establish a garrison for just that purpose.

Previously, however, on May 31, Presidente Abayan had written to Gen. Vincente Lukban, commander of the Filipino insurgents on Samar, advising him: “… after having conferred with the principals of the town of Balangiga about the policy to be pursued with the enemy in case he comes in, that we have agreed to have a fictitious policy with them; that we have agreed … that when the occasion arises, the people will rise up against them.”

Company C was commanded by 29-year-old Capt. Thomas W. Connell, a West Point graduate, combat veteran of San Juan Hill in Cuba during the war with Spain and of the Chinese Expedition of 1900, was a devout Catholic, spoke fluent Spanish and was sympathetic to the Filipino people.

Relationships between Company C and the Filipinos were initially friendly, but in short order they deteriorated. On Aug. 22 two native women reported that they had been sexually assaulted by some of Connell’s soldiers. Their stories were confused and inconsistent, and they failed to identify the culprits from the ranks of Company C. From then on, however, the captain prohibited fraternization between his garrison and the town people.

Most significantly, Connell became increasingly concerned with the sanitary condition of the town. Fearing a cholera outbreak, Connell first asked and then ordered the Filipino citizens to clean up, but got no response. Eventually he ordered those in his command to surround the village men, arrest them and force a number of them into daily sanitation details.

To augment this work force, he accepted an offer from the chief of police to bring in an additional 80 workers from the jungle “to work off their taxes.” These workers were actually trained, disciplined insurgents, skilled in the use of their bolo knives (similar to machetes), recruited by the chief of police to execute a long-planned attack on the American garrison. Insurgents like them were known by the Americans as “bolo men.”

Although Connell had multiple sentries continuously posted and required his men to be armed at all times, he unfortunately permitted his soldiers to eat their meals without their weapons, which remained in their barracks under guard. Unquestionably, the chief of police and insurgents carefully noted this vulnerability.

The attack

At 6:30 a.m. on Saturday, Sept. 28, Company C was at breakfast. Many of the soldiers were distracted by reading a batch of long-overdue mail, which had arrived the night before.

The Filipino chief of police, a “giant in stature and strength,” started the attack when he snatched a Krag rifle out of a soldier’s hands, knocked him down with its butt, then shot and mortally wounded another private nearby. Cries of the attackers rang out across the plaza.

“The tower bells rang out a deafening appeal. [The attackers] yelled as they came towards me,” Pvt. Adolph Gamlin remembered years later, “which was the signal to Filipinos concealed in the church bell-tower to ring the bells for the attack to be made by bolo men hidden in the church during the night to make a rush on the officers. …” Instantaneously, in a perfectly coordinated and planned attack, the American doughboys found themselves assailed from all quarters.

Many of the soldiers, distracted with their mail and news from home, were confused and slow to react. Sgt. George Markley snapped them out of their lethargy with a booming shout, variously recorded as, “They’re in on us, get your rifles, boys!”[1]

With Markley’s battle cry ringing out, the fight for Balangiga was on.[2]

The American encampment occupied various positions around the town’s central plaza. The officers’ quarters, guardroom and aid station were in an abandoned convent next to the Catholic Church of San Lorenzo de Martir, with attached bell tower. On the other side of the town’s plaza, the company barracks, orderly room, commissary, arms room and supply room were located in a two-story masonry tribunal building, in relatively poor repair. The barracks were on the second floor. The tribunal was too small to hold the entire garrison, so two separate squads, commanded by Sgts. George F. Markley and Frank Betron, occupied two elevated native Nipa huts, which had mess benches underneath them. A company mess tent was located behind the tribunal. A flagpole for the American flag had been installed at the center of the plaza.

The Filipinos launched three coordinated mass attacks: one on the armed sentries around the encampment; the second against the officers’ quarters in the convent and the third focused on the unarmed soldiers in the mess tent. Other groups of insurgents tried to keep the soldiers from reaching their weapons in their barracks.

The entire village degenerated into a violent, vicious brawl at close quarters.

Markley, from his central position at the mess tent, saw the entirety of the initial assault. In an interview years later, he recalled, “The sentries were cut down in a flash. One group of natives ran for the barracks where the arms were stacked. Another sped to the priest’s house [sic.,the convent] where the officers lived and sounds of a struggle and suppressed cries only preceded a following stillness that could not be misunderstood. A major, first lieutenant and captain had been killed—hacked to pieces with the fearful bolos.”

All the U.S. troops in the convent were killed in the initial rush.

Musician George A. Meyer related the desperate struggle in the tribunal: “A fearful hand-to-hand struggle ensued, with soldiers and natives in death grips for the possession of rifles and bolos. … I saw Private [Albert B.] Degraffenreid, a great big fellow, standing on a pile of rocks, which he was hurling at the natives, bowling them over like nine pins. We heard shots from the direction of Sergeant Markley’s shack and were later joined by him with a few of the survivors.”

The attack nearly succeeded. However, at the two Nipa huts, the soldiers eating their breakfast were located directly beneath the hut, and one soldier was on guard inside each hut with Krag rifles and ammunition immediately available to him. As a result, American resistance began at these two huts, and rifle fire from them began disrupting the attack. Markley remembered, “I fired 120 rounds of ammunition in thirty minutes, and had to throw away one gun when the lock caught fire.”

Slowly, under the cover of heavy Krag rifle fire, the scattered bands of soldiers gathered together, and their fire drove the attackers into the surrounding jungle. Three officers and 35 enlisted men out of Company C’s original garrison of 74 officers and men had been killed in the initial insurgent attack, a mortality rate of more than 50 percent. All but five of the survivors had been wounded to some degree, with 19 soldiers severely or critically wounded.

Betron was the senior surviving non-commissioned officer, and he assumed command of Company C. Filipinos, during the attack, had captured 52 rifles with 26,000 rounds of ammunition, the majority when they had overrun the first floor of the tribunal building. With the surgeon and his assistant dead, nearly every man wounded and in desperate need of care, and only five men still capable of fighting, Balangiga was untenable. Betron dispatched Meyer and Pvt. Claude Wingo to retrieve the flag from the flagpole, seized five barotos and evacuated the town by using the boats.

The escape

The voyage of the five small barotos proved a terrible ordeal. The Americans were attempting to reach the nearest garrison at Basey on Samar, approximately 25 miles from Balangiga. The insurgents initially launched their own boats to overtake the Americans, but rifle fire drove them off. Instead, the insurgents followed along the coastline, marking their progress with signal fires and conch shell blasts, hoping the canoes would be forced ashore so they could be attacked and overwhelmed.

The canoes, never intended for anything more than local fishing, were drastically overloaded. The American soldiers were unfamiliar with them, and most of the badly wounded men could not assist. All five barotos slowly began to sink, and their progress slowed to a crawl.

Eventually the smallest baroto, manned by Pvts. Claude Wingo and Charles Powers and towed by the canoe of Betron, began to founder. Wingo severed the tow cable, telling Betron, “I’ll have a better chance paddling my own canoe.” Powers’ body was later found ashore. He had drowned. Wingo was never seen or heard from again.

Soon a boat commanded by Pvt. Bertholf began to suffer a similar fate. With five men on board, it was driven ashore about midnight. Two badly wounded men, Pvts. Behrer and Litto Armani, were carefully concealed in rocks along the shore while the other three men attempted to locate another canoe. When they returned, the two wounded men had been cut to pieces. When the three remaining soldiers finally located a canoe so old and decrepit that it had been abandoned by the natives, they set out again, but they never did reach Basey. Eventually, helpless and in desperate straits, they were picked up by a U.S. Naval vessel.

About dawn, the rest of the men straggled into Basey, feebly and desperately crying out to the sentry, “Help, for Christ’s sake, Help!”

Immediately, a column was dispatched to Balangiga. Capt. Edwin V. Bookmiller, commanding Company G of the 9th Infantry at Basey, led 55 men onboard the SSPittsburg, an armed coastal steamer, accompanied by those few survivors of Company C who still remained capable of duty. Upon landing, Bertholf recalled, “… they found the buildings burning and the dead horribly mutilated.”

During Company G’s advance into the town, 20 insurgents had been captured. While members of Company G secured the town, carefully buried the Americans and salvaged what equipment they could, Bookmiller was asked what to do with the prisoners. He replied, “That’s Company C’s business.” A harsh volley of Krag rifle fire provided the response of the survivors of Company C.

Bookmiller’s Company G did not initially re-establish the garrison at Balangiga, but in short order the U.S. Army launched a determined effort to eradicate the insurgency on Samar. This campaign proved to be brutal and vicious, and two senior officers were court-martialed for excessive violence and brutality during the campaign. Gen. Jacob Hurd Smith ordered American troops to kill everyone on Samar over 10 years old. At least one officer refused the order and eventually, the Army court-martialed Smith for it; he was found guilty, and his career ended.

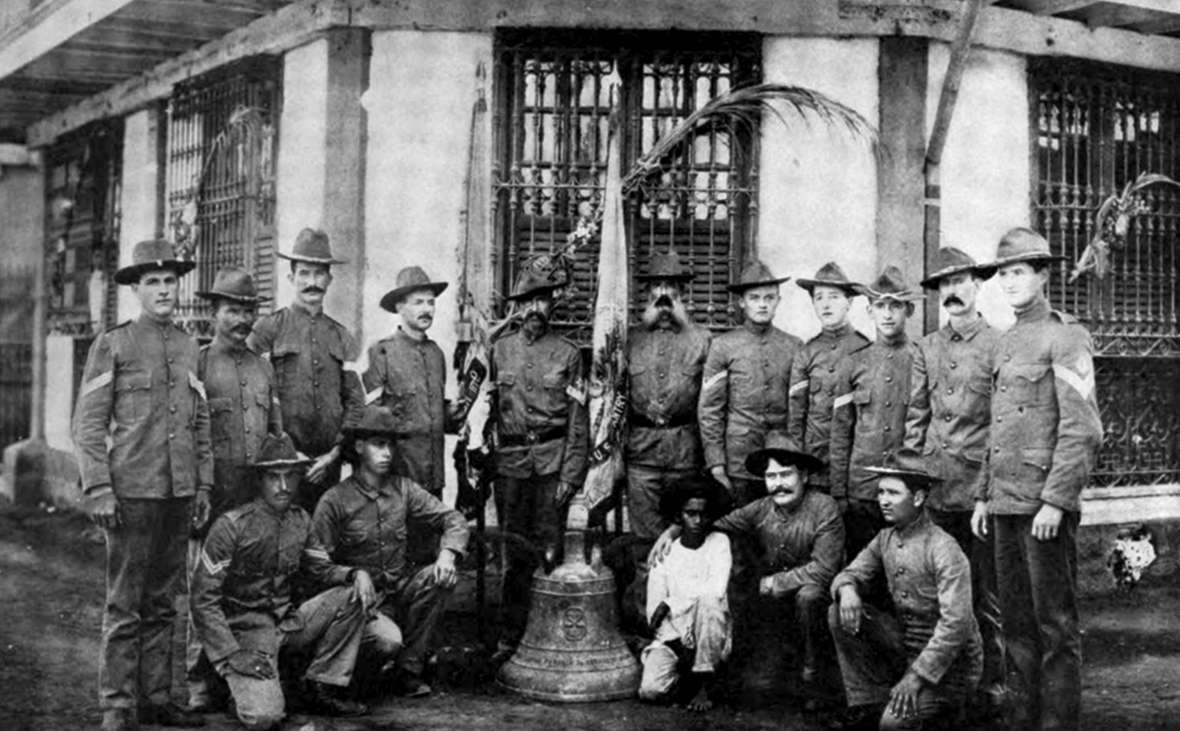

In support of the efforts to subjugate and punish Samar, meanwhile, a large two-company garrison would again be installed in Balangiga, consisting of Companies K and L, 11th Infantry Regiment. Upon their arrival in what remained of the community, the 11th Infantry secured the two bells from the church bell tower that had been used to signal the Sept. 28 attack. An older cannon on the plaza was also seized. The soldiers saw the two bells, which had played a critical role in the surprise insurgent attack, as legitimate trophies of war.

By the summer of 1902, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps, in a vicious and months-long campaign, had crushed the Samar insurgency. Veterans of the 11th U.S. Infantry were ordered home in late 1903. On March 23, 1904, they arrived at their new garrison, Fort D.A. Russell at Cheyenne, Wyo. They were accompanied by their war trophies—two of the bells and the cannon. On May 16, 1905, the Cheyenne Daily Leaderreported that a monument had been established on the parade ground near the flagpole: “… to include the famous bell which gave the signal for the massacre of a whole company.”[3]

In February 1913, the 11th Infantry departed Fort D.A. Russell for deployment on the Mexican border. The regiment never returned to Wyoming. For well over a century now, the bells have remained on the parade ground at Fort D.A. Russell in Wyoming, even as that garrison was transformed from an active army base to a World War II quartermaster training center, to eventually become today’s F.E. Warren Air Force Base, a U.S. intercontinental ballistic missile headquarters facility.

Col. Robert J. Hill, commanding officer of the 90th Strategic Missile Wing, decided in 1967 that the bells deserved a better presentation. He had a curved red brick wall with appropriate commemoration constructed in Trophy Park at the Air Force base, which remains to this day. The memorial has since served as an integral feature upon the historic parade ground, dominating the landscape.

The Balangiga war trophies rested quietly at Fort D.A. Russell and later F.E. Warren Air Force Base for 90 years, through the 1980s, without comment or controversy.

The return of the bells

In 1993, President Bill Clinton made a state visit to the Republic of the Philippines. At that meeting, Philippine President Fidel V. Ramos formally requested that the Bells of Balangiga be returned to his nation. In addition, the Philippine government, the Catholic Bishop’s Conference of the Philippines and other groups pressed the U.S. government to return the bells. The U.S. Air Force retained legal title to the bells, which could only be altered through legislation passed by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by the president of the United States.

Current Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte demanded the bells’ return in 2017 in his state of the nation address, though he did not raise the issue four months later in a meeting with President Donald Trump.

But in the summer of 2018, according to Wyoming U.S. Senator Mike Enzi spokesman Max D’Onofrio, the Department of Defense sent a letter of intent to Congress announcing its plan to return the bells. In August of that year, Wyoming’s congressional delegation issued a statement opposing the plan.

The Trump administration by that time appears to have determined, however, that returning the bells would be good for relations with the island nation. That concern overrode opposition from veterans’ groups, the Wyoming delegation and Wyoming Gov. Matt Mead.

The return of the bells was finally authorized by a rider attached to DOD funding legislation. It required the secretary of defense to validate that no security interests were involved, and to work with the veterans community. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis did sign the authorization, but the veterans community was never notified or involved as required by the law.

On Nov. 14, 2018, Mattis and Philippines Ambassador to the U.S., H.E. Jose Manuel G. Romualdez, visited Warren Air Force Base. At a gathering of “a couple of hundred air force officers, personnel and family members,” according to the Associated Press, Mattis announced the start of a process to return the bells to the Philippines. The Wyoming delegation at the time issued a second statement opposing the move.

The bells were returned in December 2018 aboard a U.S. military plane, the Spirit of MacArthur, named after Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Allied forces whose forces drove the Japanese out of the Philippines in World War II.

Summarizing what happened, Enzi spokesman D’Onofrio said in January 2019 that the DOD “sent a letter of intent to Congress, and then [the agency] went ahead and removed the bells. Our opposition remained, but Mattis made it happen.”

Resources

Sources

- Adams, Gerald M. The Bells of Balangiga.Cheyenne, Wyo.: Lagumo Corp., 1998.

- _______________. “The F.E. Warren Air Force Base War Trophies from Balangiga, Philippine Islands.” Annals of Wyoming59, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 29-37. Accessed May 22, 2018, at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom59121987wyom.

- “Balangiga Bells.” Wikipedia. Accessed March 21, 2018, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balangiga_bells.

- Bruno, Thomas A. “The Violent End of Insurgency on Samar, 1901-1902.” Army History(Spring 2011): 30-46. Accessed Dec. 29, 2017, at: https://history.army.mil/armyhistory/AH79(W)r.pdf.

- D’Onofrio, Max. Telephone interview with WyoHistory.org Editor Tom Rea, Jan. 4, 2019.

- Drake, Kerry. “The Full Story of the Bells of Balangiga.” WyoFile. Aug. 21, 2018. Accessed Dec. 17, 2018, at https://www.wyofile.com/?s=Bells+of+Balangiga.

- Gruver, Mead. “Mattis: War-trophy bells' return to help US, Philippine ties.” Associated Press, Nov. 15, 2018. Accessed Jan. 4, 2019 at https://www.apnews.com/4b056b447c5740279842612740973914.

- Holden, William N. “The Samar Counterinsurgency Campaign of 1899-1902: Lessons Worth Learning?” Asian Culture and History6, no. 1 (2014): 15- 30. Accessed Dec. 29, 2017, at: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ach/article/view/29381.

- McCarthy, Julie. “U.S. Returns Balangiga Church Bells to the Philippines After More Than a Century.” Dec. 11, 2018. National Public Radio. Accessed Dec. 17, 2018, at https://www.npr.org/2018/12/11/675505073/after-117-years-balangiga-bells-will-be-returned-to-the-philippines.

- Randall, Doug. “Wyoming Delegation Speaks Out Against Plan to Remove Bells,” KGAB. Aug. 14, 2018. Accessed Dec. 17, 2018, at http://kgab.com/wyoming-delegation-speaks-out-against-plan-to-remove-bells/.

- “Philippine-American War.” Wikipedia. Accessed March 21, 2018 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippine–American_War.

- Schott, Joseph L. The Ordeal of Samar.Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1964.

- Stewart, 1st Lt. Elam L. “The Massacre of Balangiga.” Infantry Journal30, no. 4 (April 1927): 407-414. Collections of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.

- Stewart, Phil. “U.S. Returns 'Bells of Balangiga' to Philippines a Century After Clash.” Reuters news agency, via U.S. News & World Report, Nov. 14, 2018. Accessed Jan. 4, 2019 at https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2018-11-14/us-returns-bells-of-balangiga-to-philippines-a-century-after-clash.

- Taylor, James O. The Massacre of Balangiga, Being an Authentic Account by Several of the Few Survivors.Joplin, Mo.: McCarn Printing Company, 1931. Collections of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.

Illustrations

- The US Air Force photo of the Bells of Balangiga is from wyomingnews.com. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the Manila street scene is from the author’s collection. Used with permission and thanks.

- The diorama of the attack is an exhibit at the Ayala Museum, Manila, Philippines. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the Balangiga survivors and the 1920s photo of the bells are from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Secretary Mattis, Ambassador Romualdez and the officers at Warren AFB in November 2018 is by Blaine McCartney of the Wyoming Tribune Eagle, via the Associated Press. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the bells being unloaded in Manila is by Julie McCarthy of National Public Radio. Used with thanks.

[1] Sgt. Markley himself remembered, “I yelled out ‘Get your rifles, boys’ or something to that effect.” Other soldiers recalled him saying, “They’re in on us, get your rifles, boys!”

[2] Numerous modern revisionist historians have questioned whether the bells in the Balangiga Church’s bell tower actually signaled the attack. All 10 Company C survivor accounts consistently recorded that either a bell or bells in the church rang to coordinate the launch of the Filipino insurgent attack.

[3] “Fort Russell News Notes.” Cheyenne Daily Leader,May 16, 1905, 3. Accessed Dec. 29, 2017, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov/.