- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Reverend John Roberts, Missionary To The Ea...

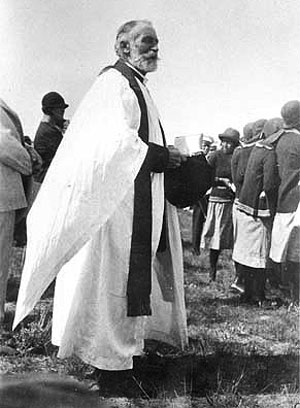

The Reverend John Roberts, Missionary to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes

In 1868, a treaty was signed with the Shoshone people establishing for them a reservation in the west central part of Wyoming Territory. In 1878, they would be joined by their longtime adversaries the Arapaho on what would become the Wind River Indian Reservation.

The following year, the new American president Ulysses S. Grant made a surprising move by putting religious denominations in charge of overseeing new reservations throughout the West. On April 10, 1869, “Grant’s Peace Policy” went into effect. It was also known as the “Quaker Policy” because the Quakers influenced its enactment. This new policy rewarded those tribes that settled down, took up agriculture and stayed out of the way of encroaching white settlements. Indian people who continued to live away from the reservations would be considered “hostile.” Most importantly, the policy stated, “The church groups were to aid in the intellectual, moral and religious culture and thus assist in the humanity and benevolence which the peace policy meant.”

In Wyoming, The Episcopal Church received responsibility for the new Shoshone Indian Reservation. The church was never properly prepared to look after the 1,500 Shoshones who would live there. In the 1870s, the church was poor and lacked clergy. It wasn’t until 1883 that the first missionary clergyman was sent to the reservation.

John Roberts was born on March 31, 1853, in Wales. His interest was serving the church in the missionary field, and he was sent to Nassau in the Bahama Islands. It was there that he was ordained to the priesthood. However, Roberts yearned for a greater challenge. His opportunity came when he met Episcopal Bishop John F. Spalding who served Colorado and Wyoming. Spalding assigned him to work with the Shoshone in Wyoming.

Roberts’s trip there was a memorable one. He took the train to Green River and then traveled the last 150 miles by stage. . This journey came in the midst of a blizzard with temperatures nearing 60 degrees below zero. The journey took eight days; on February 10, 1883, he finally arrived at his new home. While serving in the Bahamas, Roberts had become engaged to a young church organist named Laura Brown. They kept up their relationship by exchanging letters until she was able to come to Wyoming. She arrived by train in Rawlins on December 24, 1884. Roberts met her there. They were married on Christmas Day at Saint Thomas Episcopal Church. They would raise five children during their years together.

At Fort Washakie, on the reservation, Roberts quickly went to work serving the people. He became the first superintendent of the government school. School attendance was compulsory for Indian children. Many attended against their will. In 1885, Roberts established The Church of the Redeemer that would serve the Shoshone people and other area residents.

The reservation wasn’t the only place where an Episcopal presence was needed. Roberts proceeded to organize congregations in Lander, Dubois, Crowheart, Riverton, Thermopolis, Milford, Hudson and Shoshoni. All but the latter three have active congregations at the present time. “Father Roberts,” as he became known, spent countless hours visiting those fledgling churches, traveling by horseback in all kinds of weather. He officiated at numerous baptisms, communion services, weddings and burials.

Roberts also became a close personal friend of Chief Washakie of the Shoshone. Washakie, who was in his early 80s when Roberts arrived, was seen as a fair but autocratic leader. One legendary story was told about this relationship. The chief’s son, Jim Washakie, was shot and killed in 1885 by a white man in an argument over a liquor purchase. When Chief Washakie heard of this, he became distraught and vowed to kill every white man he saw until he himself was dead. When Roberts heard of this, he visited the chief in an attempt to talk him out of it and the clergyman offered his own life instead. Washakie reconsidered and said, “I do not want your life. But I want to know what it is that gives you more courage than I have.” Roberts used the occasion to talk about his personal faith and converted Washakie to Christianity.

While this story says much about the character of both men, it was probably not true. The Roberts family tells a different story. Roberts indeed paid a visit to the chief after the incident. But Washakie’s comment was much different. Instead, he stated, “The white man did not kill my son. Whiskey killed him.”

Roberts saw the need for a Christian school on the reservation. The government school served mostly boys, and he felt it was important to educate the girls a well. This became possible in 1887 when Chief Washakie made a personal gift of 160 acres as a site for a new school. Washakie valued Roberts’s presence, and the chief felt it was important for his people to receive an education so that they would be prepared to live within the encroaching white society. The Shoshone Episcopal Mission School, later referred to as “Roberts’s Mission,” began operations in 1889 and served numerous reservation girls until it closed in 1945. The donated site on Trout Creek was long considered sacred ground by the Shoshone.

The school was built with the assistance of Episcopal Bishop Ethelbert Talbot, who raised funds for the complex. The bishop thought very highly of the Reverend Roberts and his dedication to Indian ministry. He once offered Roberts the opportunity to have a more prestigious position, but Roberts declined, saying, “Thank you, Bishop, but I hope you will never take me away from my Indians. I prefer to spend my life here among my adopted people.”

The Northern Arapaho tribe, led by Chief Black Coal, was allowed to settle on the Shoshone reservation in 1878. Roberts did not hesitate to expand his ministry to the Arapaho. Saint Michael’s Mission was established at the present site of Ethete in 1919. A church, a school and several other buildings were constructed. The log church was named “Our Father’s House.” The mission itself was named after Michael White Hawk, an Arapaho catechist who assisted Roberts in translating the Gospel of Luke into Arapaho.

In 1884, the Reverend Sherman Coolidge was assigned to the reservation to assist Roberts in his ministry. Coolidge was a full-blooded Arapaho priest who had been separated from the tribe as a young boy and raised by Captain Coolidge from the military post. He was educated in Minnesota and then sent back to his people. Both Roberts and Coolidge left enduring legacies through their work with the Arapaho.

The Reverend John Roberts also officiated at two prominent funerals. The first occurred on April 10, 1884. A woman known as “Wad-ze-wipe,” mother of Baptiste and stepmother of Bazil, died at about age 100. According to Shoshone tradition and early Wyoming historian Grace Raymond Hebard, this was Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Many modern scholars argue that Sacagawea died shortly after her historic journey and is buried in what’s now South Dakota. Roberts believed that “Wad-ze-wipe” was the true Sacagawea and recorded her as such in the church burial records.

The second funeral was that of the venerable Washakie, on February 22, 1900. Washakie, said to be 102, was buried with full military honors at the post cemetery. He had served the United States Army for many years as a scout. The Reverend Coolidge assisted Roberts in the service. In 1897, before his death, Chief Washakie summoned Roberts to his home for a visit. There, on January 25, Washakie officially became a Christian through baptism at the age of 97. He became active in this faith for his remaining three years and encouraged other Shoshones to become Christians as well.

Roberts served his people for as long as he was able. He served as became a bridge for Indian people with the white culture that surrounded the reservation. His style could best be described as “loving paternalism.” In his later years, he suffered from blindness. It was said he could identify visitors to his log home by the sound of their footsteps on a creaking floor. He died on January 22, 1949, and is buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Lander. His Wyoming ministry lasted 66 years.

Resources

Primary sources

- Hebard, Grace Raymond collection, Chief Washakie files, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

- Talbot, Ethelbert. My People of the Plains. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1906, 14.

Secondary sources

- Hebard, Grace. Washakie: Chief of the Shoshones. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995, 160. First published 1930.

- Kingsbury, George. A History of Dakota Territory. Chicago, S.J. Clarke Company, 1915, Vol. I, 783-84.

- Markley, Elinor R. and Beatrice Crofts. Walk softly, this is God's country: sixty-six years on the Wind River Indian Reservation : compiled from the letters and journals of the Rev. John Roberts, 1883-1949. Lander: Mortimore Press, 1977, 5, 125. Markley and Crofts support Hebard (above) in her findings.

- Urbanek, Mae. Chief Washakie. Boulder, Colo.: Johnson Publishing Co., 1971, 113-14.

- Urbanek relied heavily on the Grace Hebard files on Chief Washakie now at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming.

Illustration

- The undated photo of the Rev. Roberts is from the Wyoming State Archives, negative number 18894A, used with thanks; clothing on the people in the background suggests a date around 1930.