- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Estelle Reel, First Woman Elected To Statewide ...

Estelle Reel, First Woman Elected to Statewide Office in Wyoming

Educator Estelle Reel fought hard to obtain the Republican nomination for Wyoming superintendent of public instruction in 1894, after which she became the first woman Wyoming voters ever elected to a statewide office. At that time, Wyoming and Colorado were the only states where women had full voting rights. Wyoming women had been voting since 1869; Colorado women exercised the franchise for the first time that year.

But a number of states by the early 1890s allowed women to vote in some elections--usually school elections, and sometimes municipal ones. According to at least one contemporary account, as many as 21 states at that time allowed women at least partial voting rights. So it was that one of them, North Dakota, was the first state in the nation ever to elect a woman to statewide office--Laura Eisenhuth, who won the office of superintendent of public instruction in the fall of 1892.

As for Reel, she performed so well as Wyoming superintendent that after two years in the job, she was being touted in the press as a possible candidate for governor.

She quickly tried to squash such speculation. “The idea of a woman running for governor of the state of Wyoming is not worthy of serious consideration,” she wrote to the editor of the New York Sun.

Reel's election had already cemented her place in the history of the woman suffrage movement, but her response that a woman could not possibly be a governor wasn't well received by some of the more radical members who wanted no limits on women's aspirations.

She wasn't done making history, however. When she left her Wyoming office after three years to become the national superintendent of Indian schools, Reel became the first woman to be confirmed for a federal office by the Senate. But as confounding as it was for her contemporaries, the fact that Wyoming's most successful woman politician of her time wouldn't even consider running for governor was consistent with her lifelong views on the limited role women should play in government.

County and state politics

Reel was born in Illinois in 1862, and came to Cheyenne, Wyo., in 1886 after being educated in Boston, St. Louis and Chicago. Her employment as a teacher in Cheyenne was threatened by criticism from some school board members, but she emphatically let them know that they had no right to dictate where she went to church, bought her clothes or boarded.

The public defense of herself played well with voters, who elected her school superintendent of Laramie County, where Cheyenne is located, by a wide margin in 1890. She was re-elected two years later, and then set her sights on becoming the state superintendent.

In Wyoming, the state superintendent of public instruction is one of five executive officers elected by voters statewide; the other four are governor, secretary of state, state auditor and state treasurer. In addition to their other duties, the officials serve as members of five-person boards that act under different names according to the different areas of oversight. The state Land Board, for example, oversees revenues from and management of state lands, and the state Board of Charities and Reform in those years was in charge of the state prison and the state mental hospital.

The 1894 Wyoming Republican caucus in Casper was a contentious affair, as party leaders sought to quell rebellion from party members who thought too much power was in the hands of Cheyenne politicians. GOP delegates from Laramie County decided to back only local candidates for state auditor and state treasurer, and it seemed that Reel's attempt to earn the party's nomination for schools chief would give way to Therese Jenkins, a school superintendent in another county who was active in the women's suffrage movement.

A statewide campaign

Undeterred, Reel was instead nominated for the state office by Uinta County, where her brother, Alexander “Heck” Reel, was a well-known Democrat and rancher who later served as Cheyenne's mayor during his sister's tenure as superintendent, and she secured the Republican Party's blessing. She hit the campaign trail hard, traveling throughout the 4-year-old state by railroad, stagecoach, ranch wagon and horseback. She even went down into a mineshaft in Rock Springs to garner votes.

Reel was an attractive woman who sported a pompadour hairstyle with a bun, popular in her day, and she charmed audiences with a short stump speech that focused on the state's great potential for economic growth. Critics charged that a woman couldn't handle the superintendent's complex duties as secretary of the state land board, which came with the superintendent's position. Reel countered that any woman who had studied the issues—as she did—could do the job as well as any man.

The Rocket-Miner in Rock Springs—home to Democratic state superintendent candidate A.J. Matthews—favored Reel, calling her “one of the best educated and most brilliant women in the state.” The newspaper added, “It behooves every man and woman in the state to vote for her.”

But support for her was not universal. As Republicans had feared, their opponents tried to capitalize on the perceived anti-Cheyenne feelings of the electorate. The Carbon County Journal warned, “should she unfortunately be elected … she will be seen as putty in the hands of the Cheyenne ring. The only safe thing to do is defeat her with the rest of the gang ticket.”

Reel was the only Republican candidate for statewide office in 1894 to carry every county in Wyoming. In defeat, her opponents tried to minimize her victory by claiming she won because she enclosed her picture in “perfumed letters” sent to lonely cowboys, who were supposedly so smitten they rode more than 100 miles to vote for her, and waved guns in the faces of those who dared to vote against her.

None of this was true, but the reports were later circulated by the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times, and accepted as fact by many. Reel detested the story and denied it at every opportunity. Attempting to set the record straight when an eastern journalist asked about how her picture influenced male voters, Reel said that the Chicago editor had been “misled by a wild-west story. … In common with other candidates on both state tickets my picture was printed in state newspapers, on campaign literature, etc., but it had no more perceptible effect on the voters than the picture of the other candidates.”

State superintendent of public instruction

During the Feb. 7, 1895 inauguration of the GOP slate of state officials, the Cheyenne Sun Leader reported that Reel was a big hit with the audience. “As she faced the crowd a wonderful cheer went up,” the paper stated. “There had been plenty of applause before, but Miss Reel received an absolute ovation.”

Once in office, Reel quickly put to rest the notion that she couldn't handle complex land issues. The amount of money available for schools depended on how much was collected from ranchers who bought or leased what was available among the 3 million acres of state public lands set aside as school sections, with revenues from them to benefit schools. Within months of taking office, Reel had made changes to the state's system of investing the interest from these funds, a move credited with significantly increasing revenue for the schools.

Her success dealing with other educational issues was mixed. She supported a standardized curriculum that would put students in rural schools on an equal level with their city counterparts. In 1897, Reel wrote a pamphlet, the “Outline Course of Study for Wyoming Public Schools,” that she intended to serve as a guideline for teachers. It sold out its initial run, but there wasn't any money in her budget to print more.

Reel supported the free distribution of textbooks to Wyoming students, a matter that had been controversial since territorial days because of the expense. Unfortunately, a law authorizing free textbooks didn't pass the Legislature until 1899, after she left office.

The superintendent also tackled the issue of teacher certification, which was handled differently by school districts throughout the state. There was no standardized examination for teachers, who had to be retested every year to keep their jobs. Certificates were also only good in the county where they were obtained. Again, no progress was made during her tenure, and statewide certification and standardized tests weren't approved until 1899.

Reel was honest—sometimes brutally so—when people wanting to teach in Wyoming wrote to her for help. “If you should decide to come West I think you could do better in Portland, Oregon, than any other place in the West that I know of at the present time,” she wrote to Alice Higgins, an Illinois job seeker. “I spent a week there last summer and found the conditions, work, wages and expenses better for teachers than any place I have ever been.”

She could afford to send people to other destinations because Wyoming had a surplus of people who wanted to be teachers.

As superintendent, Reel was stymied by a state Legislature that put education on the back burner as lawmakers funded other priorities. She tried to maintain the money that the state gave her office, but it wasn't an easy task. As she wrote to a friend, Mrs. Jennings, during the February 1895 legislative session, “The prospects are that my contingent fund will be almost all taken away from me, as the politicians seem determined to make my office of as little importance as possible.”

Known for her boundless energy on the campaign trail, once in office Reel began to complain that she was exhausted. “The work of the campaign, of the inauguration, and of a new position have almost prostrated me, and I am very anxiously looking forward to the time when I can take a vacation, be it ever so brief,” she wrote to one friend in Sheridan. To another friend named “Billy,” she noted her days were spent in “endless meetings of land boards, dreary sittings of the State Board of Charities and Reform, wearisome visits to the insane asylums, hospitals, penitentiaries, etc.”

Her steady workload made taking a break impossible. She was forced to cancel a vacation to Chicago because the lone secretary in her office became ill. In a letter to a friend, Hobart Martin, she plaintively wrote, “I am very tired of the kind of life I lead, but it is my bread. I've not had much butter.”

National superintendent of Indian schools

Her complaints about her workload may make it seem logical that she applied for another job three years into her term, when she successfully parlayed her work as Wyoming campaign coordinator for President William McKinley into a federal appointment as national superintendent of Indian schools. Reel –who had earned an annual salary of $2,000 as Wyoming's school superintendent—raised eyebrows when she attended McKinley's inauguration wearing a $1,000 Parisian gown and a $50 hat. In her new federal position, Reel's salary was $3,000 per year.

However, the job turned out to be even more taxing than her days in Wyoming. Based in Washington, D.C., she nevertheless spent 17 of her first 26 months in the field, traveling more than 41,000 miles to visit 49 Indian schools. About 2,000 miles of those travels were by wagon, packhorse or on foot. She was in charge of 250 Indian schools in the U.S., with a combined enrollment of about 20,000 students, and administered a budget of $3 million.

Like many officials in her time, Reel considered Indians to be "a lesser race," inferior to whites in both physiological and intellectual development, which she believed limited what they could learn and the tasks they could perform. She wrote a textbook, “A Course of Study for the Indian Schools of the United States—Industrial and Literary" that focused on the "dignity of labor," which was one of her favorite phrases. Reel thought Indian students who were going to be servants or agricultural laborers required a practical education that didn't raise their standards or expectations to what she believed were unreasonable levels.

While the superintendent did not give Indians any credit for being creative—she told the New York Mail in 1899 they were merely "wonderful imitators”—Reel recognized the skills of Indian women in the fields of basketry, sewing, netting, reed work and weaving and their importance to the Indians' economy. White intervention was considered necessary to revive and preserve these skills. “The basketry as woven by Indians for generations past is fast becoming a lost art and must be revived by the children of the present generation,” Reel wrote.

At the same time, federal policymakers and reformers believed that allotting land to Indians would be the cure-all for transforming and civilizing Indian people. Allotment, though, was also the key process in "freeing" lands from tribal ownership and often, eventually, from individual Indian occupancy and ownership as well. After allotments were made, "surplus" lands were opened to non-Indians for sale and/or homesteading, and individual allotments were taken from Indian ownership through a variety of coercions, frauds and chicaneries, as well as some Indians' desire to convert allotments to cash.

Reel had personal connections to western landowners and lessors, plus her experience as Wyoming's registrar of lands, which has raised questions about her role as a possible facilitator of leases and land transfers. On a 1901 trip to the Northwest, she noted many Indians "are very anxious to have their land allotted." After inspecting a school at Siletz, Ore., Reel reported that nearby white neighbors were excellent role models for Indians, and she proposed Siletz serve as a national model where white settlers "cleared the deceased Indians' lands, [so] more speedy progress might be made."

Despite its demands, Reel stayed with the federal job until she resigned in 1910 to marry Cort Meyer, a Toppenish, Wash., rancher and farmer. She had already been out of Wyoming for many years, and her move to Washington state from the nation's capital removed her place in Wyoming's history even further from the public's memory.

“By education, culture, courage, executive ability and powers of endurance she made herself a leader in every field of action she entered,” Wyoming State Historian Frances Beard wrote in 1933.

Reel never again ran for public office, and she died in 1959 at the age of 97.

Legacy

Throughout her career, Reel's achievements as a pioneering woman elected official made her highly sought by others who wanted advice about how to spur the suffrage movement. She spoke her mind, which often wasn't what other women wanted to hear.

Reel believed in the ability of females to perform well in certain fields, notably education and clerical work. But as long as they were able to hold these positions and to receive the same pay as men for equal work, she had told the New York Sun in the 1896 interview, women “will be well satisfied. They will not attempt to encroach upon offices which should always be filled by men, one of which is the Governorship.”

She supported women's right to vote in newspaper articles she penned while serving as Wyoming's superintendent, arguing that as a rule, they were “more intelligent voters than the majority of the men.” But she attributed the success of women's suffrage in Wyoming to the fact that women in the state “have not asked too much at any time of the male voters.”

“[Women] were extremely modest in their requests for preferment and power,” she wrote of Wyoming women in a letter to a St. Louis, Mo. woman, Ella Buie, in April 1896. “They essayed no radical reforms and did what they could in politics and legislation in a quite unobtrusive manner.”

She advised her correspondent that women in Missouri shouldn't seek universal suffrage, but “first get the privilege of voting in school elections,” then obtain a voice in municipal affairs. Suffrage in county, state and national elections “will follow in due time,” Reel predicted.

Reel may have been reticent about pushing for women's suffrage too fast, lest men be offended, but she was no shrinking violet toward males concerning other matters. During a return to Wyoming as head of Indian education, she noted in her journal that a trip to Fort Washakie became a nightmare when the driver of her coach began whipping and swearing at his exhausted team of horses.

“I could not endure seeing the horses abused and told the driver to stop beating them, but he was not inclined to listen to me, and I fiercely turned upon him and threatened to shoot him dead in an instant, and he turned about ten shades redder than his hair and thought some of jumping off the box,” she wrote.

“My companion begged me not to shoot the driver,” she added, “and I finally consented not to, if he behaved himself the rest of the trip.”

Resources

Primary Sources

- Estelle Reel papers (MS120) relating to her job as National Superintendent of Indian Schools, Eastern Washington State Historical Society/Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, Spokane, Wash.

- Estelle Reel Meyer Collection: Scrapbooks; NEA 1896-1897; Campaign 1894-1895 and 1896-1897. Wyoming State Archives.

- Conner, Eliza Archard. “Woman’s World in Paragraphs: Women Are Marching on Toward Liberty and Citizenship.” Cheyenne Daily Leader, March 15, 1893, p. 4, col. 5. Accessed Dec. 1, 2014 via Wyoming Newspapers at http://newspapers.wyo.gov/.

Secondary Sources

- Beard, Frances B., ed. Wyoming: From Territorial Days to the Present. Chicago: American Historical Society Inc., 1933, 513.

- Bohl, Sarah R. “Wyoming's Estelle Reel: The First Woman Elected to a Statewide Office in America.” Annals of Wyoming 75, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 22-35.

- Hewes, Dorothy W. “Fleshing Out the Tale of Estelle Reel” Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1985.

- Hutchinson, Elizabeth. “The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism and Transculturation in American Art, 1890-1915,” Duke University Press, 2009.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. “Estelle Reel, Superintendent of Indian Schools, 1898-1910: Politics, Curriculum and Land. Journal of American Indian Education 35:3 ( May 1996). Accessed Dec. 1, 2014 at http://jaie.asu.edu/v35/V35S3es.htm.

- Van Pelt, Lori. Capital Characters of Old Cheyenne. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press, 2006, 151-156.

- ___________. “Estelle Reel: Early Educator and Politician.” Wyoming Rural Electric News, November 2007, 10-12.

- Wefald, Susan. "Breaking an 1889 Glass Ceiling: Laura Eisenhuth, First Woman Elected to Statewide Office in the United States." North Dakota History – Journal of the Northern Plains, Volume 79.1, 13-25.

- Wyoming Tales and Trails. “Lincoln County Photos.” Accessed Dec. 19, 2013, at http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/afton2.html.

Illustrations

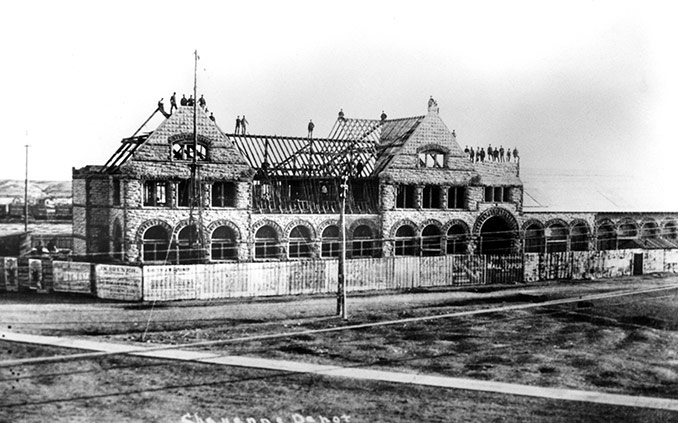

- All five photos are from the Wyoming State Archives, used with permission and thanks. Central School was located at the 100 block of West 20th in Cheyenne.

For Further Reading and Research

- The Wyoming State Archives has two boxes of material in its Estelle Reel Meyer Collection, number H60-110. Items include various scrapbooks, journals, travel guides and recipes. The bulk of the collection focuses on her time spent as Wyoming's superintendent of public instruction, but it also has scrapbooks and other printed material from her 12 years as the national superintendent of Indian schools. For more information on the archives, see the field trip listing below.