William Henry Jackson’s Long Career

By Rebecca Hein

William Henry Jackson’s Lens: How Yellowstone’s Famous Photographer Captured the American West, by Tim McNeese. The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., Lanham, Maryland, 2023, 275 pages. $31.95 hardback.

William Henry Jackson left Vermont in 1866 at age 23 to travel west as a bullwhacker. He had to endure a monotonous diet that eventually made him sick, watch oxen die of exhaustion and see one of his fellow teamsters killed by lightning near Independence Rock. This was the beginning of his long, active career centered on the American west.

Jackson’s early training in drawing and painting began to pay when he was about 13 and discovered that people would hire his services. He was soon retouching and coloring photos for professional photographers, eventually switching to photography as his primary occupation.

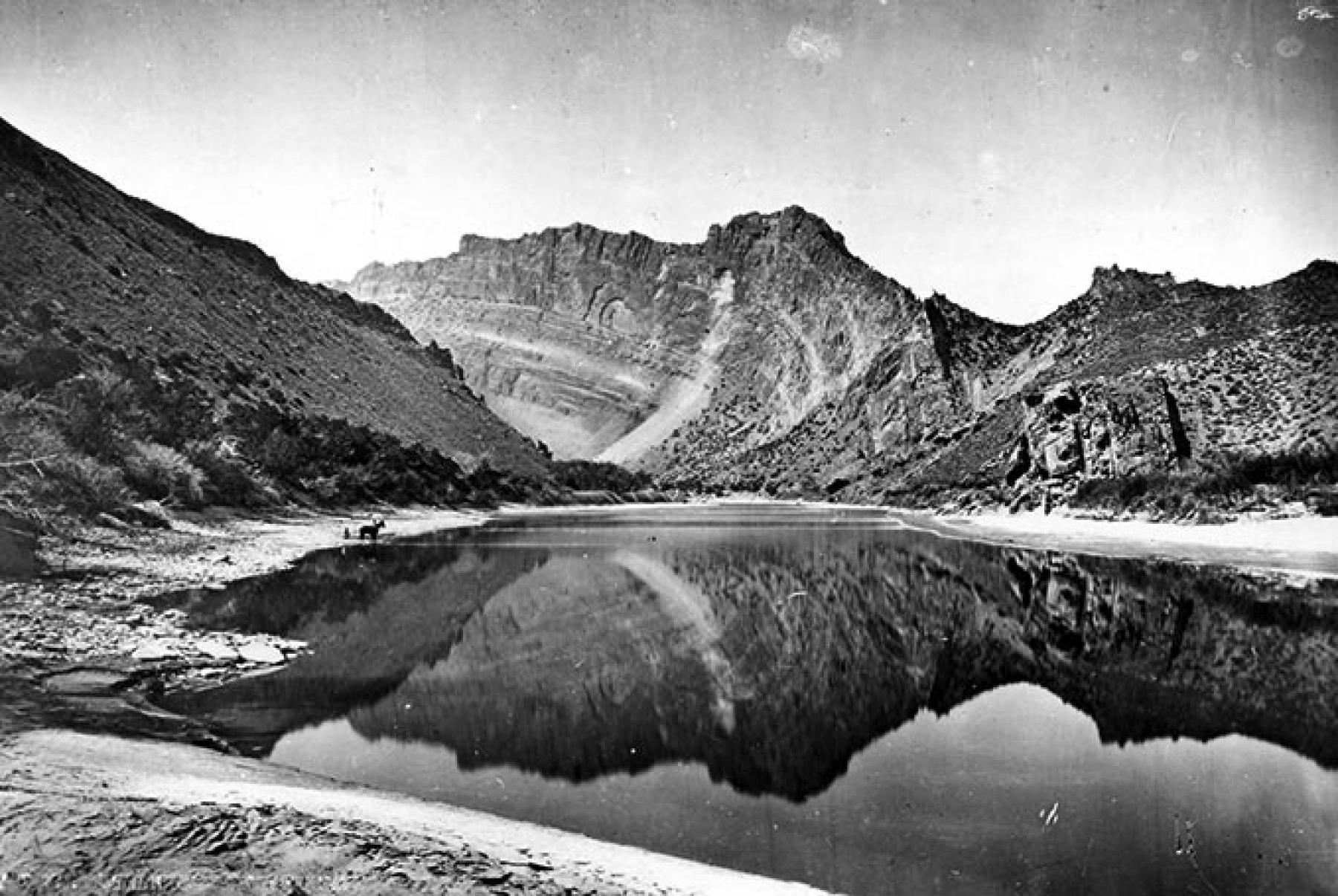

The author details the state of photography in the middle of the 19th century, reminding us of how far the technology has progressed in the past 170 years. In the early days, photos were taken on glass plates, which photographers had to develop themselves. All photos were black-and-white, and duplication was unknown. Jackson, on one of his early photography trips west, “packed an incredible amount of equipment amounting to hundreds of pounds,” including lenses, chemicals for processing photos, special papers and a portable darkroom.

The processing “included floating silvered albumin paper in a bath of silver nitrate, then fuming … [the photos] with ammonia once dry.” When taking pictures outdoors, which Jackson usually did, he “had to adjust his exposure times to a western sun and open sky … Exposure times had to be timed to outdoor light, and how long to leave a lens open was sometimes an uncertainty.”

Jackson realized almost immediately that he could easily sell his photos. His career jumped forward in July 1870, when Ferdinand V. Hayden invited Jackson to join his first survey party, slated to explore central and southwestern Wyoming Territory. In future years, Hayden led seven surveys to different regions of the West; Jackson was official photographer for them all, except in summer 1876, when he manned the Hayden Survey exhibit at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

Standouts from Jackson’s career include being the first photographer to document the geothermal and scenic wonders in future Yellowstone Park; his repeated adjustments to the many changes in photographic technology during his lifetime—continuing to achieve professional success; weathering severe privations to photograph various geographical features; and living to the age of 99.

Jackson biographers, including McNeese, are fortunate to have a wealth of primary source information at their disposal, since Jackson published two autobiographies, one in 1929, the other in 1940. Though the book, oddly, lacks an index, McNeese’s style is readable and accessible, making his book a good addition to Jackson lore.

Rebecca Hein is an assistant editor of WyoHistory.org

Read William Henry Jackson: Foremost Photographer of the American West