Available at Your Local Library: The Novel That Welcomed the Ku Klux Klan to Wyoming

By Leslie Waggener

In 1913, Wyoming’s Casper Record made an unusual offer to new subscribers: sign up for a year, and they’d throw in a free copy of Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman—a book that glorified the Ku Klux Klan as heroes. Eight years later, when Klan recruiters arrived in Wyoming, they found audiences already primed by this very novel to see hooded riders as defenders of American values.

When I published my article in the Winter 2024 issue of Annals of Wyoming about the Second Ku Klux Klan’s presence in the state, I had to leave a lot of material on the cutting room floor. Now I want to share some of that research—particularly the story of how Wyoming became such fertile ground for the Klan’s arrival in the early 1920s.

This isn’t just about what happened when Klan recruiters showed up in June 1921. It’s about how the stage was set years earlier—and that includes a novel that Wyomingites could check out from their local library or buy at their corner bookstore.

Dixon’s Dangerous Romance

Thomas Dixon Jr.’s 1905 book The Clansman glorified the Reconstruction-era Klan, portraying masked riders as protectors of white womanhood and Anglo-Saxon values. Although the novel focused on Black Americans as the threat, it established a template that the Second Klan would adapt to target Catholics and immigrants as well.

Dixon himself was a fascinating character—one of those larger-than-life figures who reinvented himself constantly as actor, lawyer, politician, Baptist minister, lecturer, and novelist. National newspapers, including those in Wyoming, regularly reported his sermons and lectures, often printing them in their entirety. Initially aligned with liberal reformers of the Social Gospel Movement demanding justice for immigrants and the “weak and helpless,” Dixon reversed course dramatically, launching what he called a crusade against the “black peril” and promoting an American-led, Anglo-Saxon “international brotherhood.”

Many Wyomingites were already familiar with Dixon and his philosophy when The Clansman was published in 1905. What I didn’t fully appreciate until I started digging through Wyoming newspapers was just how accessible this novel became across the state.

For Sale at a Store Near You

The Clansman wasn’t some obscure publication you had to special order. It was everywhere in Wyoming.

In 1907, Laramie residents could buy a copy at Mills Bookstore for 75 cents. In Cheyenne, Barry Brothers bookstore offered it in 1910 for 60 cents. Sheridan residents could purchase it in 1916 for 50 cents at Stevens, Fryberger & Co. The public libraries in Moorcroft and Wheatland stocked it for free lending.

But my favorite example of how mainstream this book became is that 1913 Casper Record offer mentioned earlier. For just two dollars, you could get a year’s subscription to the newspaper plus a “handsome cloth bound” copy of Dixon’s novel.

The Play Tours America—Wyoming Newspapers Take Notice

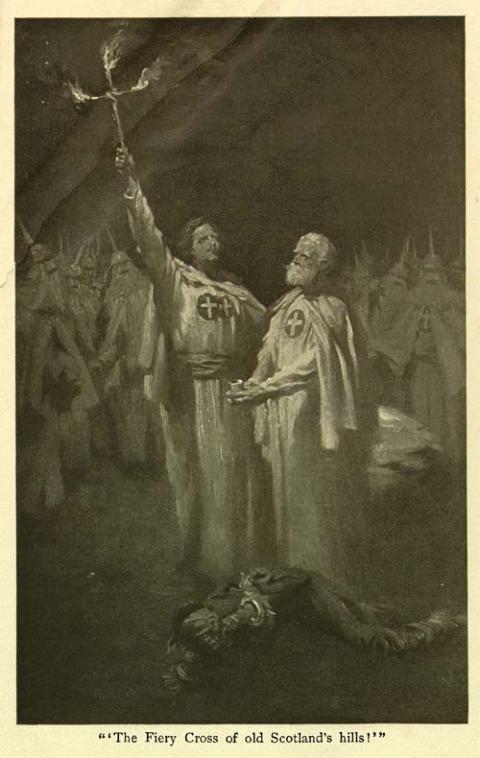

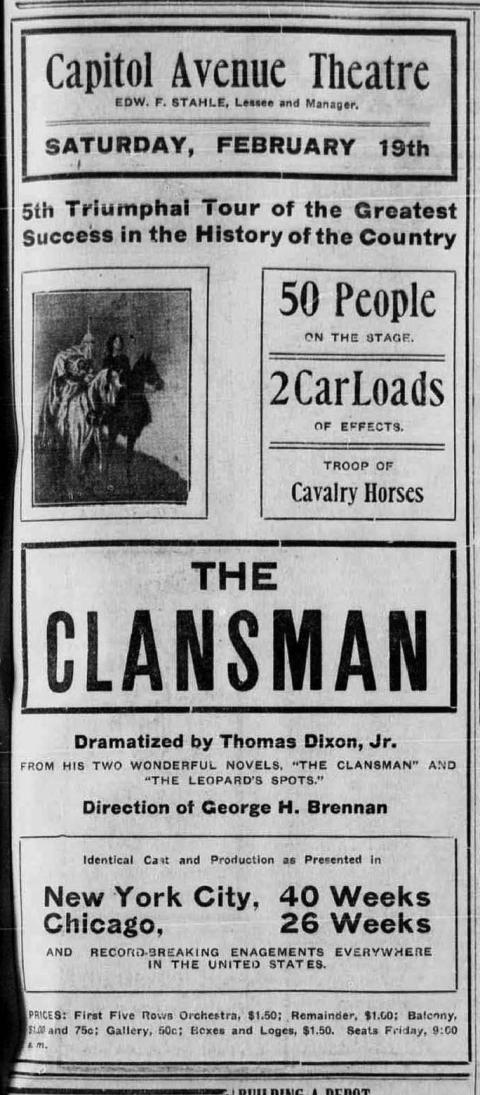

Soon after the book’s publication, Dixon adapted it into a play. During a five-year American tour beginning in 1905, Wyoming newspapers followed the production’s progress across the country—and the explosive reactions it generated.

Wyoming readers got regular updates about The Clansman’s controversial reception. In October 1905, The Laramie Republican reported that Dixon had to barricade himself in his hotel room in South Carolina against an enraged mob. The next month, The Cody Enterprise ran a story about a mob in Georgia—“wrought up to a high pitch of anger against negroes” by Dixon’s play—that lynched a Black man accused of shooting a sheriff. The Converse County Herald and The Wheatland World carried stories about Black communities demanding that authorities ban the production. When Philadelphia’s mayor halted a performance, The Laramie Republican reported that the decision had ended his political career.

When the play arrived for a Wyoming tour, state newspapers sensationalized it with language such as that of Cheyenne’s Wyoming Tribune, which promoted The Clansman’s appearance as the play's “5th Triumphal Tour” and “the Greatest Success in the History of the Country.” The article specifically celebrated “the big scene of the Ku Klux Klan in the third act” as having “made the drama celebrated from one end of the country to the other.” Audiences packed their local theater houses across the state.

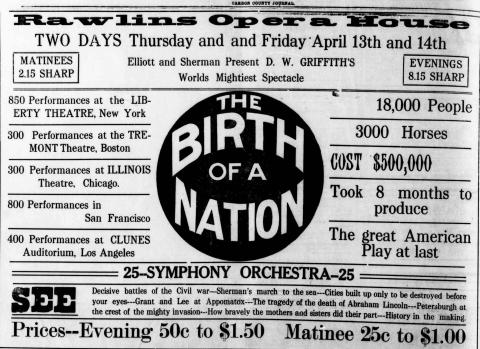

The Film Arrives: Birth of a Nation

In 1915, D.W. Griffith transformed Dixon’s novel into the film The Birth of a Nation. This landmark film—praised for its technical innovations but notorious for its racist content—brought Dixon’s vision to an even wider audience.

Like the play, Wyoming newspapers lauded the film. When it came to theaters across the state, it was advertised it as a must-see spectacle, emphasizing its epic scale and groundbreaking cinematography. The romanticized image of hooded Klansmen as heroes rescuing civilization had now moved from the page to the stage to the silver screen—and Wyoming audiences seemingly embraced it.

Thus, by the time actual Klan recruiters arrived in Wyoming in 1921, many residents had already been exposed to Dixon’s romanticized vision of the Klan through his novel, his touring play, and Griffith’s celebrated film. The template was set: a secret brotherhood defending “real” Americans against dangerous outsiders.

Dixon’s Second Thoughts

Here’s an ironic coda to Dixon’s story. By the time the Second Klan was thriving in Wyoming in the early 1920s, Thomas Dixon was claiming the new organization bore no resemblance to the noble order he’d portrayed. He declined an invitation to join and warned organizers that “if they dared to use the disguise in a secret oathbound order today, with the courts of law working under a civilized government, the end was sure—riot, anarchy, bloodshed and martial law.”

News of Dixon’s distancing reached even remote Wyoming. In February 1923, the Lightning Flat Flash noted the contradiction: “Apparently the panegyrist of the old klan can see no similarity between it and the klan of today.” But whatever Dixon’s misgivings about the Second Klan, it was too late. His romanticized portrayal—in novel, play, and film—had already primed a generation of Americans, including Wyomingites, to view the hooded order as defenders of American values.

Other Forces at Work

Dixon’s cultural influence was just one factor behind the rise of the KKK. World War I’s One Hundred Percent American Society had established chapters in nearly every Wyoming town, demanding conformity and punishing dissent—publishing members’ names in newspapers, threatening “slackers” with forced labor, and creating what one activist later called an era where “we suspected our best friends.” When the war ended, the Society disbanded, but the mindset persisted.

Meanwhile, Catholics—many of them Irish immigrants—had grown to ten percent of Wyoming’s population, and the Klan found fertile ground in existing anxieties about immigrants and foreign influences. Wyoming had already passed discriminatory laws prohibiting foreigners from owning firearms and restricting their employment.

Add to this Prohibition’s spectacular failure—with scandals, corruption, and typically law-abiding citizens making moonshine to survive Wyoming’s early Depression—and the Klan found an opening. They positioned themselves as enforcers of law and order who would step in where public officials had failed.

Figure 6. Internal Revenue Service agents Billy Hunter, Al Morton, and Chris Jessen confiscating illegal stills in Green River, Wyoming, July 11, 1926. Source: Otto Plaga Collection, American Heritage Center University of Wyoming.

The Stage Was Set

When I look at all these factors together—Dixon’s widely available novel, play, and film romanticizing the Klan; the wartime climate of suspicion and conformity; anxieties about immigration and Catholics; Prohibition’s failure; and a pervasive sense that law and order had broken down—I can see how Wyoming became what the Klan called “one of the most compactly and completely organized Klan states.”

The Klan didn’t create these fears and prejudices. They exploited them. And the groundwork for that exploitation had been laid years before the first kleagle arrived in Douglas in June 1921—including by a novelist who would later desperately wish he could take it all back.

For more on the Second Ku Klux Klan in Wyoming, see my articles in Annals of Wyoming, Winter 2024, and “Reborn in Robes: The Second Ku Klux Klan in Wyoming, 1921-1930” on WyoHistory.org.