Was John Muir racist?

The answer depends, not on Muir’s actions, but on how you define 'racist'

By John Clayton

(Editor’s note: John Clayton is author of "John Muir in Yellowstone” on WyoHistory.org.)

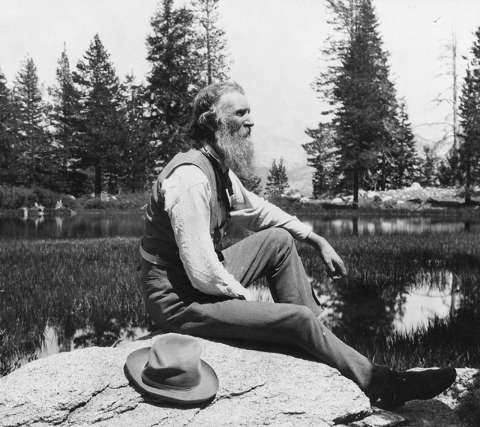

I love John Muir. I even wrote a book arguing that this much-heralded figure doesn’t get as much credit as he deserves. So I noticed when Sierra Club executive director Michael Brune called out the racism of the club’s beloved founder, John Muir. “Muir’s words and actions… continue to hurt and alienate Indigenous people and people of color who come into contact with the Sierra Club,” said his July 22 post on the club website.

My reaction? If John Muir is a racist, then so am I. And you know what? I’m OK with that. Indeed, that’s the point.

As many Muir defenders have condemned Brune’s statement, they’ve overlooked how much the definition of racist has changed in the last ten years. A racist used to be someone who believes that an entire race of people is inherently inferior, that any individual Black person is inherently less worthy than any individual White. This racism is morally repugnant and any decent person today will proclaim, “I’m not a racist!”

However, I hear today’s racial justice activists asking: After more than 50 years of this view of racism, why do Black people still face police brutality? Why do they still feel threatened in such harmless outdoor activities as “birding while Black” or “jogging while Black”?

The answer is that our society’s problems go beyond individual racists. Blacks are being held back by institutions stamped with racial prejudice. The way many white people have reacted to the George Floyd video shows that they can grasp this idea for an institution like the police. But do the racially-tainted institutions also include environmental groups? If not, why were only 0.7 percent of 2014–18 visitors to designated wilderness areas Black (compared to 13 percent of the total population)?

To achieve a truly equitable society, some people would tear down such institutions. Others hope they can be reformed. But to understand what to reform, we need to understand how they became tainted. That’s why, at the Sierra Club, Brune is talking about Muir.

Some Muir defenders are angry that Brune is judging a historic figure by today’s standards. And it’s true, the words racist and racism were hardly used during Muir’s life (1838–1914). Then again, Muir’s defenders are judging him based on 1980s standards. That’s the definition of racism they’re using when they ask if Muir’s words or actions implied a belief in racial inferiority. Their answer is correct for its time: although Muir did say some unfortunate things in his youth, he then said some better things in old age. Especially given his era, you can’t cancel him for morally repugnant statements.

But that’s an outdated meaning of the word racist. The idea of racism now centers on support for institutions that hold down Black and Indigenous people. Muir founded the Sierra Club, which for many years was exclusive, invitation-only, a sort of country club for hikers. By excluding people of color, the institution held them down. Furthermore, Muir supported a vision of national parks that excluded Indigenous history. By consciously erasing their presence, this vision held them down. Muir depicted wilderness as a Christian-tinged spiritual haven. Thus Muir-derived wilderness philosophy tended to exclude non-Christians, indeed non-White Anglo-Saxon Protestants—holding down others. Muir also hung out with a bunch of eugenicists, whose beliefs we now see as reprehensible. By failing to articulate how his vision of relationships to nature differed from theirs, he helped legitimize their ideas, which held down people of color.

I can express these concerns without judging Muir as a bad person. I believe that he acted in good faith, without malice toward any race. Rather than issuing judgments, the point of this discussion should be that unless we all reflect on how our apparently innocent actions end up leading to racial injustice, we will never achieve the racial justice that we say we want.

I’m frustrated that the word racist now has such a different meaning than it used to. (Likewise, a white supremacist used to be the crazy-extreme version of a racist, but now the words are basically synonyms: People who tacitly support systems that perpetuate white supremacy.) It’d be more convenient for me if we’d all agree to use a different word. But, I finally realized, the point is to consider the victims’ perspective, not mine. If people are still being killed or arrested or denied opportunities to shape environmental priorities because of their race, then the system is still racist. Am I actively seeking to change that system?

That’s why, in acknowledging Muir’s racism, I also acknowledge mine. I have too often failed to confront institutions that hurt Black and Indigenous people. I have written too many stories about natural history without asking why so many of my subjects were white males. I have too rarely spoken up when friends made hurtful comments. I’m sorry I did these things. I hope those (in)actions don’t make me morally repugnant; I hope people of color will give me another chance.

I like to believe that, if he were alive today, John Muir might say something similar.

John Clayton is the author of “Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands” (Pegasus, 2019). He lives in Montana.

Discuss this post on Facebook