Lost and Found

By Lena (Sunada-Matsumura) Newlin

“A cemetery is a history of people – a perpetual record of yesterday and a sanctuary of peace and quiet today. A cemetery exists because every life is worth loving and remembering – always.”

– Inscription on the welcome stone at Greenhill Cemetery, Laramie, Wyoming

Perhaps, in his last moments, his frozen fingers unbuttoned his wool coat, reached toward his heart into his shirt pocket, and took out the photo of the girl who was to be his wife. Perhaps as he closed his eyes, his calloused hand caressed the glossy paper, and he dreamt of holding her chin and soft skin to his lips. Kissing her dark eyes. And as he released his final breath and a tear froze as it trickled down his face, perhaps he felt warmed by love.

* * *

It was a late Sunday afternoon in September. The heat of the summer was past its peak, and the sky threatened a thunderstorm in the distance. My sunglasses—a makeshift hair clip on top of my head—kept the wind from blowing wisps of hair into my face. I walked toward the University of Wyoming campus through my neighborhood of cottonwood trees and 1950s-era houses—a hodgepodge of homes with brick and wood siding, hip and gable rooftops, some with yards nicely manicured and others with yards overgrown by thistle and bindweed. I could hear the sound of a freight train passing through the center of town a couple miles away—the rumbling echoing throughout the valley. It was a nice day for a walk, of course, a nice day to get outside for a little exercise.

But this wasn’t a lazy afternoon stroll through the neighborhood. This wasn’t a jaunt through campus, a birdwatching or flower-peeping excursion. Today was something different. I was on a search for something.

And I was hoping to find it in the cemetery.

* * *

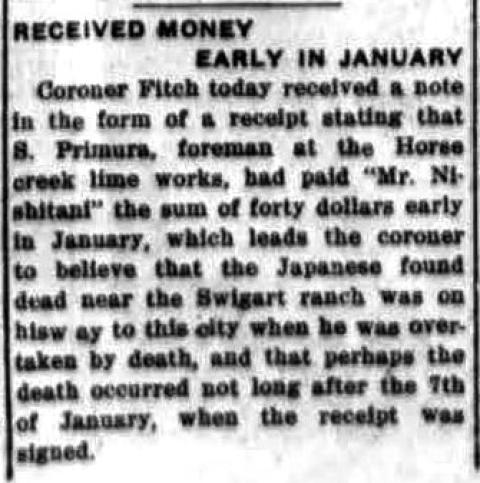

Perhaps it was to be his final task as a bachelor. A delivery. On horse, or maybe a wagon. Maybe on foot. He would collect the supplies for his employer, pay the $40. And then he would take a train to Seattle to meet and marry his bride. Bring her back to Wyoming, start a family. Be happy together. Become Americans.

* * *

Greenhill Cemetery sits in the heart of Laramie, Wyoming. Bordered on all sides by streets and obscured by a chain link fence and trees, it’s easy to forget that the final resting place of many of Laramie’s citizens, both historical and contemporary, is surrounded entirely by the University of Wyoming campus. I enjoy walking through the cemetery—its dirt paths, resident mule deer, large spruce trees and community gardens make for a peaceful and wind-protected refuge that attracts walkers and runners, in addition to those in mourning.

Established in the late 1800s, the cemetery has headstones of some of Laramie’s prominent early citizens. Names that also appear on local street signs and buildings: Edward and Jane Ivinson, Aven Nelson, Stephen and June Downey, Wilbur and Emma Knight, Nellie Oakley Lovejoy, and Nellis Corthell.

There are also plots without markers and plots with markers so weathered they are indistinguishable—some of Laramie’s forgotten or barely recalled citizens. These can be found in the northwest side of Greenhill Cemetery, in an area called Potter’s Field.

* * *

But something unexpected happened. Something went wrong. A snow squall—a blizzard—perhaps the one on January 9. Or maybe it was February 5. The kind that darkened the sky and blew snow sideways, that pierced exposed skin like daggers, that draped tumbleweeds in blankets of white, and hurtled them across the prairie like giant snowballs.

He lost the trail that wasn’t really a trail to begin with. He trudged through the sagebrush. Snow was already starting to drift from the wind and his feet felt the cold leach into his boots. He cinched tight the ear flaps on his hat, lifted the collar of his coat to protect the skin on his neck, covered his nose and his lips with the inside of his elbow. His eyes scanned the area for some kind of shelter, some kind of refuge. And after he’d circled the hills in a hypothermic stupor, he cleared his frostbit lungs, raised his voice and called out. Maybe in English; probably in Japanese. Perhaps he pleaded for help; perhaps he sang deliriously; maybe he sobbed an apology to the girl, who would have been his wife. But his voice was lost in the wind.

The year was 1914.

* * *

I had been reading a book, Japanese in Wyoming: Union Pacific’s Forgotten Labor Force. Authored by Daniel Lyon, a Japanese American from Cheyenne, Wyoming, the book gives an historical account of Japanese immigrant labor on the railroad in Wyoming beginning in 1892. Through black and white photographs, maps, and documents recovered from personal and historical archives, the author uncovers and narrates the cultural and economic contributions that Japanese immigrants brought to Wyoming, the hardships and injustices they experienced as immigrant laborers, and the legacy they left in the state. I was interested in this history because, you see, my ancestors were Japanese immigrants in Wyoming who worked for the railroad. In fact, a photo of my great grandfather, M. Sunada and his brother, C.N. Sunada, appears in the book (p. 60).

In a chapter titled, “Wyoming Wind,” the author recounts a tragedy in October 1908 when “gale-force wind” caused a work train to derail between Laramie and Cheyenne. Six men were killed, including two Japanese. Buichi Mori and Osomu Hiromota were both 29, and, according to the author, were buried at Potter’s Field in Laramie’s Greenhill Cemetery (p. 86–87).

I began to wonder about these two men. Mori and Hiromota. Who were they, and why were they in Wyoming? Did anyone mourn their loss? Did anyone leave them flowers? Visit their grave? They were just three years older than my great grandfather, Morijiro Sunada. The one whose picture was in the book. I felt pangs of grief in my body.

I needed to go to the cemetery.

* * *

I looked up the gravesite plot locations on the cemetery’s website and found a map of the general area. I couldn’t find Mori’s name, but it said Hiromota was in Potter’s Field: Lot RO W13, Space 5.

I’d never been to Potter’s Field before. I looked at the map. Walked through the gates, turned north, proceeded past the rows of older and newer headstones. And then I came upon an open field. The grass was freshly mowed, and there were only a handful of stones. But the depressions in the meadow—stationary waves, miniature rolling hills—suggested that despite the lack of headstones, bodies rested below the surface. This was Potter’s Field. This was where “the city and county buried its undesirable and the indigent” (Greenhill Cemetery brochure #24.) It was unclear how to identify the lots and the rows and the spaces, so I walked around to the few headstones that were there. Harley and Elizabeth Swayze: died in 1927; Sarkis Raisan: died in 1917; Johnny McLennan, “infant son,” died in 1916; Joe Martin, a Black American lynched in Laramie in 1904 and who was memorialized with a stone in 2021 by the Albany County Historical Society; and some stones so old that the inscriptions had been completely erased.

And then, I came across a granite stone laid flat, not upright. Gray in color with rough edges. On the smooth surface, the inscription: Japanese writing. This had to be it—either Mori or Hiromota’s stone. But what did it say? Why only in Japanese? I tried Google Translate and it came up with nothing intelligible. I wondered: who bought the stone? And when? It looked new, not like the other stones in Potter’s Field. Maybe 30, 40 years old? I snapped a photo and made my way back home. I would go to the cemetery office the next day to inquire.

* * *

Perhaps the girl he was to marry was already on the ship. It was February, and she carried a photo of him in his younger days–handsome, with a boyish smile, wearing an expensive suit. A marriage arranged by a Japanese matchmaker. She hoped that he would be wealthy, that he would be smart, that he would be gentle.

But when she arrived at the dock on a rainy, gray day, with all of the other brides and their photos of handsome young Japanese men, she was left alone. The man in the photo, the man she’d dreamt about, the man she would marry, the man she would build a life with in America–he was not there.

And with no one to claim her, with no one to marry, as had been promised, like a package without enough postage, perhaps she was returned, sent back.

To Japan.

* * *

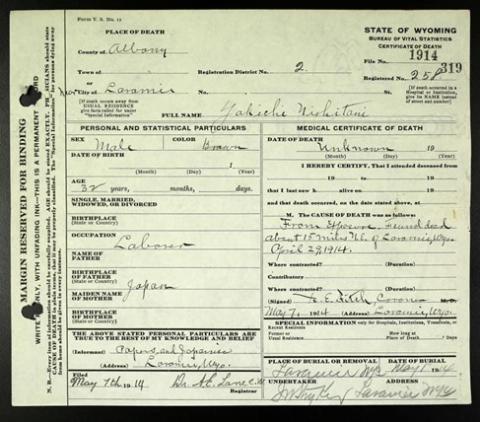

I posted the photo of the headstone on a Japanese family history Facebook group. Can somebody help me with the inscription and tell me what it says, I asked. Within 10 minutes a notification popped up. The headstone belonged to neither Mori nor Hiromota. They gave me another name. And then a very technical linguistic discussion ensued about the Japanese characters on the headstone: some are “archaic/nonstandard kanji.” So maybe it isn’t a newer stone after all? Within an hour, I received another notification. Someone had found the death certificate of the deceased.

He was a laborer from Kagoshima prefecture, which, according to Google, is on the southern tip of Japan’s Kyushu island and is known for its subtropical climate, hot springs, and volcanos. He was 32 years old.

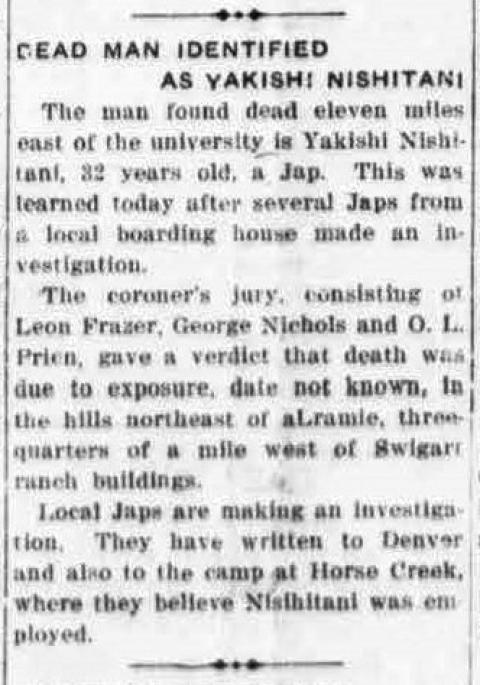

His body was found about 15 miles northeast of Laramie on April 29, 1914. The coroner said the cause of death was “exposure.”

His name was Yakichi Nishitani.

* * *

The next day, I spoke with the manager of the cemetery. I asked him about Nishitani’s headstone and Mori and Hiromota. The documentation from that time was not good, he explained, so we don’t know a whole lot. But that headstone has been there since before I started working here, 32 years ago. He sent me some old newspaper articles about the three men who he had found in a digital archive.

* * *

A few weeks later, when the leaves were past their peak colors of golds and reds, when the air against my skin felt crisp, when the sun was low in the sky, I returned to Potter’s Field in Greenhill Cemetery. I took the same path as before, walked over the uneven grass—a bit crunchy now. I found the Japanese stone. I knelt beside it, cleaned it off with my hand, and then: I placed flowers and an origami crane on Yakichi Nishitani’s grave.

* * *

Yakishi Nishitani died five and a half years after Buichi Mori and Osomu Hiromota were killed in the railroad accident. They are all buried in Potter’s Field, in Greenhill Cemetery in Laramie, Wyoming. They were separated in age by only a couple of years. Nishitani’s headstone is the only evidence of Japanese in Potter’s Field.

Perhaps they knew each other from back home; perhaps they grew up together–went to school together, played in the ocean, explored the volcanos, soaked in the hot springs together, sailed across the sea in the same ship. Perhaps they fantasized about settling in America, about falling in love with a nice girl, marrying her, growing old together. Perhaps in Wyoming they retold stories of their youth, reminisced about old lovers, laughed with each other to disguise their pangs of homesickness, their stretches of loneliness.

And perhaps now, they will rest in peace knowing that indeed, their lives “were worth loving and remembering.” Because now, they have someone who will decorate their final resting place.

Related information

Before Heart Mountain: Japanese in Early Wyoming by Dan Lyon.