The Forgotten Scrapbook: Monte Grover and Laramie’s Red-Light District

By Leslie Waggener and Emma Comstock

Scrapbook Rediscovered

When Leslie Waggener arrived as a newly minted archivist at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center in 2000, whispers of Monte Grover’s scrapbook occasionally drifted through the Reference Department where she worked. It wasn’t until two years later, when the AHC organized a historic tour of Laramie’s Greenhill Cemetery, that she truly encountered Monte’s story. As staff members and volunteers assumed the roles of those buried there, she was assigned to give voice to Monte – a woman whose remains lie in an unmarked grave beside the more commemorated Christy Grover.

Standing by that unacknowledged patch of earth, portraying a woman whose life had been largely forgotten, she developed an interest in Monte that has lasted nearly 25 years. Monte's story – heartbreaking in many ways – continues to haunt her, driving my search to uncover more about this complex woman who lived on society’s margins while yearning for respectability.

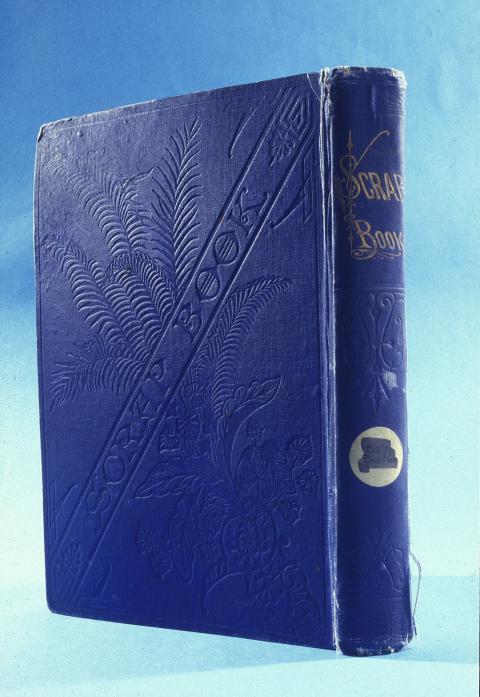

Hidden among the countless treasures at the AHC sits her unassuming scrapbook. Discovered in the late 1990s during preparations for a Victorian books exhibit at the Center’s Toppan Rare Books Library, this rare artifact is one of the only surviving firsthand accounts from a 19th-century brothel madam. This chance discovery proved significant – firsthand accounts from prostitutes of that era are exceedingly rare. Most women in “the life” were either illiterate or left no written records. What we know typically comes from newspaper accounts, court documents, and census records that often depict these women through the lens of moral judgment rather than their lived experience.

From Mamie Lambert to “Monte” Grover

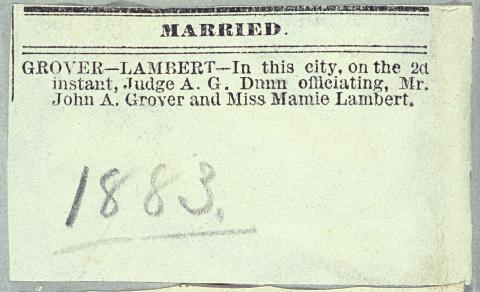

Before becoming a prominent figure in Laramie’s vice economy, Christy Grover had established herself in Cheyenne’s infamous prostitution scene. The 1880 census records show her living in Cheyenne at the house of a madam named Ida Hamilton, where she worked at the legendary House of Mirrors, a well-known parlor house. Christy moved to Laramie around 1880, where she rapidly accumulated wealth and property. Shortly after her arrival, she married John A. Grover and contracted with carpenter L.M. Schroeder to construct two houses in Block 200 on South B (now Grand Avenue). This property would eventually become the site of “an enormous Victorian mansion” that housed her brothel operation, which provided high-end services to Laramie’s clientele.

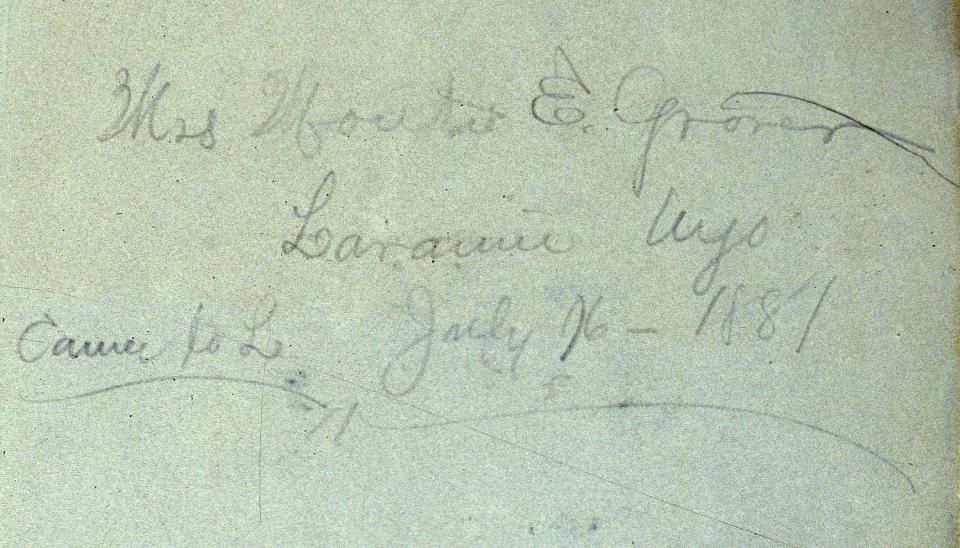

Mamie Lambert, a young woman of about 23, arrived in Laramie from Iowa in 1881, when the town had begun to settle from its early boom days. Newspaper clippings in her scrapbook suggest she may have previously worked as a prostitute in Chicago. Shortly after her arrival, she was hired by Christy Grover to work in her brothel. The young Mamie, soon known as Monte, quickly became part of the Grover establishment.

Monte developed two passionate interests during this time: the idea of becoming a married woman and, specifically, marrying John Grover, Christy’s husband. John would become the consuming passion of Monte’s life, a fixation that would shape her future in dramatic ways.

A Suspicious Death and a Swift Marriage

The relationship between Monte and Christy soon deteriorated, setting the stage for a tragedy that would forever change both women’s lives. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, Christy had allegedly argued with Monte over a theft before retiring to her room in anger. John Grover later reported hearing a gunshot and finding Christy with a fatal bullet wound to her temple. She died on February 19, 1882, at the young age of 30. While officially ruled a suicide, the circumstances were considered suspicious by many in the community, particularly given the events that followed.

After Christy’s death, John wasted no time in claiming her substantial estate, valued at $6,246.25 (equivalent to over $170,000 today). This considerable sum allowed him to purchase a saloon at the corner of Second Street and Ivinson Avenue, while also maintaining control of the brothel properties. The brothel at the corner of Third and Grand, which had been Christy's primary business, continued operations and became known as “Grover’s Institute,” which stood at what is now 214 E. Grand Avenue.

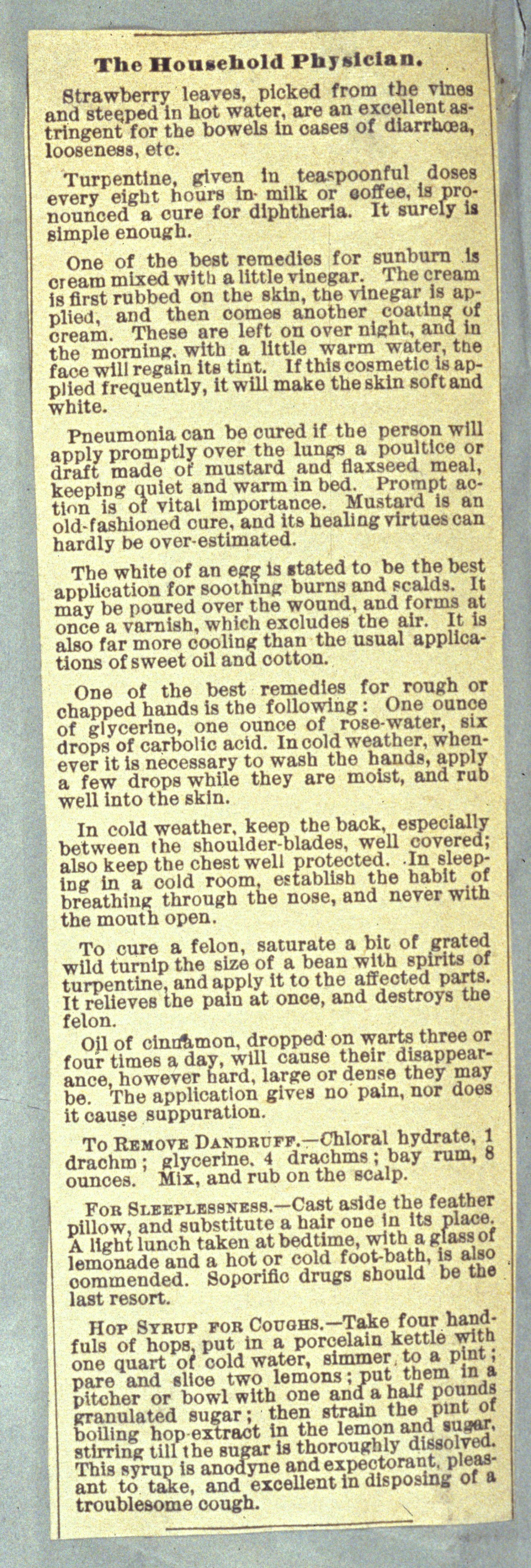

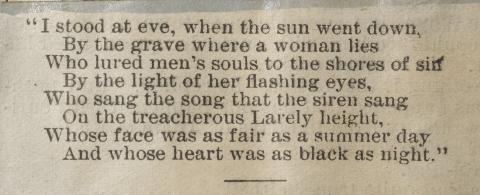

John and Monte married in October 1883, just twenty months after Christy’s death, and Monte immediately took over management of Grover’s Institute. Carol Bowers, whose 1994 Master's thesis researched Laramie's Victorian-era brothels, documented that, during Monte's time as madam, she divided her attention between managing Grover’s Institute on Grand Avenue and overseeing a second brothel owned by her husband at 707 4th Street, demonstrating the scale of their operation. Her scrapbook reveals her delight in her new status as a married woman. She collected household remedies, romantic poems about couples growing old together, and stories featuring heroic, trustworthy men named John – a stark contrast to the realities of her professional life and marriage.

A Victorian Woman on Society’s Margins

Monte’s scrapbook offers a fascinating glimpse into her inner life. Despite her profession, she collected newspaper clippings that reflected the attitudes and aspirations of proper middle-class Victorian women. Bowers noted that Monte seemed able to separate her professional reality from her idealized inner life.

As Comstock observed in her 2023 post on the University of Wyoming's American Heritage Center blog, Monte pasted articles about brothels and saloons alongside poems and anecdotes that celebrated Victorian domesticity. This duality reveals how women like Monte navigated the contradiction between their public and private selves in a society that marginalized them. [Scroll down to see a collection of images and pages from the scrapbook]

A Marriage Deteriorates

By 1887, Monte’s marriage to John had begun to deteriorate. The entries in her scrapbook grew increasingly morbid, preoccupied with death and longing. While the exact reasons for their marital troubles aren’t documented, they likely stemmed from issues common in such relationships: abuse, philandering, and financial exploitation.

As Bowers documented, Monte’s mental health declined precipitously in 1895. She began refusing food, claiming someone was trying to poison her. By autumn of that year, she had wasted away from around two hundred pounds to just seventy-five. Monte died on October 13, 1895, at the age of 37.

Bowers noted that, like with Christy’s death, the conclusions of the Coroner’s Jury regarding Monte’s demise were largely based on John Grover’s testimony. Despite some uneasiness about Grover’s potential role in the matter, the jury ultimately ruled that Monte’s death was attributable to “starvation caused by insanity.” In a strange coincidence that Bowers highlighted, John had purchased a burial plot next to Christy’s grave just seven months before Monte’s death. Monte was buried there in an unmarked grave, while Christy had a proper headstone.

Laramie’s Brothel Economy

Despite an anonymous writer’s lament in The Daily Boomerang in 1887 about “shameless women as vile if possible as the men who support them,” Laramie’s brothel district persisted as an economic pillar of the community for more than six decades. Rather than eradicate prostitution, the city typically moved to regulate it.

As Bowers documented in her thesis, Christy Grover’s brothel demonstrates the economic significance of these establishments. Bowers' research into historical records show she owned luxury items including a $500 piano (an enormous sum at the time), fine glassware, mirrors, walnut and ebony furniture, and silk upholstered chairs. She maintained accounts with prominent local businesses like Holliday & Stryker’s and Trabing Grocery, where she purchased expensive items for the women she employed and fine liquors for guests.

The Business of Vice in Laramie

After Monte’s death, John Grover was ordered by the Laramie City Council to close his operations. However, before leaving town, he rented his property to another madam named Minnie Ford, ensuring the continuity of the business.

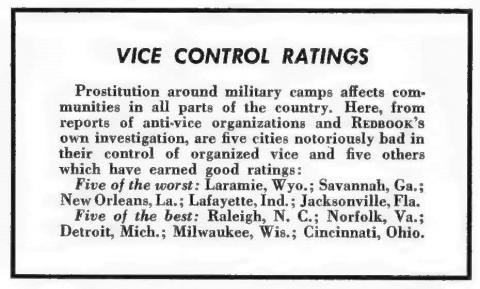

Up until 1954, brothels operated out of many downtown Laramie business fronts. They were more often curtailed by federal government intervention during wartime than by local pressure. The brothel workers contributed significantly to the city treasury through routine fines collected during symbolic police raids.

Storefront owners valued the women’s cash-based business in an era where credit dominated commerce. As consumers with tangible cash, prostitutes and madams were dependable spenders with tastes for luxury goods. Local authorities generally tolerated the red-light district as long as madams like Mabel Hartley and Dollie Randal, identified through Comstock's research, kept their establishments relatively quiet and trouble-free.

Bowers documented that the women were required to undergo regular physical examinations by a doctor to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases – with the women themselves responsible for covering the costs of any treatments.

The End of an Era

Laramie’s brothel district operated relatively unchanged until January 1954, when Redbook magazine published an article titled “Sex Traps for Young Servicemen” that mentioned Laramie. Though the reference was brief, it alarmed local officials and University of Wyoming administrators, including President George “Duke” Humphrey, who worried about damage to the university’s reputation.

On February 24, 1954, Mayor Oscar Hammond declared the immediate closure of the red-light district. However, according to retired Wyoming educator Louise A. Jackson, as late as the summer of 1960 at least one brothel was still operating. While waiting for a shoe repair, Jackson recalled being warned by the repairman not to wait on the sidewalk near First Street and Ivinson Avenue, lest she be mistaken for a “street girl.”

A Forgotten Legacy

Today, Monte Grover’s scrapbook in the Toppan Rare Book Library stands as one of the only surviving artifacts that testifies to Laramie’s brothel history. Monte herself lies in an unmarked grave beside Christy Grover in Greenhill Cemetery, her existence largely forgotten.

Yet her scrapbook tells a poignant story of a woman who dreamed of a happy marriage and a contented life while navigating life on the margins of Victorian society. It also documents an important aspect of Wyoming’s economic and social history that was often deliberately obscured but played a significant role in shaping communities like Laramie.

Author’s Note: This article was adapted from a post by Toppan Library Cataloger Emma Comstock for the AHC’s blog Discover History (https://ahcwyo.org/2023/02/13/a-madams-scrapbook-remnants-of-laramies-red-light-district/) as well as Carol Bowers’ 1994 thesis, “Less Than Ladies, Less than Love: Prostitution in Laramie, Wyoming, 1868-1920, for the University of Wyoming History Department, and Leslie Waggener's newspaper research.

![Inside cover of Monte’s scrapbook, one of the few surviving artifacts from 19th-century sex workers that documents Laramie’s brothel history. Inside cover pages of the scap with handwriting, "Mrs. [illegible] E Grover, Laramie, Wyo July 16 -1881"](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2025-05/Image%203_0.jpg?itok=3xws-Xl4)