Carrie Arnold’s Pen and Ink Holidays

By Leslie Waggener

When Denver attorney Bill Lagos wanted to send holiday greetings to friends and family, he didn’t reach for store-bought cards with generic winter scenes. Instead, he commissioned elegant pen-and-ink drawings of the Wyoming mining towns where he grew up—Hartville, where he was born in 1922, and Sunrise, where he attended school during the Depression. Artist Carrie Arnold brought these Wyoming places to life.

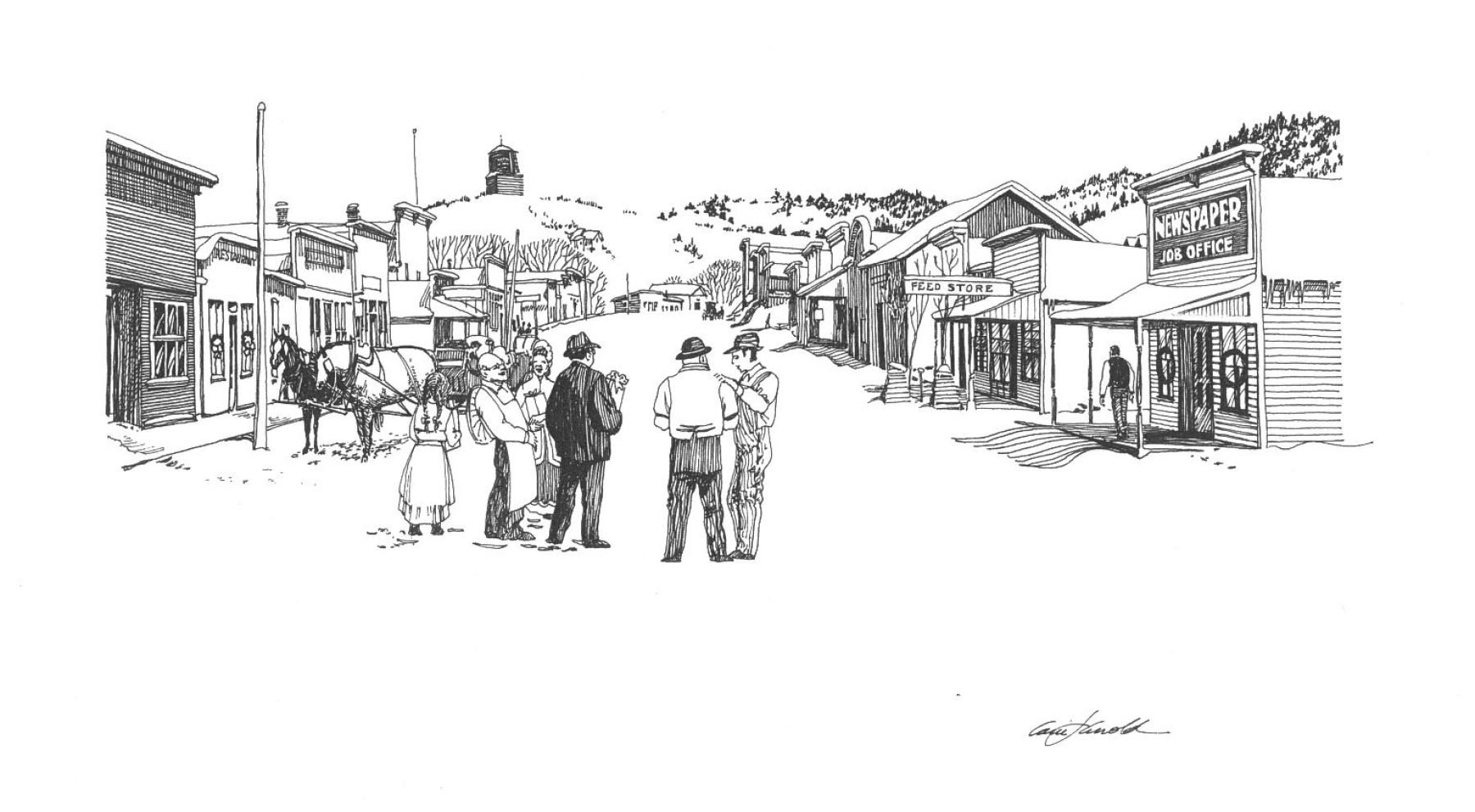

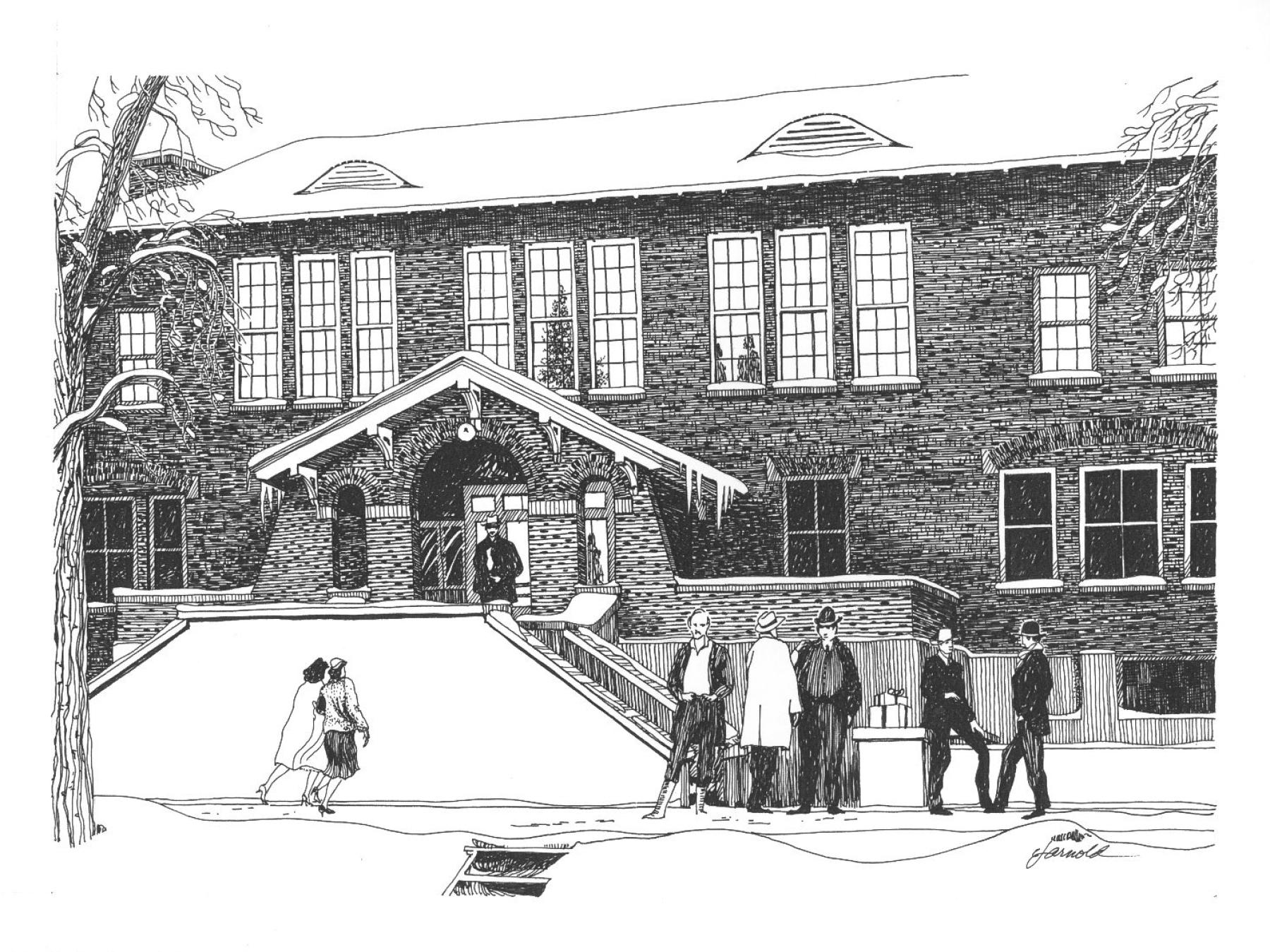

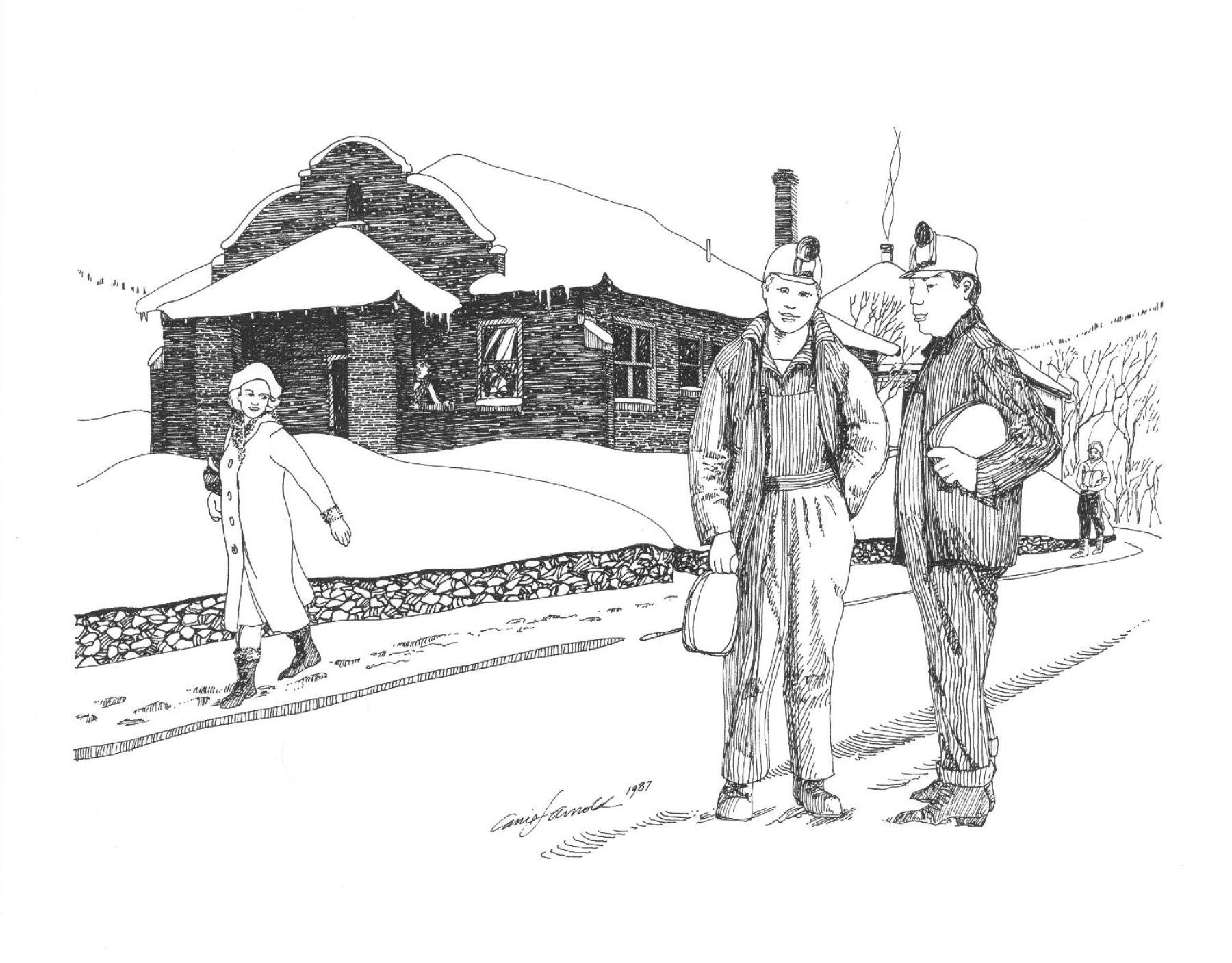

Between 1971 and 1997, Arnold crafted a remarkable series of Wyoming winter scenes for Lagos, expanding beyond Hartville and Sunrise to include Guernsey, Laramie, and other communities across the state. These weren’t simply pretty pictures—they were carefully researched historical documents rendered in graceful lines and animated by Arnold’s signature touch: people going about their daily lives.

Carrie Arnold’s journey to becoming the artist behind these Wyoming scenes was anything but conventional. Born near Greeley, Colorado in 1944, she attended the University of Northern Colorado before moving to Denver in 1965. There, she founded a successful petroleum map business—a decidedly technical venture she and her husband sold in 1972.

But Arnold’s true passions lay in Western history and art. She had begun painting portraits in high school and later developed her distinctive style as a pen-and-ink illustrator for Western books and cookbooks.

Arnold’s process was meticulous. Working from old photographs, she would visit Wyoming sites and talk with Wyoming natives to ensure historical accuracy. Her drawings captured Hartville and Sunrise in overview, along with intimate views of the old jail, schools, churches, the YMCA, and historic homes. Each building was rendered with precision, but never felt sterile or lifeless.

That’s because she understood something essential: buildings don’t exist in isolation. In her drawings, people walk down snowy streets, gather outside churches, and go about their business. These small human details transformed historical documentation into living memories, making viewers feel they could step into these Wyoming winter scenes and join the townspeople of decades past.

Through Arnold’s careful pen work, Wyoming’s frontier mining towns came alive again each December, their streets filled with snow and the shadows of people who once called them home.

The Carrie Arnold papers are housed at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie.