- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Battle At Bonepile Creek: The 1865 Sawyers Expe...

Battle at Bonepile Creek: The 1865 Sawyers Expedition

“The bluffs around at sunrise were covered with Indians to the number of 500 to 600, and fighting was commenced by their charging down over the plain.”

Hundreds of warriors charging at dawn on a group of U.S. soldiers fulfills every Hollywood cliché of the “Wild West.” Add to this that the fighting occurred along a creek named “Bonepile,” and surely this battle took place on a Los Angeles soundstage. Fanciful as they sound, however, the events on a hot August morning in 1865, 10 miles south of present Gillette, Wyoming, were very, very real.

Image

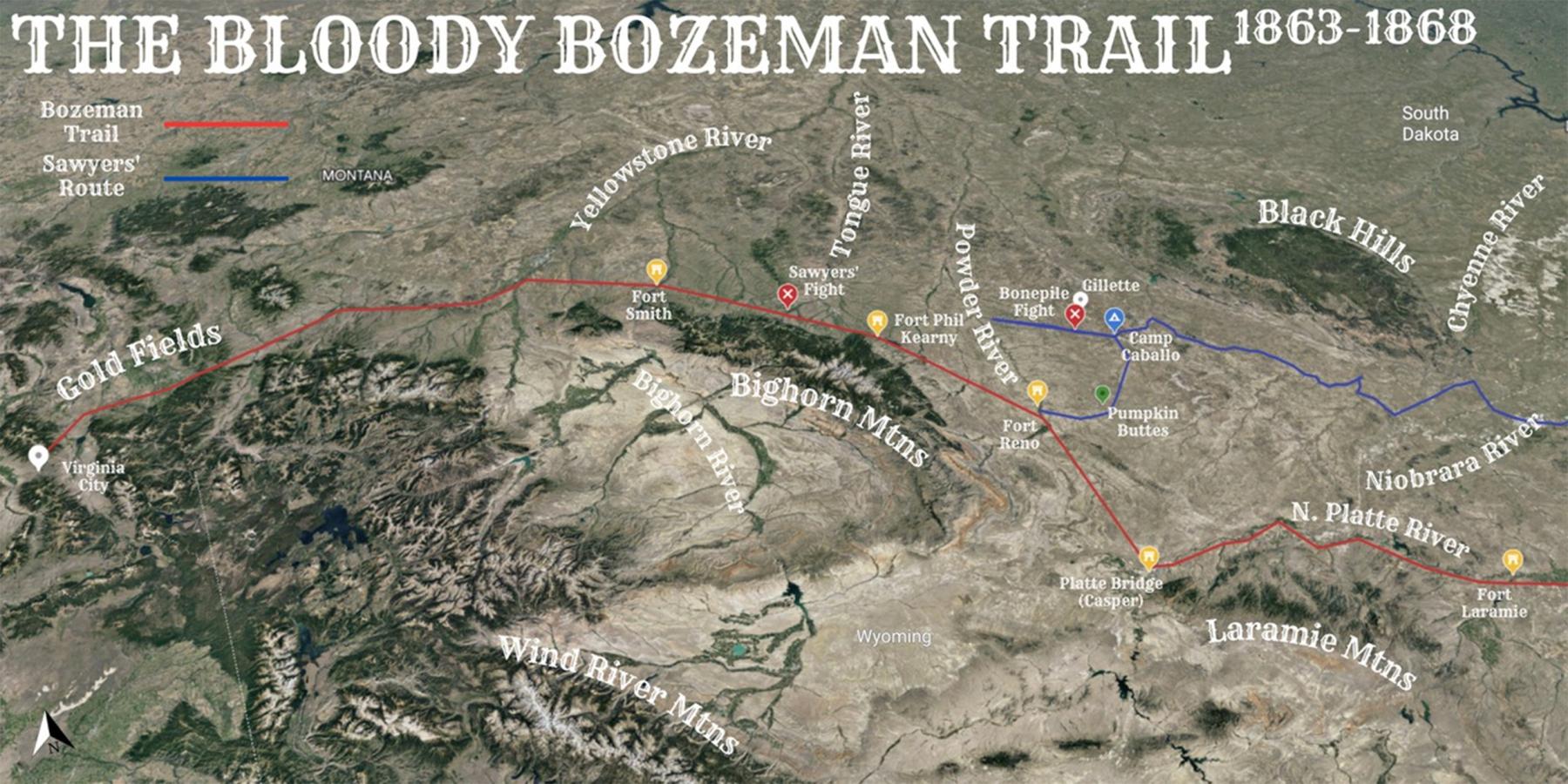

Gold in Montana

In 1863, as the Civil War raged in the east, prospectors in present western Montana discovered gold. Miners flocked to the valleys around Virginia City, Montana Territory, and in just three years extracted $30 million worth of gold. But getting to Montana was not easy, and would-be miners’ eagerness for wealth started a race to develop faster routes.

Hoping to capitalize on the gold fever, Iowans proposed a route west following the Niobrara River across northern Nebraska Territory. Cutting hundreds of miles off the existing Platte River Road, the proposed route held the advantage—at least from an Iowa resident’s perspective—of moving the primary “jumping off” point from Omaha to Sioux City, Iowa. Iowa representatives convinced Congress to authorize $50,000 for a road-building expedition. But like the more infamous Bozeman Trail, this new route still had a problem. It passed through Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, prime hunting ground promised by treaty to Native tribes.

Sawyers’s 1865 Expedition

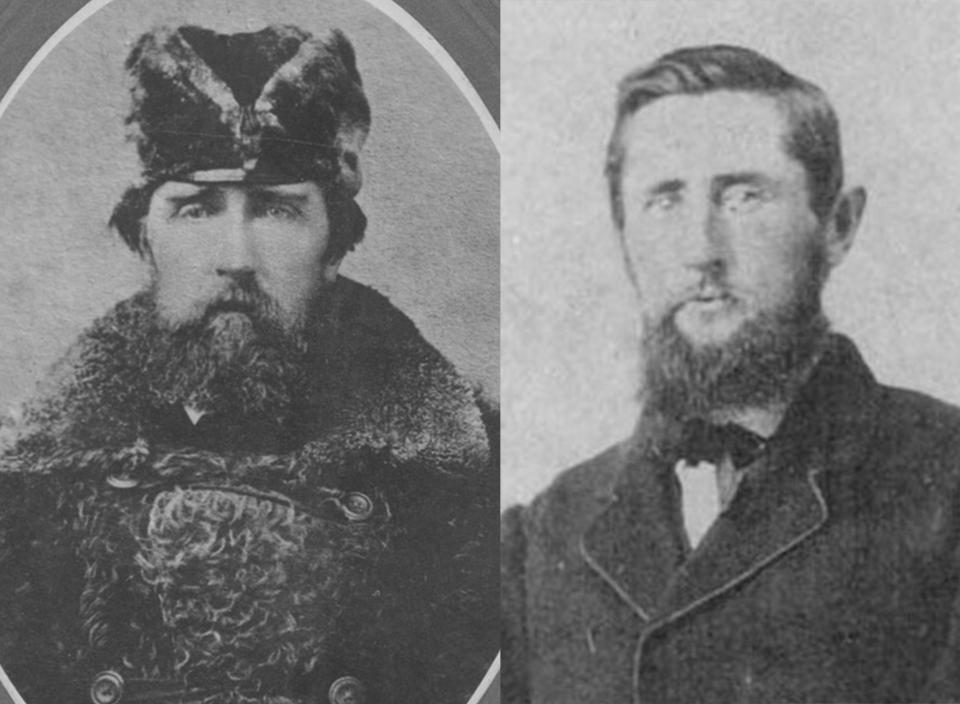

To lead the Niobrara-Virginia City Road Building Expedition, Iowa Congressman Asahel W. Hubbard picked James A. Sawyers. The dark-haired, 6-foot-4, Tennessee-born Sawyers served in the Mexican-American War before coming to Sioux City in 1857. He rejoined the Army at the outbreak of the Civil War, and as a lieutenant colonel commanded the Northern Border Brigade. The unit disbanded in late 1864 and Sawyers was discharged from military service.

Now a civilian, Sawyers commanded a party of 196 civilian men—including his brother Newell Sawyers—and 81 wagons. Initially, Rep. Hubbard promised James Sawyers a military escort of 200 cavalry troops. However, the Army only provided 118 men of the 5th U.S. Volunteer Infantry.

When Sawyers petitioned for further assistance, he received an additional 25 men from Company B, 1st Battalion Dakota Cavalry.[1] The military escort fell under the command of Capt. George W. Williford. A native of Illinois, Williford joined the Army at the beginning of the Civil War. The 29-year-old Williford clashed with Sawyers whom he believed “incompetent.” In turn, 41-year-old Sawyers thought Williford “fainthearted.”

Image

As the expedition traveled west across Nebraska following the Niobrara River—roughly the route of today’s U.S. Route 20—they marveled at the endless prairie. Sawyers, a devout Presbyterian, ordered the expedition to halt every Sunday to observe the Sabbath, a welcome rest from the task of digging stuck wagons out of the loose Nebraska Sandhills. Departing the Niobrara River at Rush Creek—30 miles east of present Chadron, Nebraska—they traveled northwest, first finding the White River and then the Cheyenne River which they followed into the “sterile country” of eastern Wyoming. With the Black Hills visible to their north, Sawyers’s party found the Belle Fourche River on Aug. 4 and from there traveled westward towards the Powder River Basin.[2]

The Powder River Expedition

At the same time Sawyers’s civilian expedition made its way into Wyoming, the U.S. Army launched its own Powder River Expedition. As a punitive measure for the tribes’ July 26, 1865 attack on Platte Bridge, Brig. Gen. Patrick E. Connor was ordered by General Grenville M. Dodge to “make vigorous war upon the Indians and punish them so that they will be forced to keep the peace.”[3]

News of Connor’s expedition reached Sawyers on Aug. 1 through Lieut. Daniel M. Dana. Williford had sent Dana to Fort Laramie to retrieve supplies—an action that grated on Sawyers, as he blamed the low Army supplies on Williford. Initially, news of Connor’s expedition seemed irrelevant to Sawyers, as he intended to reach the Powder River by traveling north of the Pumpkin Buttes while Connor, traveling on the Bozeman Trail, skirted the buttes to their south.[4]

Traveling north of Pumpkin Buttes, Sawyers made camp along a “stagnant” Caballo Creek on Aug. 9, 1865. There, Sawyers encountered the great mineral wealth Campbell County is known for today, seeing “large quantities of first-rate bituminous coal… I should think it almost inexhaustible.”

From the coal-laden campsite, Sawyers’s men traveled another 32 miles westward. Scouts found the Powder on Aug. 11, but reported the “very bad lands”[5] made terrain impassable for the wagons. In addition, the party suffered from dry conditions. The expedition’s engineer, Lewis H. Smith, wrote in his diary, “not much water for cahattle [sic] which are suffering from want therof. [sic].” Facing these hardships, Sawyers decided to turn the expedition around. They would return to Caballo Creek and make for the Powder on the south side of Pumpkin Buttes.

Image

Battle of Bonepile Creek

Want of water and “excessive” 90-degree heat continued to plague the expedition on Aug. 13. Around noon, 19-year-old teamster Nathaniel Hedges traveled a few miles ahead of the main body to scout for water. Finding water at Bonepile Creek, Hedges began watering the horses when he was attacked by a group of Cheyenne warriors lying in wait. Fellow teamster Albert Holman remembered “seven arrows had penetrated his breast; a bullet hole was in his cheek and several in his body. His head had been scalped, leaving bare the entire skull.”

After the Cheyennes killed Hedges, Sawyers reported they made a “dash on our herd and stampeded and drove off eight cavalry horses.” Fighting back, Sawyers’s men wounded at least one Cheyenne and bought themselves enough time to continue another 10 miles, hoping to reach Caballo Creek. But darkness closed in, making travel impossible and Sawyers’s men corralled on top of a small knoll. That night, 5th U.S. Volunteer Infantryman John Colby Griggs wrote in his diary, “no one allowed to sleep tonight” for fear of Indian attack.

The next day, they used wood from one of the old wagons to construct a crude coffin for Hedges and buried him in an unmarked grave. The men used their wagons to form a rudimentary fortification and dug rifle pits on top of the knoll. To keep watch, they set up pickets on nearby hill tops. While Pvt. Ulrick Jarvis of the Dakota Cavalry manned a picket, a group of 12 to 15 Cheyennes sneaked up on him. Fortunately for Jarvis, he heard the warriors and escaped. Scampering down the hill, Jarvis fired warning shots to alert the main expedition. With the warriors hot on his heels “with the speed of the wind,” Jarvis made it back to safety, losing only his hat. Throughout the day, the Cheyenne attempted to run off the expedition’s livestock and each time Sawyers’s men successfully fought them off. According to Griggs, 10 Native warriors were killed, while Sawyers lost no one this day.

The next morning, Aug. 15, Sawyers wrote, “the bluffs around at sunrise were covered with Indians to the number of 500 to 600, and fighting was commenced by their charging down over the plain and shooting into the corrall [sic].” After the initial ambush, Sawyers’s men had time to dig foxholes, corral the wagons and set up their two 12-pound mountain howitzers; Sawyers proudly noted his men could repulse each charge of the Native warriors. After two days of this fighting, the Cheyennes realized further fighting would not be successful, and they called for peace.

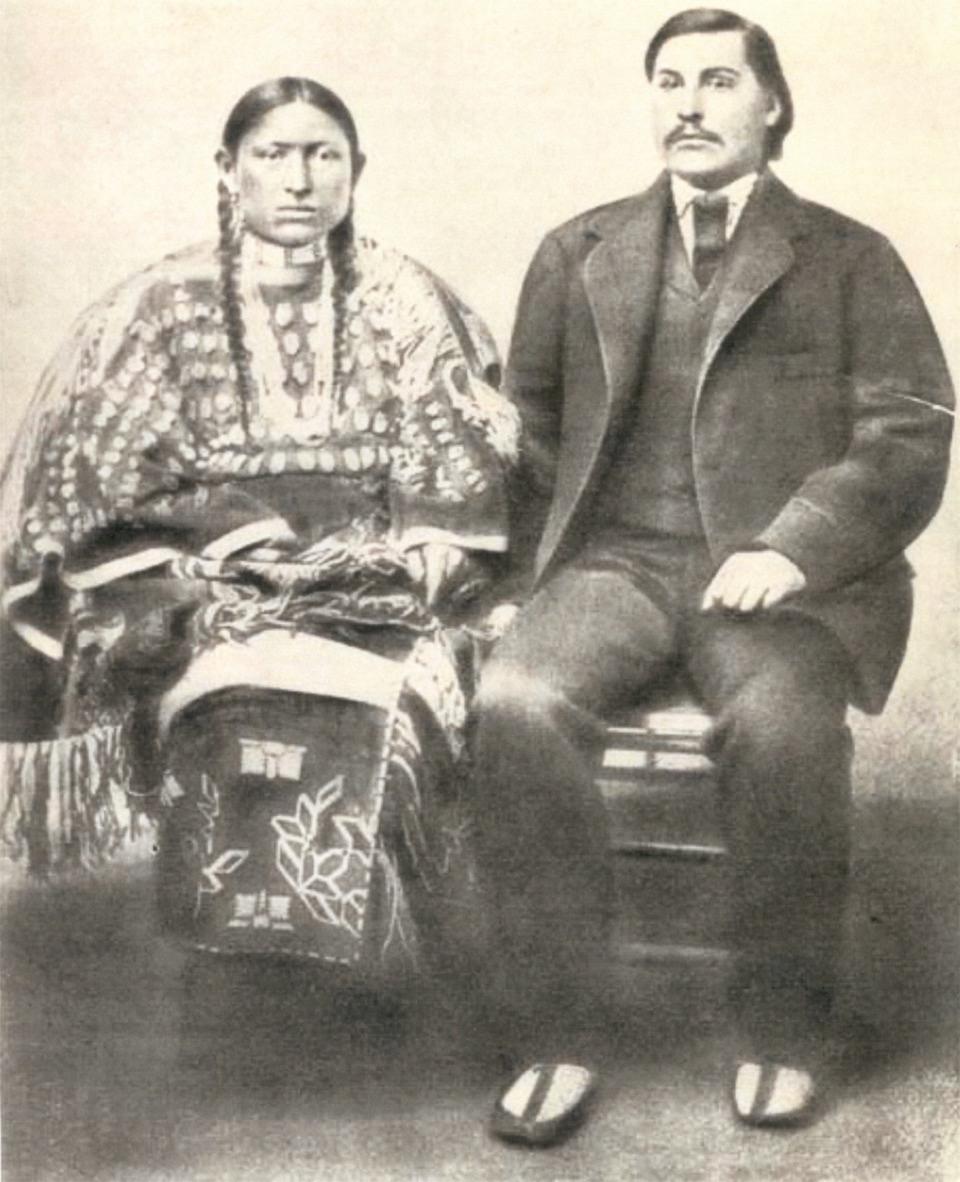

Image

Sawyers began negotiations with the tribe with Cheyenne George Bent interpreting.[6] In exchange for a wagon load of supplies, the Indians agreed to allow Sawyers safe passage. This agreement, however, didn’t please everyone. The rivalry between Sawyers and Captain Williford flared, because some of the soldiers did not feel it was right to “buy off the hostiles.” In his own report, Sawyers noted, the military escort “were discontented with this treaty, but were restrained by the majority from fighting.”

Peace did not last long. Sawyers next reported that Pvts. Anthony Nelson and John Rouse[7] of the Dakota Cavalry “ventured out” among the Cheyenne, possibly to trade with the Indians. An argument broke out and “in the melee,” the privates “were shot.” In response, Sawyers’s men opened fire with their howitzers and killed several of the Indians’ ponies.

Remembering the event decades later, Holman wrote “it is presumable that the Indians had induced the two to go further out of bounds, and then just for devilish cruelty, they had murdered the Norwegian [Nelson].”

Sawyers’s men recovered Nelson’s body, but couldn’t find Rouse, leading Holman to speculate he was still alive and, “perhaps from fear of the same treatment, the Mexican [Rouse] had joined [the Cheyenne].” Griggs was also certain Rouse had deserted: “there were no doubt entertained by the cavalry that he had deserted to the enemy.”[8]

A salvo fired from the two howitzers bought Sawyers’s men some space and they moved from Bonepile Creek to return to Caballo Creek. Sawyers sent out a scouting party to determine Gen. Connor’s location and see if the Army would send relief. In his report, Sawyers notes Williford was growing “faint hearted,” and pressing to abandon the expedition and make for the safety of Fort Laramie.

From the evenings of Aug. 16 through Aug. 18, they remained corralled at Caballo Creek. During this time, the Cheyennes made occasional runs for the livestock. Sawyers’s scouting party returned on Aug. 19. Having ridden 150 miles in 50 hours, they reported Gen. Connor had crossed the Powder River with a large expedition. More important to Sawyers, the Cheyenne were moving north, leaving the road south of Pumpkin Buttes clear.

Image

Crazy Woman Skirmish

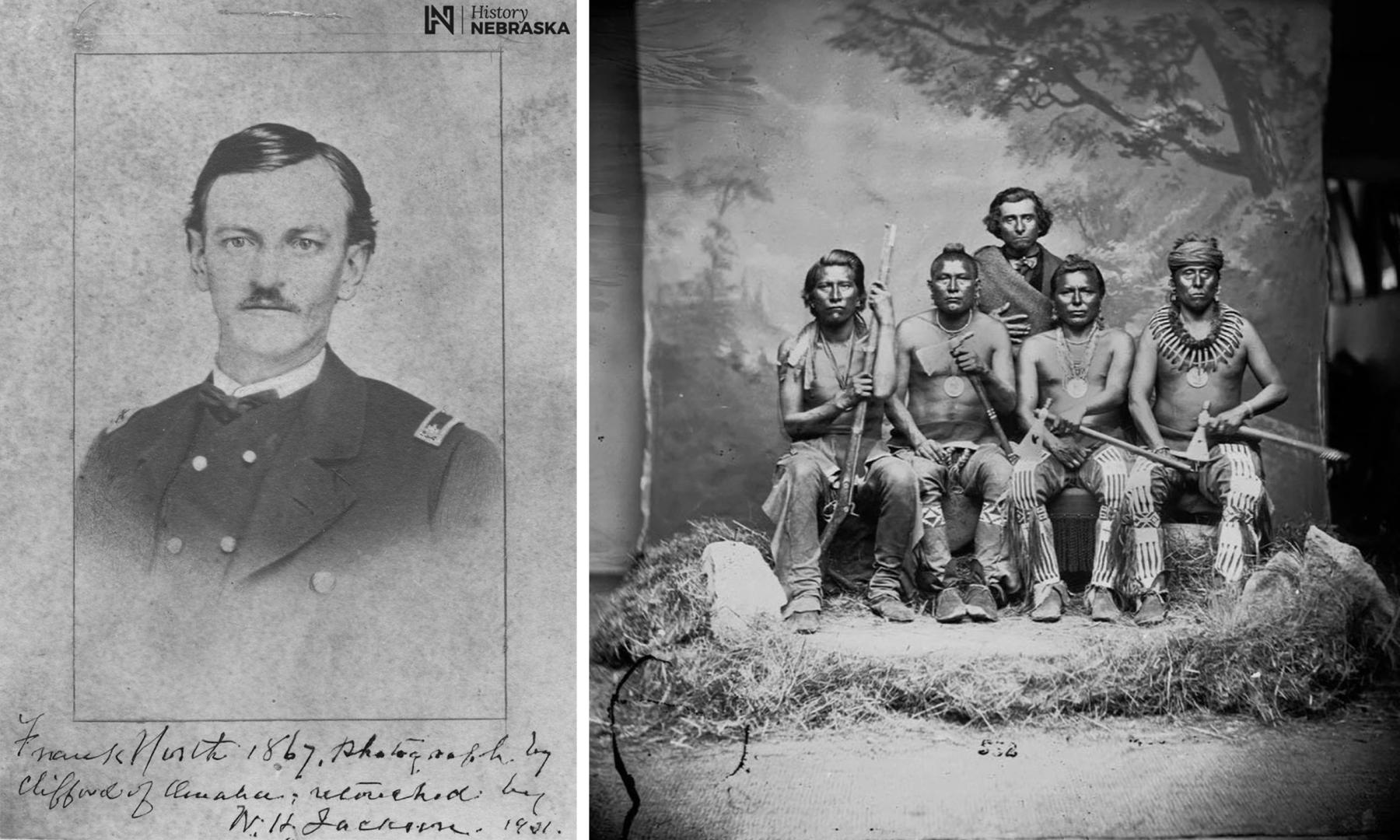

Unknown to Sawyers, events from Connor’s expedition triggered the northward movement of the Cheyenne. On Aug. 13—the same day the Cheyennes killed Hedges at Bonepile Creek—Connor’s Pawnee scouts, led by Capt. Frank J. North, spotted another group of Cheyenne warriors at Crazy Woman Creek. A skirmish ensued in which North’s horse was shot out from under him and several Cheyennes were wounded. North’s men followed the Cheyennes northeast down Crazy Woman to the Powder River, catching up on Aug. 16. The Cheyennes mistook North’s Pawnees for a party of Cheyenne warriors—possibly the Cheyenne harassing Sawyers. North and his scouts attacked the Cheyenne village and killed 24 Native Americans, including George Bent’s stepmother, Yellow Woman.

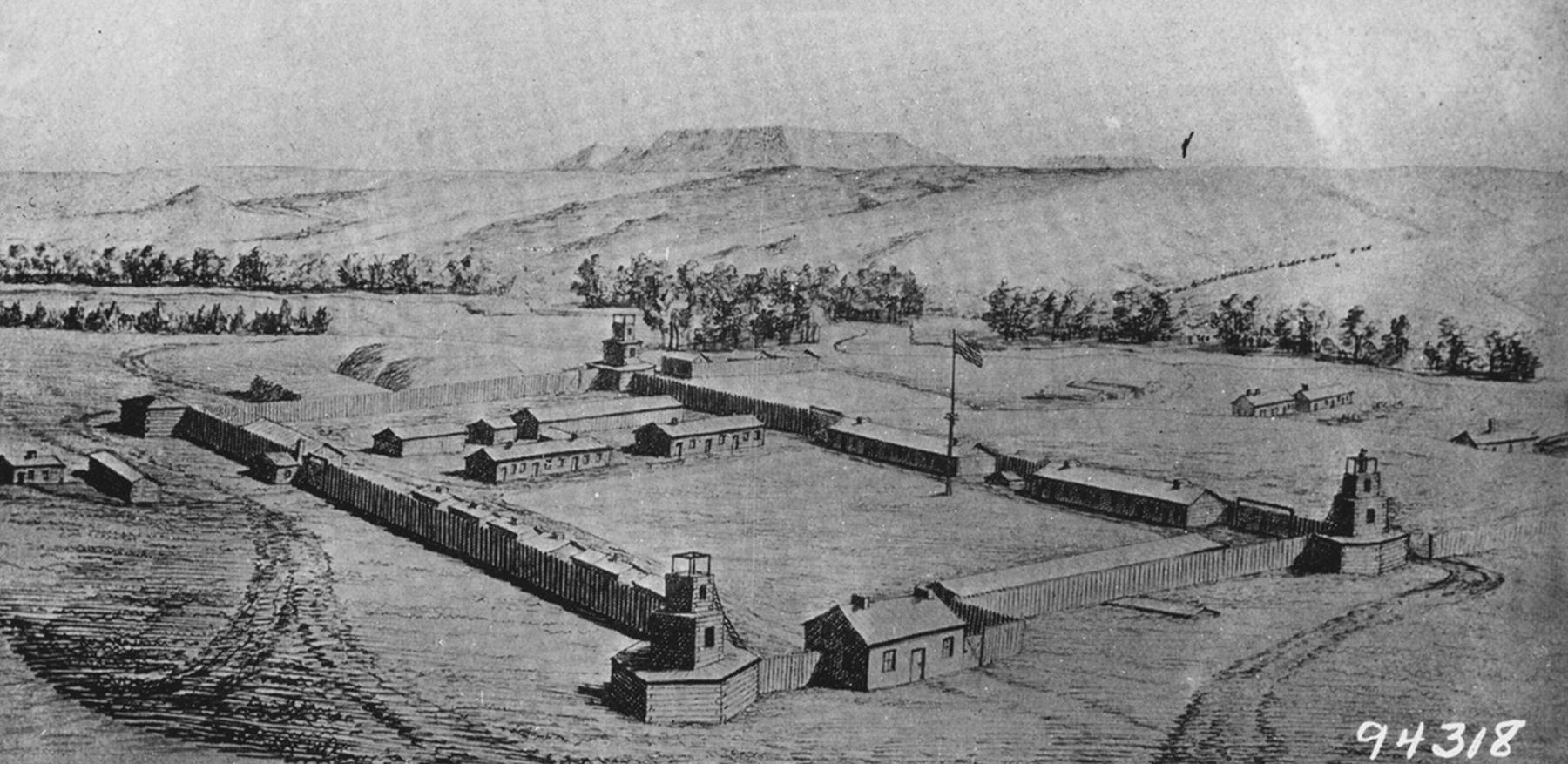

With the Cheyenne moving north, Sawyers and his party marched south of the Pumpkin Buttes unmolested. They reached the Powder River and camped one mile south of the newly established Fort Reno on Aug. 24.[9] Sawyers and Williford could now contact Gen. Connor. Connor ordered Williford to remain at Reno to assume command of the post, while his men were to be mustered out of service with the end of their enlistments. As a replacement, Connor ordered the 6th Michigan Volunteer Cavalry escort Sawyers on north up the Bozeman Trail.

Sawyers’s expedition continued north, crossing Crazy Woman Creek on Aug. 26. They reached Clear Creek by present Buffalo, Wyoming on Aug. 28 and passed by Lake De Smet on Aug. 29, unaware that a battle was underway 40 miles to the north.[10]

Image

Battle of the Tongue River and Sawyers’s Fight

On Aug. 28, Connor’s Pawnee scouts, along with guide Jim Bridger, saw smoke from an Arapaho village on the horizon. The next morning, Aug. 29, near present Ranchester, Wyoming, Connor’s men took Black Bear’s village by surprise. During the Battle of Tongue River, two of Connor’s men were killed and six wounded while the Arapaho lost between 35 and 63, including many women and children. As with Capt. North’s fight with the Cheyenne on Crazy Woman Creek, Connor’s battle with the Arapaho had ramifications for Sawyers’s expedition.

Sawyers’s party, meanwhile, made its way along the Bozeman Trail to the Tongue River, and on Aug. 31 Sawyers reported that Capt. Osmer F. Cole from the 6th Michigan escort was “surrounded and killed by Indians while scouting ahead.” The next day, Arapahos attacked the rear guard and teamster James Dilleland and emigrant E.G. Merrill were both shot and mortally wounded.

On Sept. 2, Sawyers’s party once again woke to the sight of Indians surrounding their camp with between 250 and 300 Arapahos around them. Under a white flag, Sawyers met with the Arapahos. The two parties agreed to send three men each to find Gen. Connor. The Arapahos hoped Connor would return the ponies his men stole in the raid on their village and Sawyers’s men hoped to convince Connor to send reinforcements.

For nearly two weeks, Sawyers’s expedition remained at Tongue River near present Dayton, Wyoming, in a kind of standoff with the Arapahos. Complicating matters, the members of the expedition knew they would lose the military escort if they pressed on, as the 6th Michigan had orders from Gen. Connor not to cross the Bighorn River some 50 miles ahead. Fearing the loss of the escort, the civilian party refused to travel any farther. With Sawyers’s leadership in disarray, the civilian men voted to remove him from command, despite his protest that they were acting “impulsively.”

It seems likely that the seeds of the rebellion were planted in the expedition’s makeup, as Sawyers struggled to maintain overall command of a mix of civilians and soldiers. This was highlighted in the first half of the journey in the feud between Sawyers and Williford. Now, Sawyers lacked the authority to order the 6th Michigan onward, setting the stage for the civilians in the expedition to question his leadership and remove him from command.

With Sawyers no longer in charge, the party voted to turn around and head back south to Fort Reno. As they were beginning their return, Company L, 2nd California Cavalry under Capt. Albert Brown arrived as a relief party sent by Gen. Connor —and the Arapahos departed.

Upon learning of the mutiny against Sawyers, Captain Brown wished to have the mutineers executed for their crime. According to Sawyers, he “begged” Brown “not to kill them” as there were too few men already. There may also have been a question of legality for such a harsh punishment—the mutineers were civilians, not soldiers. While the mutineers were spared, Captain Brown’s threats were enough to restore Sawyers to leadership.

With order and Sawyers restored, the expedition pressed on toward Montana Territory. They reached the Bighorn River on Sept. 19. As with the 6th Michigan, the 2nd California Cavalry were under orders not to proceed farther. However, Capt. Brown provided a seven-man detail, under Sgt. James Youcham, to escort Sawyers to Virginia City. After crossing the Bighorn, the party continued along to the Yellowstone River without incident and reached Virginia City on Oct. 12, 1865.

Aftermath

Although Sawyers’s expedition succeeded in reaching Virginia City, it failed in its wider mission to establish a road between Iowa and Montana. General Dodge wrote, “while its ostensible object was to survey and make a road through a country comparatively unknown, its real purpose seems to have been to take the [wagon] train through… instead of making a road.”

But the Indian attacks, dry conditions, attempted mutiny and Gen. Dodge’s scorn did not dissuade Sawyers from believing a Sioux City-Virginia City route feasible. He attempted again in 1866, succeeding in reaching Virginia City. The Montana Post reported, “no trouble was experienced in crossing streams, or on account of bad roads, loss of stock, or molestation from Indians.” Albert Holman also wrote that the second expedition recovered Nathanial Hedges’s body.

But this second successful expedition could not make the Sioux City-Virginia City route viable. Continued fighting between Native Americans and Whites drove the U.S. government to negotiate, and the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty proclaimed the Powder River Basin as “Unceded Indian Territory.” Furthermore, the relentless progress of the railroad, and the resulting greater ease of travel, made Sawyers’s Niobrara route, for two more decades, unnecessary.

Image

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, which in part made publication of this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Carrington, Margaret. Absaraka, Home of the Crows: A Military Wife's Journal Retelling Life on the Plains and Red Cloud's War. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 1868.

- “Colonel Sawyer [sic]” The Montana Post [Virginia City], Aug. 18, 1866, accessed Dec. 13, 2023 at chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/data/batches/mthi_grizzly_ver02/data/sn83025293/0029455533A/1866081801/0546.pdf.

- Doyle, Susan Badger. Journeys to the Land of Gold: Emigrant Diaries From the Bozeman Trail, 1863-1866. 2 vols. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2000. (Hereafter MHSP)

- Griggs, John Colby. “A Galvanized Yankee along the Niobrara River.” Edited by R. Eli Paul. Nebraska History 70, no. 2 (1989): 146-157, accessed Dec. 13, 2023 at history.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/doc_publications_NH1989Niob_Ynkee.pdf.

- Holman, Albert M. Pioneering in the Northwest: Niobrara-Virginia City Wagon Road. Sioux City, Iowa: Deitch & Lamar Co., 1924.

- Lee, Corwin M. “C. M. Lee Diary.” In Journeys to the Land of Gold: Emigrant Diaries From the Bozeman Trail, 1863-1866. Edited by Susan Badger Doyle, 382-419. MHSP, 2000.

- “Niobrarah [sic] and Virginia City Wagon Road.” The Montana Post [Virginia City], Oct. 28, 1865, accessed Dec. 13, 2023, at chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025293/1865-10-28/ed-1/seq-4/.

- Sawyers, James A. “James A. Sawyers Diary.” In Journeys to the Land of Gold: Emigrant Diaries From the Bozeman Trail, 1863-1866. Edited by Susan Badger Doyle, 355-370. MHSP, 2000.

- ______________. Wagon Road from Niobrara to Virginia City. Report prepared for Secretary of the Interior James Harlan. HR Ex. Doc. 58. 39th Congress, 1st Session, March 5, 1866, accessed Dec. 13, 2023 at babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012370816&view=1up&seq=143.

- Smith, Lewis H. “Lewis H. Smith Diary.” In Journeys to the Land of Gold: Emigrant Diaries From the Bozeman Trail, 1863-1866. Edited by Susan Badger Doyle, 371-382. MHSP, 2000.

- United States Senate. To provide for the construction of certain wagon roads in the Territories of Idaho, Montana, Dakota, and Nebraska. S 472. 38th Congress, 2nd Session. Feb. 24, 1865, accessed Dec. 13, 2023 at www.congress.gov/bill/38th-congress/senate-bill/472/text?s=5&r=419.

- United States House of Representatives. To provide for the construction of a wagon road from Columbus, Nebraska, to Virginia City, Montana Territory. HR 539. 39th Congress, 1st Session. April 30, 1866, accessed Dec. 13, 2023 at memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llhb&fileName=039/llhb039.db&recNum=1097. (To see HR 539, at the top left of this page, where there are two small rectangles, “Turn to bill,” and another with a number in it, enter 539 and click on “turn to bill.”

- “Virginia City and Niobrarah [sic] Wagon Road.” The Montana Post [Virginia City], Oct. 14, 1865, accessed Dec. 13, 2023 at chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025293/1865-10-14/ed-1/seq-2/.

Secondary Sources

Books

- Coutant, Charles Griffin. The History of Wyoming: From the Earliest Known Discoveries. 3 vols. Laramie, Wyoming: Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, 1899.

- Grinnell, George Bird. The Fighting Cheyennes. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1915.

- Hafen, LeRoy R. and Ann W. Hafen. Powder River Campaigns and Sawyers Expedition of 1965. Glendale, California: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1961.

- Johnson, Dorothy M. The Bloody Bozeman: The Perilous Trail to Montana's Gold. Missoula: Montana Press Publishing Co., 1983.

- McChristian, Douglas C. Fort Laramie: Military Bastion on the High Plains. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

- McDermott, John D. Circle of Fire: The Indian War of 1865. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2003.

- Wagner, David E. Patrick Connor’s War: The 1865 Powder River Indian Expedition. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Articles

- Doyle, Susan Badger. “The Bozeman Trail, 1963-1868.” Annals of Wyoming 70, no. 2 (Spring 1998): 3-11, accessed Dec. 13, 2023, at archive.org/details/annalsofwyom70141998wyom/page/n56/mode/1up.

- Edwards, Elsa Spear. “A Fifteen Day Fight on Tongue River.” Annals of Wyoming 10, no. 2 (April 1938): 51-58, accessed Dec. 22, 2023, at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom10141938wyom/page/50/mode/2up?v….

- Hampton, H.D. “The Powder River Expedition 1865” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 14, no. 4 (Autumn 1964): 2–15. JSTOR, accessed Oct. 12, 2023, at www.jstor.org/stable/4516884. Available to patrons at most public libraries.

- Myers, Alice V. “Wagon Roads West: The Sawyers Expeditions of 1865, 1866.” Annals of Iowa 23, no. 3 (Winter 1942): 213-237, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at pubs.lib.uiowa.edu/annals-of-iowa/article/id/13634/download/pdf/.

- Schneider, Edward A., and James A. Lowe. “Rifle Pits on the Plains: Data Recover Investigations at the Caballo Creek Rifle Pit Site (48CA271), Campbell County, Wyoming.” Report by TRC Mariah Associates Inc. for Amax Coal West, Inc., October 1997.

Websites

- Alexander, Kathy. “Powder River War, Wyoming.” Legends of America: A Travel Site for the Nostalgic & Historic Minded. Last modified April 2022; accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.legendsofamerica.com/powder-river-war-wyoming.

- Drew, Marilyn J. “A Brief History of the Bozeman Trail.” Nov. 20, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/brief-history-bozeman-trail.

- Gaster, Patricia C. “Major North’s Buffalo Hunt Ended by a Blizzard.” History Nebraska accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at history.nebraska.gov/major-norths-buffalo-hunt-ended-by-a-blizzard.

- “George Willerford.” FamilySearch. Accessed October 26, 2023 at www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MX4K-HSY.

- “George W. Williford (1836-1866).” WikiTree. Last modified Oct. 16, 2023, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wikitree.com/wiki/Williford-323.

- Hein, Ellis. “Connor’s Powder River Expedition of 1865.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/connors-powder-river-expedition-1865.

- Hein, Ellis. “The Battles of Platte Bridge Station and Red Buttes.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/battles-platte-bridge-station-and-red-buttes

- Linn, Linda. “Sawyers, James A.” IAGenWeb Project. Sept. 24, 2010, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at iagenweb.org/boards/woodbury/biographies/index.cgi?read=300082.

- Nash, Jeff. “James Alexander Sawyers.” Find A Grave. Accessed October 26, 2023 at www.findagrave.com/memorial/186805701/james-alexander-sawyers.

- “Newell M Sawyers.” Find A Grave.com, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.findagrave.com/memorial/196429387/newell-m-sawyers.

- Nelson, Robert L. “Sawyers, James A. (1824-1898).” Old Soldier: The Story of the Grand Army of the Republic in Santa Cruz County. Santa Cruz, CA: The Museum of Art & History, SCPL Local History, 2004, accessed Dec. 14, 2023, at history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/133854.

- Nottage, James H. “Rivers, Mountains and Plains: The Raynolds Expedition of 1859-1860.” May 31, 2023. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/rivers-mountains-and-plains-raynolds-expedition-1859-1860.

- Rea, Tom. “Gathering the Tribes: The Cheyennes Come Together after Sand Creek.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec, 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/gathering-tribes-cheyennes-come-together-after-sand-creek.

- Van Pelt, Lori, and WyomingHeritage.org. “Fort Reno and Cantonment Reno: Indian Wars Outposts on Powder River.” Nov. 17, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/fort-reno-and-cantonment-reno.

- WyomingHeritage.org. “Connor Battlefield.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Dec. 14, 2023 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/connor-battlefield.

Illustrations

- The photos of James and Newell Sawyers are from the Sioux City Public Museum via the Campbell County Rockpile Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Capt. George Williford is from WikiTree.com. Used with thanks.

- The map, the drone photo of the site of the fight on Bonepile Creek and the photo looking toward the Bighorns from a location near the site of the Arapaho attack on the Sawyers Expedition are by the author. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the rifle pits is from the Campbell County Rockpile Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of George Bent and Magpie is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- Anton Shonborn’s drawing of Fort Reno is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, via the Campbell County Rockpile Museum. Used with permission and thanks,

- The photo of Frank North is from History Nebraska. Used with thanks. The photo was taken by Clifford of Omaha and much later retouched by William Henry Jackson.

- The William Henry Jackson photo of Pawnee scouts and their French/Pawnee interpreter is from Reddit, with no other source given. Used with thanks. The photo dates from around 1870, and was probably taken in Jackson’s studio in Omaha, Nebraska. We used it instead of a more commonly reproduced version from Wikipedia, as the Reddit version shows the straw bales and more of Jackson’s studio.

[1] These were “Galvanized Yankees,” who were Southern soldiers captured in battle. Instead of housing them in prisoner of war camps, which required resources and manpower, the Union offered their Confederate prisoners an alternative. Swear allegiance once again to the United States and join the Union Army. The term galvanized comes from metal work, when one metal is coated in another. Often zinc is used to coat steel to protect it. In the process the surface of the metal is altered, but underneath the coating the original metal is unchanged. Because they were Southerners with only a new coating, the US did not trust these Galvanized Yankees in fighting against their former Confederacy. So, the US sent these soldiers West to fight the “hostile” Indians.

[2] Sawyers referred to the Belle Fouche River as the “Northern Cheyenne River.”

[3] Connor’s Powder River Expedition included three columns. The Right Column, led by Colonel Nelson D. Cole, left Omaha, Nebraska and followed the Loup River westward. The Center Column, led by Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Walker, left Fort Laramie northward and skirted the Black Hills. Connor himself traveled with the Left “west” Column from Fort Laramie into the Powder River country.

[4] The Pumpkin Buttes – or Gourd Hills as the native Lakota called them for the gourd shaped rocks around the base – are a prominent geologic feature in southern Campbell County where Native Americans hunted bison for thousands of years.

[5] Emphasis original.

[6] Both Lee and Holman referrer to George Bent as a “Choctaw Indian.” Bent was a “Suhtai” in his native Southern Cheyenne language, which must have sounded like “Choctaw” to the Americans.

[7] Sawyers’s spells the name as “John Rawze.” Griggs spells it “Luse.”

[8] Holman places the incident as taking place on Aug. 20. Sawyers, Smith, Griggs and Lee all place the incident on Aug. 15.

[9] In an attempt to avoid confusion, the name “Fort Reno” is used throughout this article. General Connor established the fort on Aug. 15, 1865, the very same day Sawyers awoke to find “500 to 600” Indians on the hills around him. Initially, the fort on the Powder River was named Fort Connor after the General who established it. The name was changed in November 1865 to Fort Reno. A common misconception is that Fort Reno was named in honor of Major Marcus Reno who was at the Little Bighorn Battle. This of course is incorrect, as the Fort was named Reno in 1865 and the Little Bighorn Battle was in June 1876. Fort Reno’s namesake is Major General Jesse Lee Reno who was killed at the Civil War Battle of South Mountain, Maryland. Situated on the Powder River near Sussex, Wyoming in modern-day Johnson County, little remains of Fort Reno. It was abandoned and burned to the ground by Cheyenne warriors after the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

[10] In an attempt to avoid confusion, the name “Fort Reno” is used throughout this article. General Connor established the fort on Aug. 15, 1865, the very same day Sawyers awoke to find “500 to 600” Indians on the hills around him. Initially, the fort on the Powder River was named Fort Connor after the General who established it. The name was changed in November 1865 to Fort Reno. A common misconception is that Fort Reno was named in honor of Major Marcus Reno who was at the Little Bighorn Battle. This of course is incorrect, as the Fort was named Reno in 1865 and the Little Bighorn Battle was in June 1876. Fort Reno’s namesake is Major General Jesse Lee Reno who was killed at the Civil War Battle of South Mountain, Maryland. Situated on the Powder River near Sussex, Wyoming in modern-day Johnson County, little remains of Fort Reno. It was abandoned after the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, and Cheyenne warriors burned it to the ground.