- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Powder River Basin: A Natural History

The Powder River Basin: A Natural History

“This story of Powder River is—in reality—the story of grass,” Struthers Burt wrote in his lyrical 1938 book Powder River: Let ‘er Buck. “The search for it. The fight for it. The slow disappearance of it.”

Grass has translated to the economic basis for cultures in western North America for 10,000 years or more. Meat, leather and wool came first from free-roaming bison and other game and recently from domesticated cattle and sheep. Tens of millions of plains bison once roamed between Alberta and Florida.

But Burt didn’t consider another form of vegetation that has since become an even bigger piece of the Powder River Basin story: plants buried millions of years that have cured into thick coal seams underground. Today northeast Wyoming produces 40 percent of the nation’s coal, which is burned to generate about a fifth of the country’s electricity. The region is home to the eight largest U.S. coalmines. About 13.9 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from burning Powder River Basin coal.

This industry also powers a substantial portion of Wyoming’s economy. In 2008, the mines directly employed more than 6,800 workers. In 2010, Campbell County, where most of the Powder River Basin coal mines are located, produced nearly $4.5 billion worth of taxable minerals, more than any other Wyoming county.

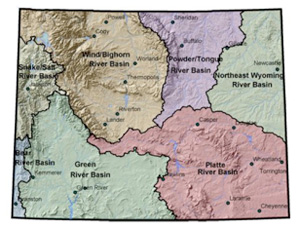

Generally the Powder River Basin refers to the lower elevation lands reaching from the Bighorn Mountains in north central Wyoming to the Black Hills on the Wyoming/South Dakota border, even though this region also includes the watersheds of the Tongue, Little Missouri, Belle Fourche and Cheyenne rivers, tributaries of the Yellowstone and Missouri.

People, meanwhile, have lived in the Powder River Basin for thousands of years. Archaeologists unearthed huge bison bones from an arroyo trap on the Hawken Ranch south of Sundance, Wyo., in the 1970s and dated them to more than 6,000 years ago. Several other similar sites are scattered across the northeast corner of Wyoming. Before horses, hunters relied on geography and even elaborate wood corrals to trap and slaughter their prey. One such site, the Vore Buffalo Jump east of Sundance holds bones from an estimated tens of thousands of bison that died there over the span of hundreds of years.

In the 18th century, the Powder River Basin was home to the Crow Indians, and towards the turn of the 19th century, Oglala and Brulé Lakota tribes arrived from Minnesota. The Minniconjou, Hunkpapa and Sans Arc Lakota followed them in the 1820s, around the time bison were driven to extinction east of the Mississippi River. The Lakota were formidable warriors and excellent horse riders, while the Crow were reputed stealthy horse thieves. The two tribes skirmished over the Powder River country, with the Crow mostly occupying the Bighorn Mountains, while the Lakota controlled the plains. Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, allies of the Lakota, hunted in southeast Wyoming.

In 1808, fur trapper Edward Rose—part Cherokee, part black and part white—arrived in what’s now southern Montana and lived with the Crow for several years. In 1811, he met Wilson Price Hunt on his way west to join fur-trade entrepreneur John Jacob Astor’s ship at the mouth of the Columbia River. Rose guided Hunt south along the face of the Big Horn Mountains to Clear Creek and the headwaters of the Powder River, but when Hunt surmised that Rose planned to steal his horses, he paid the man off and started on without him. Eventually, however, Hunt needed the help of Rose and some Crow friends after all, to find his way over the Bighorns.

Jim Beckwourth, by some accounts the son of Englishman Sir Jennings Beckwith and a slave woman, came to the West from Virginia at age 24 with William Ashley to trap furs. In 1826, Beckwourth settled among the Crow, with whom he lived for six years before exploring more of Wyoming and moving on to California.

The first lasting log buildings in Wyoming—other than the Astorians’ temporary cabins on the North Platte River in 1812—were Antonio Matero’s trading post cabins, the “Portuguese Houses,” built on the banks of the Powder River near present Sussex, Wyo., in 1834. Matero traded with the Indians for beaver pelts from the Big Horns until a brigade of trappers led by Jim Bridger drove him out of the Powder River country. Another outsider who came to the area at this time was the missionary priest, Pierre-Jean De Smet, who befriended the Lakota in Wyoming and other tribes throughout the Rocky Mountain region.

The Fort Laramie treaty of 1851, designed primarily to keep tribes from bothering emigrants on the Oregon/California/Mormon Trail, set aside land for the Crow Nation west of the Powder River and the Lakota Nation to its east. For many years, this country was largely unvisited by white people. It wasn’t until 1859 that Capt. W. F. Raynolds of the U. S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers explored the Powder River Basin to map and describe—in uncomplimentary terms—the many forks of the Powder and Tongue rivers.

In 1863, John Bozeman established the Bozeman Trail up the east side of the Bighorns as a route for settlers and prospectors from the North Platte River emigrant trails to newly discovered gold fields in Montana. Meanwhile, Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota Indians were converging on the rich hunting grounds of the Powder River country. During a treaty meeting at Fort Laramie in 1866 to discuss terms of safe passage for travelers on the Bozeman Trail, the U. S. War Department sent Col. Henry B. Carrington into the Powder River Basin at the head of 700 troops.

This angered Red Cloud, leader of the Oglala Lakota. Over the next few years Red Cloud, accompanied by Crazy Horse and other warriors, attacked U.S. military troops in the Powder River basin several times, notably at Fort Phil Kearny near present day Story, Wyo. Finally, the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty granted the whole northeast corner of what is now Wyoming to the Indians, who burned the hated forts the army had built along the Bozeman Trail to the ground as the troops marched away.

Things were quiet in the Powder River Basin for the next several years, but outside changes continued that would eventually reach the ceded lands. In 1870, 40,000 cattle came into southeastern Wyoming Territory from Texas. Meanwhile, bison were being slaughtered systematically in Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma Territory.

Tensions rose again in the Powder River Basin after Gen. George Armstrong Custer led a large party that discovered gold in the Black Hills in 1874. Prospectors clamored for the U.S. government to acquire the land from the Indians, but Lakota leaders did not accept the U.S. government’s offer to buy them for $25,000. In frustration President Ulysses Grant required that all the Indians move to their respective agencies or reservations by Jan. 31, 1876, or be subject to military action.

As the summer of 1876 approached, three armies moved toward the northern Bighorns seeking Indians who hadn’t moved to the agencies: Gen. George Crook followed the Bozeman Trail from the south; Col. John Gibbon moved in from the west; and Gen. Alfred H. Terry, accompanied by Custer, came from the east. This campaign led to two battles in Montana, Crook’s on the Rosebud, where he claimed victory but from which he retreated afterward, and Custer’s on the Little Big Horn, the army’s worst defeat in the frontier West.

Following these battles, a U.S. government peace commission gathered signatures on a new agreement, contrary to the 1868 treaty, to take the Powder River country from the Lakota. The following spring, Crazy Horse surrendered, and a few months later a soldier stabbed him to death with a bayonet in a scuffle at the Spotted Tail Agency in Nebraska. Dull Knife and the Northern Cheyennes were exiled to Oklahoma Territory. Sitting Bull lived at a South Dakota agency until 1890 when he was shot while being arrested for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance. The 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota was the last major conflict of the Indian wars.

Meanwhile, in 1878, Cantonment Reno, an army supply base at the Bozeman Trail crossing of the Powder River, had been renamed Fort McKinney and moved to a site on Clear Creek officially opening the Powder River country to white settlers. The town of Buffalo soon sprang up near the fort.

By 1883, only about 100 bison remained on the northern plains and 200 more in Yellowstone National Park. Cattle were trailed up from the Gulf of Mexico to fatten on the Powder River grass. Cowboys poured into the Powder River country to work at the 20-some established cattle companies worth a cumulative $12 million. In 1885, the Powder River Cattle Company may have owned more than 50,000 cows.

The cattle boom didn’t last long. The brutal winter of 1886-1887 killed perhaps 15 percent of the cattle in Wyoming, though some outfits reported losses far higher. A year later, sheep started trailing into the Powder River area, and smaller independent cattle operations started to overrun the big cattle barons.

In 1892, a contingent of 50 “invaders” from Texas and Cheyenne rode into Johnson County and murdered some ranch hands. President Benjamin Harrison authorized the use of U.S. troops stationed at Fort McKinney to settle the infamous incident, known as the Johnson County War. Struthers Burt sympathized with the “big owners,” who, he wrote, “were in the same position the Sioux had been fourteen years before.… They were fighting for a magnificent way of living, a generous and heroic and historic method of making your livelihood.” More recent historians such as Helena Huntington Smith and John W. Davis have seen the cattle barons as thugs willing to resort to murder when confronted by fast-changing economic and political forces beyond their control.

Meanwhile, settlements in Wyoming like Sheridan, Buffalo and Kaycee sprang up and grew. Dietz, the oldest Sheridan coal camp, opened in 1893. The town of Gillette was founded at the arrival of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad in 1891. The railroad reached Sheridan in 1892, which was the terminus until it continued on to Montana in 1894.

Beginning in the 1890s, outlaw gangs used hideouts in the Hole-in-the-Wall area at the south end of the Bighorns, where characters such as Kid Curry, the Sundance Kid, Flat-Nosed George Currie, Tom O’Day and perhaps Butch Cassidy hid between robberies. Cattle rustlers and horse thieves also escaped into the canyons and rough terrain to evade law enforcement. After Kid Curry led a robbery of a Union Pacific train near Wilcox, Wyo., in 1899, U.S. marshals and railroad detectives pursued his gang into the Hole-in-the-Wall country, where friends provided fresh horses and the posse lost the trail.

Northeast Wyoming saw prosperity and growth during the first decade of the 20th century. The Sheridan flourmill was built in 1903. In 1904 the Eaton brothers set up Wyoming’s first dude ranch east of Sheridan. Devil’s Tower became the first National Monument under designation by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906. A 1909 revision to the Homestead Act brought dryland farmers to northeast Wyoming by doubling the amount of free land they could claim from the government.

Polo came to the foothills of the Bighorns in the 1890s and flourished there in the early 20th century. In 1898, Scotsman Malcolm Moncreiffe built a polo field and thoroughbred horse-breeding operation in Big Horn. In the 1920s, the Circle V Polo Company in Big Horn created by Goelet Gallatin was the world’s best polo operation, according to historian and polo aficionado Sam Morton. Today, the Flying H Polo Club in Big Horn is one of only three in the United States to offer high goal polo, attracting professional teams from all over the world.

The 1920s and 1930s, however, brought economic depression and drought to Wyoming. Cattle numbers declined, railroad workers held strikes and banks closed. In 1922, a scandal over oil leases around Teapot Dome on the south end of the Powder River Basin led to the jailing of U. S. Secretary of Interior Albert Fall and, briefly, of oilman Harry Sinclair.

Even as more oil discoveries were made and coal mines opened up in the Powder River Basin, agriculture remained the main occupation until the 1970s. After World War II, Wyoming enjoyed good times along with the nation’s rising prosperity. However, the state’s population grew more slowly than the rest of the country, the number of people involved in agriculture declined, and many Wyoming-educated graduates moved out of state.

The Powder River Basin coal boom started in the 1970s. The biggest mine by production volume, Black Thunder, opened in 1977. The company town of Wright sprang up at nearby Reno Junction, beginning with the 108-unit Cottonwood Mobile Home Park. As of 2012 there are 13 operating coalmines in the Powder River Basin in Wyoming. The Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroads carry trains full of Powder River Basin coal to power plants from Washington to New York and many states in between, with most volume going to Texas and the Midwest.

Another kind of boom kicked off in the 1990s when energy developers figured out how to extract, transport and market coalbed methane, a form of natural gas in underground coal seams. Wyoming now produces about a fifth of the nation’s domestic coalbed methane. More than 20,000 wells were drilled in this area during the 1990s and early 2000s, many on public land, but others on private ranchland where the federal government owns the mineral rights, a contentious situation termed “split estate.”

Roads, well pads and other infrastructure have altered the landscape while water released from deep underground to relieve pressure and let the gas escape contaminates freshwater sources due to its salinity. New drilling slowed when natural gas prices dipped around the end of the first decade of the 21st century. Still, Powder River Basin coalbed methane contributes hundreds of millions to county, state and federal taxes each year.

Today, energy development far outpaces ranching as a source of wealth and income in the Powder River Basin, although many residents in this part of the state still practice agriculture and identify with their cattle- and sheep-ranching roots. They still rely on the Powder River grass to fatten their livestock. Professional bareback rider and country music star Chris LeDoux, who died of cancer in 2005 and was inducted into the ProRodeo Hall of Fame in 2006, captured the spirit of the Powder River country in many of his songs.

Where the river winds from the Bighorns up above

And the clear moon shines on the prairie that I love

It’s the closest place to heaven that this cowboy’s ever known

I’m going back to my Powder River home.

Resources

- Brown, Dee. Fort Phil Kearney: An American Saga. New York: Van Rees Press, 1962.

- Bureau of Land Management High Plains District Office. “Powder River Basin Coal.” Accessed 1/16/12 at: http://www.blm.gov/wy/st/en/programs/energy/Coal_Resources/PRB_Coal.html.

- Burt, Struthers. Powder River: Let ‘er Buck. The Rivers of America. New York: Rinehart & Company, Inc., 1938.

- Carswell, Cally. “Trouble in the Powder River Basin.” High Country News. Nov. 07, 2010. Accessed online 01/12/12 at: http://www.hcn.org/issues/42.19/trouble-in-the-prb.

- Frison, George C. Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains. New York: Academic Press, 1978.

- Gates, C. C., C. H. Freese, P. Gogan and M. Kotzman, eds. “American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010.” Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature. Accessed 12/11/11 at: http://www.iucn.org/?4750.

- “James Pierson Beckwourth, 1798-1866,” accessed 1/15/12 at http://www.beckwourth.org/Biography/index.html.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

- Moulton, Candy. “Wright.” Roadside History of Wyoming. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing, 1995, p. 341.

- Morton, Sam. “116 Years of Polo in Sheridan County.” Flying H Polo Club, Big Horn, Wyo. 2006. Accessed 12/17/11 at: http://www.flyinghpolo.com/history.htm.

- U. S. Congress. Senate. “Report of Captain W. F. Raynolds' Expedition to Explore the Headwaters of the Missouri & Yellowstone Rivers.” 40th Cong., 2d sess., 1867. S. Doc. 77. Accessed 12/17/11 at: http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~familyinformation/fpk/raynolds_rpt.html.

- Rea, Tom. The Hole in the Wall Ranch: A History. Greybull, Wyo.: Pronghorn Press, 2010, 39-44, 57-140.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Table 9. Major U.S. Coal Mines.” 2010 Annual Coal Report. Nov. 2011. Accessed 1/16/12 at: http://www.eia.gov/coal/annual/.

- Vaughn, J. W. The Reynolds Campaign on Powder River. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

- Wildlife Conservation Society. “American Bison Society: Bison Timeline.” Accessed 12/11/11 at: http://www.americanbisonsocietyonline.org/AboutUs/Timeline/tabid/308/Default.aspx.

Illustrations

- The Library of Congress photo of the Irigary Bridge over Powder River near Sussex, Wyo., was taken in 1982. The bridge was built in 1913.

- The map of Wyoming river basins is from the Wyoming Water Development Commission, used with thanks.

- The photo of the Black Thunder Mine is from Ecoflight. Used with thanks.