- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Fremont County, Wyoming

Fremont County, Wyoming

Fremont County consists primarily of the Wind River Valley in the western part of the Wyoming. It is bordered on the south and west by the Wind River Mountains and on the north by the Owl Creek Mountains. The county extends east over Beaver Rim into central Wyoming.

Early history

Indigenous people made frequent hunting visits to the area and in early historic times, beginning around 200 years ago, the valley was a favored bison hunting location when those animals became increasingly scarce on the Great Plains. But the valley was very much a disputed territory and hunting parties came with an understanding that they would likely have to fight to use the valley’s resources.

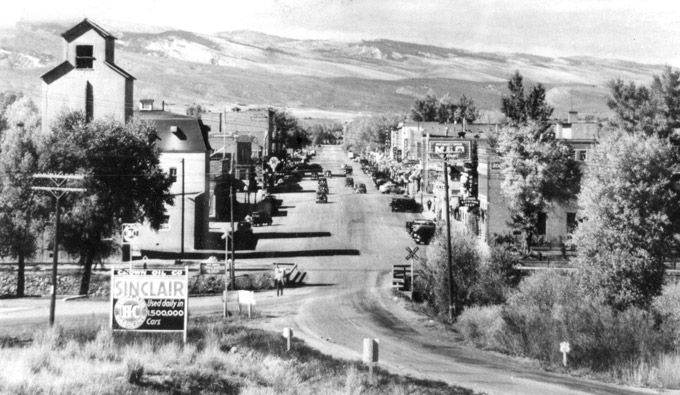

Image

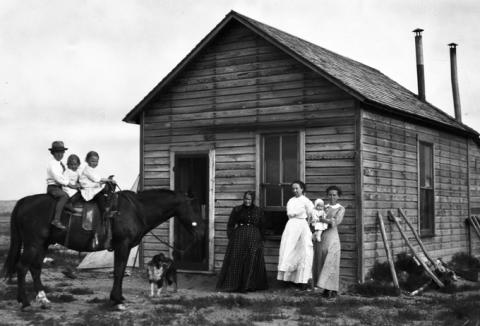

Permanent residents began coming to the area in the late 1860s. News of a gold discovery near South Pass in the late 1860s created excitement that attracted many who had only recently participated in the nation's Civil War. They came from all parts of the United States and beyond.

A Shoshone reservation

But even as prospectors and would-be mining entrepreneurs flocked to the area between the Sweetwater River and the southern end of the Wind River Mountains, representatives of the U.S. government were meeting with Eastern Shoshone Indians at Fort Bridger to discuss the establishment of a reservation for the people of that tribe.

The Shoshone had long wandered from the Great Basin eastward through South Pass to the Wind River Valley and beyond to hunt plains buffalo. By the 1840s and 1850s, though, they spent most of the time on the southwest side of the mountains in the Green River Valley and southwest into the Salt Lake Valley. Increasing conflicts with white settlers in those areas motivated the Shoshone to seek land they could call their own.

The U.S. government, recognizing that the coming construction of a transcontinental railroad across the southern part of Wyoming Territory would be opposed by some tribes and acknowledging that the Shoshone had established a reputation as a tribe that was less hostile than many others, saw advantage in situating the Shoshones in the Wind River Valley. There, they might serve as a buffer between the railroad and the more hostile Sioux and Crow tribes to the north.

By the time an agreement was reached in July 1868 for a treaty to establish a Shoshone Reservation that extended from the South Pass area northward across the Wind River Valley and over the Owl Creek Mountains into the Bighorn Basin, white gold miners were already creating the mining camps of South Pass City and Atlantic City on lands that were to be part of the reservation. And a small group of settlers had already set up homes in the Wind River Valley itself.

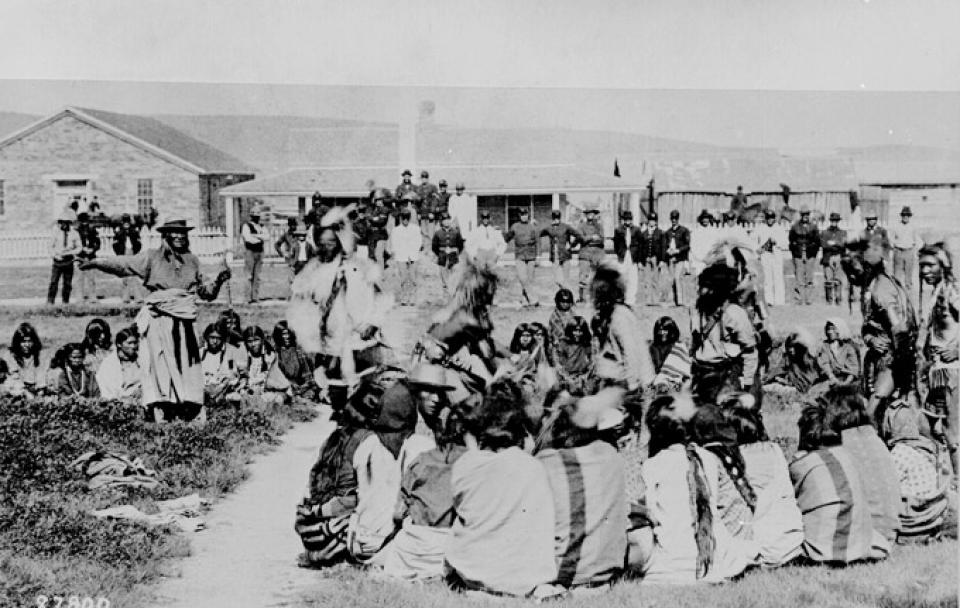

Those complications would be worked out in the years that followed, but the Shoshone refused to move into the valley until the government established a military outpost to provide protection against raiding parties of Sioux, Crow and Arapaho warriors. That outpost, established in 1869 on the site that had been known as Camp Augur, but which was now referred to as Camp Brown, was in the area where the town of Lander now stands.

In 1870 Camp Brown was moved a few miles north and west to the banks of the Little Wind River. In 1878 the post's name was changed to Fort Washakie, in honor of a Shoshone chief who was helpful to the government. The Wind River Indian Agency was located a short distance from the fort on the banks of Trout Creek.

Cattle and sheep

Up in the Sweetwater gold mining area, South Pass City quickly blossomed into a community of 2,000 or more citizens. There was even some talk that it might be a better site for Wyoming's capitol than Cheyenne. But that fizzled quickly as the supply of gold from the diggings declined and South Pass City residents started leaving. Some went to newer, more exciting mining areas. Some went down into the Wind River Valley to raise crops and livestock that could be sold to those working in the gold fields. Some just left.

Farther downstream on the Sweetwater, stockmen brought herds of cattle into the area. Iowa businessman John T. Stewart established the 71 Quarter Circle Ranch in the area that was famous among Oregon Trail emigrants as Three Crossings. Stewart started his cattle operation in the late 1870s and soon Stewart’s cattle and horses were ranging north to the southern end of the Bighorn Mountains and west, over Beaver Rim and far into the Wind River Valley. Many of Stewart’s cattle were purchased in Oregon and driven east along the emigrant trail.

James K. Moore, the first licensed Indian trader on the Shoshone reservation, began running cattle on the reservation with permission from Chief Washakie. One of the U.S. Army officers at Fort Washakie, Robert Torrey, operated a big cattle operation just off the reservation, on the north side of the Owl Creek Mountains.

Farther north, Otto Franc set up a cattle raising business on the Greybull River. Jules Lamoreaux’s home base for his cattle operations stood on a bluff overlooking the Middle Fork of the Popo Agie River and the site of early Lander. He was one of several men who ran cattle operations from headquarters in the Lander area.

As the 1870s passed, stockmen who made their living from sheep also arrived in the Wind River Valley and the Bighorn Basin. John D. Woodruff, frequently credited with bringing the first sheep into the area, came as a wolf hunter. Woodruff’s home was one of the first permanent residences in the Bighorn Basin.

Others were not far behind. Luther Morrison and his wife Lucy, who later achieved fame as the "Sheep Queen of Wyoming", trailed sheep from Idaho and set up operations in the Dry Creek area below Copper Mountain, north of present Shoshoni. John Brognard Okie, a young man from our nation's capital, borrowed money from his mother to buy a band of sheep and established himself and his herds on rangeland along Badwater Creek. There, in the 1890s he built the town of Lost Cabin and a sheep and business empire that rivaled some of the largest operations in Wyoming.

A new county

All of this took place in what was still Sweetwater County, but as more settlers came to the area, sentiment grew among people living around Lander that conducting business 125 miles to the south in the county seat at Green River was too difficult. Herman G. Nickerson of the Lander area led efforts in the territorial legislature to divide Sweetwater County and create a new county to the north with Lander as its county seat.

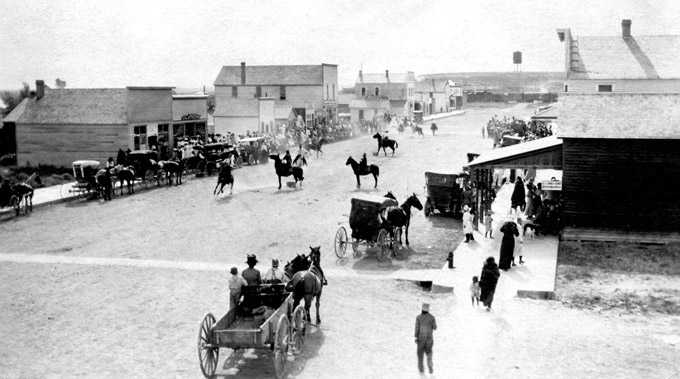

As noted previously, Lander was located in the area where Camp Augur and Camp Brown had existed. When the military post moved 16 miles northwest, some of the early residents stayed on and a town developed in the 1870s at the earlier site. But Lander was not officially incorporated until 1890.

Nickerson claimed to have served under the famed explorer and U.S. Army officer John C. Frémont during the Civil War. He convinced others that the new county, organized in 1884, should be named for Frémont. In its early years, Fremont County stretched more than 200 miles from the country south of South Pass and the Wind River Range all the way to the Montana border.

The Arapaho tribe and the Wind River Reservation

In the 1870s, changes occurred on the Indian reservation as well. The Arapaho tribe had long roamed the mountains and plains from Montana across eastern Wyoming to southern Colorado territories. The federal government made an attempt to settle them in Indian Territory--what would later become the state of Oklahoma--but only a portion of the Arapaho tribe made that move. The Northern Arapaho tribe continued to pressure the government for a reservation in Wyoming.

Finally, the U. S. government asked the Shoshone to allow the Arapaho to camp temporarily on their reservation lands. That short-term arrangement eventually became permanent. In 1878, The Arapahos established camps on the lower Little Wind River, and the Shoshone remained dominant around Fort Washakie. When the military garrison at Fort Washakie was terminated in 1909, most of the Indian agency functions were moved into other quarters used previously by the military. The Shoshone Reservation later became known as the Wind River Reservation.

From the 1870s through the first decade of the 20th century meanwhile, the federal government initiated negotiations with the Indians that shrank the size of the reservation and opened the ceded lands for other uses by non-Indians. The largest cession, in 1904, called for reservation lands north of Wind River to be turned over to the U.S. government in return for federal development of an irrigation system on lands that remained part of the reservation and included other considerations.

Disagreement about whether the Indians received fair compensation for their lands continues today, but a large portion of the reservation became available to non-Indian settlers under the provisions of the homestead and townsite laws of the United States.

Irrigation, the C&NW Railroad and new towns

The actual opening of the former reservation lands took place in 1906. With this formality came an extension of the Chicago and North Western Railroad from Casper to Lander; the establishment of the towns of Shoshoni (in 1905), and Riverton and Hudson (in 1906) along the route; and one of the largest irrigation projects in Wyoming.

The irrigation project was to be constructed by the Wyoming Central Irrigation Company, which was owned by Chicago salt magnate Joy Morton. Morton planned to use the money from water fees paid by settlers to build the irrigation system. But settlers wanted to wait to pay any money until the WCIC system was capable of delivering water.

Years of legal battles followed. Most of the original homesteaders gave up and moved on. More than a decade later, the U.S. Reclamation Service stepped in and assumed responsibility for the project, and only then was any real progress made. Irrigated farming became an economic mainstay of the county and soon, homesteaders arrived from throughout the country.

Coal, oil and railroad ties

The construction of the Chicago and North Western Railroad brought other developments as well. Coal was mined in small quantities for many years near present-day Hudson. With a railroad to buy significant quantities of coal, several large mining operations began. The opportunity for employment in those mines attracted many immigrants from southeastern Europe. By 1922, however, the railroad was converting its coal-fired locomotives to oil and within a short time the Hudson coal mines lost their biggest source of revenue.

Oil seeps had been known in the Lander area since the fur-trade era of the early 1800s, and the first oil well in Wyoming territory was drilled near the Little Popo Agie southeast of Lander in 1884. The arrival of the railroad finally made it possible to transport that oil to distant markets and justified exploration for additional oil fields across the county.

The railroad needed ties for the tracks throughout the C&NW system, and the timber for such ties was available in the Dubois area. The Wyoming Tie & Timber Company came into existence to produce those ties. The tie industry had a significant economic impact in both the Dubois and Riverton areas. Large numbers of Scandinavians came to Fremont County to work as tie hacks.

Uranium boom and bust

The first use of atomic weapons ended World War II in 1945, but within a short time the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in a race to develop more and more powerful nuclear weapons. Those weapons created a demand for uranium, and prospectors fanned out across the western states to meet the demand.

In Wyoming, J. David Love, an employee of the United States Geological Survey, made the first major uranium discovery in 1951 at Pumpkin Buttes in Campbell County. But the uranium bug hit Fremont County, too, and in September of 1953 a momentous find was made in the desolate Gas Hills of eastern Fremont County, about 45 miles east of Riverton.

Neil McNeice, a Riverton machine shop operator, and his wife Maxine, a school nurse, hunted antelope in the Gas Hills. On this particular trip, they brought a geiger counter that Maxine gave Neil as a Christmas present. They had been studying government-issued publications about uranium geology and while they searched for antelope they also looked for indications of uranium mineralization.

They saw something interesting on a Saturday afternoon and checked it with the geiger counter. What they found led to the discovery of a claim that eventually became one of the richest mines in the state. That mine became known as the "Lucky Mc" mine.

With their partner Lowell Morfeld and his wife Mary, the McNeices began staking a series of claims. They recorded those claims at the Fremont County courthouse in Lander, and word spread quickly. Prospectors from near and far descended on the Gas Hills to get a piece of the action. As production of uranium oxide began, the impacts were felt in both Lander and Riverton--especially Riverton.

What had been a town of about 2,000 residents supported primarily by area farmers soon became inundated with khaki-clad geologists, mining engineers and heavy equipment salesmen. The coffee shop in Riverton's Teton Hotel was filled with men trading information, lies and hot rumors of uranium activity. A stock exchange handling shares in local uranium companies operated on the hotel's mezzanine. Many Riverton residents drove the 40 miles to the Gas Hills daily to operate ore-mining machinery and mills that converted the ore into uranium oxide, or yellowcake.

Up on the Sweetwater River, where only a handful of cattle ranchers had lived, uranium discoveries led to the birth of the town of Jeffrey City, which quickly swelled into a community of 4,000 people.

The product of this new industry was used not only by the government for weapons but also by public utilities that began building nuclear power plants in the 1950s and ‘60s to meet the growing demand for electricity across the country.

But in March 1979, the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant south of Harrisburg, Pa., suffered the worst accident in commercial U. S. nuclear power plant history, when a partial meltdown of the core resulted in the release of small amounts of radioactive gases and contaminated water. Across the nation public attitudes about nuclear power changed. The market for yellowcake shrank. Through the early 1980s, mining companies laid off workers.

By the end of the 1980s, all of Fremont County's uranium mines had closed. Residents of Jeffrey City moved away to take jobs in other places and that town was virtually deserted and has not recovered. Riverton had become enough of a commercial center for west central Wyoming that it weathered the "bust" more effectively.

Iron ore

In 1962, meanwhile, U.S. Steel developed an iron-ore mine near Atlantic City. A mill at the mine site processed the ore and pelletized it for shipment by rail over a new railroad line south to Winton on the Union Pacific near Rock Springs, and from there to the company’s Geneva smelter in Provo, Utah. Most of the mine’s workers lived in Lander and commuted daily to the mine. But with the bottom falling out of the domestic steel industry, U.S. Steel closed the mine in 1983, and later the railroad line was removed.

Timber and natural gas

In the 1980s sawmills in both Dubois and Riverton closed, bringing an end to the county’s timber industry. The impact of that development was especially devastating to the Dubois community.

But at the same time drilling for natural gas in northeastern Fremont County began identifying huge new reserves. Technological improvements made it possible to drill to depths previously beyond reach. Soon the little-used roads surrounding Lost Cabin and Lysite were buzzing with activity and enormous drill rigs studded the skyline. But production has not reached its full potential in the early 2000s because a nationwide glut of natural gas has driven prices down to the point where production companies are limiting their development of additional resources.

A changing economy

As the county’s extractive industries declined in the late 20th century, county leaders promoted the development of tourism. But agriculture (including both livestock production and irrigated farming) remained dominant in the local economies.

The decline of extractive activity has also affected the Wind River Reservation. As revenue from their oil and gas properties has dwindled, the Shoshone and Arapaho tribes have turned to casino-style gambling for revenue. In doing so, the tribes have asserted their sovereignty and their unwillingness to be governed by state and federal statutes.

The tribes have also caused significant concern among non-Indian residents of the county by claiming some jurisdiction over non-tribal lands. The claim is based on the fact that much of Fremont County is completely surrounded by tribal lands and therefore should be considered as “Indian Country.” State, county and local governments have opposed those moves and many of the issues will undoubtedly be decided by the highest courts in the nation at a future date.

At the beginning of the 21st century Riverton has become Fremont County’s largest community with a population of well over 10,000 people in the city and the area immediately around it. Commercial activity in Riverton attracts people from all over the county and even from surrounding areas. Lander remains the county seat and boasts a population of more than 7,000. About 25,000 people live on the Wind River Reservation. The communities of Dubois, Hudson, Pavillion and Shoshone remain vital with their schools as the biggest unifying factors.

Resources

- Donahue, Jim, ed. “Administrative History of Fremont County.” Wyoming Blue Book, Guide to the County Archives of Wyoming, Vol. V, part I. Pp. 223-227. Cheyenne: Wyoming State Archives, 1991.

- Jost, Loren. Fremont County, Wyoming: a Pictorial History. Virginia Beach, Va.: Donning and Company Publishers, 1996.

For Further Reading

- See also the Wind River Mountaineer, published quarterly since 1985 by the Fremont County museum system. The magazine includes articles and photographs about the history of Fremont County and surrounding areas. Current and back issues are available in Fremont County libraries, or may be purchased at any of the three Fremont County museums. A complete index is in process but is not yet available. Subscriptions may be obtained by contacting the Wind River Mountaineer, 700 East Park Avenue, Riverton, Wyoming 82501.

Illustrations

- The photo of the Wind River a few miles below Dubois is by Craig Gaebel, from Panoramio. Used with thanks.

- The 1892 photo of Chief Washakie and dancers at Fort Washakie is from the National Archives, American Indian Select List number 73, via Treasurenet. Used with thanks.

- The rest of the photos are from the excellent collections at the Riverton Museum. Used with thanks.