- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Lucy Morrison Moore, “The Sheep Queen of Wyoming”

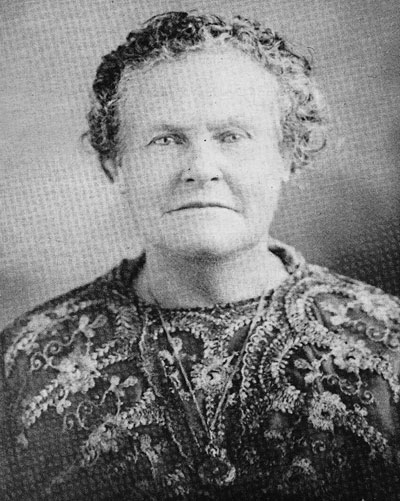

Lucy Morrison Moore, “The Sheep Queen of Wyoming”

Lucy L. Fellows was born Nov. 30, 1857 in California to parents who had come west in search of gold. The Fellows family with friend Luther Morrison soon moved to Sulphur Springs, Idaho, and in 1873, Luther, 44, married Lucy, 16. Over the next nine years, the couple had three daughters and built a herd of 3,000 sheep, but as Idaho became more populated, the Morrisons decided to move to the as yet unsettled region of Wyoming Territory’s Wind River valley. During their first winter, spent in the South Pass region near Atlantic City, they lost all but 200 of their sheep. Nevertheless, they followed through on their commitment, and eventually established a winter range northeast of present Shoshoni, Wyo., and summer range atop nearby Copper Mountain.

From 1882 to 1888, their nearest grocery store — and shipping point for wool — was 150 miles away in Rawlins, Wyo. Luther made the three-week round-trip twice a year while Lucy stayed behind to tend both children and sheep. (A son, Lincoln, was born in 1884.) For four years, the family lived in a tent banked with dirt and lighted with homemade mutton-tallow candles. Lucy did not see another adult white woman for five years. But their sheep, herded onto windswept ridges, survived the brutal winter of 1886-87 much more successfully than did cattle, and soon the Morrisons built a very profitable operation.

Luther died in 1898, but Lucy continued running sheep. During her peak years, her sheep grazed on many thousands of acres of public and private land, including additional winter range on Kirby Creek north of Thermopolis, Wyo. At one time, she employed herders to run 16 bands of sheep. As populations of sheep, cattle and people in the area increased after 1900, she gradually halved the size of her herd. In 1902, she married one of her herders, Curtis Moore. Unlike most of her employees, Moore was a parsimonious teetotaler, qualities that were more important to her than his social status. “I gave him a band of sheep for a wedding present,” she later said, “so I could marry a sheepman instead of a penniless sheepherder.”

Lucy, who had little desire for personal possessions, thrived on the nomadic life of a shepherd. After living just four years in a cabin, she lost that house to another squatter in 1890, but was happy to spend subsequent summers in a sheep wagon. (In 1891, the family built a winter home in Casper, Wyo., where the children could attend school.) However, Lucy was not a hermit. In 1900, she took her daughter Lovisa and her son, Lincoln, to Europe, and by 1916, when automobiles made travel easier, she would regularly drive from her sheep camp to church in Thermopolis.

Lucy believed that she was first called “The Sheep Queen of Wyoming” by men who envied her and wanted her range, but the term later became one of admiration. Lucy’s success probably came primarily from her passion for the sheep business: She was the sort of person who regularly turned conversations away from other topics to sheep. Her fame grew in part because of her success as a woman in a male-dominated field, and in part because wandering sheepherders enjoyed telling stories about her—many of them exaggerated. Author Caroline Lockhart used Lucy as inspiration for her 1919 novel “The Fighting Shepherdess,” although Lucy, who wanted to write her own memoir, insisted that Lockhart stick to the legends rather than using Lucy’s own history.

Lucy and her family were major figures in the battles between cattle ranchers and sheep ranchers in the 1890s and 1900s. The sheep business boomed between 1897 and 1910 and sheep production became Wyoming’s leading industry by the end of that time. But because there was still essentially no leasing system on the public range, and deep animosity between cattle and sheep grazers, conflict was inevitable. Between 1897 and 1909, there were hundreds of incidents, and a total of fifteen men, one boy, and about 10,000 sheep were killed in these conflicts. The worst of them was the Spring Creek Raid in 1909, when three sheepmen were murdered on a tributary of the Nowood River south of Ten Sleep, Wyo.

Many cattlemen, believing that sheep (rather than overgrazing by both sheep and cattle) were causing land to deteriorate, often drew “deadlines” across the public range. The deadlines, named for the seriousness of the threat they represented, unofficially banned sheep from one side of the line. In 1904, one deadline near Kirby Creek passed between Lucy’s winter and summer range, but Lucy refused to be intimidated by its threat.

On May 30, 1904, Lucy’s 21-year-old son, Lincoln Morrison, was ambushed and shot in a sheep wagon near Kirby Creek. The bullet missed vital organs, and Lincoln survived. Lucy offered a $3,500 reward, but the shooter was never apprehended. She wrote to Governor Fenimore Chatterton, “I dare not call on Bighorn County for protection for I know as soon as I do I will be found dead as was Minnick.” (Ben Minnick was a Thermopolis-area sheepman who had been murdered in a deadline dispute the previous year.)

During the 1910s, oil exploration became common across Wyoming. Lucy resisted, claiming derricks would desecrate her beloved pastures. When she finally relented, she did so partly because of her patriotic support of World War I and its rising demand for fuel, and partly because she earned a $10,000 advance for the oil rights. She invested the money in Los Angeles real estate. Through the 1920s, as Lincoln and his wife began playing a larger role in the sheep business, Lucy wintered in southern California.

Lucy suffered a severe stroke in 1930 and died in October 1932 in Casper. Curtis liquidated the sheep operation and moved full‑time to Los Angeles. It was the end not only of her life but of an entire era: After the federal government reformed the open range with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 and lowered protective tariffs, large-scale public-land sheep ranching slowly faded into Wyoming’s frontier history.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Moore, L.L. Letters to Governor Fenimore Chatterton, 1904, RG 0001.16, Box 2 File G–N, Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo. Moore writes of threats made by cattlemen.

- Morrison, Nell R. “Shepherds of Wyoming,” in Bob Edgar and Jack Turnell, Lady of a Legend. Cody, Wyo.: Stockade Publishing, 1979. This memoir by Moore’s daughter-in-law is the principal source for this article.

- Moore frequently appeared in newspaper stories -- especially after the 1904 shooting of her son Lincoln Morrison. You can search their names at the Wyoming Newspaper Project.

Secondary Sources

- Clayton, John. The Cowboy Girl: The Life of Caroline Lockhart. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 110-122. Discusses Moore’s interactions with Lockhart.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, pp. 179-182, 369-372, 374-377, 380-385.

- Davis, John W. A Vast Amount of Trouble: A History of the Spring Creek Raid. Niwot, Colo.: University Press of Colorado, 1993, 9-19.

Further Reading

- Shallenberger, Percy H. Letters from Lost Cabin. Casper, Wyo.,: Doug Cooper, 2005. Shallenberger’s letters to his business partner Tom Cooper in Casper, during the first years of the 20th century give a vivid picture of the uncertainties of running sheep on the public range.

Illustrations

- The photo of Lucy Morrison Moore is from Edgar and Turnell, Lady of a Legend, p. 66. Used by permssion, with thanks.

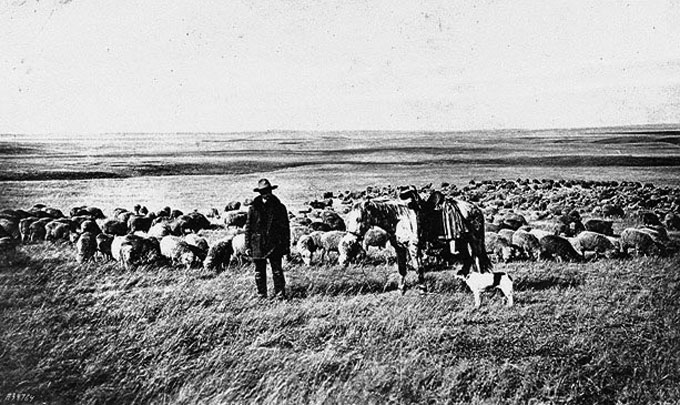

- The photo of the sheepherder and his flock is from Wyoming Tales and Trails, with thanks.