- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Establishing Public TV In Wyoming

Establishing Public TV in Wyoming

Building a public television network is usually a straightforward affair. You raise money, erect transmission towers, build a broadcasting studio and flip a switch. It's a formula that works. But building a PBS network in Wyoming was a lot harder. There were problems not faced by most of its sister networks—grizzly bears, for instance.

Wyoming public television engineers had to carry firearms and bear spray when they worked on transmission facilities in bear country. And if it wasn't bears, it was winter weather. PBS crews fought subzero mountain temperatures, high winds, and snow drifts tall as a two-story building.

Even with all that, the biggest issue was money—never enough to complete a transmission network across a state as unpopulated and vast as Wyoming. More than three decades after public television hit Wyoming airwaves, nearly one in seven residents still doesn’t get the network over the air, or through cable or satellite.

Yet by most measures, Wyoming PBS, as it became known in 2008, has been a success. The network scraped up the cash to build more than three dozen transmission sites despite an extended oil bust that impoverished the state in the network's early years. Once up and running, the network watched nickels and dimes so it could afford to produce its own programs about the state's government, economy, people and history. And Wyoming PBS somehow found a way to reach six of every seven residents over the air, or through cable or satellite. It reaches many of the rest through the Internet, cell and mobile devices.

The search for stable funding

Turn on Wyoming PBS and you'll see the same syndicated programming that you will find on PBS affiliates in other states that have far more money. It runs multi-part dramas, a one-hour nightly newscast, and investigative segments on everything from football head injuries to the causes of the Great Recession. You can learn Scandinavian, Mexican or Italian cooking. You can find out how to build a house or fix one up. And you can learn about Wyoming’s former U.S. senator, Al Simpson, or about the deadly blizzard of 1949, which paralyzed much of the state.

Today, Wyoming's PBS affiliate pays for all of this largely through public funding. The state owns the station and contributed 60 percent of its 2015 budget. The federal government contributed 31 percent. The rest came from viewer donations, corporate sponsors, sale of DVDs, and earnings on a small endowment.

These income streams can shrink or swell with the economy and with decisions by elected officials on where to allocate tax dollars. For instance, the federal government has done away with grants for new equipment. By contrast, the state has been particularly helpful in recent years. It funded the shift from analog to digital signals that enables PBS to broadcast in crystal-clear high definition. It also provided $1.5 million for an endowment and paid for a $1.5 million mobile production studio.

This feast-or-famine existence has driven Wyoming PBS officials to spend carefully and worry a lot about money. "The No. 1 issue for most stations is stable funding, and that's the issue for us," says Ruby Calvert, the network's retired general manager. "At least 30 percent of our time is spent raising money."

Lately, there has been more reason to worry. During the recent energy boom, oil prices topped $100 a barrel and state coffers overflowed. But in the current bust, prices tumbled below $30 a barrel before recovering somewhat, and the state's two-year budget projections call for a $600 million shortfall. PBS officials in 2016 are planning for possible cuts in state aid.

Cast-offs and hand-me-downs

When state government moved to create a PBS affiliate in the early 1980s, the new station had just over $1 million from federal and state funding along with $200,000 and studio space donated by Central Wyoming College in Riverton. Casper's K2TV donated an old transmission tower after it built a new one. The money and the tower enabled the new station to reach Fremont County, where Riverton is located.

But the remaining 22 counties had no service. There was little money to pay for the enormous transmission network that statewide service would entail. So at the outset, the new network made do with additional hand-me-downs.

"Our early system was built in part with cast-off equipment donated by commercial television operations," says Bob Connelly, a telecommunications engineer and the network's retired assistant general manager. "It was stuff they didn't need because they were upgrading to more modern gear. But it was free. If it hadn't been donated, some communities would have gone unserved."

The network also needed to find places for the dozens of transmission facilities required to cover the state. Those decisions were dictated by topography. "If you ever see a bunch of television engineers running around, they're always looking for the high ground," says Connelly.

"The higher the antenna, the more coverage area you'll get. When I first started, I was back East. They don't have a lot of high locations, so they have high towers—2,000-foot towers are not uncommon. Out here, we have the mountains. Our towers are only 200 feet (or less), but they're set on mountains thousands of feet over the people who watch us."

Most viewers lived on the plains, and network engineers had to figure out which mountaintop locations would reach the widest areas. But these locations also needed some sort of access roads. They also needed a power supply to run transmission facilities. One by one, the station's engineers identified the best candidates, and over time the network grew to include 38 sites—three for main transmitters and 35 others equipped to relay signals to nooks and crannies around Wyoming.

Many other PBS stations don't have these problems. For instance, WNET in New York City serves more than 20 million people who are crammed into less than 7,000 square miles. "WNET is able to reach a potential audience of tens of millions of people with two transmitters," says Terry Dugas, general manager of Wyoming PBS. One of these is atop the Empire State Building, which rises 1,454 feet from the street to the top of its broadcast antenna. If WNET engineers need to work on the transmitter, they take the elevator.

By contrast, Wyoming's 580,000 or so people are scattered across about 98,000 square miles, making it the least populated but 10th largest state by area.

Maintenance in a harsh climate

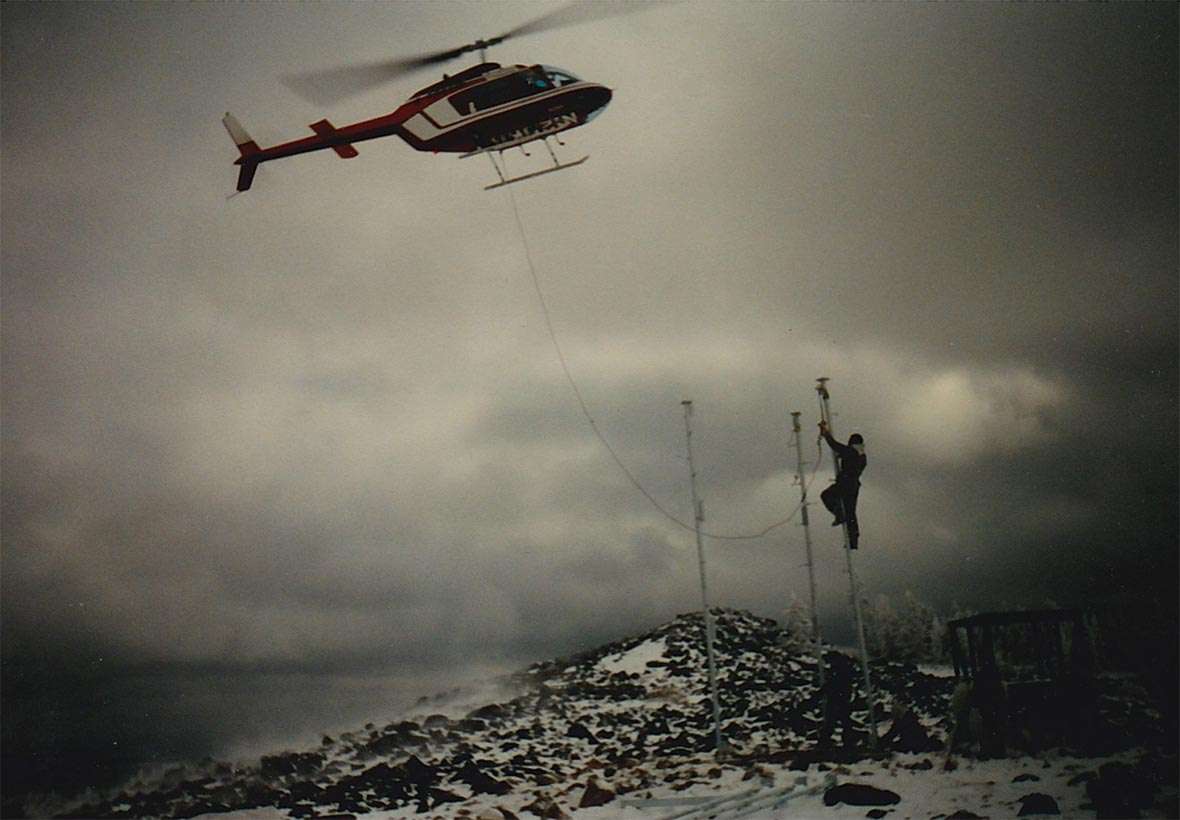

And thanks to Wyoming’s rugged terrain and harsh climate, equipment repair can look like an extreme sport. In frigid winter weather, climbing a television tower that sits 8,000 feet above sea level--and then staying up there for hours--drains the body.

"I've climbed a lot of towers in my day," says Connelly. "Your muscles tighten up. Sometimes you say, 'I have to get down. If I don't get down while I still have some feeling and muscle control, I'm not sure if I'm going to be able to get down.' But if you go down and warm up, then you just have to climb back up."

Sometimes mountaintop repairs require extended stays because of the complexity of the job or because the weather suddenly deteriorates to the point where the engineers are simply stuck. For that reason, they work from a vintage Sno-Cat, a vehicle that offers warm shelter and holds enough food to allow survival for days. With its tank-like treads, the Sno-Cat also offers a superior form of transportation up and down snow-covered peaks. The state paid for the vehicle back in the 1980s and PBS has made it last.

In the very worst weather, repairs have to wait. "There were times when 15 minutes on the tower was too long," says Connelly. "On more than one occasion we turned back. Meanwhile, people go without public TV. The phone rings off the hook and people are upset. I would tell them, 'I know you're upset. But it's too dangerous to send somebody up right now.'"

Summer is less problematical, though not without risks. In certain areas, bear spray and firearms are standard equipment. Though there have been no clashes between engineers and bears to date, on one occasion Connelly saw grizzly bears feeding below the Lava Mountain site where his crew was working.

Still, there are redeeming features of working at heights that can exceed 10,000 feet. "When the weather is nice, it's absolutely gorgeous," says Connelly. "It's a good thing there are days like that, because there are others when there's not enough money to pay you for doing the job."

Changing technology

Since the early days of Wyoming public television, technology has offered more ways to reach more viewers. They can now access the network over the air, by cable or satellite, through the Internet, and on cell phones or other mobile devices.

But technology has also cost Wyoming PBS a chunk of its potential audience because satellite television networks, which have grown in popularity, aren't required to carry Wyoming PBS when they broadcast to the state. Residents in only five of the state's 23 counties can get Wyoming PBS through their satellite provider. The other 18 counties get signals from out-of-state PBS stations based in Denver, Salt Lake City, or Rapid City, S.D. That cuts Wyoming PBS off from satellite subscribers in Cheyenne and Laramie, among other places.

This is especially costly to Wyoming PBS when it tries to raise funds from viewers to cover the cost of serving the state and producing Wyoming news and feature stories. "They don't give to Wyoming PBS if they're picking up Denver, Salt Lake, or Rapid City," says Ruby Calvert, the station's retired general manager. "They're going to give to whatever PBS station they're watching."

Still, Wyoming PBS has fared well in one critical measure—maintaining viewership. In May 2010, some 31,500 Wyoming residents watched PBS at least once a week. By May 2016, viewership had climbed to 32,600. In the same time period the major over-the-air networks suffered substantial losses to cable and satellite channels and to online streaming. "Wyoming PBS's consistent viewership comes from the unique programming we offer," says general manager Dugas.

The early years

Congress created PBS through the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act, which led to the creation of the federally funded Corporation for Public Broadcasting and a network of member stations around the country. The first public television station began broadcasting in 1970. Wyoming did not follow until 1983--the 49th state to do so. Only Montana took longer to get a station going.

The idea for a PBS affiliate in Wyoming had been kicked around for years. Planning began in earnest in the early 1980s. Central Wyoming College agreed to host the new station and help pay for it. But as the 1983 startup date approached, things began to unravel. Two of the linchpins of Fremont County's economy—an iron mine and a uranium mine—closed in short order, leaving thousands of workers jobless. Many of them abandoned homes they couldn't pay for. Soon housing prices collapsed and so did county property-tax revenues, which helped support the college. The college gave Wyoming Public Television $200,000 in 1983. "After that, money from the college dried up completely," recalls former general manager Calvert. "That was something we hadn't counted on. They withdrew all support except letting us stay in the studio space." It was an early warning of the station’s roller coaster existence.

Despite the setbacks, the station pushed ahead with plans to open. By early spring 1983, everything was in place. Engineers went to the top of Limestone Mountain in the Wind River Range north of Atlantic City, Wyo. and ran tests, communicating by walkie-talkie (there were no cell phones back then), to make sure signals were coming through back in Riverton. Everything worked.

May 10 was launch day. At precisely 4 p.m., station administrators flipped a switch and looked at a television set that was already tuned to their station. The station's logo appeared. Then the logo disappeared and Big Bird popped onto the screen. For the first time, Wyoming residents could watch Sesame Street on their own station. The staff and a crowd of onlookers broke into cheering. Public television in Wyoming was finally up and running.

Resources

Primary sources

- Calvert, Ruby, retired Wyoming PBS general manager. Telephone interview, February 16, 2016.

- Connelly, Bob, Wyoming PBS assistant general manager. Telephone interview, February 10, 2016.

- Dugas, Terry, Wyoming PBS general manager. Telephone interview, February 23, 2016

Secondary sources

- PBS. “About PBS.” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.pbs.org/about/about-pbs/.

- PBS. “Overview.” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.pbs.org/about/about-pbs/overview/.

- Wyoming PBS. “About Wyoming PBS.” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.wyomingpbs.org/about.php.

- Wyoming PBS. “Wyoming PBS Foundation.” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.wyomingpbs.org/foundation.php.

- Wyoming PBS. “Why Underwrite on Wyoming PBS?” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.wyomingpbs.org/underwriting.php.

- WNET, New York Public Media. “Media with Impact.” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.wnet.org/.

For further reading and research

- Roberts, Phil. "The Quest for Public Television." Annals of Wyoming, 70:3 (Spring 1998), pp. 34-43. Accessed Sept. 13, 2016 at https://archive.org/stream/annalsofwyom70141998wyom#page/n139/mode/2up.

Illustrations

- All photos are courtesy of Wyoming PBS. Used with permission. Special thanks to Assistant General Manager Bob Connelly.