- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Sublette County, Wyoming

Sublette County, Wyoming

Sublette County, Wyoming’s sixth largest, is located in the western part of the state and covers approximately 3.2 million acres, 80 percent of which are public land. The Wind River Range runs north to south along the eastern portion of the county, the Gros Ventre Wilderness lies to the north, and the Salt River and Wyoming ranges run along the western side. The central portion of the county is a valley comprised largely of sagebrush. Elevation ranges from 6,280 feet in the valley to 13,400 feet in the Wind River Range. The county hosts more than 1,300 lakes. The mountain ranges give birth to numerous fast-flowing streams that find their way into the Green River. Isolated geographically, first from railroads and then from interstate highways and population centers, the county retained its frontier culture far longer than many areas of Wyoming and the West, and its population remained sparse until well into the 20th century.

Early History

Three well-known archeological sites place indigenous peoples for thousands of years in what’s now Sublette County. The Wardell Buffalo Trap is the oldest known kill site where hunters used bows and arrows, and dates back approximately 1,000 years. The Trapper’s Point Antelope Kill Site has been radiocarbon‑dated to 7,880 to 4,690 years ago. And archeologists excavating the J. David Love Site in the Jonah Field south of present Pinedale uncovered the oldest burial in Wyoming, dating back 7,200 years. Archeological data suggests that people have lived here for at least 9,000 years. Archeologists also believe all of the natives were seasonal, moving out during the winter and returning for the summer.

For a few hundred years prior to the arrival of whites in the 1800s, the valley was summer home to Shoshone Indians, as documented by Wilson Price Hunt in 1811. The area was also a crossroads for other tribes. Crow certainly visited the valley, as noted by Robert Stuart in 1812. Possibly Blackfeet, Arapaho, Ute and Bannock also visited the area.

Mountain Men and the Rendezvous

The first Euro-Americans to arrive in the Rocky Mountain region came for beaver in the mountain streams and rivers. Beaver pelts were relatively small and easy to transport and brought good prices in the eastern markets. Beaver fur hats were the fashion in the United States and Europe, increasing demand. What is now Sublette County lies in the heart of what was some of the most productive beaver country in the Rocky Mountain West. The Green River and many of the streams in Sublette County were heavily trapped by the mountain men.

Trappers were known to be in Wyoming as early 1807 when John Colter came to the country, but historians consider 1820 to 1840 the peak years of the beaver fur trade. In the East and Midwest, Indian and white trappers alike had long brought furs to trading posts. But opposition to the trade in the early 1820s from Indians along the Missouri River hindered the transactions. William Ashley of St. Louis adapted a Canadian trading system about this time that would be known as the rendezvous. Ashley put the word out to trappers to meet the following summer at a chosen site in the midst of the best trapping grounds to trade the season’s catch.

In the following decade, six annual trappers’ rendezvous were held near the junction of Horse Creek and the Green River near present-day Daniel, Wyo., in 1833, 1835, 1836, 1837, 1839 and 1840. Here the season’s take in pelts was traded for powder and ball, Green River skinning knives, traps, blankets, trade beads and whiskey.

But just at the time trapping killed off most of the beaver, silk hats replaced beaver ones. The beaver boom disappeared. The 1840 rendezvous was the last one.

The Great Westward Migration and the Lander Wagon Road

Starting in the early 1840s, a trickle at first and later a flood of people began making the 2,000- mile trek from the Midwest to Oregon, California, and the 1,000-mile trek to Utah. As many as half a million people crossed what’s now Wyoming bound for these places before the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869.

In what’s now Wyoming, the emigrants crossed South Pass, the only wagon route through the Rocky Mountains. Many former mountain men with knowledge of western terrain became scouts and trail leaders for the emigrants. Once over South Pass, they followed the Mormon Trail to Utah and Salt Lake City or chose any of a number of routes and cutoffs to California or Oregon.

First of these was Sublette’s Cutoff, probably blazed by William Sublette in 1826 as a shortcut between South Pass and the Bear River. This cutoff is located just south of the modern-day Sweetwater-Sublette County line.

Second was the Lander Cutoff or Lander Wagon Road. This shortcut between South Pass and the Snake River region crosses what’s now the southern end of Sublette County. It was built late in the history of the Oregon Trail and was the only portion of the trail constructed with government funds and expertise. The route took travelers north of present Big Piney, Wyo., up South Piney Creek through Snyder Basin and Star Valley, and into what is now Idaho, past Gray’s Lake to Fort Hall near present-day Pocatello, Idaho. This road was named in honor of Frederick W. Lander, an engineer with the U.S. Department of the Interior, who surveyed the path and supervised its 1857-1859 construction.

Sublette County’s First Settlers: Cattlemen

Emigrant journals described the areas as “inhospitable and uninviting” with alkali-tainted water that killed their stock. It was yet another treeless expanse on the travelers’ long journey, home to Indians believed—often incorrectly—to be hostile, and there seemed little reason to stay.

The area was not conducive for farming, but in the late 1870s, cattlemen recognized its grazing potential. A surplus of cattle in other regions combined with the completion of the transcontinental railroad to help make the cattle business possible in Wyoming. Cattle were turned out and fattened on Wyoming grass and shipped by rail to eastern markets. Cattlemen discovered that, like the native buffalo, their stock could graze year-round on sparse but nutritious prairie grasses that cured on the stem in the dry climate.

Ranchers settled along the major watercourses, and at first had only limited competition for the surrounding grazing lands. They raised primarily beef cattle, but often maintained sheep and a few dairy herds. Some of the original beef herds were stocked with Mormon cattle from the Salt Lake Valley and outlying Mormon settlements. Many herds were also driven back over the Lander Road from Oregon, and from Texas via eastern Wyoming and Colorado.

The blizzard of 1889-1890—two years after the winter that killed so much stock in eastern Wyoming and Montana—wiped out many cattle herds in the Green River Valley on ranges already heavily overstocked. Ranchers gradually stopped depending on winter grazing for their cattle, cleared sagebrush in low areas and developed irrigation systems to grow natural hay for winter feed.

In the late 19th century, cattle were shipped to market at three to four years of age. In the fall, cattle from Daniel, Big Piney and La Barge were trailed to Granger, on the Union Pacific Railroad near Rock Springs, a six-to‑seven day drive. From there, they were shipped by rail to Chicago and later Omaha, Neb. When the U.P.’s subsidiary, the Oregon Short Line, was later constructed from Granger to Pocatello, Idaho, the nearest Sublette County shipping point became Opal in present Lincoln County, a five-day trail drive from the Big Piney area.

Cattle drives from the Cora-Pinedale-Boulder area in the northeastern part of the county to shipping points farther east often took more than twice as long, from 10 to 20 days. These crossed the small Little Colorado Desert and much larger Red Desert to such points as Rock Springs, Wyo., and Wamsutter, Wyo. Many of the cattle from the upper Green River Valley were also driven to Opal.

Starting in the late 1920s and early 1930s, ranchers began using trucks to haul cattle, although trailing cattle to market continued in the county into the early 1940s.

Some of the earliest Sublette County cattle ranches still operate today with fifth or sixth generations running the businesses. Haying and feeding is mechanized, and cattle are shipped in semi trucks, but cowboys on horseback moving herds are still a common sight. This is particularly true on the Green River drift–the stock trail used since 1896 to move cattle from spring range in the southern end of the county to summer range on the U.S. Forest Service allotment in the upper Green River Valley and back again in the fall to the ranchers’ home places for winter.

Creation of the County

When Wyoming Territory was created in 1868, its Legislative Assembly established four large counties stretching north-south from border to border. The Green River country that would later become Sublette County was initially divided between Carter County and an unorganized strip of land along the territory’s western border. This strip subsequently became Uinta County, the borders shifted and Carter County’s name was changed to Sweetwater. In 1884, Fremont County was carved out of a portion of Sweetwater County. Citizens in the upper Green River country had to travel to the distant county seats of either Evanston (Uinta County) or Lander (Fremont County) or after 1911, when part of Uinta County became Lincoln County, to Kemmerer, its county seat.

Then in 1921, Wyoming Rep. P.W. Jenkins of Cora introduced House Bill 17 to create the county of Sublette. It included the portion of Fremont County on the west side of the Wind River Mountains and the eastern portion of Lincoln County, but not Kemmerer. Supporting Jenkins was Rep. Oscar Beck of Big Piney, representing Lincoln County. The Wyoming Legislature passed the bill in February 1921; it was signed by Governor Robert Carey and sent home with representatives Jenkins and Beck for local ratification. Jenkins named the bill in honor of fur trapper and trader William Sublette, one of three brothers active in the fur trade in early 19th century Wyoming.

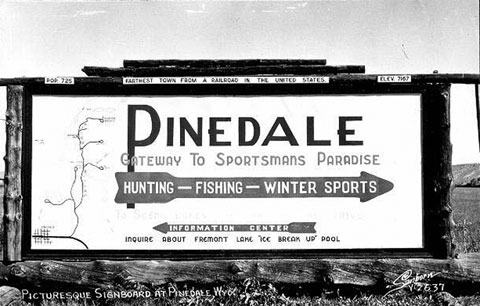

In a hotly contested local election in June 1921, Pinedale won the county seat designation by a mere six votes. Big Piney and Daniel were also on the ballot. The county numbers on Wyoming’s license plates are based on the assessed valuation of each county in 1928, when the numbers were first assigned. Sublette was designated 23–last in the state. Since 2000 and the recent natural-gas boom in the county, it has vied for number one in assessed valuation, taking turns with coal-rich Campbell County.

Tourism

Tourism has been an economic venture in Sublette County since territorial years. One of Wyoming’s first dude ranches was established by Billy Wells in 1887 in the upper Green River Valley. Paying guests–dudes—from the East or Europe came west for the mountain experience. Big game hunting in the fall was especially popular with guests who endured long, difficult trips to get there.

Other dude ranches included a hunting lodge built by B. F. Bondurant about 1904 in the northern end of what would become Sublette County. The Z Bar U and the Box R Ranch and others opened in the Hoback area northwest of Bondurant and in the upper Green River Valley. Visitors often needed references to be accepted as guests. Activities included riding, swimming, fishing, mountain climbing, dances and a rodeo. Pack trips into the mountains were also offered.

The Great Depression, better roads and the popularity of the automobile brought dude ranching’s decline. Tourism became big business in Wyoming after World War II, but dude ranching accounted for a much smaller portion of revenue. A few successful dude ranches still operate in Wyoming and Sublette County, but the industry never regained the popularity it enjoyed in the 1920s.

Area chambers of commerce have worked diligently since the 1930s to bring in tourists, and tourism remains important in Sublette County, particularly in the northern end, close to the mountains, lakes and streams.

Logging

A new industry–the production of railroad ties--was brought to the area when the transcontinental railroad was built across southern Wyoming in 1867-1868. Two important factors enabled this industry: large stands of lodgepole pines in the mountains and many “drivable” streams and rivers for floating ties to the Green River City, where the Union Pacific crossed the Green River. Ties were cut for the initial railroad construction, but eventually an enduring replacement industry developed and lasted into World War II.

Ties were hand-hewn by skilled “tie-hacks” from Sweden, Norway, Finland and Austria. The hewn ties were delivered to market by huge drives when the ties were floated down the Green River and its tributaries with help from the tie‑hacks. These “river rats” often rode the logs down the stream, and were paid well for their dangerous, backbreaking labor.

Centers of such activities included the Kendall tie camp on the upper Green River, organized in 1896, and big enough for its own post office by 1899. Supplying the tie camps with food and equipment brought more business to the area.

Operations spread southward in the 20th century to the North and South Cottonwood Creek drainages in the Wyoming Range northwest of Big Piney. The tie industry flourished on the Cottonwoods throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Timber work moved north from there to North and South Horse Creeks in the 1930s.

Ties were cut along both creeks and on Dry Beaver Creek near Daniel, where portable sawmills were in use by the late 1930s. Gradually, portable sawmills, chainsaws, tractors, road, and haul trucks replaced the broadax and tie drives. The era ended in 1940 when the Union Pacific stopped accepting hand-hewn, river-driven ties because they were too uneven and their quality inconsistent. Additionally, the railroad no longer wanted water-soaked timber as it was too hard to treat it effectively with preservative.

Oil and Gas

Oil was reported by emigrants in the 1840s who used it to grease their wagon wheels. Drilling for oil and natural gas in Sublette County, though, had a slow start. The first drilling took place in 1907 close to the future location of Calpet, near the southern border of the county in what became the La Barge Oil Field. One of the chief drawbacks to development was the field’s location--35 miles by wagon road from Opal, the nearest railhead. A road also reached the field from Kemmerer, but was poorly maintained. Neither one was worth much for transporting heavy drilling equipment. Early oil men, including W.D. Newlon—often called “the father of the La Barge Field,”—went broke through losses on these investments. Newlon’s rig burned before his first well was completed. Even so, he returned and drilled the first producing well in the area at Gobbler’s Knob in September 1923. Other successes soon followed, and Newlon formed several oil companies including the La Barge Oil Company and the Wyoming Oil Reserve Company.

The town of Tulsa, Wyo., was developed in the early 1920s—probably with hopes it would rival its Oklahoma namesake. Tulsa soon had a post office, a hotel, garage and grocery stores. La Barge, Wyo., was founded two miles west around the same time with town lots advertised at astronomical prices. But by 1928, the La Barge townsite was a ghost town, casualty of an economic downturn, and the remaining buildings were moved to Tulsa. In the 1930s, the name Tulsa was changed to La Barge to avoid mail confusion. It remains La Barge today, located just over the line into Lincoln County, but owes its existence to Sublette County oil fields. Decade after decade, La Barge continues to endure the booms and busts of the oil and gas industry.

In 1926, the California Petroleum Corporation bought out Beneficial Oil and most of Newlon’s interest and built the Calpet Camp in Sublette County about three miles west of present-day La Barge. Calpet grew quickly with a cookhouse, houses, recreation hall, machine shops and a school all constructed in short order. In 1927, the company built a small refinery, which furnished electric power for Calpet and gasoline for local use. Workers and their families stayed in Calpet until 1956 when the refinery closed.

A pipeline from La Barge to Opal brought a major improvement in transporting oil. In 1928, workers suffered through a tough winter, digging the line by hand with only shovels, for the Midwest Pipeline Company. The line began operation in January 1929, ending the previous era of trucking crude. Heater stations were maintained, and the line was patrolled daily. By that year, the La Barge Field boasted 80 to 100 wells producing 2,000 barrels of crude oil daily.

Exploration led to other discoveries nearby, including the Dry Piney Field eight miles to the northwest. By 1938, 20 wells had been drilled in that area, but only one small oil well and a gas well were producing.

The La Barge Field was gradually expanded northward when the Tiptop Unit was developed in 1948. In 1953, a four-inch, 11-mile pipeline was laid from Tiptop and Hogsback to the La Barge Field. By 1960, the Hogsback Unit was included in the field.

In the winter of 1938, the Wyoming Petroleum Corporation’s Budd No. 1 discovery well set off wild speculation when it blew. The derrick was coated in an estimated 700 tons of natural gas and ice before the workers succeeded in shutting in the well. The rig had been idle for three weeks at a depth of 1,695 feet when the hole unexpectedly blew in.

On Sept. 9, 1952, Western Oil Refining Company’s No. 2 well also blew out. It took ten days to finally case and seal that well. Eventually, the blowout location would lead to the discovery of the Big Piney Shallow Field, so called because its oil was close to the surface.

The Big Piney Gas Field, 15 miles long and up to three miles wide, runs north of the Dry Piney Field from a spot a mile and a half north of the North La Barge Field to a spot eight miles west of the town of Big Piney. Drilling activity in this field began in 1952 and was immediately successful with the ready-made market provided by the Pacific Northwest pipeline, running from the San Juan Basin in southern Colorado to the state of Washington.

Also in 1952, Arthur Belfer of New York City entered the picture in the Green River Basin. Belfer purchased mineral rights in the Big Piney area and began an intensive exploration and development drilling program with his company, Belfer Natural Gas. Belfer joined another company in the area, Belco Petroleum, and by 1955, the two companies controlled over 95 percent of the gas-producing area, including 33 gas wells. A pipeline was built to Opal to tap the field in 1956.

By 1978, the Big Piney-La Barge complex, consisting of the Tiptop, Dry Piney, Hogsback, La Barge and Big Piney Oil and Gas Fields, had produced an estimated 22 million barrels of oil and 537 million cubic feet of gas. While significant for the time and area, the amounts were dwarfed by production in the fields to the east in just a few decades.

Beginning in the early 1990s, new technology enabled the successful drilling of more natural gas in the southeastern section of Sublette County. The area known as (HYPERLINK: /essays/jonah-field-and-pinedale-anticline-natural-gas-success-story) the Jonah Field and the Pinedale Anticline was heralded by industry as one of the most significant onshore natural gas discoveries in the second half of the 20th century. In 2004, annual natural gas production in the Jonah Field was 247.3 million cubic feet and the Pinedale Anticline produced 136.3 million cubic feet.

In 2011, natural gas exploration and extraction continues to dominate the Sublette County economy. The industry continues to draw more federal and state employees to regulate it, more oilfield and gas field workers, and more people working for businesses that equip and supply the big companies. Many workers live in temporary camps on the gas fields. Yet the area is also a permanent home to full-time energy employees, largely the ones in management positions. Together, these people and their families have made Sublette County the fastest growing county in Wyoming. Its population swelled 73 percent from 2000 to 2010.

The agriculture community continues to thrive in Sublette County, mostly because of cattle ranching, although it is nowhere near the dominating economic force it once was. Tourism, another of the area’s oldest industries, also remains strong, with the county hosting visitors annually from around the world. While Sublette County is larger than Rhode Island, the population is still small—10,247 in the 2010 census. Perhaps due to the tiny size, various population groups seem to get along reasonably well.

Almost everyone living in Sublette County has an appreciation for its nationally recognized outdoor recreation opportunities. In 2011, Pinedale was listed by Outdoor Life magazine as the second best place in the country for sportsmen to live.

Resources

- Housley, Doris Marx, Betty Carpenter Pfaff and Wanda Sims Vasey, eds. A Tale of Two Towns—Tulsa and La Barge.1977, pp. 48-65.

- Noble, Ann Chambers. “The Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline: a Natural-Gas Success Story”, accessed 5/20/11 at /essays/jonah-field-and-pinedale-anticline-natural-gas-success-story.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, pp. 163, 221.

- McKinley, Barbara, “Almy to Madison (A Story of Oil and Gas),” Seeds-Ke-De- Reflection, Pinedale, Wyo.: Sublette County Artists’ Guild, 1985, pp. 239 – 250.

- Moulton, Candy. Roadside History of Wyoming. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2001, pp. 35-44.

- Noble, Ann Chambers. Pinedale, Wyoming: A Centennial History 1904 – 2004. Pinedale, Wyo.: Sublette County Historical Society, 2005, pp. 76-83.

- Rosenberg, Robert G. Wyoming’s Last Frontier: Sublette County, Wyoming, A Settlement History. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press, 1990, pp. 17 – 61, 121 – 153, 207 - 218.

- Sublette County Artists’ Guild. Tales of the Seeds-Ke-Dee. Denver: Big Mountain Press, 1963, pp. 85 – 103, 253 - 262.

Illustrations

- The aerial photo of the rendezvous grounds is from Pinedale Online.

- The photo of the 1896 cattle drive is from the Sommers family collection, the photo of the tie hacks is from the Thelma Budd Collection, courtesy of Bill and Carrie Budd and the photo of the ice-encased gas well is from the Bill Williams collection, courtesy of Jonita Sommers.

- The photos of Marbleton and of the Pinedale sign are from Wyoming Tales and Trails. All published with thanks.

Field Trip: Tour of Sublette County

It is easy to see several historic sites by taking a loop driving tour in the center of Sublette County. This tour starts in Pinedale, but one can begin anywhere on the loop.

A bronze plaque located on the northeast corner of Pine Street and Franklin Avenue gives a good, brief history on the founding of Pinedale. This town is home to the Museum of the Mountain Man, open seasonally and well worth the visit. Local and regional history information is also available at the local library.

Leaving Pinedale, travel south on U.S. Highway 191. In 12 miles, you’ll come to the small town of Boulder. This community has only a post office, gas station, convenience store and hotel, servicing travelers and ranchers. In the early 1900s, though, it rivaled the town of Newfork, a few miles farther along.

Located on the west side of the highway, the original town of Newfork is now a private residence. Many of the town’s original 1880s buildings, including a store, post office and most obviously, the Valhalla Dance Hall, named after the Norse heaven for warriors, are still standing, but not open to the public. For years in the early 20th century, this building hosted dances and political rallies. The town “closed” when diphtheria broke out and took the lives of some of the founding family. The Newfork post office moved to Boulder, which already boasted a mercantile store, big hotel, dance hall and blacksmith shop.

Continuing south 10 more miles brings you to the Lander Wagon Road crossing. Be sure to stop and read the historic marker. It’s also worth crossing the highway to visit two other Oregon Trail markers placed there decades before.

Continue on U.S. Highway 191 another mile to U.S. Highway 351. Take a right—to the west--and travel the length of this road through the Pinedale Anticline Project Area, one of America’s largest natural gas fields.

A mile north of Highway 351’s crossing of the Newfork River is the spot where the Lander Road also crossed. This spot was acquired by the Sublette County Historical Society in 2010, and may be ready for tourists—with historic markers and a parking lot—as soon as by the summer of 2012.

At its western end, Highway 351 tees into U.S. Highway 189. At the junction, another marker for the Lander Wagon Road explains the area’s rich cattle-raising history. Get a little ways off “the loop” and travel south a couple of miles on U.S. Highway 189 to Marbleton and Big Piney.

Big Piney was incorporated July 5, 1913. The town was called "Ice Box of the Nation" when it was made a national weather station in 1930, as it had the coldest year-round average temperature of any place then known in the 48-state United States. (Since then, Alaska became a state, additional stations have been added, and Big Piney is no longer in the running for the United States’ coldest spot.) It is also home to the Green River Valley Museum, which offers excellent displays of local history.

Marbleton was incorporated in 1914. All attempts to combine the two have been unsuccessful.

Continuing back to the loop, travel north on U.S. Highway 189. A mile before reaching the town of Daniel, a historical marker explains La Prairie de la Messe, when Father Pierre De Smet conducted the first Roman Catholic mass in Wyoming on July 5, 1840, at the trapper rendezvous on Horse Creek. A monument at the Daniel cemetery marks the exact location. The three mile drive on a dirt road from the historical marker to the cemetery is well worth the visit. The view of Horse Creek in the valley below the monument is breathtaking.

One can also visit the rendezvous site on Prairie Creek north of Daniel in an area marked on the east side of the highway. The small town of Daniel contains only a post office and the Green River Bar and seems to have remained unchanged for decades.

One mile north of Daniel you return to U.S. Highway 191. Take a right, east, for the final stretch back to Pinedale. Five miles farther is U.S. Highway 352 to Cora on the left and County Road 110, or East Free River Road, on the right. Take a right--if the roads aren’t snow-covered--to Trappers’ Point, a well-marked lookout for the Green River Rendezvous location and the mountain ranges on the horizon. This is also the bottleneck of one of the world’s largest intact long-distance animal migrations. Tens of thousands of pronghorn use this route to migrate north and south seasonally. One group of around 400, the Teton pronghorn antelope, migrates from Sublette County all the way to Grand Teton National Park, making this the second longest recorded land animal migration in the Western Hemisphere after caribou in the arctic.

Six miles farther east, you’re back in Pinedale.