- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline: A Natur...

The Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline: A natural-gas success story

Throughout the 1990s, natural gas began flowing in steadily increasing quantities from two big fields southwest of Pinedale, in western Wyoming. The resulting boom has been hard on local wildlife and air quality, and has industrialized a local ranching and tourist economy, perhaps forever. At the same time, the production has brought millions in tax and royalty revenues to federal, state, and Sublette County coffers, and has brought millions of dollars in profits to the companies that developed the fields.

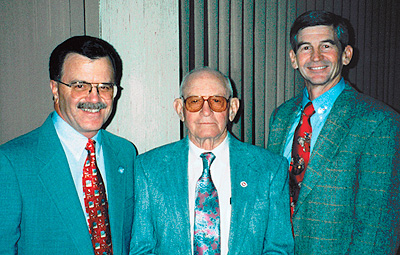

It all came about because a father, his son, and their partner in a little oil company in Casper, Wyoming, thought to try drilling the area another time, and the business sense to know when and how to go about it. The story goes to the heart of Wyoming’s oil and gas culture, and raises important questions about energy production’s long-term costs and benefits.

The Pinedale Anticline Project Area (PAPA) is located in central Sublette County, Wyoming, on a narrow, diagonal 30-mile swath of land that stretches from just outside the Pinedale town limits south along U.S. Highway 191 to about 70 miles north of Rock Springs. It consists of 197,345 acres, 80 percent surface of which is federal, operated by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), five percent is State of Wyoming, and 15 percent is owned privately. By 2000, the PAPA was one of the newest and most productive gas fields in the continental United States. Gas reserves are estimated at up to 40 trillion cubic feet. That’s enough to serve the nation’s entire natural gas demand for 22 months.

The Jonah Field is located south of the Pinedale Anticline and also in Sublette County. It is approximately 35 miles south of Pinedale and about 70 miles north of Rock Springs. After being rediscovered in the early 1990s, Jonah Field was heralded as one of the most significant on-shore natural gas discoveries in the second half of the 20th century. The field has a productive area of 21,000 acres and is estimated to contain 10.5 trillion cubic feet (297 billion cubic meters) of natural gas. The National Petroleum Council, in its 2007 report “Facing the Hard Truths about Energy,” estimated total traditional natural gas resources in the Lower 48 States to be 764 trillion cubic feet. Ninety-eight percent of this field is managed by the Bureau of Land Management, with two state sections of one square mile each, and one private section of land.

Early attempts

California Oil Company, later named Chevron, first drilled on the Pinedale Anticline in 1939 using rotary tools, state-of-the-art drilling equipment at the time. Working only from the geological clues visible on the earth’s surface, these early oilmen had correctly figured out where to drill. But after drilling 10,000 feet into the earth, they found very little of what they were after — oil. They did, however, find plenty of natural gas. Unfortunately, there was no market for the gas and the company plugged and abandoned the site.

El Paso Gas Company purchased the well but with hopes to drill for gas. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the company drilled a total of seven wells in the area, all producing limited gas, making the venture an economic failure.

But El Paso made plans to return to the Pinedale Anticline in a big way in 1969, to experiment with detonating nuclear devices to assist with natural gas extraction. This attempt, Project Wagon Wheel, was designed to study the effectiveness of nuclear power to mine natural gas. El Paso geologists knew there was plenty of gas below the anticline, but it was locked tightly in sandstone rock formations that resisted conventional drilling methods. Radioactivity, according to a company report, was not expected to be a problem.

When the citizens of Sublette County learned of the planned nuclear detonation, several of them formed the Wagon Wheel Information Committee to learn more about the project. The group soon committed to educating people and stopping the project. Eventually they succeeded. Determined citizens prevented big industry and the federal government from detonating nuclear devices in their county.

Meridian Oil Company drilled next for gas on the Pinedale Anticline. But this company had similar problems. Its results were hampered by traditional drilling methods which did not work well in the Anticline’s tight sandstones. And there still was no good market for natural gas.

Meanwhile, new pollution-control laws were changing the business. The Clean Air Act of 1970 was amended in 1977 and again in 1990 to specify new strategies for cleaning up the air. Most of the nation’s electrical plants had been powered by coal, which emits high levels of ash, sulfur dioxide and mercury. The new strategies led companies to look for cleaner energy, including natural gas.

The Jonah Field

Recognizing the changing demand for energy the men at a small company in Casper, Wyoming, thought that natural gas would be a good investment. This was the McMurry Oil Company, started by W.M. “Neil” McMurry, with his son Neil “Mick” McMurry and John Martin as partners. With great foresight, they identified natural gas as a “clean fuel,” because, when burned, it emits nowhere near the toxins produced by a fuel like coal. (Since then, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has noted that greenhouse gas emissions from the production and transportation side of the natural gas industry are cause for concern). At the same time, the price of natural gas was low–and gas leases were therefore inexpensive.

“There were a lot of opportunities in [natural gas] and no one else believed in it,” recalls Mick. John and Mick looked for natural gas prospects “that we could believe in and afford,” says Mick. “We looked up in Canada, Nebraska, and Kansas — fortunately, none of those came together.” Then they found something right in Wyoming. It was called the Jonah Prospect, next to the Pinedale Anticline.

In 1991, McMurry Oil Company (MOC) purchased three wells in the Jonah Field from the Presidio Oil Company, which had shown unpromising early results. Along with the three wells the McMurrys purchased mineral leases on 25,000 acres of BLM land in the Jonah area.

Making the prospective investment more attractive to MOC was a new, efficient way to get natural gas out of Wyoming. The Kern River Pipeline was then under construction, with political support from Wyoming Governor Mike Sullivan and financial support from the state legislature. Built by the Williams Companies, Inc. and Tenneco Gas Company in a 50/50 joint venture, the 926-mile pipeline would extend from Opal, Wyoming, about forty miles south of the Jonah Field, to the San Joaquin Valley near Bakersfield, California. It was operational by February 1992 with a capacity of 700 million cubic feet per day.

The abandoned Jonah wells were located approximately ten miles from the old Meridian Pipeline, built years before to serve a few other unproductive wells on the Pinedale Anticline. They had never been hooked up. The Meridian line connected to the processing plant at Opal, and thus would connect to the new Kern River system.

Wardell Federal #1, the first of the three gas wells that would end up in the McMurrys’ hands was drilled in 1975 by Marvin Davis of Denver and his Davis Oil Company. That well produced too little gas to be economical. Ten years later, Canada’s Home Petroleum acquired Davis Oil and drilled two more wells a mile north of Davis’ well. Home’s first well, the Jonah #1-4, tested more than two million cubic feet of gas per day, but during the drilling process the formation was damaged, impairing gas flow. Home Petroleum drilled second well in 1987. That well fell victim to falling natural gas prices and was completed in only one formation. During the industry downturn of the late 1980s, Home Petroleum sold the wells and their leases to Presidio.

Fracking

Natural gas in the Jonah Field is “locked” in tight rock formations. To extract the gas, first the well is drilled, and then the formations must be broken down, creating channels for gas to flow. This is accomplished by fracturing (fracking) a formation, when fluid and/or compressed gas is forced at high pressure down the well fracturing the gas-bearing rocks, creating cracks and fissures. These fissures become conduits for gas to flow out of the formation and up the steel pipe set in the well. To keep the formation from closing back on the fissures and resealing the rock, solid material is mixed in the “frack fluid” to prop the channels open. The most commonly used “propant” is sand, or “frack sand.”

McMurry Oil Company recognized that the only way to successfully draw the gas through the well-bores was to develop new drilling and fracturing technology that would allow free flow of the gas through the formation. The company sought advice from the best consultants in the gas industry. Petroleum engineer James Shaw greatly assisted in developing a whole new system – and it worked.

It had been the hope of the McMurry Oil Company and its partners that the wells would produce one million cubic feet per day. To everyone’s great surprise and pleasure, the three wells produced two million. McMurry Oil Company reported its first production of gas in the Jonah Field to the Wyoming Oil and Gas Commission in September 1992.

The success of its first Jonah Field wells encouraged the company to keep drilling in the area. Over the next few years the company picked up additional BLM gas lease sales. To cover the additional costs of more drilling, the small company took on partners.

Next, McMurry Oil Company moved north to the Pinedale Anticline when it acquired an interest in partnership with Meridian Oil Company. The partnership’s first well, the New Fork Federal #11-8 was sunk to 11,587 feet. Unfortunately, it was “non-commercial,” or not economically viable. MOC moved back to the Jonah Field and did not return to the Pinedale Anticline until late 1995. In the meantime, Meridian sold its interest to Ultra Petroleum.

In 1996, drilling expanded significantly when Snyder and Amoco Corporation moved into the Jonah Field. They brought 3-D seismic survey equipment, instrumental in delineating the field’s key boundaries. The 3-D surveys allowed Amoco and Snyder to drill wells within 500 feet of faults and to know exactly where they were going in the formation. The new data helped pinpoint the areas of highest production. “That’s what made Jonah successful,” observes Mick McMurry.

More pipelines, more drilling, more wells

Initially hampering production, however, were limited pipelines, as well as a scarcity of compression facilities, which increase the pressure of gas in pipelines and enable the gas to flow properly. Four-inch pipelines were soon replaced with eight-inch surface pipeline. Then in 1996, a twelve-inch gas line was constructed with a capacity of 100 million cubic feet per day. The following year, a twenty-three-mile, sixteen-inch pipeline was added to connect Williams Field Services, Questar (after 2011, QEP in this area), Western Gas Resources, and FMC pipelines from the Jonah Field to processing facilities at Opal, Granger, and Black Fork, Wyoming. This line increased the daily transportation capacity to 175 million cubic feet.

On September 1, 1999, the Jonah Gas Gathering Company, a Wyoming partnership operated and partially owned by McMurry Oil Company, opened a new 50.5-mile, twenty-inch pipeline. The new line would transport the majority of the gas from the Jonah Field to Opal, where it connected with the Williams Field Services gas process facility. From Opal, the gas was marketed into three different pipelines: Kern River, Northwest, and Colorado Interstate Gas. Completion of the Jonah Gas Gathering pipeline increased gathering capacity on the Jonah Field from 175 to 320 million cubic feet per day.

The increased pipeline capacity enabled drilling in the Jonah Field and the Pinedale Anticline to grow at a remarkable pace. In December 1997, the BLM reported 58 wells in place. By December 1999, there were more than 150 wells in both fields. By July 2001, the well count reached 300.

This rapid expansion was permitted by the BLM. In April 1998, the agency formally allowed full-field development. The operators believed at this time they would need 497 wells to fully extract natural gas from the Jonah Field, though the report noted that between 300 and 350 wells was “most probably” the number.

By late 1998, it was clear both estimates were low. The companies began what’s called infill drilling — drilling new wells among producing wells in a developed field, to yield more gas faster. Infill drilling would nearly triple the number of well pads that had been considered adequate by operators and the BLM in 1998. By December 2000, the well count had jumped from 497 to 1,347. The total projected lifetime of the field had accordingly dropped to twenty-five years, half of the original estimate.

In June 2000, Alberta Energy Company bought McMurry Oil Company and became a major interest holder in the Jonah Field with a 35 percent interest. In 2002, Alberta Energy changed its name to EnCana, and become North America’s top independent natural gas producer.

In November 2001, McMurry Energy, created after the MOC sold its Jonah interest, sold its Pinedale Anticline holdings to Shell, formally known as the Royal Dutch/Shell Group’s Energy and Production Company. This was the international company’s first foray into Rocky Mountain natural gas in nearly two decades. Other major companies soon followed.

After 2000, drilling in the Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline continued, spurred by high natural gas prices. In March 2003, the BLM reported that operators had requested permission for an infill drilling program that would add up to 1,250 new wells to replace their earlier request for 850 new pads. Surface well spacing would decrease to sixteen acres, or forty pads per square mile. The BLM raised its estimate of surface disturbance for wells and associated infrastructure by more than 40 percent, from 2,927 acres to 4,225 acres.

The Casper Star-Tribune reported in August 2003 that a total of 3,100 wells might ultimately be drilled in the Jonah Field — 1,300 more than had been requested in the March 2003 infill proposal. The recession in 2008 brought a drop in natural gas prices, resulting in a sudden reduction in drilling in the Jonah Field and the Pinedale Anticline. Drilling and production never stopped, but as of early 2011 was continuing at a slower pace. Drilling is likely to pick up again when the price of natural gas returns to a more profitable level.

Impacts

The Jonah Field rediscovery and successful extraction of natural gas initiated by McMurry Oil Company is heralded as one of the most significant natural gas developments in continental North America in the second half of the twentieth century. Jonah represents a turning point because of the enormous amount of production opened up by the new technologies. McMurry Oil Company’s technical advances in the early 1990s, coupled with higher gas prices and a quick boom in pipeline capacity, allowed it and other companies to lucratively produce gas from a previously inaccessible source. This success led to McMurry Oil Company’s expansion of the nearby Pinedale Anticline field a few years later.

Impacts brought on from drilling in the Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline were not always welcomed, however, in the small Wyoming communities surrounding the area, notably Boulder, Pinedale, Big Piney, Marbleton, and La Barge, and the bigger towns of Rock Springs and Green River. The boom strained community housing, schools, and such services as law enforcement and health care.

A 2005 study of Pinedale residents conducted by sociologists from the University of Wyoming found that the newcomers brought many new “social impacts,” and that longtime residents found it “increasingly commonplace not to recognize someone while going to the bank or buying groceries.” Services were harder to get. A quick stop in the store was no longer quick, with long lines at the checkout. It took a longer wait to see a local doctor. For the first time, it was hard to find a parking spot. Perhaps most noticeable was how difficult it became to cross Pine Street, Highway 191, Pinedale’s main drag, with the constant traffic of heavily loaded semi trucks.

Concerns were raised, too, about the industry’s impact on wildlife, particularly sage grouse, pygmy rabbits, pronghorn antelope, and mule deer. The Sublette mule deer herd, one of the biggest in the state, winters on the Mesa – the northern portion of the Pinedale Anticline. To protect the deer, the BLM restricted drilling during critical winter months until 2008, when a new plan was developed that allows for year-round drilling if the herd population can be maintained. Mule deer numbers have declined significantly, though. A 2010 BLM report shows a decline in 60 percent in deer populations from 2001 to 2009, based on annual estimates. The report blames energy development disturbance. On the Mesa, deer have also lost nearly 2,000 acres of habitat over the past decade, with the majority, 85 percent, of the habitat loss attributed to well pads and the rest to road construction.

Measures have been taken to try to reduce impacts to wildlife and the environment in the Pinedale Anticline. Gas companies are coordinating their drilling efforts into designated areas for year-round development. These Development Areas (DAs) allow the companies to concentrate their activities and timing in specified areas leaving large blocks of contiguous habitat undisturbed and available to big game and their migration corridors and sage grouse habitat. In an effort to reduce the amount of area disturbed, companies have been clustering their wells onto a single pad and then using directional drilling from the pad, resulting in fewer pads and roads needed for drilling activity. By 2010, this method had allowed 100 fewer needed well pads in the Pinedale Anticline Project Area and 70 percent fewer roads to fully develop the field, leading to less habitat disturbance.

Sublette County citizens are concerned about the increased water and air pollution connected with the development. Long-time residents noticed a decline in year-round air quality starting in 2000. Air pollution is now a way of life. The situation became dire in 2008 when the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality began issuing “Ozone Alerts.” Ground-level ozone results from chemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen and volatile organic compounds in the presence of sunlight. Ozone levels get too high when too many engines, from all sources, are pumping dangerous emissions into the atmosphere that are then “cooked” by the sun, often when there is a snow cover to intensify the sunlight. High ozone levels can be particularly dangerous to people with compromised immune systems and respiratory problems. Air quality monitoring is now required, with ongoing steps taking place to alleviate the potentially dangerous situation, though “Ozone Alerts” continue.

At the same time, positive impacts from the successful drilling in the Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline were immediate and far reaching. Millions of tax dollars have been collected as a result of the natural gas production in Sublette County, which have been used for improved infrastructure and community resources. Thousands of jobs have been created for local residents and for those willing to relocate to the area. Industry has also been very generous in volunteering time and donating money to organizations that serve the community. Industry operators have also worked with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to implement innovative technologies and operational practices that lessen the effect of natural gas operations on the environment.

Natural gas production continues in 2011, and so too, do many of the problems that came with it. Population growth has slowed somewhat since 2008, however, and the newcomers continue to be served reasonably well by private-sector housing and other services. At the same time, increased tax revenues have allowed local governments to be proactive in building infrastructure, and industry is working to alleviate the problems brought on by the drilling activity. Pipelines, for example, are being built to carry out the condensate now carried by large, dust-raising semi trucks. The BLM and Wyoming Game and Fish monitor the area, and face continued challenges.

Since 2010, additional natural gas fields in Wyoming and throughout the West have been located and development plans are underway. Citizens from Sublette County have been invited to these areas to discuss ways those communities can learn from Pinedale. These could be valuable lessons.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “Balancing Resources on the Pinedale Anticline.” The PAPA operators’ website, accessed Feb. 15, 2011 at http://www.papaoperators.com/.

- Ballou, Dawn. “Preserving Wildlife in the PAPA.” Pinedale Online! Jan. 18, 2010. Accessed Feb. 15, 2011 at http://www.pinedaleonline.com/news/2010/01/PreservingWildlifean1.htm.

- Ecosystem Research Group. “Sublette County Socioeconomic Impact Study, Phase II – Final Report.” September 28, 2009. Prepared for Sublette County Commissioners. Accessed Feb. 15, 2011 at http://www.sublettewyo.com/DocumentView.aspx?DID=392.

- Ostlind, Emilene. “Fox Guarding Pinedale Henhouse? Critics Call Wildlife Count ‘Unsound Science.’” WyoFile.com, July 12, 2010. Accessed Feb. 15, 2011 at http://wyofile.com/2010/07/fox-guarding-pinedale-henhouse-critics-call-wildlife-count-unsound-science/.

- “PAPA SEIS ROD Implementation.” Includes the Bureau of Land Management’s Record of Decision (ROD) for the Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) in the Pinedale Anticline Project Area (PAPA), with related links. Accessed Feb. 15, 2011 at http://www.blm.gov/wy/st/en/field_offices/Pinedale/anticline.html.

- Sawyer, Hall and Ryan Nielson. “Mule Deer Monitoring in the Pinedale Anticline Project Area: 2010 Annual Report.” Prepared for the Pinedale Anticline Planning Office of the BLM, Sept. 14, 2010. Accessed Feb. 15, 2011 at http://www.wy.blm.gov/jio-papo/papo/reports/2010annualreport_muledeer.pdf.

Secondary Sources

- Lederer, Adam. “Project Wagon Wheel: A Nuclear Plowshare for Wyoming,” Readings in Wyoming History: Issues in the History of the Equality State, fourth edition, edited by Phil Roberts. Laramie: Skyline Press, 2004, 214-227.

- Noble, Ann Chambers. Hurry McMurry: W.N. “Neil” McMurry, Wyoming Entrepreneur. (Casper, Wyo.: VLM Publishing LLC, 2010.) Includes more on the McMurry Oil Company and on fracking on the Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline.

- __________________. Pinedale, Wyoming: A Centennial History 1904 – 200. (Pinedale, Wyo.: Sublette County Historical Society, 20005.) Includes more on Project Wagon Wheel and the Wagon Wheel Information Committee.

Illustrations

- The photo of the Pinedale Anticline from the air, 2009 is courtesy of the field’s current operators: Ultra/Shell/QEP.

- The photos of the founders of the McMurry Oil Company, Halliburton pumping the frack on the company’s first wildcat well, and of the pipeline construction are all courtesy of MOC.

- The photo of the working drill rig on the Pinedale Anticline is by Jonathan Selkowitz, from SkyTruth, used by permission.