- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The North Platte River Basin: A Natural History

The North Platte River Basin: A Natural History

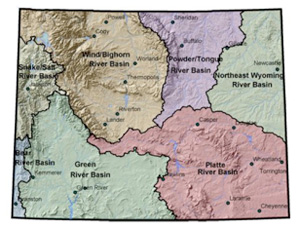

A map of Wyoming’s watersheds shows the North Platte River basin, in the southeast corner of the state, shaped like a balled fist with its index finger pointing west toward Utah, California and Oregon. The North Platte River makes the fist of the hand. The river flows north into Wyoming from Colorado and sweeps east and south in a horseshoe bend nearly 350 miles long, draining the entire southeast quarter of the state.

The Sweetwater River, one of the North Platte's major tributaries, flows in from the west, making the pointing finger. Though they couldn't see this shape from ground level on the trails they followed, most of the nearly half million pioneers laboring westward across Wyoming in the middle of the 19th century trailed along the pointing finger to its tip on a low point in the Continental Divide.

The Sweetwater River, one of the North Platte's major tributaries, flows in from the west, making the pointing finger. Though they couldn't see this shape from ground level on the trails they followed, most of the nearly half million pioneers laboring westward across Wyoming in the middle of the 19th century trailed along the pointing finger to its tip on a low point in the Continental Divide.

The North Platte River Basin covers roughly 22,000 square miles in Wyoming, about one quarter of the state. The headwaters flow from the mountains surrounding North Park, Colo., as well as the Medicine Bow and Sierra Madre and other, minor ranges of southeast Wyoming. Medicine Bow Peak, 12,013 feet high, is the highest point in the basin, while conical Laramie Peak at 10,276 feet was a landmark to westbound pioneers announcing the transition from the Great Plains to the Rocky Mountains. If starker and less picturesque than the alpine peaks of western Wyoming, the Haystack, Seminoe, Shirley, Ferris, Pedro, Granite, Casper and Laramie mountains and Rattlesnake Hills are equally dramatic. And they provide important freshwater springs and wildlife habitat for a wide expanse of open country.

Most of these ranges formed during a geologic event, the Laramide orogeny, between 70 and 40 million years ago. The Granite Mountains, southwest of Casper near the confluence of the Sweetwater and North Platte rivers, are the exception. A remnant of the larger Sweetwater Uplift--once Wyoming's largest mountain range—the Granite Mountains were dropped by faulting to a lower level between 11 and 7 million years ago, where they remain today.

Prehistoric people left traces of their lives at thousands of places across Wyoming, including hundreds of sites along the North Platte and its tributaries. The Hell Gap site near present-day Guernsey, for example, shows signs of human occupation beginning 11,000 years ago. The Casper Site, near the present Central Services building of the Natrona County School District on English Drive in Casper, was a bison-kill site 11,000 years ago. The China Wall site near the upper end of Sybille Canyon on the Laramie River dates back 5,000 years. And two sites along the North Platte near Casper, the Riverbend site in present Paradise Valley on the west side of town and a site near Edness Kimball Wilkins State Park on the east, were occupied by tribal people as recently as the early 1700s.

The early population increased, meanwhile, as people reliant on buffalo began moving to what’s now Wyoming around 500 years ago. Before the 1700s, the Shoshone made their way into Wyoming from the Great Basin in what is now Nevada. Their warlike reputation was only enhanced when they acquired horses around 1700 A.D., before their neighbors farther north and east. Only smallpox and firearms in the hands of their enemies diminished their power. By the early 1800s, the Crow and Arapaho tribes pressured the Shoshone enough that they began retreating to what are now western Wyoming, eastern Idaho and southern Montana. Other tribes, such as the Ute, traveled through the southern and southwest parts of the state.

The Arapaho, Crow and Cheyenne made their way into Wyoming from the northeast--areas that are now North Dakota and Minnesota--during the 18th century. The Lakota Sioux came to Wyoming from the northeast in the early 1800s, reaching the Bighorn Mountains around 1825. They were known for attacking and driving out other tribes, and among their few allies were the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

Early fur traders followed the route of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery up the Missouri River and across what is now Montana, but conflicts with the Blackfeet, Lakota and Arikara made this route dangerous by the 1820s. Meanwhile, during the winter of 1812-1813, partners and employees of the fur magnate John Jacob Astor returning east from the mouth of the Columbia discovered South Pass, a low point in the Continental Divide near the head of the Sweetwater River.

The route got little use, however, until fur trappers, traveling up the North Platte and Sweetwater and over South Pass to the beaver-rich streams of the Green River Basin, began using it again in the early 1820s. Their route became the main passage for traders, missionaries, settlers and others crossing the continent.

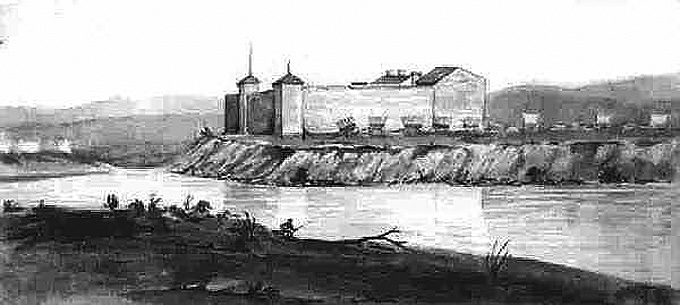

In May 1834, William Sublette and a party of traders bound for the annual fur-trade rendezvous stopped at the confluence of the North Platte and Laramie rivers--named for French trapper Jacques LaRamee supposedly killed by Indians in the area. There, Sublette built Fort William, a cottonwood stockade, to support the fur trappers and trade with high plains Indians. In 1841, it was rebuilt nearby with adobe and re-named Fort John, though already it was generally known as the fort on the Laramie, or more simply, Fort Laramie. In 1849, the U.S. Army bought Fort Laramie from the American Fur Company. It remained one of the most influential forts in the West for two generations, operating until 1890.

By the late 1830s the fur trade was dwindling. Soon, westbound emigrants began following the North Platte route blazed by the trappers. The Oregon, California and Mormon trails merged to become essentially one road along the North Platte and Sweetwater to South Pass. After reaching the divide, the trails diverged.

The Overland Trail also traversed the North Platte River Basin, coming north from what’s now Colorado paralleling modern U.S. Highway 287, briefly following the Laramie River and then swinging west around the north end of the Medicine Bow Range, crossing the North Platte River north of Saratoga and leaving the North Platte Basin at Bridger Pass, before continuing west to Fort Bridger in southwest Wyoming, where it joined the Oregon-California-Mormon Trail.

Though the North Platte River provided a course to follow and shallow muddy water for livestock and people to drink, it never served well for transport or navigation. In 1842, the adventurous, risk-taking John C. Frémont, on his way back from a quick survey of South Pass and the Wind River Mountains, capsized his inflatable rubber boat in a canyon just downstream from the Sweetwater-North Platte confluence.

In 1846, another adventurer, Francis Parkman, encountered 11 boats downstream from Fort Laramie laden with buffalo robes and beaver pelts. He wrote, "Fifty times a day the boats had been aground, indeed; those who navigate the Platte invariably spend half their time upon sand-bars."

Starting in the 1850s, several far-reaching treaties with Indian tribes were written and signed at Fort Laramie. In 1851, as many as 10,000 people, including representatives of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, Mandan, Arikara and Shoshone tribes, came to Fort Laramie at the government's invitation. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 outlined territory for the Lakota north of the North Platte River, west of the Missouri and east of the Bighorn Mountains; for the Crow west of the crest of the Bighorns; and for the Cheyenne and Arapaho between the North Platte and Arkansas rivers in what are now eastern Colorado and southeastern Wyoming.

In exchange for promises to let settlers pass through their lands and to allow the United States to build roads and military posts, the tribes were promised $50,000 in goods per year for 50 years, to be divided proportionally among them. The term was later reduced to 10 years.

In 1868, a new treaty called for all war to cease, stipulating that white men and Indians who provoked conflicts would be punished. It also set up a Lakota reservation in Dakota Territory west of the Missouri River. The Indians who settled on the reservation would be provided meat, flour and clothing and were to become farmers. They also were to allow the whites to build railroads on the plains around the North Platte River. The tribes were given permission to hunt, but not settle, in what is now Wyoming north of the North Platte River and east of the Bighorn Mountains. Any whites who wanted to settle there needed consent from the Indians.

The Arapaho were left out of the treaty, and many stayed along the North Platte River near Fort Laramie, and later near Fort Fetterman by modern-day Douglas.

The 1868 treaty coincided with the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. Built westward from Omaha, Neb., the U.P. was to meet up with the Central Pacific railroad, building eastward from Sacramento, Calif.

White settlers began arriving in Cheyenne, still part of Dakota Territory, in the summer of 1867 and the railroad reached town the following November. The tracks reached Laramie in May 1868, crossed the rest of what soon would become Wyoming Territory that year, and linked at last with the Central Pacific in Utah in May 1869. Along the way various end-of-tracks camps sprang up and many disappeared; the ones that remained became Medicine Bow, Carbon and Rawlins in the North Platte Basin, and Rock Springs, Green River and Evanston further west.

Four forts protected the railroad in Wyoming: Fort Russell near Cheyenne, still operating as Francis E. Warren Air Force Base; Fort Sanders south of Laramie; Fort Fred Steele, near Rawlins; and Fort Bridger in southwest Wyoming, a trading post since 1842. In 1868, tie hacks cut logs and floated them down the North Platte River to Fort Steele, where they were transported farther on by the railroad as construction continued.

Despite all this activity, when the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the newly created Wyoming Territory had only 8,104 non-Indian residents. During the 1870s population growth and economic activity were slow in the North Platte River basin. Settler conflicts with cattle rustlers and Indians were sporadic. Hunting excursions in the basin’s mountain ranges attracted a few visitors to Wyoming.

Cattle operations in Wyoming were concentrated in the southeastern part of the territory during the 1870s, but spread throughout the territory during the 1880s. The cattle industry boomed early in that decade, then busted after the hard winter of 1886-1887 when many cattle died, and surviving stock bore few calves. Many ranchers and investors lost money.

The 1880s brought more railroad construction to southeast Wyoming. From 1886 to 1888, the Wyoming Central Railroad was built to connect Chadron, Neb., where the Fremont, Elkhorn and Missouri Valley Railroad ended, to Lusk, Wyo. and then, on the North Platte, Douglas and finally Casper. The track was leased to F.E. & M.V. The two companies were consolidated in 1891 and were acquired by Chicago & North Western in 1903. In 1995, Chicago & North Western merged with Union Pacific.

Railroads enabled industrial and agricultural development in the North Platte Valley. The F.E. & M.V. reached Casper in 1888. The town began that year at what was originally an important river-crossing point on the Oregon Trail where there had been bridges and an army post in the 1850s and ‘60s. After the railroad arrived, it quickly became a shipping point for beef, wool, and later, crude oil and its products. Rawlins, on the Union Pacific, similarly became an important point for shipping stock.

In 1896 and 1897, gold and copper mines opened near Encampment, Wyo., at the upper end of the North Platte Valley near the Colorado border. In 1905, a railroad spur was built from Encampment to the Union Pacific at Walcott, east of Rawlins. Wyoming produced 23 million pounds of copper between 1899 and 1908, but the Encampment copper lode was mostly depleted by the end of that period.

Meanwhile, the North Platte River was being developed for irrigation. Wheatland Reservoirs Number 1 and Number 2 were built on the Laramie River in 1897 and 1898. Construction on Pathfinder Dam in Fremont Canyon downstream from the confluence of the Sweetwater and North Platte Rivers lasted from 1905 to 1911. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation continued to dam the North Platte River for irrigation through the first half of the 20th century, constructing Seminoe, Kortes, Alcova, Glendo and Guernsey reservoirs for water storage and hydropower. These federal irrigation projects serve over 226,000 acres.

In 1911 Wyoming sued Colorado over water rights in the Laramie River and the U.S. Supreme Court declared the rule of priority--"first in time, first in right"--would decide water allocation. In 1934 Nebraska sued Wyoming over water in the North Platte. The Supreme Court upheld Nebraska's rights in 1945 and made Wyoming send more water downstream. That lawsuit was reopened in 1986, resulting in a new North Platte River decree in 2001. Today, wind development is an increasingly common feature in southeast Wyoming where there are stronger winds and fewer conflicts with wildlife or other energy development than elsewhere in the state.

Today, the Platte River Basin holds Wyoming's two largest cities: Casper and Cheyenne.

While agriculture, oil and gas development and some coal mining continue along the Platte River today, recreation has become a major use of the river. Activities include backpacking in the Platte River Wilderness in the Medicine Bow National Forest along the Colorado border, white‑water rafting in North Gate Canyon south of Saratoga, soaking in the hot springs at Saratoga, fly‑fishing on the Miracle Mile above Pathfinder Reservoir or Grey Reef Station below Alcova Reservoir, kayaking in Casper's white‑water park, bicycling the Platte River Parkway trail in Casper, canoeing in Wendover Canyon between Glendo and Guernsey reservoirs, or boating, swimming, fishing and camping at any of the reservoirs.

Despite the modern changes, the North Platte River basin holds some of the most untouched country in the United States. A person who follows the ruts of the pioneer trails, or navigates some of the hundreds of miles of dirt two tracks among the rumpled mountains, may stumble upon the remains of an old corral, wagon, cabin or hunting camp tucked into the head-high sagebrush against a rock outcrop, and feel like a traveler in another time.

Resources

- "Chronological History of Fort Laramie," Ultimate Wyoming, accessed online Aug. 17, 2011 at http://www.ultimatewyoming.com/sectionpages/ftlaramie/chronohistory.html.

- Lageson, David R. and Darwin R. Spearing. Roadside Geology of Wyoming. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing, 1988, 123-126.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

- Nadeau, Remi. Fort Laramie and the Sioux Indians. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1967.

- Mattes, Merrill. Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1890. Fort Laramie National Historic Site: National Park Service, 1980, 1-19. Accessed Sept. 7, 2011 at http://www.nps.gov/fola/historyculture/upload/FOLA_history.pdf.

- O'Leary, Ray and Bob Edwards. Frontier Wyoming: The Art of Mel Gerhold. Buffalo, Wyo.: The Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum Press, 2006.

- Otteman, Aaron. "A Backcountry Trip Through Time: Part 1 of a 7 part series about the Geology of Wyoming." Wyoming Elements Magazine, Spring 2011. Accessed online Aug. 16, 2011 at http://wyomingelements.com/issues/spring2011/a-backcountry-trip-through-time/.

- Parkman, Francis. The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1883. Chapter 7. “The Buffalo,” accessed Aug. 15, 2011 at, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/OREGON/toc.html.

- Platte River Basin Plan, Final Report. Trihydro Corporation in association with Lidstone and Associates, Harvey Economics and Water Rights Services, LLC, prepared for Wyoming Water Development Commission. May 2006, accessed Aug. 15, 2011 at http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/platte/finalrept/finalrept.html.

- "Platte River Parkway," accessed Aug. 17, 2011 at http://www.platteriverparkway.org/.

- Rea, Tom. Devil's Gate: Owning the Land, Owning the Story. Norman: The University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

- Weiser, Kathy. "Legends of America: Wyoming Forts of the Old West," updated January 2011, accessed Aug. 15, 2011 at http://www.legendsofamerica.com/wy-forts.html.

Illustrations

- Map of Wyoming river basins is from the Wyoming Water Development Commission, used with thanks.

- The photo of the North Platte River near Saratoga, Wyo. is by J . Belote, from Panoramio, used with thanks.

- James Wilkins’ sketch of Fort Laramie in its adobe stage in 1849, the year it was purchased by the U.S. Army, is from Wyoming Tales and Trails, used with thanks.

- The photo of Pathfinder Dam and Pathfinder Reservoir on the North Platte River is by Tom Rea. Taken in June 2010, it shows water coming over the dam’s spillway for the first time in 25 years.