- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Separate Lands For Separate Tribes: The Horse C...

Separate Lands for Separate Tribes: The Horse Creek Treaty of 1851

In the autumn of 1850, St. Louis newspapers announced a conference to negotiate rights of passage through American Indian lands for westward-bound emigrants. Fur traders, Indian agents, mountain men, missionaries and former U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas Harvey had been pushing this idea since 1846, when the swelling number of emigrants led to increasing complaints from the tribes. Harvey lobbied for a “general council,” arguing that “a trifling compensation for this right of way” would “secure [the Indians’] friendship.”

That year, Congress had authorized a conference for all the prairie tribes west and south of the Missouri River, and north of Texas. Its stated purpose was to benefit the tribes, promising them ample compensation for depredations against them and also an annuity—“an annual present, in goods, from their Great Father.”

The government encouraged the tribes to attend with all their women and children, explaining that a large force of soldiers would be on hand to ensure their safety. The government would “divide and subdivide the country;” this would be “for the permanent good of the Indians;” to “extinguish. . .the bloody wars which have raged from time immemorable [sic].” The conference was set to begin Sept. 1, 1851 at Fort Laramie.

Difficult arrangements

Unfortunately, despite the rosy promises, conference co-commissioner David Mitchell quickly discovered that things wouldn’t go smoothly. A former Missouri River trader with the American Fur Company and the current superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis, Mitchell watched in dismay as Congress cut his funding by about half, down to $100,000 and insisted on greater concessions from the tribes.

Things looked even more dismal when Mitchell learned that cholera had broken out on the St. Ange, the steamboat bringing supplies and trade goods that year to the American Fur Company posts on the upper Missouri River. If the disease struck the tribes who lived in the settled, agricultural villages in what’s now North and South Dakota, those tribes would probably refuse to come. Or they might unknowingly bring the disease to the conference grounds. And, if they came and then learned the disease had struck back home, they might well blame the government for infecting them, and retaliate.

In late July, Mitchell traveled from St. Louis to the Missouri frontier, having made plans for his 27-wagon supply train filled with provisions, welcome gifts and foodstuffs for the tribes, to precede him to the conference. But when he reached Kansas Landing—present-day Kansas City, Mo.—Mitchell found the wagon train still on the river dock. How would he explain that?

After ordering the wagon master to proceed as quickly as possible, Mitchell pressed on across what are now Nebraska and Wyoming on the Oregon-California Trail, leaving the wagon train to come on at its slower pace. But, between Fort Kearny and Fort Laramie, he spotted just one buffalo. He had counted on an abundance of buffalo to feed the gathering. With neither the wagon train nor the anticipated fresh meat readily available, food at the treaty council would be in short supply.

Mitchell left St. Louis July 24. On August 30, he reached Fort Laramie, where thousands of restless Sioux, Arapaho and Cheyenne waited. Mitchell sought out his co-commissioner, Thomas Fitzpatrick, the renowned mountain man and now the first United States agent for the High Plains Indians, who had also lobbied for the conference. Mitchell spilled his bad news: reduced appropriations, a delayed supply train and a military escort cut by Congress’ stinginess from 1,000 to 300 men, which would never impress, much less intimidate, the Indians.

Fitzpatrick had his own bad news: The Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache—tribes of the southern plains—had refused to come. The Shoshone, however, had come in force from their homelands in the northern Great Basin and along the Continental Divide. Unfortunately, though, they had not been invited.

Even worse, while en route, the Cheyenne had attacked and killed two Shoshone warriors. Fitzpatrick also worried there would not be enough food, because game and forage were woefully inadequate at Fort Laramie. Plus, he was concerned that 300 soldiers might not be able to protect the unwalled fort on its broad, open plain.

After consulting with the assembled tribes, the commissioners decided to move the conference about 30 miles east, to the mouth of Horse Creek on the North Platte River, just east of the present Wyoming-Nebraska border. Arriving there on September 5, Mitchell assigned the Platte’s north bank to tribal encampments and Horse Creek’s west side to the traders and interpreters. The east side of Horse Creek would be the meeting grounds. The council would open on Monday, September 8.

De Smet arrives

Around sunset on September 7, Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, the venerable Jesuit missionary, arrived after escorting tribal delegates from the upper Missouri. This was the best news the commissioners could have received. Both of them had known De Smet for years. Better yet, they knew the Indians revered De Smet, who from his long travels knew traditional tribal boundaries of the northern Plains and Rockies better than any other living individual. As De Smet entered the council grounds in a carriage belonging to longtime St. Louis fur trader Robert Campbell, a crowd including Jim Bridger, the famous mountain man; the assembled military officers; and the St. Louis journalists who came to record the proceedings, gathered to greet the jovial priest.

The council opens

On Monday, September 8, the boom of a cannon announced the council’s opening and “the whole plains seemed to be covered with the moving masses of chiefs, warriors, men, women, and children,” according to the report carried in the Missouri Republican. With no small amount of fanfare, each tribal nation presented itself.

Mitchell, Fitzpatrick, De Smet and Campbell sat under the center arbor with the traders and interpreters. A Mrs. Elliott, wife of one of the military officers and the only white woman present, took a prominent seat to prove that the whites had come in peace. As required by Indian custom, the space to the east in the great council circle remained open.

After smoking the peace pipe, Mitchell opened the council. “We do not come to you as traders,” he said. “We do not want your land, horses, robes, nor anything you have; but we come to advise with you, and to make a treaty with you for your own good.” He then promised the tribes compensation for 50 years, in part for allowing “the right of free passage for [the Great Father’s] White Children” over the increasingly popular emigrant trails.

The government wanted to establish tribal territories so that the tribes’ Great Father could “punish the guilty and reward the good” for any future depredations. These divisions, Mitchell assured the tribes, were “not intended to take any of your lands away…or to destroy your rights to hunt, or fish, or pass over the country, as heretofore.” Instead, he explained that the boundaries would bring peace, and he emphasized again that the tribes would be well compensated.

Mitchell then asked each tribe to designate a single chief, along with one or two tribal members to be fêted in Washington, D.C.—a longstanding government practice with tribal representatives the government wanted to impress and intimidate with the power and might of their “Great White Father.” Finally, he tried to explain his breach of etiquette in convening the conference without gifts. “A large amount of presents and provisions” were still en route with the slow-moving wagon train, Mitchell said. He encouraged the tribes to take the next two days to “think, talk and smoke over” the proposals.

A camp of 10,000

That afternoon, the Cheyenne offered reparations for the dead Shoshone by “cover[ing] the bodies”—a ceremony of apology. After offering a feast and gifts to their former enemies the Shoshone, the Cheyenne returned the scalps of the fallen and swore they had not danced a scalp dance to celebrate the taking of the Shoshone scalps. The brothers of the Shoshone victims accepted the scalps, embraced the Cheyenne and distributed the Cheyenne gifts among the Shoshones. After more speeches from both sides, the Cheyenne and Shoshone joined together in song and dance.

That night, the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Assiniboine tribes arrived from the upper Missouri River. The arrival on September 10 of a contingent of the Crow tribe from what’s now Montana swelled the number of natives gathered to an estimated 10,000. Though no drawings or illustrations of the treaty grounds have survived, it’s clear the tribes’ encampments stretched for miles along the north side of the North Platte, and their huge horse herds would have grazed in all directions.

Still no gifts

The next morning, September 9, Mitchell scored his first achievement when the Cheyenne designated Little Chief and Rides on the Clouds to represent them in Washington, D.C. The other tribes also accepted the treaty’s outlines. But the warriors wanted their gifts. Without the supply wagons, Mitchell could not comply.

Missouri Republican Editor A.B. Chambers decried the Indians for their “begging speeches,” but Mitchell understood that, according to the traditions of the Indian trade, he was the one who was in error. Moreover, many of the tribes were in a state of what De Smet called “absolute destitution,” and had attended the conference primarily for the gifts. How could they trust a 50-year promise if the Great Father did not even feed them at his own gathering? Mitchell and Fitzpatrick pleaded for more time.

And that wasn’t the only problem. Terra Blue, a Brulé Sioux, explained that, despite the tribe’s good intentions, the Sioux, the largest of the Plains tribes, could not appoint a single chief. That was simply not the way their politics worked.

Separate lands for separate tribes

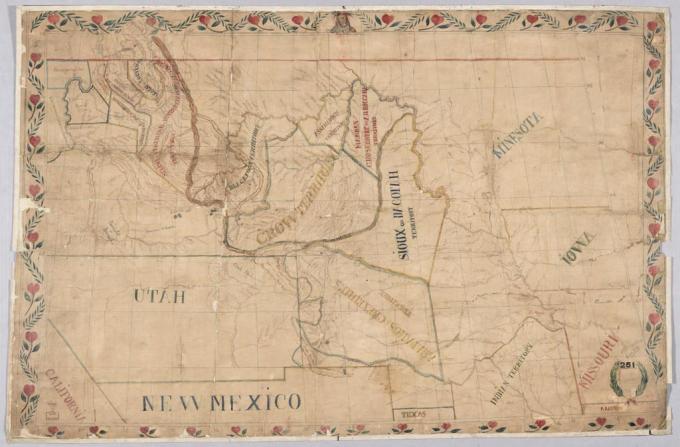

The hard work of defining tribal territories began on Friday, September 12, despite the fact that questions of compensation and tribal chiefs and representatives remained unsettled. Since no one knew the region better than De Smet and Bridger, Mitchell instructed them, with the assistance of the traders, to create a map that respected traditional homelands. The group worked through the day, finally reaching agreement at twilight.

On Saturday, the commissioners presented their map to the tribes. The Oglala Sioux complained that their hunting grounds should extend south of the Platte, which the map designated as Cheyenne and Arapaho territory. Mitchell explained again that any tribe could venture into any region, as long as their intentions were peaceful. Although the Sioux remained skeptical, the tribes finally agreed to the newly defined territories.

Terms of the treaty described Sioux lands as lying north of the North Platte as far west as Red Buttes, just west of present Casper, Wyo. The northwestern boundary would be a diagonal line from Red Buttes to the Black Hills, roughly along the Powder River. Crow lands would stretch west from that boundary, over the Bighorn Mountains to the Wind River Mountains and north into present Montana.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were assigned the country south of the North Platte, east of the Rockies and north of the Arkansas, and the Assiniboine, Hidatsa, Arikara and Mandan tribes were assigned to territory in what are now Montana and the Dakotas. And Missouri River trader Alexander Culbertson made sure that lands north and west of the Crow territory were designated for the Blackfeet, even though the Blackfeet were not present.

At the same time the treaty noted that these designations were not requirements, as long as everyone behaved; the tribes “do not hereby abandon any rights or claims they have to other lands; and further … they do not surrender” the rights to hunt in, fish in or travel through any of the other tribes’ tracts.

Baptisms

On Sunday, De Smet celebrated the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross in front of a great crowd of Indians, mixed-bloods and whites. Afterwards, he baptized the willing. Ultimately, De Smet recorded baptisms of 239 Oglala; 305 Arapaho; 253 Cheyenne; 280 Brulé and Osage Sioux; 56 “in the camp of Painted Bear.”

Nearly all were children. He also baptized 61 mixed-bloods. In return, the Sioux named him Watankanga Waokia, “The Man Who Shows His Love for the Great Spirit.”

A new chief for the Sioux

By Monday, the Oglala, Brulé, Miniconjou and other bands of Sioux still had not named a single leader for the entire tribe. Frustrated, Mitchell announced he would choose for them. He selected the Brulé warrior Conquering Bear, described in the Missouri Republican as “connected with a large and powerful family, running into several of the bands, and although no chief … a brave of the highest reputation.”

With trepidation, because the idea of a single leader was so contrary to tribal tradition, and because he himself was not yet considered a leader even among the Brulés, Conquering Bear accepted. “I will try to do right to the whites, and hope they will do so to my people,” he said, according to the newspaper. The Sioux reluctantly acquiesced to Mitchell’s decision.

The treaty signed

Finally, on September 17, twenty-one chiefs representing the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Assiniboine signed the Horse Creek Treaty. They agreed to the government’s right to “form roads and establish military posts” in Indian territory; terms for maintaining peace and for assigning reparations for losses on either side; indemnity for any prior destruction caused by the emigrants; $50,000 to each tribe for those damages; and $50,000 in annual payments per tribe for 50 years.

Mixed bloods and gifts

With the treaty signed, Mitchell and Fitzpatrick longed to disband the council. But the supply wagons had still not arrived, and they could not close the event without the distribution of the gifts. While they waited, another controversial new issue arose. The traders, most of whom had married Indian women, sought a mixed-blood allotment. De Smet called this “the sole means of preserving union among all those wandering and scattered families, which become every year more and more numerous.” Editor Chambers noted:

"The white man who has taken a squaw for a wife, however honestly and virtuously they may have lived, (and in this many of them will compare advantageously with some who claim to be civilized) is, with his wife, for ever debarred admission into society. He has shut himself out, and must reap the consequences which his own course has entailed upon him. Yet, toward the offspring of this alliance, the affections are as warm, and we believe we could with truth say as devoted, as can be found any where in civilized life."

The proponents suggested lands for the mixed-bloods near present-day Denver. But this was Cheyenne and Arapaho territory and they objected. Ultimately, the commissioners tabled the proposal, saying it fell beyond their authority. Never legally recognized, many mixed-bloods did become dispossessed.

Gifts arrive

Finally, on Saturday, September 20, the supply wagons arrived to “general joy.” The next day, De Smet noted, “men, women and children, -- in great confusion, and in their gayest costume, daubed with paints of glaring hues and decorated with all the gewgaws” hurried to the council grounds to receive their gifts.

Mitchell presented each chief with a military uniform and gilt sword before distributing the rest of the trinkets. Each band, “glad or satisfied, but always quiet,” accepted their gifts and dispersed. The remarkable 1851 Horse Creek Treaty Council was over.

Aftermath

Aftermath

But it did not keep the peace for long.

Although the government, the white emigrants and some of the tribes went on to violate terms of this historic document from time to time, this treaty did lay the groundwork for big changes in Indian-white relations in the West.

Not everyone did behave, of course. Congress unilaterally reduced the terms of the treaty from 50 years to 10. After the fact, Fitzpatrick obtained the consent of some chiefs for this change. Meanwhile, emigrant traffic on the trails remained heavy, while commercial traffic steadily increased. Despite the terms of the treaty, friction between whites and Indians was probably inevitable.

In 1854, tension erupted into warfare at a large Brulé village near Fort Laramie, where 4,000 natives awaited their overdue government annuities – the annual payments due them under the 1851 Treaty.

A dispute over a lame Mormon cow led to the deaths of 2nd Lt. John Grattan, his drunken interpreter, all 29 of his soldiers and the Brulé chief, Conquering Bear, whom Mitchell had designated chief of all the Sioux. The incident sparked an intermittent, 25-year war on the northern plains between the Sioux and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies on one side and the U.S. Army on the other.

Underneath these events, however, lay an understanding of the tribes’ territories first outlined in Father De Smet’s map. Emigrant traffic over the Bozeman Trail, a new shortcut from the North Platte to the gold fields of Montana, led to intense warfare between the tribes and the Army in the mid-1860s; these wars led, in turn, to a new treaty at Fort Laramie in 1868. A hiatus in the fighting followed. The new treaty assigned large reservations to the Sioux, Crow and other tribes, although far smaller in area than the territories first assigned in 1851.

The Treaty of 1851 enabled an objectification of Indian land, introducing the heretofore foreign concept of land “ownership” to these tribes. That non-traditional concept continues to this day, with these tribes assigned to reservations far smaller even than the ones established in 1868.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Missouri Republican (St. Louis, Mo.), October-November 1851.

- “Treaty of Fort Laramie with the Sioux, Etc., 1851.” Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. II, Treaties. Kappler, Charles J., editor and compiler. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904, accessed March 31, 2021 at https://dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/kapplers/id/26435. Full text of the 1851 treaty.

- United States Office of Indian Affairs. Annual report of the commissioner of Indian affairs, for the year 1851 (Washington, D.C.: 1851), pp. 27-29. Accessed May 23, 2012 at http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=article&did=History.AnnRep51.i0007&id=History.AnnRep51&isize=M

Secondary Sources

- Chittenden, Hiram Martin and Alfred Talbot Richardson. Life, Letters & Travels of Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet, S.J., 1801-1873. New York: Francis P. Harper, 1905. Vol. II, pp. 636-684.

- “The Encampment at Horse Creek in Indian Territory.” The Wind River Rendezvous. 12 (1982).

- Gagnon, Gregory and Karen White Eyes. Pine Ridge Reservation: Yesterday and Today. U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.: Badlands Natural History Association, 1992.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming, 2nd ed., rev. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, 12-18.

- Killoren, John J., S. J. “Come Blackrobe”: De Smet and the Indian Tragedy. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

- Kurz, Rudolph Friederich. The Journal of Rudolph Friederich Kurz: The Life and Work of This Swiss Artist. Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, 1969.

- Lazarus, Edward. Black Hills, White Justice. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

- Wischmann, Lesley. Frontier Diplomats: Alexander Culbertson and Natoyist’-siksina Among the Blackfeet. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Illustrations

- The 1987 photo by Drex Brooks of the lightning-struck tree and the cornfield beyond it at the Horse Creek Treaty grounds is from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Used with thanks.

- The picture of Thomas Fitzpatrick is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The picture of Father De Smet, taken by the Matthew Brady studio in the 1860s, is from the Library of Congress via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The image of Father De Smet’s map is from a Library of Congress online exhibit of maps, paintings and more showing the growth in European-American understanding of the West after the time of Lewis and Clark. Used with thanks.

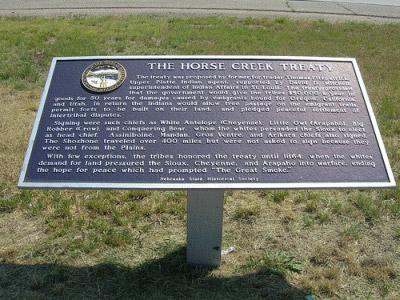

- The photo of the historical marker near the 1851 treaty grounds is by Jimmy Wayne. Used with thanks.