- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Coal Camps of Sheridan County

The Coal Camps of Sheridan County

Despite the popular image of Sheridan, Wyo. as a "cowboy" town, coal mining was crucial to its early development. Beginning in the early 1890s with the arrival of the Burlington Railroad at Sheridan, a series of coal mines were developed along Tongue River north of the town. Coal camps—small towns where the miners lived with their families—sprang up nearby.

From 1890 to 1920 population skyrocketed in Sheridan County as a direct result of the newly opened state-of-the-art coal mines along the Tongue River. The mining also attracted investors from all over the United States, brought diverse cultural groups to the region, and spawned many parallel infrastructure improvements as support systems for the mines.

Most of the miners were immigrants from central and eastern Europe. Today few buildings or other artifacts remain at the former coal camps, but the cultural impact of the mining families remains important to Sheridan today.

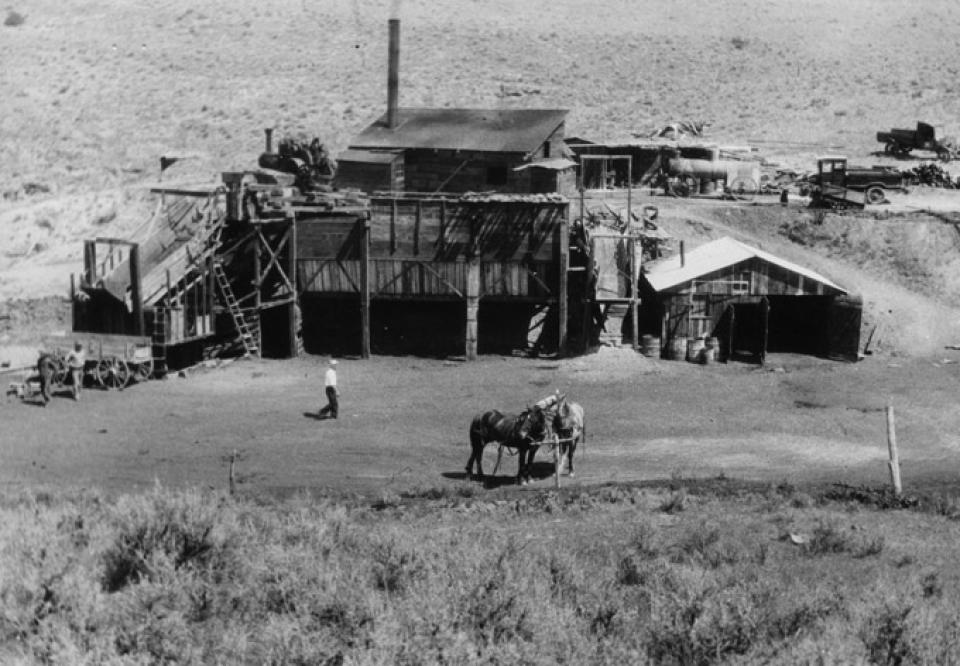

Wagon mines

Sheridan’s early settlers in the 1880s found many coal outcrops immediately north of the town. People lucky enough to own these properties often mined them in a primitive way. These enterprises were known as “wagon mines,” to distinguish them from the “railroad mines” that would come later. Locals purchased the coal directly from the landowners and either transported it themselves or paid for delivery. Coal found in “exposed seams [is used] for local farm, ranch and village use,” the Sheridan Post reported May 19, 1887, but “even then it barely proves competitive to the extensive reserves of firewood available nearby.” This would soon change with access to a larger market.

Even with the rise of the railroad mines, it seems there was plenty of business to go around. As demand created new mines, the wagon mines also prospered. Known wagon mines included Riverside, Schreibeis, Old Acme Mine, Custer Coal Company, Hart Mine, Star Mine owned by George Kuzara—many of whose descendants live in Sheridan County today—and the Welch Mine. Many wagon mines operated throughout the boom years of coal in Sheridan County from the arrival of the railroad in 1892 until after the First World War.

The Welch Mine was particularly prosperous. In fact, after the last of the larger mines shut down in 1953, it became the main supplier for the generators at Montana-Dakota Utilities’ coal-fired power plant, built in 1910.

Population explosion

In 1880, two years before the town of Sheridan was founded, there were around 100 people living along Goose Creek and its two main branches, on Soldier Creek and on Tongue River. In a 1911 pamphlet put out by the Sheridan Chamber of Commerce, the Sheridan of 1890 was described as a “struggling village of but 281 people.”

The arrival of the railroad in 1892 and the subsequent construction of the coal camps attracted thousands of workers and their families to a tight cluster of communities along the Tongue River. In 1900, Sheridan’s population was reported as 1,559. By 1910, the population had more than quintupled, to be listed as 8,408. Modern research shows that 10,000 people lived in the mining communities in 1908, more than twice as many as in Sheridan and more than doubling the population of Sheridan County. The 1911 Chamber of Commerce pamphlet bragged that, at that time, Sheridan County had “the highest density of population of any county in the state.”

The coal camps

A pragmatic confluence of resources and geography brought the Burlington and Missouri Railroad (better known as the Burlington) to Sheridan on Nov. 22, 1892. The railroad was building from South Dakota across northeastern Wyoming toward Montana and the Northwest.

The coal deposits in the Sheridan area were supposedly the most extensive ever encountered in the West—though coal deposits were plentiful, too, along the route of the Union Pacific Railroad across southern Wyoming. And like the U.P., the Burlington followed the route it did in part because the route offered abundant sources of coal. The Wyoming Coal Mine Inspector stated in 1909 that Sheridan County “contains more tons of coal than any coal field in the United States west of the Mississippi River.”

Wyoming was divided into two coal districts. District 1 was in the south along the Union Pacific Railroad. District 2 was located in the north along the Burlington and Missouri Railroad and included Sheridan County. While there may have been more coal in the Sheridan coalfields, those in District 1 essentially had a monopoly on coal markets. Any demand they were unable to meet was a result of technical limitations of a system running at full capacity. This excess demand was passed on to District 2.

The output of District 1 was phenomenal. In 1909 the mine inspector reported an “increase in production of over a million tons as compared with 1908”. The 1909 output for Carbon, Uinta and Sweetwater counties was reported to be almost 5 million tons.

By 1910, mine closures and various disasters in District 1 led to an increase in unmet demand that District 2 was able to meet. In that year, District 1 was still able to produce 5,485,533 tons while District 2 produced 1,959,919 tons, which, the state mine inspector reported, “…does not by any means represent the capacity of the district, as one fourth more coal could be produced from the mines in operation at the present time if the market demanded it.” By 1920 District 1 was producing around 6.5 million tons and District 2 was up in production to nearly 3 million tons per year.

The railroad thus became a customer for Sheridan County coal, as well as a means of delivering it to the national market. The Burlington re-engineered the furnace grates on its locomotives to accommodate the local coal’s small, sub-bituminous particles. Thanks to local, railroad and national markets, demand increased for Sheridan County coal and along with it the demand for new labor. The most efficient way for a mining operation to utilize labor was to build a “company town” in order to house, and attend to the daily needs of, the miners and their families on site.

The first example of this practice in Sheridan County began on March 3, 1893, when Sheridan investors C.H. Grinnell (a businessman, cattle-baron, and contractor who helped to dig the canal for Little Goose Creek in downtown Sheridan, erected many of the town’s substantial houses and would later become mayor), J.R. Phelan, George T. Beck (a partner with William F. Cody in the founding of Cody, Wyo. and Democratic candidate for governor in 1902), and Anson Higby formed the Sheridan Fuel Company. The company opened a mine and built a coal camp named Higby four miles north of Sheridan. When midwestern capitalist Gould Dietz became the treasurer of the company, the name of the camp was changed to Dietz.

Dietz’s superintendent, Stewart Kennedy, whose mining expertise would be relied on with the development of virtually every new mine, expanded operations. At its height, the Dietz community was made up of two permanent camps of miners and their families, and the miners operated eight mines.

In 1905 the Sheridan Press reported that Dietz employed 400 men in the summer months and 800 or so in the winter months, when demand for the fuel was higher. Carneyville, with a population of 250 made up of 50 to 60 miners and their families, was the next largest coal camp at that time.

By 1907, there were five major mines in the area, each with a sizeable camp built to house, supply, and entertain miners and their families. At first Dietz was the largest producer for the Sheridan area. The other large camps in Sheridan County were Kooi, Monarch, Acme and Carneyville, later renamed Kleenburn. In 1909 Dietz produced around 255,000tons and had 450 employees. Monarch came in second producing around 240,000 tons and having 375 employees.

Later Carneyville and Monarch overtook Dietz in production and by 1922 mining had ceased in Dietz. After that, miners continued to live in Dietz and commuted to other mines, until the camp was finally abandoned in 1937.

The immigrants

The Hotchkiss mine, a mile north of the Dietz No. 8 mine set a world record for coal production in 1925. According to Stanley Kuzara (descendent of George Kuzara) “…an average total of 19.5 tons was taken out of the mine each day for every man working at the mine” between September 1st and December 1st, 1925.

Image

Most of the miners were Polish, but a great mix of other nationalities was represented in the coal camps as well. These included American, Italian, Hungarian, Welsh, Scottish, English, Irish, Czech, Slovak, Bulgarian, Bohemian, Austrian, German, Serbian, Silesian, Montenegrin, Slovakian, Japanese, French, Greek, Swedish, Russian and Croatian miners and their families. Neighborhoods were often segregated by ethnicity and bore nicknames like “Macaroni Flats” or “Japtown.”

In the present day, there are more than ten million people of Polish descent in the U.S., making them the largest representation of Slavic people in America. While Polish people have been coming to the U.S. since it was first colonized, the largest numbers of immigrants from Poland came in three distinct waves. Unlike the first wave of Polish immigrants—Polish elites seeking political asylum—immigrants in the second wave were mostly agrarian and came seeking land.

The Poles that came to the Sheridan area to mine coal arrived between 1895 and World War I during the second wave of Polish immigration. These immigrants, who came seeking land, found themselves mostly clustered in industrial cities working low-wage production jobs, as the frontier had nearly closed. It seems logical that the Sheridan area, with its wealth of still open land, might have appealed to immigrants who found themselves in such a position.

Magda Gorska, who researched the immigration of Poles to the United States, indicated that the year 1903 is a logical guess for when Poles from the Triplevillage (Trojwies) area of Poland began immigrating to the Sheridan area. She found dozens of genealogical connections between the villages of Istebna, Koniakow, and Jaworzynka and Sheridan County. “Here it happened that this micro-nation emigrated to one of the least populous and most widespread states of the United States to a town with a few thousand citizens, taking their traditions, language, and religion with them.”

Image

While Polish culture remained cohesive within the mining population of Sheridan County, this did not alleviate inherent prejudice towards immigrants. For instance, fatality and injury reports reflected a bias under which Americans were more likely to be exonerated from wrongdoing when involved in an accident. At the same time, the wording regarding immigrants in accident reports often implied incompetence. And though locals and first-comers often saw immigrants as second-class citizens, contemporary accounts and anecdotes implied that the mining communities developed a pan-ethnic mining culture that resisted those characterizations. Residents consistently expressed pride in, and loyalty to, their community above all else.

Unions and consolidation

Booming coal demand during World War I further expanded the development of Sheridan area mines from 1914 to 1918. Workers in Dietz had been among the first in Wyoming to unionize and, once the war ended, the unions saw an opportunity to demand better wages and working conditions.

In December 1919, dozens of miners from all of the major camps were arrested by the National Guard for trying to convince men to quit working and for going against the governor’s order that no assemblies were to take place within twenty-five miles of any mine in Wyoming. They were placed in the stockade at Fort Mackenzie —a U.S. Army fort in Sheridan, founded in 1899 and now a Veterans Administration hospital. This uncompromising response from the government essentially put an end to labor organization in the camps.

In 1920, most of the smaller mines were incorporated as part of the Sheridan Wyoming Coal Company. This trend of consolidation continued when the Peabody Coal Company purchased the larger mines soon afterwards. By the 1930s, mechanization had reduced the need for labor, but increased the cost of underground mining.

World War II created a second boom that, coupled with new technologies, led to strip-mining on a massive scale as is still done today. The end of World War II, however, coincided with the development of diesel locomotives and dramatically decreased demand for coal. These factors combined to end the age of the wagon mine and the coal camp in Sheridan County. The coal-camp buildings were sold off, abandoned or disassembled. Monarch, the last large underground coal mine, closed in 1953. Many of the workers’ houses were moved into Sheridan and are still inhabited.

Economic impact

The coal camps were ultramodern by the standards of the time. Local historian Cynde Georgen writes that most had “schools, churches, hotels, stores and other amenities, and nearly all were partially or fully electrified.”

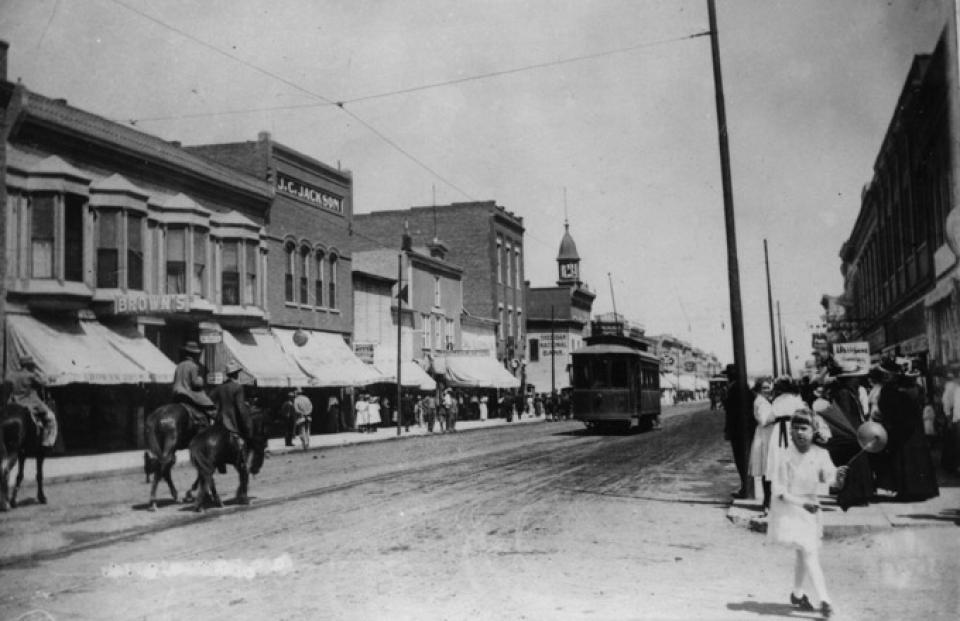

This modernization extended to Sheridan as well. Banks, power plants, irrigation projects and an electric railway system were just a few of the improvements related to the coal-based economy that directly benefited Sheridan and Sheridan County. Individuals and companies from Omaha, Chicago and New York bankrolled virtually all of these undertakings.

Image

The electric streetcar that made its Sheridan debut in 1911, for example, was completely paid for with outside capital. The railway collected fares from its riders, but its investors asked for no other contribution from the town beyond use of the right of way. With the furthest of the coal camps located some 15 miles from Sheridan, the most profitable aspect of this venture was the interurban line connecting the coal-camps to Sheridan that allowed miners to come into town on paydays, for doctor’s visits, for leisure, and even to send their children to school. The streetcar also allowed merchants to ship goods from town to the coal camps to sell merchandise to the miners and their families.

The coal-fired electric power plant completed in 1910 at Acme was one of the most advanced in the West and provided power for the mines, the coal-camps, Fort Mackenzie, Sheridan and the streetcar system. Upon seeing the completion of the Acme power plant, a Sheridan Post reporter presciently wrote, “Many years will pass; men will come and go, and the Sheridan country will undergo a great development…[this is] one of the big steps in the evolution of a desert into the greatest wealth producing section of the country.” The 1911 Chamber of Commerce pamphlet may not have been exaggerating when it described Sheridan as “one of the most progressive and promising cities in the west.”

Because of geological similarities to Sheridan County, the Powder River Basin, just east of the Tongue River drainage, is the largest coal-producing region in the country today. The coal camps of Sheridan County may be no more, but the majority of the miners moved to Sheridan with their families, unwilling to leave the area that had become home. While the coal camps and their immigrant families created a rich, local diversity of cultures, the Polish culture, in particular, remains a vital part of Sheridan’s identity today.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Hurd, J.F. Sheridan and the Sheridan Country. Sheridan, Wyo: Sheridan, Wyo., Chamber of Commerce, 1911, 16.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Carbon County, Wyo., 1880, microfilm. Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library, Wyoming Room, Sheridan, Wyo.

- Office of State Coal Mine Inspector for Wyoming. Annual Reports of the Inspector of Coal Mines for the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Sun-Leader Printing House, 1899-1930.

Secondary Sources

- Georgen, Cynde. In the Shadow of the Bighorns. Sheridan, Wyo.: Sheridan County Historical Society, 2010, 47-53.

- Gorska, Magda. “From the Triplevillage (Trojwies) to America: Facts about Highlanders' Emigration From Istebna, Koniakow, and Jaworzynka.” Draft of master’s thesis, accessed Feb. 12, 2013. http://trojwies.us/common/Magda_short.htm.

- Kuzara, Stanley A. Black Diamonds of Sheridan: a Facet of Wyoming History. Cheyenne: Pioneer, 1977.

- ______________. “The Coal Mine Camps and Mines of the Sheridan, Wyoming Area.” WyGen Web Project. Reprinted from Sheridan County Heritage, 1983. Accessed Feb. 12, 2013 at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~wymining/coal-hist-sherid.htm.

- Western, Samuel. Pushed off the Mountain, Sold Down the River. Moose, Wyo.: Homestead Publishing, 2002, 21, 29.

- Western Interpretive Services. History of the Big Horn Mine Area and the Acme Townsite. Sheridan, Wyo.: Big Horn Coal Company, 1977.

- Jones, Syd. “Polish Americans.” Countries and their Cultures website, accessed January 5, 2013. http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Pa-Sp/Polish-Americans.html.

For Further Reading

- For much more on the history of Sheridan County’s coal camps, with maps, many historic and contemporary photos and an extensive bibliography, see the interpretive plan for the Black Diamond Historic Mine Trail, prepared in 2011 by consultants TMDA for the Wyoming Historic Preservation Office and the Sheridan County Land Trust.

Illustrations

- All of the photographs are from the collections of The Wyoming Room, Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library, and are used with thanks.

- The photograph of Elmer Gentz on his front porch in Acme, 1943, is from the Gentz/Nelson collection.

- The photo of Carneyville in 1904, and the undated photographs of the inter-urban streetcar in Sheridan, the three miners on the electric engine inside the Dietz # 8 mine, and the Star King wagon mine are all from the Kuzara collection. The Star King mine, about two miles west of Sheridan, was run by George Kuzara from 1925 to 1941.

- The photograph of loaded railroad cars next to a tipple was taken at the Dietz #1 mine around 1907. The photograph is from the Juroshek collection.

- The map of the Black Diamond Historic Mine Trail is from the Sheridan Community Land Trust, used with thanks. The map appears on the interpretive signs at the sites of the former coal camps.