- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Annie, First Sailboat On Yellowstone Lake

The Annie, First Sailboat on Yellowstone Lake

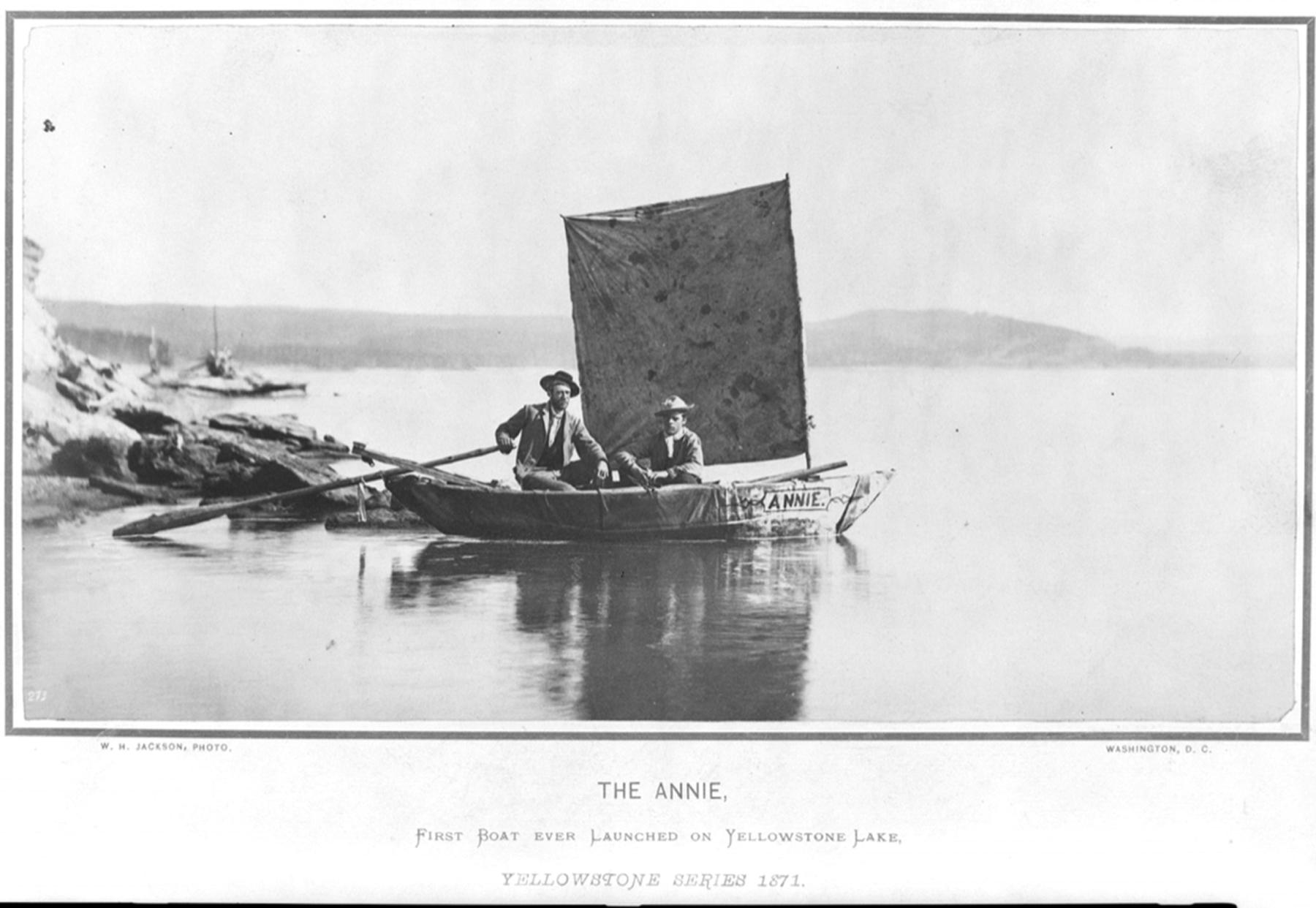

One fine summer morning two men shoved a small boat off the northern shore of a high mountain lake in Wyoming and rowed away while members of their party on land gathered to watch. Ordinarily, this event would be hardly worth mentioning, except the body of water was Yellowstone Lake and the year was 1871. As far as anyone knows, no one before had ever entered its waters in a boat—and certainly not in a sailboat.

Image

The expedition

The two men were members of the Hayden Geological Survey, an official exploration funded by the U.S. Congress for the purpose of gathering information on the mineral, economic and topographic resources of the Yellowstone Basin, a place of mystery and rumors. It was one of four government surveys operating in the West that year; in 1879 they would combine to become the U.S. Geological Survey.

Image

The two men were heading for a prominent island several miles offshore to see what they might find. While all members of the party celebrated the boat’s successful launch, they worried about weather. Winds could roil the waters with little warning on that high mountain lake, whipping the surface into furious whitecaps.

Geologist, physician and paleontologist Ferdinand V. Hayden designed the skin-on-frame boat. Woodworkers at Fort Ellis, near today’s Bozeman, Montana, had built it to specifications, then disassembled it plank by plank to be packed up on a mule to the lake’s northern shore. Once there and reassembled with heavy canvas covering the frame, a rudder, oars fashioned from timber on site and a blanket strung between two masts for a sail, the craft was ready. Although there are contradictory descriptions about its size, including several by the designer himself, “our little bark” Hayden reported, was somewhere between 11 and 12 feet long by 3 ½ and 4 ½ feet wide, and 22 inches deep.

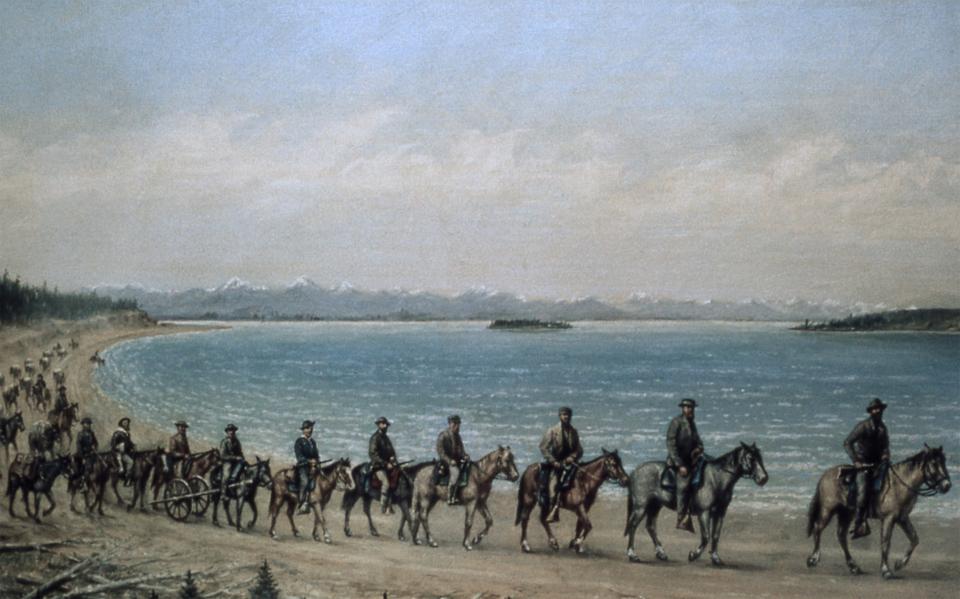

Hayden’s team of more than 30 men included photographer William Henry Jackson, artists Thomas Moran and Henry Elliott, scientists, soldiers providing a military escort, a cook, guides and several sons of prominent congressmen Hayden had invited on purpose to join the adventure. In addition, the expedition included horses, pack mules and a two-wheeled cart odometer to measure distance. And there was a portable boat.

After leaving Fort Ellis in mid-July, the group followed the Yellowstone River south and upstream toward the lake, taking their time to camp, survey and collect materials along the way. Hayden had pressed the Grant administration and the Reconstruction Era congress for an expedition to explore Yellowstone. He wanted to document a landscape full of otherworldly geological features—vents spewing constant steam, periodic lofty geysers, wildly colorful hot springs, mud volcanoes, and even stories of petrified trees. Explorers, trappers, miners, hunters and natives had reported all of these wondrous features.

Image

And if what he found lived up to the fantastic descriptions, Hayden wanted Congress to preserve the region and not let it fall prey to land speculators and commercialization. (Like most Americans at the time, he had no trouble with the idea that in order for the U.S. government to take possession of Yellowstone, Indigenous people would have to be dispossessed of still more territory in addition to most of a continent already lost.)

Traversing Yellowstone

Stopping to camp for a few days at Mammoth Hot Springs (“a high white mountain, looking precisely like a frozen cascade”), Hayden noted commercialization already happening. Two men “with a foresight worthy of commendation” had “preempted” 320 acres covering most of the hot springs area, anticipating that when the Northern Pacific Railroad was completed, the area “will become a famous place of resort” for those seeking the pleasures and medicinal healing properties of the terraced hot springs and pools.

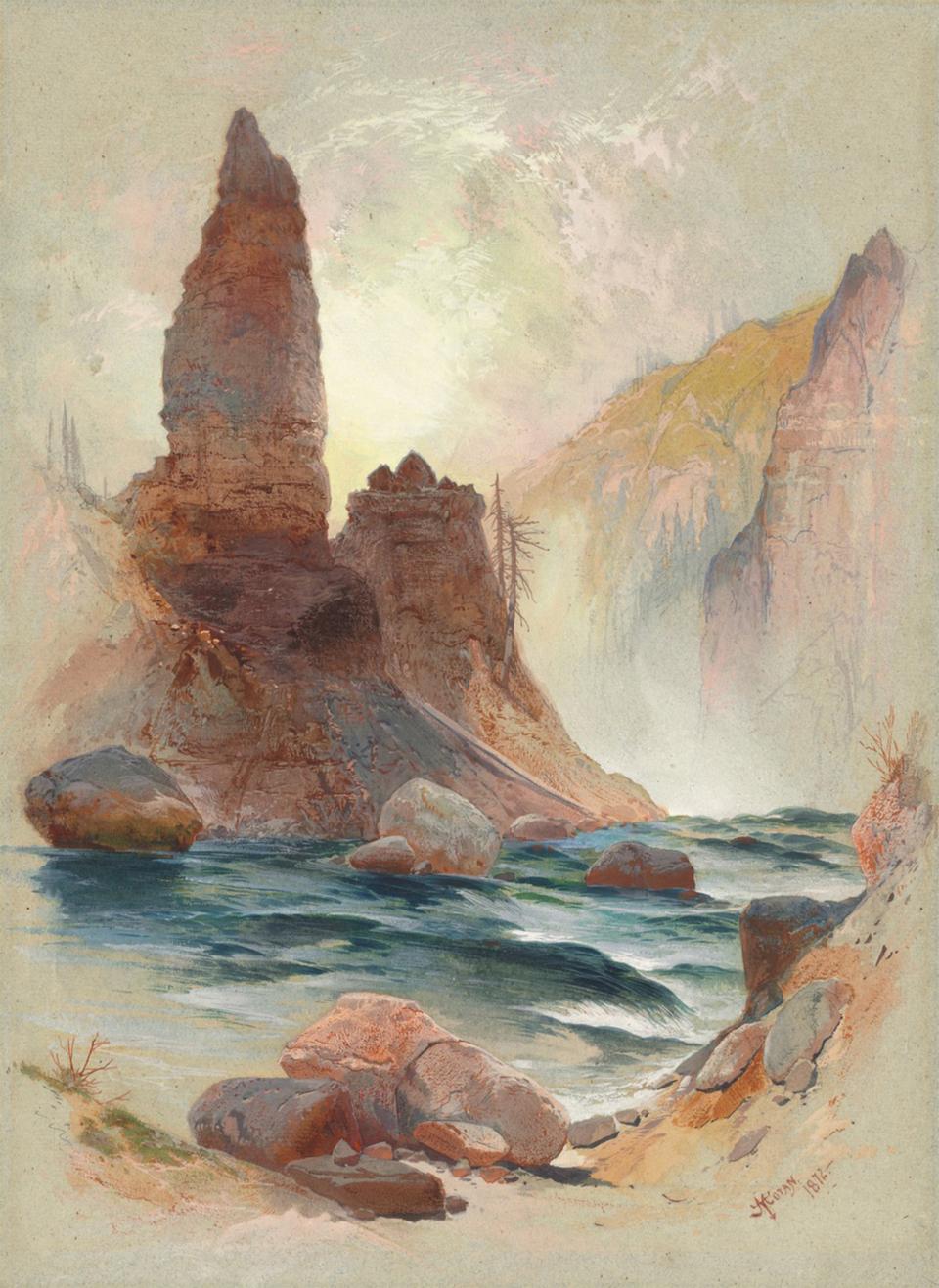

Leaving Mammoth and resuming the trek toward the lake, Moran took time to climb down and sketch the Tower Falls area. Farther upriver, the party paused for several days at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Here Moran and Jackson spent their time sketching and photographing the canyon and lower and upper falls of the river.

The scenery was breathtaking. “The well-known landscape painter Thomas Moran who is justly celebrated for his exquisite taste as a colorist,” Hayden remarked, “exclaimed with a sort of regretful enthusiasm, that these beautiful tints were beyond the reach of human art.”

As the party continued south, the forest thickened with downed lodgepole pines and bramble, making travel difficult. But there were also barren areas of thermal activity to explore along the way, and not without certain hazards: "The entire surface is perfectly bare of vegetation and hot, yielding in many places to slight pressure. I attempted to walk about among these simmering vents, and broke through to my knees, covering myself with hot mud, to my great pain and subsequent inconvenience," Hayden wrote of the mud volcano area at the southern end of what would become known as the Hayden Valley.

Image

Image

A voyage on the lake

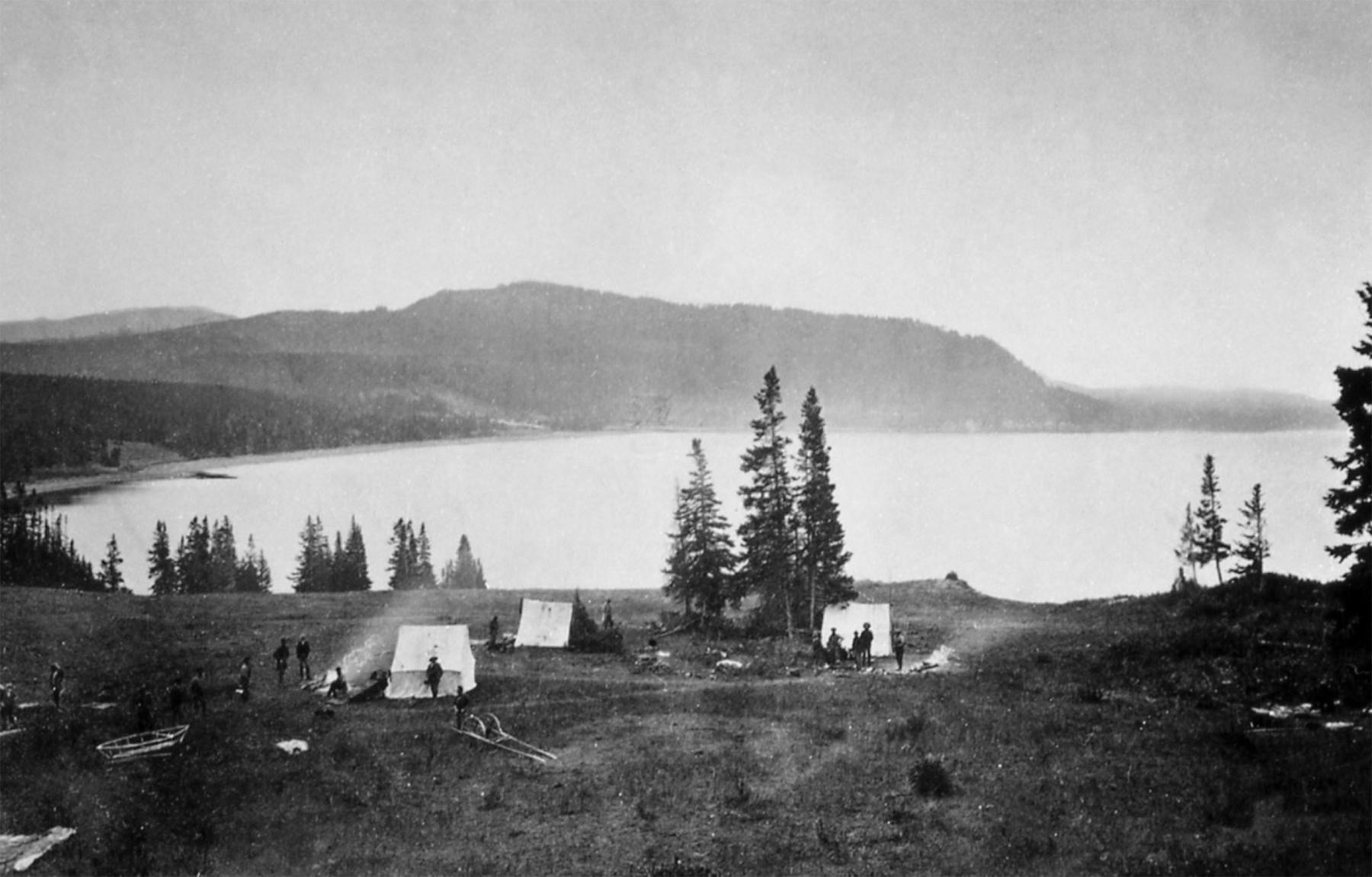

Finally, the party reached the north shore of the lake and set up camp, where “we had one of the finest views of this beautiful sheet of water.” Here, they reassembled the boat.

Annie was named for Anna Dawes, the daughter of Henry L. Dawes, a congressman whose efforts had proved critical for funding the expedition. (In Dawes’s later career in the Senate he authored the Dawes Act, which provide a systematic way for the government to divide Indian lands into individual parcels that could be easily sold off, weakening tribal power and control.) Dawes’s son Chester was along on the expedition and is shown in a William Henry Jackson photograph with Jim Stevenson in the boat. Some later reports refer to the boat as Anna.

Image

Stevenson, who was Hayden’s assistant, and Elliott, a sketch artist, were the two men who successfully made their way out to the island and back, the weather having cooperated on that summer day. Hayden promptly named the island for Stevenson, “as he was undoubtedly the first human that ever set foot upon it ....”

For the duration of the expedition, Annie assisted in hydrographic, topographical and pictorial surveys of the lake and surrounding peaks. The boat performed a “most excellent service” Hayden wrote for Scribners Monthly, adding,

“…the entire length and breadth of the Lake was navigated many times. Soundings of the Lake were made in every direction, and the greatest depth discovered was three hundred feet. Messrs. Elliott and [E. Campbell] Carrington made a survey of the shore-line from the boat, and, with the numerous bays and indentations, they estimated the distance to be about one hundred and seventy-five miles. So far as beauty of scenery is concerned, it is probable that this lake is not surpassed by any other on the globe.”

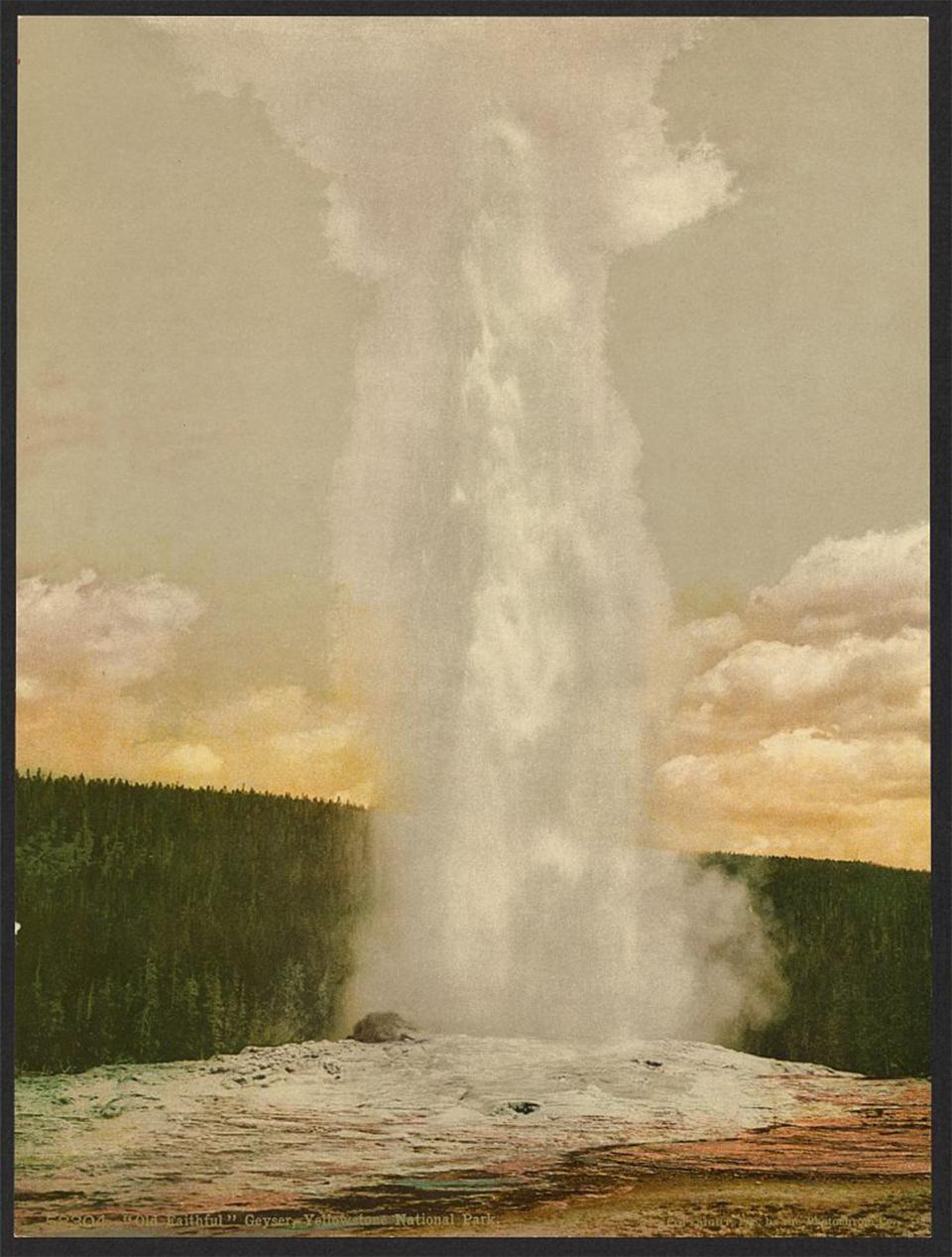

After leaving the boat to continue scouting the waters of Yellowstone Lake, Hayden led a small group, including Moran and Jackson, west over the “high divide between the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers” to the Firehole Basin. Farther south, the men explored the geyser areas and witnessed Old Faithful, Castle Geyser, “mud puffs” and other features of the steaming landscape. After exploring, photographing, sketching and recording their observations, the party returned to Yellowstone Lake.

Image

Image

A national park

In 1872, less than a year after Hayden completed his expedition, Congress passed the law creating America’s first national park. The Department of the Interior was to manage it. For the next few years, it remained a wilderness accessible only to intrepid visitors, until 1883 when Jay Cooke’s Northern Pacific Railroad was completed, bringing tourists to Livingston, Montana Territory, just 50 miles north of the park’s northern boundary. For a few years after the government created the park, officials allowed the commercial enterprise Hayden had mentioned to continue at Mammoth Hot Springs.

Image

Although the new national park prohibited tribes from hunting on their traditional communal lands, poaching by others increased alarmingly, to the point that it was put under the authority of the U.S. Army for protection in 1886. The army established a base at the foot of Mammoth Hot Springs to house troops, and from there they managed the park for more than three decades. Many of their structures are still used today.

The portable boat did not return from the shores of Yellowstone Lake at the end of the expedition. Instead, it was left disassembled and cached somewhere on its northern shore, the men not wanting to pack it back out. Hayden and most of the party returned north through the Mirror Plateau, east of the Yellowstone River. Another group, including Moran, traveled back by way of the Madison River.

Today, visitors can see only a few sailboats on Yellowstone Lake, although it attracts plenty of power boats, hard-shell canoes and kayaks during the summertime. Occasionally watchers can even spot skin-on-frame folding kayaks—some with traditional wood frames and rubberized skin, some using exotic carbon fiber frames and lightweight skin material. These portable and very seaworthy craft, often fitted with sails, can be packed up and transported almost anywhere, just like the Annie. But for most sightseers, a commercial boat, the Lake Queen motoring out of Bridge Bay Marina in the northern part of the lake, is a good way to get out on the water and to see Stevenson Island up close.

While there is no evidence he ever sketched or later painted it, Moran’s Aug. 4th diary entry records a direct experience he had in the Annie: “…took the Boat to the springs farther round the lake & had a hard pull to get back as the Lake was rough & the wind against us.”

Throughout the 1871 expedition, the Annie proved her capabilities while completing her remarkable mission.

[Editors’ note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support which in part made publication of this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Scribners Monthly. “The Wonders of the West-II” 3 (1871-72). HathiTrust, 388-396, accessed April 15, 2024 at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnyb6x&view=1up&seq=400.

- United States Department of the Interior. National Park Service. “Thomas Moran’s Diary,” accessed April 15, 2024 at https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/thomasmoransdiary.htm.

Secondary Sources

- Mangan, Elizabeth U. “Yellowstone, the First National Park.” Library of Congress, 1973, accessed April 15, 2024 at https://www.loc.gov/collections/national-parks-maps/articles-and-essays/yellowstone-the-first-national-park/ .

- National Gallery of Art. “Thomas Moran,” accessed April 15, 2024 at https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1730.html.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Art and the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871,” accessed April 15, 2024 at https://americanexperience.si.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Art-and-the-Hayden-Geological-Survey-of-1871_.pdf.

- United States Department of the Interior. National Park Service. “Early History of Yellowstone National Park and Its Relation to National Park Policies,” accessed April 15, 2024 at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/yell/cramton/sec5.htm.

- _________________________________. U.S. Geological Survey. Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden and the Founding of the Yellowstone National Park (Glasgow: Good Press, 2023). Kindle Edition, 9-53.

- ________________________________. National Park Service. “Jay Cooke,” accessed April 15, 2024 at https://www.nps.gov/people/jay-cooke.htm.

- Yellowstone Forever. “Legendary Teamwork of Moran and Jackson Puts Yellowstone on the Map,” Oct. 29, 2019, accessed April 15, 2024 at https://www.yellowstone.org/legendary-teamwork-of-moran-and-jackson-puts-yellowstone-on-the-map/.

For further research

Maps from the 1871 Hayden Geological Survey can be found here:

Illustrations

- William Henry Jackson’s photos of the terraces at Mammoth Hot Springs and the Earthquake Camp are from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The Thomas Moran watercolor and pencil sketch of the Mammoth terraces is from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Used with thanks.

- Moran’s watercolor, gouache and pencil sketch of the tower at Tower Falls is from the National Gallery of Art.

- Jackson’s photo of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, his painting of the Hayden Expedition on the march and Moran’s painting of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone are all from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- Jackson’s photo of the Annie under sail (more or less) and his photo of Old Faithful are from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.