- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Tom Horn: Wyoming Enigma

Tom Horn: Wyoming Enigma

Tried, convicted and hanged in 1903 in Cheyenne for a murder he almost certainly did not commit, Tom Horn was an enigmatic range detective in the employ of ranchers who controlled large tracts of land in southeastern Wyoming and northwestern Colorado.

Even today, he has a reputation as a killer hired to exterminate cattle rustlers, but in his own words his work was “that of a detective”—to patrol the range and look for cattle that were out of place—that is, away from the customary ranges of their owners.

Horn remains controversial for two reasons: first, because of doubts that he actually killed 14-year-old Willie Nickell at Iron Mountain, northwest of Cheyenne, on July 18, 1901, and second, because of the questionable nature of his trial. By then, he already had led an eventful life in a West that was evolving from frontier territory to a place more settled and economically developed.

Born in Scotland County, Mo., in 1860, Horn left home at the age of 14, according to his own account, and ended up in Arizona Territory by way of various livestock and stage-driving jobs, in Kansas and New Mexico. He was smart, tough and had an excellent ear for speech, quickly picking up Spanish and, later, some of the Apache language.

While still in his teens, he went to work for Al Sieber, chief of scouts for the U.S. Army in its campaigns against the Apache. In 1886, Horn escorted the Army column that captured the famed Apache leader, Geronimo, for the final time.

In 1891, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency hired Horn to pursue bandits who had robbed the Denver and Rio Grande train near Cañon City, Colo. Over the next decade, Horn did other jobs for the Pinkertons.

Tom Horn came to Wyoming in the late 1880s or early 1890s, his services apparently solicited secretly by prominent ranchers. Ranchers Ora Haley, John Coble, Coble’s partner Frank Bosler and, probably, the huge Swan Land and Cattle Company almost certainly were among his employers.

At that time the owners of large herds of cattle were struggling to survive in a business that just a decade before was making them rich. In the 1880s, they ruled their ranges like private fiefdoms. Most had little concept of the true carrying capacity of those ranges, however, and stocked them with more cattle than the land could support.

Cattle prices peaked in 1882, drawing more money to the industry and bringing more cattle to the land. Soon there was a beef glut. Prices began to fall, yet no one could think of anything to do but acquire even more cattle—weakening the ranges further and driving prices farther down. When a bad drought in 1886 was followed by the terrible winter of 1886-1887, the cattle business was nearly wiped out.

Many ranchers went out of business. Many longstanding cowboys and more recent immigrants to the Territory took up homesteads and other small land claims of their own. The once-powerful Wyoming Stock Growers Association found both its membership and its revenues from dues shrinking drastically.

Some of the cattlemen who survived began publicly blaming all their problems on cattle theft. Rustling was definitely a factor, but only one of many difficulties facing ranchers who owned large tracts of land. Claiming they were forced to make an example of thieves, cattlemen lynched homesteaders Ella Watson and Jim Averell on the Sweetwater River in 1889. When that crime went unpunished, leading men of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association led a private army of 50 men into Johnson County in northern Wyoming in 1892 to kill suspected rustlers there. They murdered two men, but those crimes, too, went unpunished.

Association Secretary Thomas Sturgis echoed a viewpoint common among the association’s members, and often repeated by newspapers under their control, when, in 1886, he blamed the problem on sympathetic juries that would not convict cattle thieves:

[I]t is very difficult to get an indictment from a grand jury [even] with pretty definite evidence as to the guilt of the party charged with stealing cattle. … There seems to be a morbid sympathy with cattle thieves both on the bench and in the jury room….[

It would be impossible for the Association ... to undertake to bring the parties referred to, to justice. In the first place, we have no money at our disposal. … Circumstances have forced cattlemen to look to themselves for protection outside of any association.…

Public outcry against the Sweetwater lynchings and the Johnson County Invasion was widespread. After the invasion, in the elections of 1892, the cattlemen’s political hold on the state weakened. And suddenly sheepmen, too, were bringing their flocks onto ranges cattlemen had long thought of as their own. But many cattlemen’s attitudes toward their difficulties appear not to have changed much. They still thought rustlers were the cause of their woes, but they began to deal with those woes in secret. Enter Tom Horn.

While no fixed date has been established for Horn’s arrival in Wyoming, the correspondence of U.S. Marshal Joseph P. Rankin shows Horn was in the state by May 1892, when Rankin deputized him to investigate a murder in the aftermath of the Johnson County invasion. Rankin believed Horn was working for the Pinkertons at the same time.

By 1895, Horn was most likely working for private interests when he was suspected of murdering two settlers. The first, William Lewis, was an immigrant from England who settled on Horse Creek northwest of Cheyenne. In previous years, Lewis had been jailed for stealing clothing and cheating a boy at a faro game. At the time of his death Lewis was suspected of cattle theft, and was under a court order to refrain from butchering cattle.

On July 31, as Lewis was loading a skinned beef into a wagon, three shots hit him.

Tom Horn was suspected, and subpoenaed to appear at the coroner’s inquest in Cheyenne. More than a dozen witnesses testified, including Horn and rancher William L. Clay. Clay and Horn both testified that Horn had been in Bates Hole south of Casper at the time of the murder. Horn was exonerated.

Two months later, Fred U. Powell, who homesteaded west of the Laramie Range and in Albany County, was shot and killed. Powell’s hired hand, Andrew Ross, was the only other person on the ranch at the time. Ross testified at the inquest that he heard one shot, found his employer’s body and fled.

Powell’s wife, Mary, and young son, Billy, were in Laramie at the time of the murder. But at the inquest Billy was in court and, upon seeing Tom Horn, cried out, “Mama, that’s the man who killed Daddy.” How the boy could make a statement like that when he was not present at the murder remains a major question, but the prosecutor in Horn’s trial years later would use it against the detective. Despite Billy’s sudden outburst, Horn was not charged in connection with the Powell murder.

But these crimes, and rumors of other killings, had by 1895 already solidified Horn’s intimidating reputation.

In 1914, Philadelphia physician Charles Penrose, who briefly accompanied the 1892 invasion of Johnson County but left before the killing began, wrote his recollections. Penrose included a vivid description of Horn as he was in 1895, as told to him by W. C. “Billy” Irvine, president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association during the 1890s.

At the time, Wyoming Governor W.A. Richards was experiencing cattle thefts on his own ranges in northwest Wyoming. As Penrose recounts Irvine’s story, Richards and Irvine encountered each other walking toward the Capitol, where both the governor and the Stock Growers Association had offices at the time:

When we reached the building he said, “Come into my office; I want to see you.” He immediately laid his troubles at the ranch before me [Irvine told Penrose], and we discussed the situation quite fully.

He finally said he would like to meet Tom Horn, but hesitated to have him come to the Governor’s office. I said, “Stroll in my office at the other end of the hall at three o’clock this afternoon, and I will have him there….” [At the meeting] the Governor was quite nervous, so was I, Horn perfectly cool. He talked generally, was careful of his ground; he told the Governor he would either drive every rustler out of Big Horn County, or take no pay other than $350 advanced to buy two horses and a pack outfit. When he had finished the job to the Governor’s satisfaction, he should receive $5,000, because, he said in conclusion, “whenever everything else fails, I have a system which never does.” He placed no limit on the number of men to be gotten rid of. This almost stunned the Governor. He immediately showed an inclination to shorten the interview.... [After Horn left] the Governor said to me, “So that is Tom Horn! A very different man from what I expected to meet. Why, he is not bad‑looking, and is quite intelligent; but a cool devil, ain’t he?”

Horn continued to work as a detective through the late 1890s. In 1900, many historians have concluded, Horn murdered two suspected cattle thieves, Matt Rash and Isom Dart, in Brown’s Park, where the Colorado, Utah and Wyoming borders intersect. A foreman for the ranchers who hired Horn was quite firm, in an account written down 20 years later, that Horn had done the crimes. The crimes received little notice in Wyoming.

After the Nickell murder in July 1901, the county commissioners in Cheyenne hired sometime stock detective and sometime deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors, to investigate that crime.

In December 1901, LeFors received the first of several letters from a former boss in Miles City, Mont., that spoke of a need for a range detective to investigate rustling in the area. LeFors forwarded the letters to Tom Horn, apparently to induce him to respond.

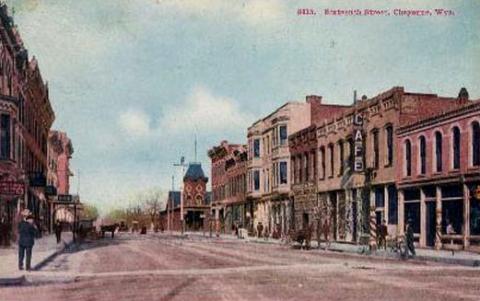

Apparently taking the bait, Horn went from John Coble’s place in Bosler where he had been living at the time to Cheyenne on Saturday, Jan. 11, 1902, probably stayed up all night drinking and accompanied LeFors to the U.S. Marshal’s office on 16th Street (now 210 West Lincolnway) the next morning.

LeFors secreted two people, a stenographer and a witness, behind a locked door. Over the course of a couple of hours, LeFors led Horn into making a series of incriminating remarks about the Nickell killing. The most damaging was, “It was the best shot that I ever made and the dirtiest trick I ever done.” The stenographer recorded and transcribed these comments, which were used as key evidence in Horn’s trial.

The trial, held just before the November 1902 election, was tainted by politics. Prosecutor Walter R. Stoll and presiding judge Richard Scott were both up for re-election. Public interest was intense, and the event received widespread newspaper coverage in Wyoming and Colorado.

Horn’s lawyers included some of the best known in the state, including John W. Lacey, a former chief justice of Wyoming Territory, and T. Blake Kennedy, later a federal judge. But they had a client who on the stand became his own worst enemy. Horn’s oversized ego apparently caused him to challenge the prosecutor, and Horn’s own testimony destroyed an alibi placing him 20 miles from the site of the murder just an hour after it happened.

Horn’s lawyers closed by emphasizing that all the evidence was circumstantial, and that Horn’s supposed confession was nothing but drunken boasts.

Stoll, in closing arguments for the prosecution, posited that Horn killed Willie Nickell in order to keep the boy from reporting on his presence in the area. The jurors accepted this as a motive, but in all likelihood, given the anti-Horn press coverage and their poorly enforced sequestration, they made up their minds before they left the courtroom to deliberate.

Horn was hanged at the Cheyenne jail on Nov. 20, 1903. Although he might have murdered Willie Nickell, he probably did not. There was no direct material or testimonial evidence to prove that he did commit the crime.

The confession he gave to LeFors was given while he was drunk, Horn was a known boaster, and neither LeFors nor any other authorities tried to investigate anyone else. (The Nickells, for example, had been feuding for years with their neighbors the Millers. A strong case can be made that Jim Miller mistook Willie Nickell for his irascible father, Kels, that morning in 1901, and shot him to settle old scores.) Horn, it seems clear, was convicted because his reputation made him an easy target for the prosecution.

Horn remains an enigma because of the lingering controversies over whether he killed Willie Nickell and over the nature of the trial.

Even more important than questions of his guilt, however, was the political shift in Wyoming shown by the fact that Horn, friend of the barons, was convicted and executed. Their power, once substantial, was on the wane. Ordinary Wyoming citizens were growing intolerant of their heavy-handed actions.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Horn, Tom. Life of Tom Horn: Government Scout and Interpreter: a vindication. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964. First published 1904.

- Penrose, Charles. The Rustler Business. Douglas, Wyo: The Douglas Budget, 1982, 55-56. Penrose wrote this account in 1914.

- Clerk of the First District Court, Cheyenne, Wyo. Transcript of the Inquest into the Murder of William Nickell 1901.

- State of Wyoming v. Tom Horn, 1902.

Secondary Sources

- Donahue, James, ed., Wyoming Blue Book: Guide to the County Archives of Wyoming, Vol. V, Part I. Centennial Edition. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming State Archives, Department of Commerce, 1991, p. 496.

- Mokler, Alfred J. History of Natrona County, Wyoming. New York: Arno Press, 1966, 221-223. Reprint; first published in 1923.

- Urbanek, Mae. Wyoming Place Names. Boulder, Colo.: Johnson Publishing Company, 1967, 21.

- Carlson, Chip. Tom Horn: Blood on the Moon. Glendo, Wyo: High Plains Press, 2001.

- Burroughs, John Rolfe. Guardian of the Grasslands: The First Hundred Years of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. Cheyenne: Pioneer Printing and Stationery Co., 1971, 154.

- Krakel, Dean, The Saga of Tom Horn. Laramie: Powder River Publishers, 1954.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965. 163-194, 372-374.

For Further Reading

- Henry, Will. I, Tom Horn. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996. A highly entertaining fictional account.

Illustrations

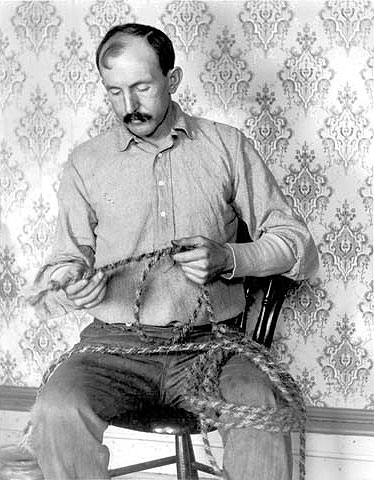

- The photo of Tom Horn braiding rope in the office of the Cheyenne Jail, 1902, is from the Wagner Collection, Wyoming State Archives. Used with thanks.

- The photo of 16th Street (now West Lincolnway) in downtown Cheyenne early in the 20th century is from Wyoming Tales and Trails, with thanks. The second-story bay window in the building on the left was the location of the U.S. marshal’s office, where Joe LeFors lured Tom Horn into making his confession.