- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Inland Empire: The Swan Land and Cattle Company...

Inland Empire: The Swan Land and Cattle Company Ltd.

For the 68 years it lasted, the Swan Land and Cattle Company was managed first by a lavish spender and freewheeling speculator. Then it was rescued, and later run for a much longer stretch by a conservative, cost-conscious Scot unafraid to make himself unpopular.

Though not born rich, the ranch’s founder, Alexander Swan, owned or held an interest in at least 20 successful business enterprises by the time he was in his early fifties. Capitalized at around $440 million in today’s dollars, these businesses mostly involved cattle ranching, fattening, breeding and shipping, but also included investments in banks, railroads, various small businesses and some city real estate.

Swan was persuasive and seems to have been unable to resist a promising prospect; this combination attracted dozens of investors and fueled his quest for more opportunities. At his peak in the early 1880s, he may have been the best-known man in the cattle business throughout the U.S. and overseas.

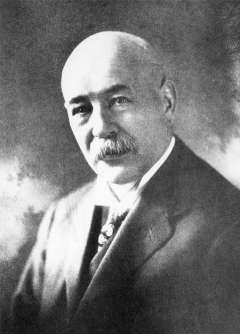

John Clay Jr., a Scot who settled in the U.S., was prosperous, although he probably never owned or invested in as many businesses as did Swan. His enterprises, primarily in agricultural banking and the livestock commission business, were, like his financial behavior, stable and cautious. Clay suffered occasional setbacks in his long business life but unlike Alexander Swan, he never “crashed.”

Alexander Swan

Alexander Hamilton Swan built the empire that became the Swan Land and Cattle Company. Born in 1831 in Carmichaels, Pa., near Pittsburgh, Swan settled in Indianola, Iowa, in 1862. There he and his wife, Elizabeth Richey Swan, had two children, William R. and Louise.

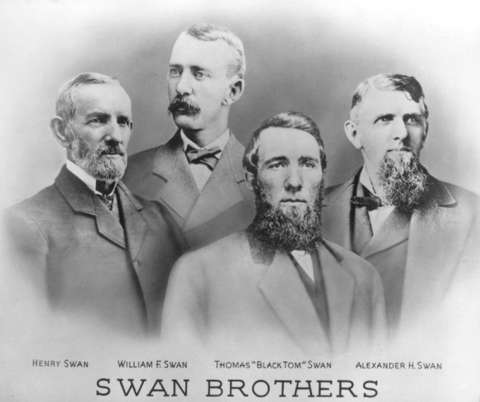

In 1874, Swan and his family moved to Wyoming Territory and filed on a homestead on Chugwater Creek, near present Chugwater, Wyo. Swan joined with his older brother, Thomas, to form the Swan Brothers partnership. During the next six years, the partnership bought land and cattle.

In 1876, Swan was elected president of the Laramie County Stock Association, precursor to the powerful Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association. The next year, he served one term in the Wyoming territorial legislature.

Swan Brothers expanded their partnership in 1880 to include Joseph Frank of Chicago, Ill., a wealthy Prussian immigrant. That year Alex also joined the opulent new Cheyenne Club, run by and for prosperous cattle ranchers.

In 1881, Swan Brothers and Frank incorporated as the Swan and Frank Company, and acquired another shareholder, Joseph Rosenbaum. Rosenbaum and his brothers owned a prominent livestock commission house in Chicago, and handled a significant amount of Swan business.

The same year, Swan organized the National Cattle Company, whose shareholders were the Swans; the Rosenbaum brothers; Amasa R. Converse, an important Wyoming rancher; and members of the Snydacker family of Chicago. Godfrey Snydacker was a wealthy banker.

In 1882, his last year as president of the Stock Growers’ Association, Swan organized the Swan, Frank and Anthony Cattle Company. The Swans, Joseph Frank, Charles E. Anthony of Peoria, Ill. and Zachariah Thomasson were shareholders, with Charles Anthony contributing most or all of the money. Thomasson had been the general manager of the original Swan Brothers partnership.

The capitalization of these three corporations totaled $1.9 million, or $43.2 million in today’s money, enabling Alex Swan to purchase more cattle and ranches.

Thomas Lawson, a Scottish agricultural expert living in the U.S., traveled to Wyoming Territory in 1882 and inspected Swan’s ranches. Lawson was manager of the Missouri Land and Livestock Company, which had Scottish investors. It is unclear whether Swan invited Lawson or if Lawson, representing potential investors in Scotland, had initiated the contact with Swan.

In his Dec. 1, 1882, report to the Scots, Lawson estimated that Swan’s three corporations were grazing nearly 100,000 head of cattle on about 4.5 million acres.

Cattle prices had been high for more than a decade. From about 1870 through the early 1880s, a steer that cost less than $2 to raise sold for between $35 and $60. Labor was cheap. On the millions of acres of good grass in present Colorado, Wyoming and Montana, stockmen were grazing large herds on the open range, paying nothing for its use.

Financial centers in New York, Boston, London and Edinburgh buzzed with the excitement of huge returns, and every time a British investor reported his profits—sometimes 80 to 100 percent in a single year—the rush sped up to run cattle in the American West.

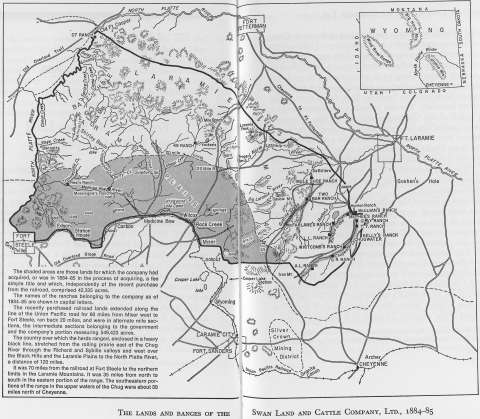

Alexander Swan owned or controlled a vast territory, though somewhat less than Lawson’s estimate. A map from the mid-1880s, possibly Lawson’s, shows Swan’s holdings and later the company’s: a rough rectangle about 110 miles wide, east to west. These borders were the Laramie Mountains on the north, and on the south, the main line of the Union Pacific Railroad running west through Medicine Bow to Fort Steele on the North Platte River.

The east side was about 35 miles north to south; mostly ranches along Chugwater Creek. The west border ran about 70 miles along the North Platte River from Fort Steele north to Bates Hole south of present Casper. This area measures approximately 5,775 square miles, or 3.7 million acres—nearly 6 percent of Wyoming.

Swan continued active in the Stock Growers’ Association and, in 1884, clashed with Secretary Thomas Sturgis over the notorious Maverick Bill. This bill legalized the Association’s ongoing practice of selling unbranded, motherless calves at roundups, and pocketing the proceeds. Swan considered the bill unjust and instructed his lawyer to work against it.

The Swan Land and Cattle Company Ltd.

In spring 1883, the year before the Maverick Bill conflict, Swan traveled to Edinburgh, Scotland, to meet with potential investors. The cattle business, still in the heyday of the open range, had been booming, and successful early investments by the English and Scots were still motivating other moneyed British to seek opportunities in the American West.

Though Lawson’s report had been favorable, prospective investors were hesitant. After many offers and counter-offers, the Swan Land and Cattle Company Ltd. was registered in Scotland on March 30, 1883. The capitalization was between $2.6 and $2.9 million, about $60 and $67 million in today’s dollars. Alex Swan was named manager at a salary of $10,000 per year, or approximately $231,400 in today’s money, with the freedom to spend some of his time on other ventures.

The company purchased two lots in Cheyenne, for a headquarters and stable. With the consent of board Chairman Colin MacKenzie, Swan also arranged for about 52 miles of telephone lines to connect the Cheyenne headquarters with Hi Kelly’s, the headquarters ranch on Chugwater Creek, and other Swan Company ranches. The installation cost about $4,850—about $112,000 in today’s dollars—plus approximately $184, or about $4,257 in today’s dollars, in annual rent on the telephones.

More land and ranches

In its first year, the company purchased six ranches along the Chugwater and nearby Richard and Sybille creeks for their waterfronts and hay meadows. This gave them uninterrupted control of large portions of land along the three creeks, and the legal right to take down the fences that had separated these individual holdings. Swan also filed for the company on the square-mile sections of checkerboarded land along the Union Pacific railroad, purchasing Union Pacific lands and the alternate government sections among them; and leasing railroad lands where the Union Pacific refused to sell them.

Trouble with the board

For the years 1883 and 1884, the company paid its shareholders a dividend of 9 and 10 percent respectively. Thus, during its first two years, the Swan company outperformed almost all the other major cattle companies.

In 1884, the average price per head was $40.67; in 1885, it sank to $33.80. The 1885 dividend was 6 percent. In 1886, prices fell again, to $26.34 per head, and the company paid no dividend.

The shareholders were unhappy with the board of directors, and the board in turn had become dissatisfied with Swan and his management. A chronic sore point was the original herd count.

At the time, on all the huge ranches in Wyoming Territory, because the cattle ranged over such a large area and were not fenced long enough to be counted, no accurate count was attempted. Managers were supposed to keep records of each year’s number of calves branded and animals sold. Estimated losses from storms and predators were deducted from the total on the books or, if death losses were not deducted, sellers gave buyers a discount off book totals.

This was “book count,” widely accepted in the early days of the cattle industry as the only practical way to keep track of large herds. By nature, book count was subject to major errors and, for the dishonest seller, was an opportunity to exaggerate numbers.

Board members had been grumbling about Swan’s counts ever since they’d acquired the holdings of his three corporations. They suspected fraud, but could only speculate about it, and about the likelihood of careless management. Although Swan maintained the individual ranches in good condition and staffed them with competent men, even his most loyal employees agreed that his record-keeping was sloppy and secretive.

The winter of 1886-87

Historians have estimated that 15 percent of Wyoming cattle died during the severe winter of 1886-87. Losses fell heavily on the Swan Land and Cattle Company, with Rufus Rhodes, a foreman, estimating a loss of 25 percent or more. During the same period, Alexander Swan’s personal financial empire began to totter.

Historians disagree about what brought him down. Historian Helena Huntington Smith attributed his fall to a single catalyst, an unpaid $25,000 note of Thomas Drimmie, held by the German Savings Bank of Davenport, Iowa, which Swan had signed for security. This was a favor he often did for friends and associates.

Drimmie, a Scot, had settled in Iowa and was a major Swan Company shareholder. Early in 1887, when Drimmie defaulted on his note, the bank turned to Swan for collection. This was apparently the beginning of his failure to pay many other obligations. The landslide was unstoppable.

Historian Lawrence Woods, while noting Drimmie’s possible role in Swan’s collapse, suggests that the real culprit was probably Swan’s large, unwise speculation in the Carbonate Belle Lode of the Silver Crown mining district about 20 miles northwest of Cheyenne. Swan habitually borrowed from existing enterprises to finance newer ones, and became a shareholder in the Cheyenne Mining and Reduction Company, capitalized at $1 million, or nearly $25 million in today’s dollars, probably sometime in 1886. The mines did not produce the hoped-for significant amounts of either gold or copper, but many investors, including Swan, had paid substantial sums for exploration and development before the futility of these efforts was clear.

In May 1887, the board of directors dismissed Swan as manager. About two months later, the company sued Swan and all the other original vendors—the partners who had sold the company its original assets—in an attempt to recover costs from exaggerated herd counts. This suit eventually failed on procedural grounds.

In 1888, Swan moved to Ogden, Utah, where he died on Aug. 9, 1905. He left no record of his side of his conflicts with the board.

Finlay Dun

The board named a temporary manager—Finlay Dun, a Scot and one of their own members. A story has survived that shows the difficulties a corporation can have when attempting to run a faraway business about which many of its directors know little.

Dun traveled to the U.S., charged with getting an accurate count of the cattle. He tried to do so, at roundup time, and wherever he encountered cattle on the range. To keep track of which cattle had been counted, he marked them with blue paint. The paint wore off or washed off, an outcome that even the least experienced cowboy on any of the ranches could have predicted and probably did.

Dun also had to verify the company’s many land titles, and discovered that titles to about 17,000 acres were not clear. Many of these were desert entries on which Swan’s friends had filed, almost certainly with an unwritten agreement to turn their ownership over to Swan after proving up—a common practice at the time. Many of these people were now reluctant to sign their titles over to the company.

John Clay Jr.

In 1888, the board appointed John Clay Jr. as manager. Clay, also a Scot, had business dealings in Canada and the United States in the 1870s and finally emigrated in 1882. He lived in Chicago and went into the livestock commission business, eventually owning a large livestock commission house, Clay, Robinson, and Company. He also managed several Wyoming cattle ranches.

The son of a Scottish farmer, Clay apparently disliked Swan, who during his years of prosperity had acquired the bearing of a patrician along with his wealth.

Clay’s annual salary was $7,500, or nearly $187,000 in today’s dollars, and the board stipulated that he had to spend five months per year in Wyoming. At the time of Clay’s appointment, the board did not discuss which commission house should handle Swan Company livestock sales; Clay, Robinson and Company ended up doing so, collecting all the commissions on these sales.

This may be an example of how well Clay looked after his own interests. He also protected his reputation and demonstrated his ability to walk both sides of a fence, as Wyoming events from 1891-92 show.

Clay was elected president of the Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association in 1891. This was the year planning began for the “lynching bee” that was supposed to rid Johnson County, Wyoming of cattle rustlers. In his memoirs, Clay claims that in 1891 he told Frank Wolcott, one of the main instigators, to “count me out,” and that he forgot all about Wolcott’s plan. In April 1892, when prominent members of the Association attempted their invasion of Johnson County, Clay was in Scotland, and had been for most of that winter. “I was innocent as an unborn babe” of planning and instigating the raid, Clay insisted decades later.

He hastened back to Wyoming to see to the legal defense of his cronies and in his memoirs refers to the invaders as a “brave band … able, active men, intelligent beyond the average.” He also defends the lynching of presumed rustlers, including James Averell and Ella Watson, the so-called Cattle Kate.

One of Clay’s first acts as manager of the Swan Company was to cut costs. He closed the company’s office in Cheyenne, moving the official headquarters to Chugwater, nearer to most of the ranch activity.

“After going over the different ranches carefully, … [the company] seemed to be running full steam in spending money and eating grub,” Clay wrote. “They had seven cooks with helpers at two places, nine men in all, at about $40 a month all found. They had to have a general headquarters, a farming ditto, a cattle ditto, then one foreman did not care to live with another, and so on.” Clay reduced the cooking staff to one, and rented out many of the ranches. “These violent changes made a manager unpopular,” Clay commented.

Clay dismissed

Members of the board and shareholders began to complain that Clay did not spend the stipulated five months in Wyoming, refused to accept significant cuts in his own salary and was opposed to the paying of dividends until the company was on a more sound financial footing. Some also objected to Clay’s practice of handling all land and livestock sales through Clay, Robinson and Company.

In 1896, the board replaced Clay with Alexander Bowie, foreman at the Chugwater ranch. Clay blamed his dismissal in part on his own policy “to guide the company solely on my own judgment so far as the physical management on this side [of the Atlantic] was concerned, and then tell the home board what I had done.”

In 1904, after years of declining cattle markets and losses from hard winters and summer droughts, the company purchased 15,000 head of sheep. One longtime employee, General Superintendent Edward Banks, refused to work with sheep, and quit. The last year of joint cattle and sheep operation was 1910. Although much of the range was still open, it was crowded, and ranchers large and small, the Swan Company included, had learned to raise feed to winter over their cattle. Therefore, the company’s feed bills and pasture rental were climbing.

Clay returns

In 1912, Clay returned to the company, joined the board and appointed a Wyoming manager, Curtis Templin. In the fall of that year, Clay and James T. Craig, an outstanding Wyoming stockman and longtime associate of Clay’s, formed the company’s executive board in charge of American operations. The directors agreed to this “reluctantly,” because, sources imply, Clay insisted.

For the next decade and a half, the company cut more costs and struggled with the loss of access to public lands. The board disputed with Clay about whether to sell sheep, and then sold some of its land and sheep and enjoyed a degree of temporary prosperity from World War I inflation.

The American Swan Company

In the agricultural depression after World War I, the company could not hope to sell any of its land. Lamb and wool prices fell. In 1922, Clay reported that he had cut operating expenses nearly in half, mostly by reducing salaries.

Double taxation was a major problem. Members of the board had to pay British and American income taxes, both corporate and personal. Tax law defined residence by a company’s location of control and responsibility.

The board transferred all of its affairs to an American board, concluding business on Dec. 31, 1925. Total assets were about $1 million, or nearly $14 million in today’s dollars. Slightly less than half were land and improvements, about one-fourth was livestock; the balance was investments and savings. The new company was organized in corporation-friendly Delaware on Feb. 15, 1926, as the Swan Company of Delaware.

The company after Clay’s death

After Clay died on March 17, 1934, management continued under Templin at the Chugwater headquarters. Although the company had some good years despite drought and depression during the 1930s, its goal was to sell all its assets. This was an acknowledgment that large profits from sheep and cattle—or sometimes any profits at all—were impossible. The land remained unsaleable until about 1943, during World War II when values and sales picked up. By Dec. 20, 1951, the company was dissolved.

The financial saga of the Swan Land and Cattle Company Ltd. is a series of intricate corporate restructurings and different forms of financing. These events reveal an ongoing scramble to float the directors’ belated investments in a boom nearly over, and include the slow dawning of truth—that cattle would never again yield large returns—combined with severe weather, long-distance attempts at management and changes in land use and laws.

One term recurs through all the financial language: debenture. A debenture is a bond not backed by a specific lien on particular assets, but only by the general credit of the issuer. Apparently, the company often resorted to debentures because they were more liquid than other instruments.

It was a rocky path, especially for the ordinary shareholder, with gullies to fall into and bitter financial winds to endure, just as the company’s uncounted items of flesh-and-blood inventory did over so many acres and years on the Wyoming range.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Clay, John. My Life on the Range. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962, 193-222, 261-277.

- London Times, March 20, 23, 24, 1883. Gale Newsvault. Accessed Aug. 3, Aug. 8, 2017, at www.find.galegroup.com.

- Wyoming Newspapers. Accessed Aug. 2, 2017, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov:

The Carbon County Journal, Sept. 27, 1884, Jan. 3, 1885.

Cheyenne Daily Leader, Nov. 13, 1877.

Secondary Sources

- “1882 Dollars in 2017.” Accessed Sept. 13, 2017, at http://www.in2013dollars.com/1882-dollars-in-2017.

- “1883 Dollars in 2017.” Accessed Sept. 1, 2017, at http://www.in2013dollars.com/1883-dollars-in-2017?amount=18950000.

- “1886 Dollars in 2017.” Accessed Sept. 13, 2017, at http://www.in2013dollars.com/1886-dollars-in-2017.

- “1888 Dollars in 2017.” Accessed Sept. 13, 2017, at http://www.in2013dollars.com/1888-dollars-in-2017.

- “1925 Dollars in 2017.” Accessed Sept. 13, 2017, at http://www.in2013dollars.com/1925-dollars-in-2017.

- Gillespie, A. S. “Bud.” “Reminiscences of a Swan Company Cowboy.” Annals of Wyoming, 36:2, October 1964, 199-203. Accessed July 26, 2017, at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom36121964wyom.

- Herman, Marguerite. “Laramie County, Wyoming.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed Sept. 4, 2017, at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/laramie-county-wyoming.

- Mothershead, Harmon Ross. The Swan Land and Cattle Company, Ltd. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

- Smith, Helena Huntington. “The Rise and Fall of Alec Swan.” The American West, 4:3, August 1967, 21-24, 66-68.

- Western, Samuel. “The Wyoming Cattle Boom, 1868-1886.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed July 24, 2017, at /encyclopedia/wyoming-cattle-boom-1868-1886.

- Woods, Lawrence M. Alex Swan and the Swan Companies. Norman, Okla.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2006.

Illustrations

- The map of the Swan holdings is from The Swan Land and Cattle Company, Ltd., by Harmon Mothershead, published in 1971 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Used with thanks and permission from the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla.

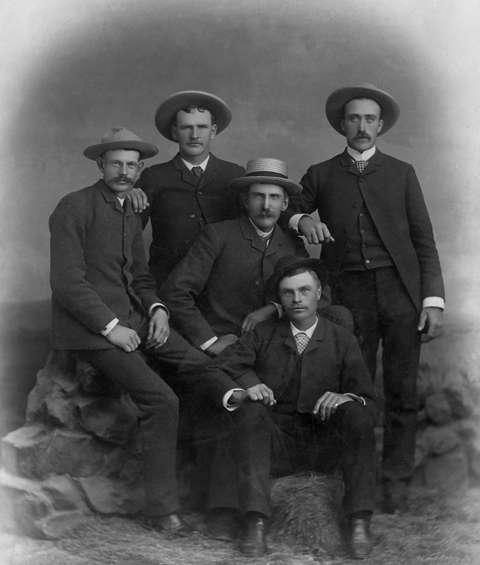

- The rest of the photos are from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks. Archive records contain only four names for the 1900 photo of five ranch managers; we have taken our best guess at which is which, based on other photos of some of the men. Two of the other men are George Prentice and Duncan Grant. Anyone with more information is urged to contact editor@wyohistory.org.