- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Muries: Wilderness Leaders In Wyoming

The Muries: Wilderness Leaders in Wyoming

From their modest upbringings, Mardy and Olaus Murie became diligent, adventurous and charismatic leaders of the American conservation movement. With their siblings, Louise and Adolph Murie, they shaped conservation biology and ecology and are credited with some of our country’s most historic efforts to protect wild lands. The two couples split their time between remote Alaska and a ranch at the feet of the Tetons, where the Murie Center carries on their efforts today.

Mardy was born Margaret Elizabeth Thomas in Seattle, Wash., on Aug. 18, 1902, to Minnie Eva Fraser and Ashton Wayne Thomas. Shortly after her birth, the family, including Mardy's older half brother Franklin, moved to Juneau, Alaska, where they lived for five years. Then Mardy's parents divorced, and she and her mother returned to Seattle. In 1910, Minnie married Louis Gillette, an attorney for the U.S. government. The following year, when Mardy was nine, the mother and daughter traveled by steamship and riverboat to meet him in Fairbanks. For the next decade they lived in a small log cabin on the edge of town.

Alaska

On March 16, 1912, Mardy’s half sister, Louise, was born in Fairbanks, followed by a half brother, Louis. Mardy’s childhood was shaped by the spirited, neighborly and difficult life of small-town Alaska. In Fairbanks, she learned to keep the wood stoves going in both rooms of the cabin, to hang laundry inside to dry in winter, and to keep her dog, Major, on a long leash so he could fight with other dogs at a safe distance as she walked through town.

When she was 15, Mardy traveled 400 miles with mail carriers by horse-drawn sleigh, cart and dogsled from Fairbanks south to the Alaskan coast to visit her father. The journey was the last of its kind before the railroad reached Fairbanks. Mardy made friends along the trail and was not afraid, even as the drivers probed river ice for thin spots and the horses swam through open water while she perched on the floating mail wagon.

A blue-eyed biologist

Starting age 18, Mardy went to Reed College in Portland, Ore., for two years, coming home to Fairbanks for the summers. In Fairbanks during the summer of 1921, she met a tall biologist with bright blue eyes. His name was Olaus Murie, and he was about to start off by dogsled for the Brooks Range in northern Alaska to study caribou for the U.S. Biological Survey.

Olaus Johan Murie had been born March 1, 1889, in Moorhead, Minn., to Joachim and Marie Murie, who had recently immigrated from Norway. They had another son, Martin, a few years later. When Olaus was seven his father died. Marie married a Swedish immigrant named Ed Wickstrom, and they had a son named Adolph. Ed passed away just two years later. Marie took back the Murie name and raised the three boys on her own.

Olaus attended Fargo College in North Dakota and Pacific University in Oregon, earning his degree as a biologist in 1912. He worked as a collector for the Carnegie Museum and served in the U.S. Army in World War I before taking a position with the U.S. Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) in Alaska.

Olaus planned to have his brother Martin assist him on the caribou study of the Brooks Range the year he met Mardy, but Martin died of tuberculosis that year, and Olaus invited his half brother, Adolph. Meanwhile, Mardy transferred to Simmons College in Boston to live with her father who was working there for the winter.

She took the next year off from college, living in Fairbanks and exchanging letters with Olaus while he and his brother explored the Koyukuk River Valley between the Brooks Range and the Yukon River by dogsled to survey caribou. That summer, Mardy and her mother visited Olaus and Adolph at a research camp near Mount McKinley (now Denali), and Mardy and Olaus agreed to marry.

For her last year of college, Mardy transferred to the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, now the University of Alaska, in Fairbanks. She lived with her family and continued to correspond with Olaus in Washington, D.C. In the spring of 1924, Mardy earned her business degree, the first woman graduate of the college. Olaus was in the Arctic surveying waterfowl and other species.

A wedding on the Yukon

After five months apart with only limited correspondence to connect them, Mardy traveled 800 miles down the Yukon River to meet her groom in Anvik. Her mother and a bridesmaid made the journey with her. Mardy and Olaus married at 3 a.m. on Aug. 19, 1924, in a small candlelit chapel near the banks of the Yukon. The baker on the steamship made a surprise wedding cake topped by a tiny log cabin with frosting snow dripping off the eaves.

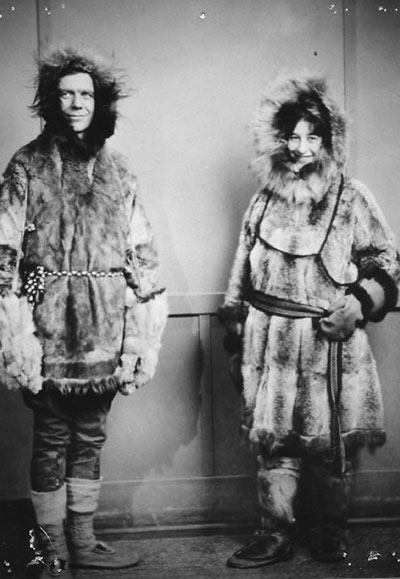

The couple packed fur parkas and boots and set off to honeymoon in central Alaska for three months. They traveled by boat up the Koyukuk River and by dogsled into the Endicott Mountains and south to the Yukon River while Olaus collected specimens. They spent the rest of the winter in Washington, D.C. In the spring Olaus went back to Alaska to study grizzlies and Mardy lived with her mother and stepfather in Twisp, Wash., where she gave birth to a son, Martin.

The following autumn the couple returned to Washington, D.C., and in spring they packed up the baby and traveled with their friend, Jess, to the Old Crow River in northeast Alaska. This was a difficult trip: relentless mosquitoes, a broken motor on the boat and not much success with the research. Mardy kept busy taking care of the baby, cooking, learning about Olaus’s scientific work and washing diapers in old gasoline cans. After the motor broke, the men poled and lined the boat upriver. Jess “had a very nice high tenor voice,” Mardy wrote. “I love to sing, too. We both knew hundreds of songs, and I really believe this saved our sanity, our friendship, and the success of the expedition.”

Wyoming

In 1927, Olaus and Adolph both earned graduate degrees from the University of Michigan. In Twisp, Mardy gave birth to a girl named Joanne. Olaus was sent to Jackson, Wyo., to study elk. Mardy moved there in mid-July.

In Wyoming, she continued to join Olaus in his field camps, cooking and taking care of the children who slept in tents and learned about the mountain animals and plants. In 1930, Olaus and Mardy built a house on the edge of Jackson where their third child, Donald, was born.

Meanwhile, Mardy’s sister, Louise or “Weezy,” had fallen in love with Olaus’s brother Adolph. They married in 1932 and joined their siblings in Jackson.

Adolph had earned a Ph.D. in the new field of ecology from the University of Michigan. He worked for the National Park Service, and the couple spent 25 summers in McKinley National Park where Adolph studied wolves, grizzlies and other species. He also wrote a book about coyote ecology in Yellowstone and promoted the idea that managers must protect entire ecosystems including predators rather than manage for individual species.

Louise earned a degree in botany from the University of Michigan. In addition to raising their son, Jan, and daughter, Gail, in McKinley National Park, she compiled an extensive catalog of the park’s vegetation, but it was not published.

Conservation politics from a ranch near Moose

In 1945, with Olaus’s elk study finished and son Martin fighting in World War II, Mardy, Olaus, Louise and Adolph bought the STS Ranch, a 77-acre dude ranch near Moose, Wyo. Two years earlier, President Franklin Roosevelt had signed an executive order creating Jackson Hole National Monument, the precursor to Grand Teton National Park, which bordered the ranch.

Also in 1945, Olaus retired from the U.S. Biological Survey and took on part-time directorship of the Wilderness Society, an organization that he had helped form ten years earlier. Moose, Wyo., became the headquarters for the organization.

The family also travelled. In 1948, Olaus won a Fulbright grant to study elk that Teddy Roosevelt had sent to New Zealand from North America. Donald, 17 years old, was the expedition photographer. In 1956, Olaus and Mardy flew to the Sheenjek River Valley in northeast Alaska with three young biologists—Bob Krear, George Schaller and Brina Kessel—to seek out areas with wilderness value. That summer expedition was one of the most delightful times in Mardy and Olaus’s lives together. In 1958, Mardy and Olaus sailed to Norway, Finland, England and back to New York, dancing and partying each night on the ship. In 1961, they returned to the Sheenjek River for three weeks.

Olaus was an accomplished artist, illustrating his field notebooks with detailed portrayals of wildlife he encountered in his studies. He authored many scientific articles, reports and books including Food Habits of the Coyote in Jackson Hole, Wyoming (1935), The Elk of North America (1951), the Peterson Field Guide to Animal Tracks (1954) and Journeys to the Far North (1973). He was granted an honorary doctorate from Pacific University in 1949. He was internationally admired as a charismatic speaker and a respected biologist.

From its headquarters at the Murie Ranch, The Wilderness Society pushed for extensive conservation measures throughout the late 1940s and 1950s. In 1956, Olaus, with sponsorship from the Wilderness Society and other conservation groups, led an expedition to the Brooks Range. Wilderness preservation of the area was partially realized in 1960 when Interior Secretary Fred Seaton established the Arctic National Wildlife Range, now known as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Olaus spent the winter in 1962 with Howard Zahniser, a member of the Wilderness Society who was working to pass a Wilderness Act. The Wilderness Society’s 1963 meeting was held at Camp Denali in Alaska with Adolph and Louise also attending.

That October, Olaus, who had required surgeries over the years to remove skin cancer, was admitted to the hospital in Jackson. Three days later, Oct. 21, 1963, he passed away at the age of 74.

Continuing alone

Mardy spent the winter with her mother. She had served as Olaus’s wife, secretary and assistant for the 39 years of their marriage. Family and friends encouraged her to find a new calling, but she cared about and understood the fight for wilderness protection and decided to continue the work. The following autumn, President Lyndon B. Johnson invited Mardy and Howard Zahniser’s widow, Alice, to the White House where he signed the Wilderness Act.

As her confidence as a wilderness advocate grew, invitations for her involvement did, too. Mardy was repeatedly asked to write introductions to books and to give talks. She wrote her own speeches as well as countless letters to politicians, managers and other decision makers, and she personally answered all the letters she received. She authored Two in the Far North (1957), Wapiti Wilderness with Olaus (1966), and Island Between (1977).

When she wasn’t hosting family, friends and fans at the Murie Ranch, Mardy adventured. In 1965, she and her wealthy friend Elise Untermeyer explored conservation sites and talked to biologists in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Egypt for five weeks. In 1967, Mardy and friend Mildred Capron, a filmmaker, drove 10,000 miles in a camper van and traveled by boat and plane to make a film about Alaska. Mildred lived at the Murie Ranch until her death ten years later. In 1969, Mardy returned to New Zealand and Australia to visit friends of 20 years before.

Mardy, Adolph, and Louise sold their ranch to the National Park Service in 1968 to be incorporated into Grand Teton National Park, and the family maintained a long-term lease on the property. Mardy began to work with the newly founded Teton Science Schools, inviting students to the ranch and sharing her thoughts on wilderness conservation.

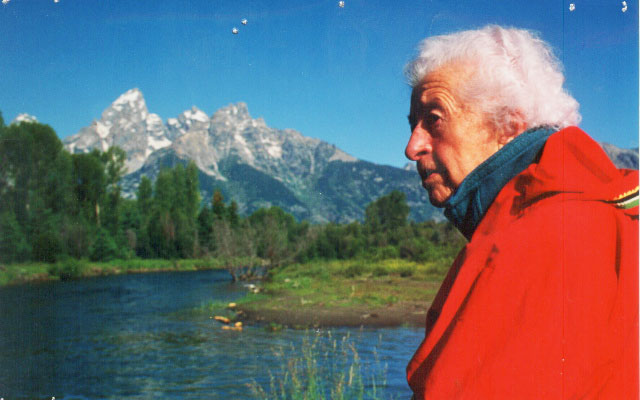

In 1975, she spoke at a National Park Service conference, and then spent much of the year flying around Alaska as a consultant identifying lands that merited protection. Her years of experience traveling Alaska and learning its biology and ecology from her husband informed her report, which was used by Congress to ultimately pass the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in 1980, which protected 56.4 million acres as wilderness in addition to tens of millions acres more as national parks and wildlife refuges.

Adolph Murie passed away in 1974 at the age of 74. Louise moved from the Murie Ranch to live in Jackson and later married a physician named Donald MacLeod.

Honors and awards

In 1976, Mardy received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. In the 1980s, she received the Audubon Medal, the Sierra Club’s John Muir Award and the Wilderness Society’s Bob Marshall Award in addition to honorary doctorates from Trinity College and the University of Wyoming and many other honors. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of her contributions to wilderness conservation.

In 1997, with Mardy and Louise’s approval, the Murie Center was established at the Murie Ranch to carry on the work and ideals of the Murie family. Mardy passed away at her home in Moose on Oct. 19, 2003, at the age of 101. Louise died in Jackson May 22, 2012, at age 100.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Murie, Margaret. Two in the Far North. Anchorage: Alaska Northwest Publishing Company, 1957.

- Murie, Margaret and Olaus. Wapiti Wilderness. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966.

- Murie, Olaus. Journeys to the Far North. Palo Alto, Calif.: The Wilderness Society and American West Publishing Company, 1973.

- __________ The Peterson Field Guide Series: A Field Guide to Animal Tracks. Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1954.

Secondary Sources

- American Academy for Park and Recreation Administration. “Olaus Johan Murie: Cornelius Amory Pugsley Local Medal Award, 1953.” Accessed Jan. 21, 2014, at: http://www.aapra.org/Pugsley/MurieOlaus.html.

- Craighead, Charles and Bonnie Kreps. Arctic Dance: The Mardy Murie Story. Portland, Ore.: Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company, 2002.

- Love, Johanna. “Murie clan botanist MacLeod dies at 100.” Jackson Hole News and Guide, May 23, 2012. Accessed Jan. 21, 2014, at: http://www.jhnewsandguide.com/news/environmental/murie-clan-botanist-macleod-dies-at/article_36a55cc3-b39e-556f-a916-49a1b7f2ea2a.html.

- The Murie Center. “The Murie Legacy.” Accessed Jan. 21, 2014, at: http://www.muriecenter.org/the-murie-legacy.

- Wilderness.net. “Olaus and Mardy Murie: Alaska's Passionate Protectors.” Accessed Jan. 21, 2014, at: http://www.wilderness.net/NWPS/murie.

For Further Reading

Duerr, Steve. “Murie Legacy Still Going Strong 50 Years Later.” Jackson Hole News & Guide, Oct. 30, 2013. Accessed Feb. 27, 2014 at http://www.jhnewsandguide.com/opinion/guest_shot/murie-legacy-going-strong-years-later/article_92ca6d9a-5767-5db2-9a67-5f7ad1be8daf.html. Article by a former director of the Murie Center on the 50th anniversary of the death of Olaus Murie, with more details on the Muries’ conservation achievements and awards.

Illustrations

- All photos are from collections at The Murie Center, with permission and special thanks to Murie Center Archivist Anna Barker.

- Our birding friends disagree about the species Olaus is holding in the black-and-white photo in the photo gallery. We have votes for both gray jay, or camp robber, and Clark’s nutcracker. Comments on this question are welcome at editor@wyohistory.org.