- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Teton County, Wyoming

Teton County, Wyoming

Teton County is located in the northwest corner of Wyoming. The federal government owns 97 percent of the land, including two national parks--Yellowstone and Grand Teton. The region is mountainous and geologically active; there are numerous small earthquakes, most of which are not felt by residents.

The best-known natural wonders in the county are the thermal, scenic and wildlife features of Yellowstone Park, established in 1872, and the mountains of the Teton Range, the county’s namesake. Those striking peaks were created fewer than 10 million years ago—recently, in geological terms—by great pressure of blocks of rock on opposite sides of the Teton fault line pushing against each other.

Teton County’s human history can be geographically divided, similarly, into two sections: Yellowstone and Jackson Hole, which includes Grand Teton National Park. (Around 40 percent of Yellowstone National Park lies in Teton County; the rest is in Park County.) The history of Yellowstone is the stuff of western legend, as it was used and sometimes occupied by all sorts of people from paleo-Indians to trappers and explorers.

The history of the Jackson Hole area, on the other hand, does not include the exploits of many other places in Wyoming, which had mining, railroads, the Pony Express and infamous outlaws in their storied past. In Jackson Hole, the main population center of Teton County, homestead settlement did not begin until the 1880s when the first few claims were filed.

Prior to that, American Indians were the only regular inhabitants of the valley. Even fur trappers and explorers did not frequent the area in great numbers because of the difficult terrain. The Indians, though, had used the land for thousands of years. Their familiarity with the trails and seasonal changes made entrance and exit easier for them.

Early Inhabitants

Archeological evidence shows that the human history of the area dates back as far as 11,000 years ago. A number of projecting points, pots and roasting pits have been found, but a great deal is still unknown about the people who used them. Probably they moved through Jackson Hole when seasons and food sources allowed. Recently discovered evidence suggests that paleo-Indians sometimes wintered in the valley—a likelihood doubted for many years because of Jackson Hole’s harsh climate.

Descendants of the early peoples still occupied the valley when the first European and American explorers and fur trappers arrived in the early 1800s.

Early exploration and settlement

Differing names and descriptions of places make it hard to say which trapping or survey parties might actually have entered Jackson Hole. For a long time it was thought that John Colter was the first Euro-American to visit the valley after he left the returning Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806, but careful review of his routes casts doubt on this attribution.

During the peak years of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, 1825-1840, none of the annual rendezvous trade fairs were held in Jackson Hole, though many were held along the upper Green River a short way to the south, and mountain men trapped in Jackson Hole or passed through it. Regardless of whether they came into the valley, the Teton Range was a primary landmark by which travelers oriented themselves. David E. Jackson, for whom Jackson Hole is named, frequented the valley in the 1820s as the owner of a fur trade company.

Little Euro-American activity occurred in the valley between 1840 and 1860.

A military expedition led by Captain V.F. Raynolds came through Jackson Hole in 1860 on the way to survey the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Raynolds declared the area unfit for a railroad but this first documentation of the valley would set the basis for future government surveys.

The most famous of the expeditions to explore the area was led by Ferdinand Hayden of the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. Hayden, a geologist, physician and veteran of the Raynolds, was accompanied this time by painter Thomas Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson. Their pictures, plus Hayden’s reports, helped make the case for establishing Yellowstone Park in 1872.

Prospectors like Walter DeLacy investigated Jackson Hole in the 1870s but none were successful with mining.

Army expeditions led by William Jones and Gustavus Doane in 1873 and 1876, respectively, made few lasting contributions. The Doane party, which traveled up the Yellowstone River from Montana, was lucky to survive. Poor preparation led to disaster after disaster in Yellowstone and Jackson Hole, until finally the troops made their way to Fort Hall, in eastern Idaho in early 1877.

By the mid-1880s Jackson Hole’s spectacular scenery and abundant wildlife were drawing sport hunters. Owen Wister first came in 1885, and returned for many hunting trips thereafter. Jackson Hole provides one of the many Wyoming settings in The Virginian, his million-selling novel published in 1902.

The 1880s were also the era of the first homestead claims, much later than most places in Wyoming. Single men were among the first settlers but single women and couples also homesteaded. These early settlers offered meals, lodging and outfitting services to early tourists. Families arrived slightly later, including Mormons seeking the freedom to practice their religion and customs that mountain isolation offered them. People from a variety of backgrounds soon populated the valley.

Outlaws and vigilantes

Still, the place was extremely isolated, and also was gaining a reputation as a haven for outlaws and vigilantes. One outlaw was a horse thief known as Teton Jackson, said to have used the valley as a hideout for running stolen horses between Idaho and central Wyoming. Characters like these were generally accepted as long as there was peace.

This peace was interrupted at Deadman’s Bar on the Snake River in 1886, however, with the murder of three prospectors by their partner. The trial, in the county seat at Evanston, 200 miles to the south, ended with an acquittal, leading valley residents to distrust a distant legal system.

An 1893 incident at the Cunningham Cabin on Spread Creek in Jackson Hole was perhaps evidence that locals had decided to mete out justice instead of waiting for legal action. A shootout at the cabin led to the deaths of two men, later thought to be innocent. Locals had been riled up by men from Montana claiming that the two were horse thieves. The Montanans had claimed to be marshals but it was later recalled that no one had seen any credentials, and the incident became a shameful community secret.

The Race Horse Case

Distrust of outsiders might help to explain the tensions between white settlers and Indians tribes that led first to an armed skirmish over hunting rights in 1895, and eventually to a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision.

When the Eastern Shoshone and Bannock tribes agreed in 1868 to move onto new reservations, they retained the right to hunt off the reservations on unoccupied lands. The Shoshone were located on Wind River in Wyoming Territory, and the Bannock on a reservation at Fort Hall, on the Snake River in eastern Idaho Territory.

The two tribes are closely related. Over the next generation, a tradition grew up of regular visits and hunting trips between the two. Jackson Hole and its populous elk herds were about halfway between.

By the 1880s, the few white settlers who had trickled into Jackson Hole made their living by subsistence hunting and trapping, stock raising and perhaps rustling, and as hunting guides for customers—dudes, they were already beginning to be called—like Wister. None of these groups seem to have welcomed the Indian families that passed through to hunt and visit each year.

Soon after Wyoming became a state in 1890, the Legislature passed game laws limiting hunting to the fall months and limiting the number of animals that could be killed. Jackson Hole was still part of Uinta County, with its county seat at Evanston, and local law enforcement was scarce. In early summer 1895, valley settlers began seeking help enforcing the game laws from federal, state and eventually county officials, but got little response.

A local constable formed a posse, and matters came to a head in a confrontation with a Bannock band. Shots were fired, one Bannock died, another was wounded and a child disappeared in the skirmish. The rest of the Indians fled. Newspapers quickly sensationalized the story. Word that all whites in Jackson Hole had been killed by Indians screamed from headlines as far away as New York.

The Bannock leader Race Horse was charged with seven counts of killing elk out of season as a test case so that a precedent regarding hunting rights could be set. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1896 that the state game laws had superseded the Indians’ treaty rights, and that the land in question was in any case no longer unoccupied. It was a landmark decision in questions of Indian sovereignty that remain in dispute today.

Creation of Teton County

Because of the isolation, only a few settlements and ranches were located in Jackson Hole before 1900.

The communities of Moran at the north end of the valley, Kelly and Jackson near the middle, and Wilson on the western edge at the base of Teton Pass became social centers with post offices and stores, though Wilson never offered much more than basic necessities. From Wilson, however, a road led over the pass to Idaho, where there was a rail connection. Most goods were shipped into the valley by that route.

Alta, in Wyoming but on the west side of the Tetons, was more accessible through Idaho. Other communities like Bondurant and Alpine developed to the south, primary entry points into Jackson Hole, though neither is in Teton County today.

All of these communities were initially part of Uinta County. The county seat in Evanston was 200 miles south, and the distance made it difficult for Jackson Hole residents to conduct business with the county and take care of legal matters.

Lincoln County was formed in 1911 out of the northern stretches of Uinta County and parts of Sublette and Sweetwater counties but Kemmerer, the county seat, was still quite far from Jackson Hole. Finally, in 1921, the northern section of Lincoln County became Teton County, even though the population and land valuation didn’t meet the minimum requirements under state law. A new law was passed to allow for the unique “geographical conditions” since it would otherwise have been a long time before the County would be able to meet the state requirements.

Image

Kelly and Jackson, incorporated in 1914, vied for county seat, and Jackson eventually won in a hotly contested county-wide vote. Jackson also had recently attracted national attention when, in the great tradition of Wyoming equality, it had elected Mayor Grace Miller and an entirely female town council, in 1920. The new town government also appointed several women to key positions, even a town marshal.

In 1927, part of a mountain slid away, damming the Gros Ventre River above Kelly behind the pile of earth made by the landslide. When the dam broke two years later, most of Kelly was destroyed by the flood. Today, Jackson is the largest and only incorporated town in Teton County.

Legacy of Conservation

By the early 1900s, meanwhile, people in the area developed a unique relationship with elk. In addition to good livelihoods for hunters and guides, the elk provided food for many local residents. As towns and population grew, the elk became even more important.

A series of bad winters caused massive elk starvation. Faced with elk dying in their yards and streets, residents asked for government help. Photographer and guide Stephen Leek documented the plight of the elk with images and pictures. He displayed them in various places around the country to gain support for the cause.

Image

These efforts led to creation of the National Elk Refuge, land permanently set aside for the elk by the federal government in 1912. A feeding program kept the elk from eating the hay grown by local ranchers and ensured that a hard winter wouldn't again lead to starvation. The feeding program, an early attempt to improve game management, is controversial today; critics argue that feeding the herd weakens it over time, as the system allows no natural selection for the healthier animals over diseased ones.

The local Boy Scouts also collect elk antlers from the refuge every spring and 80 percent of the proceeds from their sale are donated to this feeding program.

So it was that locals had already started a tradition of conservation when a proposal first surfaced in 1919 to create a national park in Jackson Hole. Grand Teton National Park was first established in 1929, and finally expanded to its present size in 1950, after 30 years of local controversy and spurts of national celebrity. Many locals feared the expansion of federal power in the valley that the park would bring. But it also brought millions of tourists. By the 1960s high-profile opponents, like Teton County Commissioner and later U.S. Senator Cliff Hansen, had publicly changed their minds on the question.

Economics

Eventually lands like the Elk Refuge and the national park became the valley's best assets, though the first economic activities to mature in the valley were agricultural. Early prospecting and mining ventures had failed to produce riches. With short growing seasons and difficulties raising cattle, early settlers also found creative ways to meet the needs of occasional travelers who ventured south from Yellowstone. As early as the 1880s and 1890s, local settlers guided sport hunters to game. Locals with the means to do so began to open their homes to offer accommodations for travelers.

As the popularity of the American cowboy grew in the culture of the United States, some cattle ranching operations boosted their income by offering dudes from the East a taste of the West. Later, some ranches were created solely to cater to dudes. On these places, livestock was on the scene mostly to enhance the ambience.

By the 1930s, Teton County was still an isolated place, but it was beginning to cater to a small, wealthy clientele. Growth remained limited, however, and not until after World War II did a combination of factors really begin to open up the Jackson Hole to tourists. The first of these was construction of an airport; the first commercial flights arrived in 1946. Second was expansion of the park to its present size in 1950, catering largely to summer tourists.

Third was the ski business.

The first local ski area, Snow King, had opened in Jackson in 1939 with a rope tow that allowed skiers to ascend to the top of the hill. One study made special mention of approximately 360 ski tourists in 1958 who were part of this burgeoning market. Though the study was not conducted annually, this might be the first census taken of skiers.

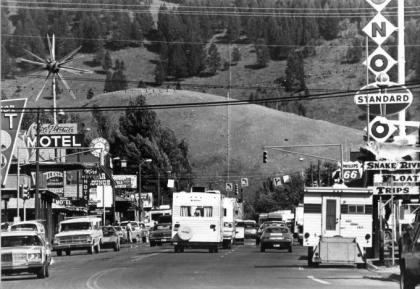

When the Jackson Hole Ski Resort opened in the mid-1960s, on national forest land above the new resort of Teton Village on the west side of the valley, Teton County residents discovered what would become the signature tourist draw during the winter. By the 1970s, tourism was paramount year round.

Jackson Hole today

Jackson Hole now ranks among the best-known resort communities in the West. Population has grown accordingly; between 1990 and 2000, Teton County’s population grew by 63 percent. Over the same years, population statewide increased by 9 percent.

Per capita income also has grown, and Teton County is one of the wealthiest counties in the nation. Most of that income does not come from wages, but from other sources. According to the Jackson Hole Almanac, between 1994 and 2003 wages provided just 40% of residents’ total income, on average. Income from investments and professional services are now the primary economic forces in the county. Tourism has dropped to second place.

Wealthy people are drawn to the county by its beauty and recreation opportunities, but also by the fact that Wyoming has no state income tax, and property tax rates are quite low compared to other upscale parts of the U.S.

Second homes dot the landscape, though infrequently occupied. At the same time, only 3 percent of the land in Teton County is in private hands—all the rest is public land. Demand for second homes, together with the limited land available for development led the median cost of a home in Teton County nearly to triple between 1990 and 2000.

The U.S. Census Bureau pegged the median value of a home in Teton County between 2007 and 2011 at $715,300. Wyoming’s home value was $181,900 for the same period— less than a fourth of the Teton County median value. Teton County has become an exclusive zip code.

Teton County’s high property values put the squeeze on middle-income people, however, forcing them to pay much higher property taxes or much higher rents than they would if those values were more in line with ones in other Wyoming counties.

All these factors, therefore, are connected to the high value people place on the public lands in Teton County. The public lands preserve the scenic vistas that so many come to see, and preserve space for the ongoing pursuit of fun. Thanks to those lands, people continue to visit—and many stay—to climb mountains, ski, camp, hunt, fish and boat.

But while longtime residents and newcomers alike appreciate how far Teton County has come since its creation, controversy remains about how to approach the future. Debate continues over how to preserve the county’s physical attractions, do a good job serving the millions of visitors, and at the same time maintain the character of a western community that has been so drastically changed by the influx of wealth from the outside.

Resources

- Associated Press, “Teton County No. 1 in country for wealth.” Casper Star-Tribune, April 18, 2004. Accessed Jan. 9, 2013 at http://trib.com/news/state-and-regional/teton-county-no-in-country-for-wealth/article_32fff743-b082-5cc9-9098-b83741123134.html.

- Betts, Robert B. Along the Ramparts of the Tetons. Boulder, Colo.: Colorado Associated University Press, 1978. p. 165, p. 168, p. 170-71.

- Burkes, Glen R. “History of Teton County (Part I).” Annals of Wyoming, 44:1, Spring 1972, 73-106. Accessed Jan. 9. 2013 at http://archive.org/stream/annalsofwyom44121972wyom#page/n0/mode/1up.

- Daugherty, John. A Place Called Jackson Hole. Moose, Wyo.: Grand Teton Natural History Association, 1999, chapters 2 and 4.

- Donahue, Jim, ed. Wyoming Blue Book: Guide to the County Archives of Wyoming, Cheyenne: Wyoming State Archives, 1991. Vol. V part I, pp. 730-737.

- Huidekoper, Virginia. “Origins of Teton County Government.” Manuscript, n.d. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum Archives, Collection no. 2002.0124.058.

- Jackson Hole Chamber of Commerce. A Study of the Resources, People and Economy of Teton County, Wyoming. By Floyd K. Harmston, Richard E. Lund and J. Richard Williams. Wyoming Natural Resource Board, 1959. p. 35-37, p. 69-70.

- “Jackson District Boy Scouts of America Elk Antler Auction,” Elkfest 2012. Accessed Jan. 9 2013 at http://elkfest.org/auction.htm.

- Schechter, Jonathan. “Entrepreneurs will set trails for growth” Jackson Hole News and Guide, July 25, 2012. Accessed Jan. 9. 2013 at http://w.jhnewsandguide.com/article.php?art_id=8817.

- Sustaining Jackson Hole 2005-2006: The Jackson Hole Almanac 2006; The Proceedings of the State of Our Community 2005. Jackson, Wyo.: The Charture Institute, 2005. pp. 15-28

- “State and County Quick Facts: Teton County, Wyoming.” U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed Jan. 9, 2013 at http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/56/56039.html.

- Teton County Board of Commissioners. The Problem of Teton County. By Philip H. Cornick and Robert H. Kirkwood. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum Archives, Collection no. 2002.0114.083. Jackson, Wyo.: 1954. P. 2-8

For further viewing

See a film by Jennifer Tennican, “The Stagecoach Bar: an American Crossroads,” for vivid insights into life in Jackson Hole since about 1950, centered on the always evolving scene at the Stagecoach Bar in Wilson. Copies available at the Teton County library.

Illustrations

- The photo of the Tetons from the Snake River Overlook is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

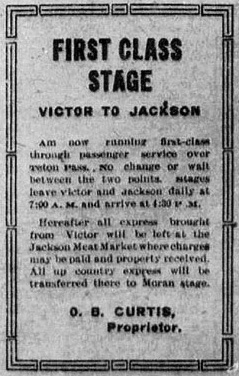

- The 1917 ad for stage service from Victor, Idaho to Jackson and the photo of the 1930s welcome sign are from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the Jackson Town Council, 1921, is also from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks. Left to right: Mae Deloney, Rose Crabtree, Mayor Grace Miller, Faustina Haight, and Genevieve Van Vleck.

- The photo of Fred and Eva Topping serving food to six dudes at the Moose Head Ranch, 1950s, is number 1958.0259.001 from the collections of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. The photo of a branding at the Moose Head Ranch, also 1950s, is number 1995.0340.018 in the collections of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. The photo of the ski race on Snow King is number 1958.1444.001 in the collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. The 1970s photo of traffic in downtown Jackson is number 2005.0006.005 in the collections of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. All used with permission and thanks.