- Home

- Encyclopedia

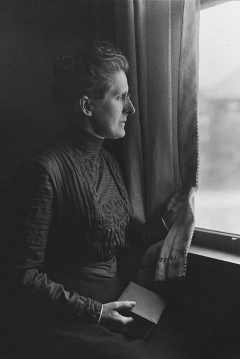

- Grace Raymond Hebard: Shaping Wyoming’s Past

Grace Raymond Hebard: Shaping Wyoming’s Past

The talented and ambitious Grace Raymond Hebard remained well known and respected as a historian throughout Wyoming during her lifetime. Though her books, articles and pamphlets contained the racism and stereotypes common in her era and were also criticized for historical inaccuracy and poor writing when they were published, Hebard soldiered on unfazed.

She also exerted a powerful influence at the University of Wyoming, where she was employed for more than 40 years, first as a paid secretary to and voting member on the board of trustees, and later as a professor of politics and history. Several of her books remain in print today, continuing Hebard’s influence on the history of Wyoming and the West—and continuing the controversy over the value of her work.

Not long after her death, a campus-wide memorial service was held Dec. 7, 1936 to honor her. Speakers heaped praise on Hebard. University President A.G. Crane described her as a prolific writer who “was a pioneer in discovering and preserving the early history of this region.” U.S. Senator Robert Carey told the audience that Hebard’s historical work was well done and “would remain as monument to her.”

Former Governor B.B. Brooks saw her as a “most accomplished author” and her literary work as “Wyoming’s best.” Her co-author of The Bozeman Trail, journalist, cowboy poet and Indian Wars historian E.A. Brininstool, said the late professor was “a most painstaking historian . . . never satisfied with anything but the truth and actual facts” in her historical research and writing. Others went on to describe Hebard as an “astute historian,” a “renowned scholar,” an “eminent authority” on Wyoming history.

Author Agnes Wright Spring—Wyoming state historian, director of the Federal Writers Project in Wyoming and, later, Colorado state historian—told those gathered in the auditorium that in her book on Sacajawea, Hebard “built an impregnable fortress of truths which will, I feel sure, withstand attack.”

Since that time, however, many scholars have come to believe that Hebard too often brought predrawn conclusions to her work, and then found so-called “facts” to fit them. Too often, the facts turn out to be more like fables when compared with stronger, contradictory source material, some of which was available to Hebard, and which she apparently ignored.

But she probably did not act out of any deliberate intention to deceive. Hebard was a strong-willed woman who gained significant power at a new institution—the University of Wyoming—that was run by men. She was a strong supporter of women’s rights at the turn of the last century and politically active as a suffragette. These views seem to have led her to place certain women in central roles in Wyoming’s past that they did not in fact play. She portrayed them as strong-willed women who made things happen—women like herself.

|

Early life and education

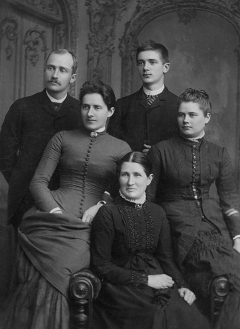

Grace Raymond Hebard was the third child of George and Margaret Hebard. Following their marriage, George and Margaret moved to New York City where he studied at Union Theological Seminary, graduating in 1857. George preached at a Presbyterian church in Clayton, N.Y., for a year before moving his wife and their first son, Frederic, to Clinton, Iowa, in March 1858. In Iowa Margaret gave birth to the couple’s daughters, Alice Marven on Feb. 21, 1859, and Grace Raymond on July 2, 1861.

Following the birth of their last child, George Lockwood, the family moved to Oskaloosa, Iowa, in 1869. But within a year George Hebard contracted pneumonia and died on Dec. 14, 1870. Margaret wanted all of her children to have college educations so she moved the family to Iowa City, home of the State University of Iowa, where she purchased a large house and rented out half of it as a source of income.

Grace’s education was very different from that of her siblings. As a result of almost continual ill health, she attended public schools for only two years. For the most part she was homeschooled by her mother. As she grew up, Grace saw her parents as pioneers, moving from New York to what was, in her mind, the western frontier. Watching her mother struggle to hold the family together while ensuring that all the children received a college education, Grace was determined to carry on the family’s pioneering spirit and acquire a degree in engineering at the university.

Being the only woman in her engineering courses, focusing primarily on surveying and mechanical drawing, Hebard received a good deal of criticism from her classmates, however. She graduated in 1882.

Drafting for the surveyor general’s office

Upon graduation Grace Hebard was offered a job working for the United States Surveyor General’s office in Cheyenne, Wyo., at the time in the process of surveying and mapping Wyoming Territory. With her mother Margaret’s asthma problems and the doctor’s suggestion that she would fare better at a higher altitude in a drier climate, the entire family moved to Cheyenne. Grace worked in the surveyor general’s office at the rate of $100 per month, a very generous salary for a 20-year-old woman in 1882. Her sister, Alice, found employment with the school district in south Cheyenne where she would work for more than 30 years.

Frederic opened a law office but still lived at home with the family to help with expenses. Lockwood became the organist at the Episcopal church, which the entire family, with the exception of Grace, attended. Grace did not attend church at all.

When she began working in the surveyor general’s office, Grace was one of 46 draftsmen employed there. She knew the work would not last indefinitely, however, so she began taking correspondence courses from the State University of Iowa to earn her master’s degree. Even though State University did not have a graduate school until 1900, its records did indicate that a Master of Arts degree was awarded to Hebard in 1885. She later claimed not to remember her thesis topic.

By 1889, there were only two individuals still working in the Surveyor General’s Office, and Grace’s job ended later that year when mapping work was completed. Upon leaving that position she received an appointment to work in what would become the state engineer’s office. Although she served as deputy engineer, Hebard did not like the work and received only $40 per month, a significant reduction in pay.

Making a place at the University of Wyoming

During her time at the surveyor general’s office, Grace cultivated a relationship with Edward C. David, the man who ran the office. David was also related by marriage to Territorial Representative Joseph M. Carey. Both men carried significant political influence.

In 1886, as construction began on the brand-new University of Wyoming, Hebard kept her eye on developments at the new school. Through her connections to the David and Carey families and with her brother Frederic’s election to the territorial assembly in 1888, she received an appointment to the University of Wyoming Board of Trustees in January 1891. In the spring of that year, Grace became the first member of her family to leave home. She boarded a train for Laramie, 49 miles away, and would work at the University of Wyoming until her death 45 years later.

Throughout her life, Hebard saw herself as a pioneer, but she was not the first woman appointed to the university’s board of trustees. Augustine Kendall of Rock Springs and Mattie Quinn of Evanston also served on the board. Hebard wasted little time moving to secure a position of power among the trustees, however. She was made the board’s paid secretary, and as such, produced all of the meeting minutes. With six of the nine trustees scattered across the state, Hebard and the other two board members living in Laramie made up the executive committee and had oversight of day-to-day operations at the school.

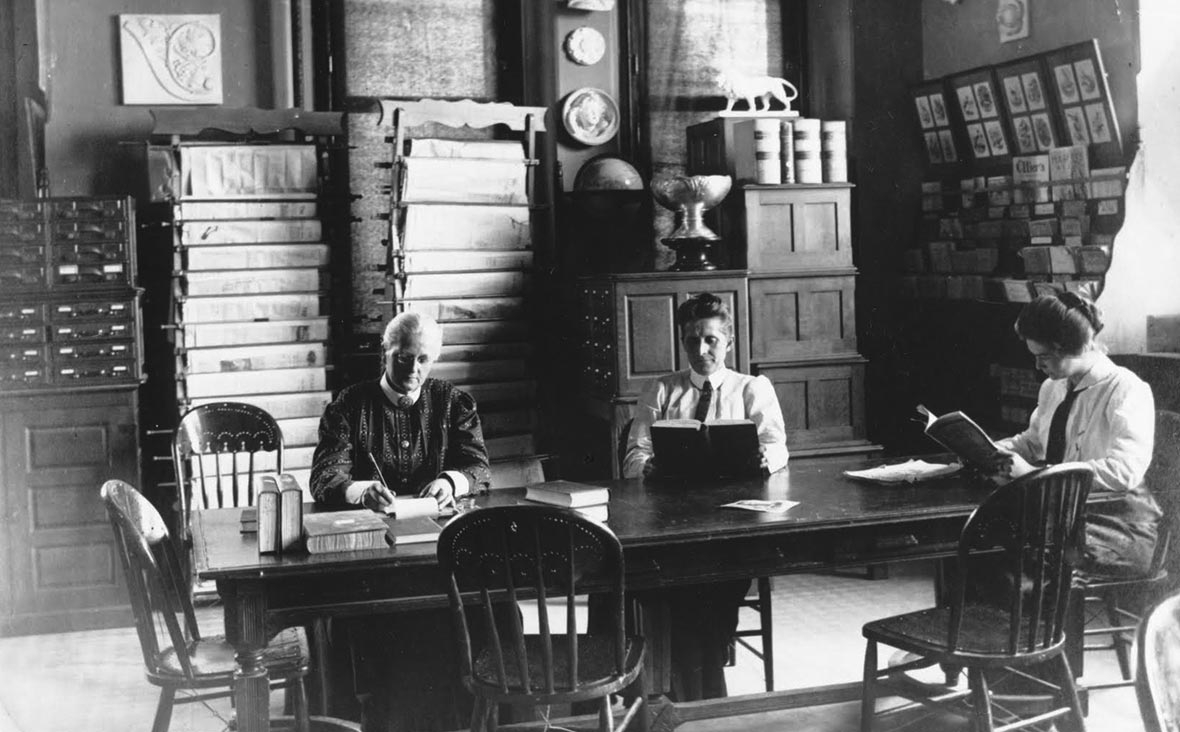

The following year the executive committee took over the responsibility of filling all faculty vacancies. During that period, Grace completed correspondence courses and received a Ph.D. in political economy from Illinois Wesleyan University. In 1894, with her Ph.D. in hand, Hebard was appointed librarian for the University of Wyoming. At the same time, she kept her position on the board of trustees. During the 1893-1894 academic year, she taught a correspondence course on constitutional history and took on the additional jobs of secretary for the correspondence school and the agricultural extension school.

When Frank Graves resigned as president of the university in 1898, the trustees considered hiring Hebard for the position, but she declined. She already held most of the power and influence at the university, and she was continuing with pioneering work in other areas. In 1898, Grace took and passed the Wyoming State Bar exam. Though she never practiced law, Hebard was the first woman in Wyoming admitted to the bar. In addition, she would become the Wyoming women’s tennis and golf champion.

These accomplishments would have been substantial for anyone; for a woman at the turn of the last century they were extraordinary. At the same time they seemed to instill in Grace a sense of infallibility. Soon, she and her ally, Board President Otto Gramm, became the targets of Wyoming journalists who said that no university employee or professor could hold a job at the school without Hebard’s approval.

Teaching political economy

In 1906, Hebard was appointed associate professor of political economy. Herbert Quaintance, already serving as a professor of political economy, opposed her appointment and insinuated that her Ph.D. degree was a fake from a disreputable school. With her influence at the university, Quaintance was forced out and his job given to Hebard, who was then named to head the Department of Political Economy and Sociology.

Grace claimed that she never sought the position, but only accepted the job to help the school. As a result of that shake-up, Hebard’s longtime roommate and History Department head, Agnes M. Wergeland, convinced Grace that she should begin studying the history of Wyoming and the West. Wergeland informed her friend that studying history would be a much “better hobby than trying to show everyone who was boss.”

Shaping history

Hebard took her friend’s advice and began researching the history of the West with a focus on Wyoming. A lifelong suffragette, Grace had a particular interest in women and their contributions to the discovery and settlement of Wyoming and the West. Even though she published books on Shoshone Chief Washakie, pioneers in the West, the Bozeman Trail and several editions of a book on the government of Wyoming, she became obsessed with two women—Sacajawea and Esther Hobart Morris.

In her writings Hebard insisted, in spite of documentation to the contrary that she was aware of, that Sacajawea—the young Shoshone interpreter for Lewis and Clark—lived to about 100 years of age and was buried on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming in 1884. Most scholars today agree there is much stronger documentation to show that Sacagawea, as the name is now more often spelled, died in 1812 at Fort Manuel Lisa on the Missouri River in what’s now North Dakota.

Hebard is probably best known in Wyoming for popularizing the Esther Hobart Morris story. Early in 1870, soon after the Wyoming Territorial Legislature had given women the right to vote and hold office, Morris was appointed justice of the peace in the gold-mining town of South Pass City.

Two generations later, Hebard and a surviving resident of early South Pass City, H. G. Nickerson, began telling the story that two candidates for the territorial legislature, Nickerson and William Bright, met with Esther Morris and others at Morris’s home—a story that Nickerson himself seems to have originated in 1916. According to this story, Morris extracted a promise from both men that whichever of them was elected to the legislature would introduce a bill supporting suffrage for women in Wyoming. Bright introduced the bill and it passed, giving women in Wyoming the right to vote and hold office.

Hebard described Morris as “The Mother of Woman Suffrage.” As with many of her other romanticized stories, Hebard found an individual—Nickerson—to corroborate everything she claimed as fact.

Hebard claimed that some of her information had been received in a letter from Bright’s wife, but the letter Grace wrote to Julia Bright was returned marked “addressee deceased.” By contrast, in a letter to the suffrage paper The Revolution, Robert Morris, Esther’s husband indicated that the first meeting between William Bright and Esther Morris did not take place until after the suffrage bill had been signed into law.

At no time during her life did Esther Morris ever claim to have had anything to do with the introduction or passage of the suffrage bill in Wyoming. And yet the story has shown remarkable staying power because people often seem to prefer the romanticized version to the facts.

Hebard was a dogged researcher who hunted for every bit of information she could find on her subjects. Problems arose, however, when the facts did not mesh with her often predetermined outcomes. Hebard’s papers in the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming are filled with documents—like the unread letter to Julia Bright—that contradict her often romanticized versions of events. That is, she knew what she was doing. She knew her work contradicted the work of distinguished historians and often times was not supported by the documents she herself located.

And though she won high praise for her work from all kinds of influential Wyomingites at her memorial service, peers more closely connected to her work seem not to have thought highly of it. The American Historical Review described her book on the Bozeman Trail as “commonplace history” adding “the most striking shortcoming is the deplorable English.”

The manuscript for Grace’s Sacajawea book was so poorly written that her publisher, Arthur H. Clark, hired Robert Cleland of Occidental College to ghostwrite it. Outside reviews of her manuscript of a book on the Pony Express, which was never published, described it as “poor grammatically,” “disjointed” and “decidedly poor, rambling, and pointless.”

Over the years, Grace Hebard involved herself in a number of other projects that were important to her. She spent a good deal of time traveling across Wyoming to mark the location of the Oregon Trail, work that was generally accurate. She took the leadership role in a project dealing with the Americanization of foreign-born immigrants. Working to organize a statewide Americanization program, she sent outlines of subjects she believed should be taught and tested to schools, courts, and individuals teaching citizenship courses. The subjects included the U.S. Constitution and early U.S. history

She also pushed for the adoption of child labor laws aimed at keeping youngsters in school and preventing businesses and individuals from taking advantage of children in the workplace. Hebard maintained involvement in the child labor and Americanization programs until her influence waned and recognition for her work decreased. She then moved on to other projects, usually associated with research and writing.

With her books on Washakie, Sacajawea, the Bozeman Trail and the Oglala Sioux war leader Red Cloud still in print almost 80 years after her death, and the ongoing popularity of the Esther Morris story, Grace Raymond Hebard still has an influence on the history of Wyoming and the West.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Cora M. Beach Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- Grace Raymond Hebard Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, box numbers 1, 2, 3, 16, 32, 42, 46, 55, 62, 63 and myriad folder numbers from each box.

Secondary Sources

- Beach, Cora M. Women of Wyoming. Casper, Wyo.: S. E. Boyer & Company, 1927.

- Clough, Wilson, O. A History of the University of Wyoming 1887-1937. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming, 1937.

- Hardy, Deborah. Wyoming University: The First 100 Years 1886-1986. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming, 1986.

- Hebard, Grace Raymond. Sacajawea: A Guide and Interpreter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with an Account of the Travels of Toussaint Charbonneau, and of Jean Baptiste, the Expedition Papoose. 1932. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications Inc., 2002.

- _________. “How Woman Suffrage Came to Wyoming.” Pamphlet, printer unknown, 1920.

- _________. Washakie: An Account of Indian Resistance of the Covered Wagon and Union Pacific Railroad Invasions of Their Territory. 1930. Reprint, Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- Mackey, Mike. Inventing History in the American West: The Romance and Myths of Grace Raymond Hebard. Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2005.

- Pearson, Lorene. “A Path-Breaker in Woman’s Activities.” The Relief Society Magazine, February 1934.

- Van Nuys, Frank. Americanizing the West: Race, Immigrants, and Citizenship, 1890-1930. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 2002.

- Wentzel, Janell M. “Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard as Western Historian.” Master’s thesis, University of Wyoming, 1960.

Editors’ suggestions for further reading and research

- Ewig, Rick. “Did She Do That?: Examining Esther Morris’ Role in the Passage of the Suffrage Act.” Annals of Wyoming 78, no. 1 (winter 2006): 28-34. The story that Esther Hobart Morris gave a tea party in South Pass City before the 1869 election to extract a promise from Bright and his Republican opponent, H.G. Nickerson, that whichever was elected would introduce a woman suffrage bill, was invented by Nickerson in 1916. Ewig examines the story’s roots and its remarkable staying power.

- Massie, Michael A. “Reform is Where You Find It: The Roots of Woman Suffrage in Wyoming.” Annals of Wyoming 62, no. 1 (spring 1990), 2-22. Accessed Sept. 27, 2013, at http://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom621231990wyom. The article contains especially good information about William Bright, South Pass City, the roots of the Esther Morris tea-party story and the personalities and politics leading to the bill’s passage.

- Scharff, Virginia. “Marking Wyoming: The West as Women’s Place,” her chapter on Grace Raymond Hebard in Twenty Thousand Roads: Women, Movement and the West. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, 93-114.

- Directions to the grave where the woman Hebard believed to be Sacajawea is buried are given in the Wind River Reservation field trip suggestion, below.

Illustrations

- All photos are from the Hebard Collection at the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks. Thanks too to Randy Brown of the Wyoming chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association for locating the marker in the 1915 photo. It still stands on a dirt road paralleling the trail and the North Platte River south of Lingle, Wyo.