- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Bighorn Basin: Wyoming’s Bony Back Pocket

The Bighorn Basin: Wyoming’s Bony Back Pocket

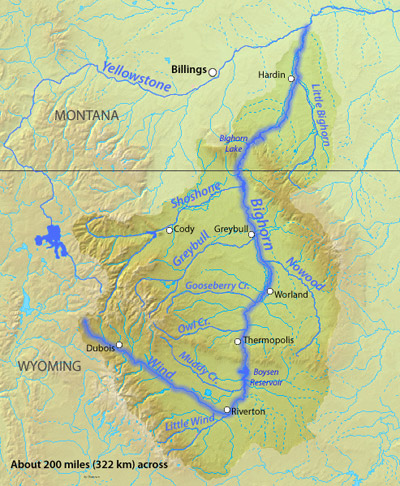

Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin is an oval scooped out of the northwest quadrant of the state and encircled by neatly aligned mountain ranges. If the basin were the face of a clock, the Bighorn Mountains would run from 1 to 5 o’clock; the Bridger Mountains from 5 to 6 o’clock; the Owl Creeks from 6 to 8 o’clock; the Absaroka Range from 8 to 10 o’clock; and the Bear Tooth Mountains from 10 to 11 o’clock.

The Pryor Mountains form a plug at high noon, with major rivers exiting on either side of it: The Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone River squeezes into Montana on the west and the Bighorn River gouges through Bighorn Canyon to the northeast. After that, the river arcs across the Crow Reservation. Both of these eventually join the Yellowstone River in Montana—the Clark’s Fork near Laurel and the Bighorn near Custer, Mont. The Yellowstone flows into the Missouri in North Dakota, and the Missouri joins the Mississippi in St. Louis, Mo., and empties into the Gulf of Mexico at New Orleans, La.

The major river of the Bighorn Basin—its namesake the Bighorn River—performs a trick. Rather than springing from any of the many ranges surrounding the basin, it sneaks in, already a full-grown river, from the south. John McPhee describes this stunt in Rising from the Plains. “The anomaly is so startling that early explorers, and even aborigines, did not put one and one together. To the waters on the south side of the mountains they gave the name Wind River. The waters on the north side they called the Bighorn. Eventually they discovered Wind River Canyon.”

The true headwaters of the Bighorn River are those of the Wind River near Union Pass in the Wind River Mountains. The crescent-shaped Wind River Valley is not usually referred to as a basin except by geologists describing the oil and gas reserves it holds deep underground, though it, too, is tidily hemmed by mountains. While the Bighorn Basin ranges from 4,000-6,000 feet in elevation, the Wind River perches at 5,000-7,000 feet.

During the Jurassic Era, about 160 million to 180 million years ago, the land that is now northwest Wyoming was located about where Cancun, Mexico, is today. Scientists believed the region was submerged in a marine environment called the Sundance Sea until a discovery made near Worland, Wyo., in the Bighorn Basin in 1997 changed this story. Thousands of petrified Jurassic dinosaur footprints indicate that there must have been enough dry land nearby to support terrestrial dinosaurs like theropods, a generic term for three-toed, meat-eating dinosaurs that walked on hind legs. Little is known about additional species that left tracks.

While the Bighorn Basin is rich with millions-of-years-old plant, vertebrate and invertebrate fossils, ancient signs of human history also exist. Where Medicine Lodge Creek flows out of the Bighorn Mountains, petroglyphs and a 26-foot-deep excavation by archaeologists show 11,000 years of continuous human occupation. The earliest known inhabitants were mammoth hunters. Pottery finds from Medicine Lodge Creek show the distinctive style of the Crow tribe, suggesting its members occupied north central Wyoming intermittently over the last 500 years.

In the 18th century the Eastern Shoshone, one faction of a group of Aztecan tribes from the southwest, shared the Bighorn Basin hunting grounds with the Flathead and Kootenai, until the Blackfeet, who had acquired firearms, pushed them all west. Members of the River Crow hunted in the Bighorn Basin during this century as well.

Fur trade and treaties

In the early 19th century, fur trappers explored the Bighorn Basin. Some of the first European explorers to enter the Bighorn Basin included John Colter and George Drouillard, two veterans of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery. Colter and Drouillard traversed the area east of what’s now Yellowstone Park along the Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone and the Bighorn River for fur trader Manuel Lisa in 1807.

Jedediah Smith, William H. Ashley and other trappers explored the basin in the 1820s, but this region’s pelt supplies and water routes proved less supportive of the fur trade than other watersheds. In addition, the basin was thick with grizzlies and mountain lions, which attacked more than a few explorers.

In the following decades, attempts from Euro-Americans to explore and wage war in the Bighorn Basin were largely fruitless, with livestock and supplies lost in river crossings and battles ending in disgrace. Meanwhile, several treaties made by the U.S. government with the tribes during the second half of the 19th century addressed the land in the Bighorn Basin as well as the Wind River Valley upstream.

The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie assigned much of present-day Wyoming to the tribes. The Bighorn Basin was designated for the Crow, which their enemies the Shoshone protested. But because they came from farther west, the Shoshone were not considered a plains tribe and therefore were excluded from the deal-making at Fort Laramie.

In the following years the Eastern Shoshone, led by Chief Washakie, continually asked for land to be reserved for them. In 1852, Washakie appealed to Brigham Young, governor and Indian commissioner in Utah Territory, for reservation lands, and in 1858 he asked for a Shoshone reservation at the Henry’s Fork of the Green River in the Uinta Mountains, in what’s now the southwestern corner of Wyoming. The 1863 Treaty of Fort Bridger assigned the Shoshone the land south of the Wind River Mountains, east of the North Platte River, and north of the Yampa River and Uinta Mountains with no boundary on the west, an area of approximately 44 million acres.

In 1868, however, as the Union Pacific Railroad was building across what soon would be come Wyoming Territory, a new Treaty of Fort Bridger drew the boundaries of the Eastern Shoshone tribe’s Wind River Reservation to the north, overlapping the Owl Creek and Wind River Mountains. Meanwhile, an 1868 Treaty at Fort Laramie reduced the Crow Reservation to land in Montana south of the Yellowstone River and east of the 107th meridian. The Crow Reservation was further restricted in 1880. The new treaties excluded tribal ownership of any lands in the Bighorn Basin.

Tribal conflict

Washakie was an ally to the whites, partly as a way to resist the power of Lakota and Crow people pushing in from the east and northeast. Washakie led the Eastern Shoshone to battle with the Crow on more than one occasion. Many years later, a white boy named Elijah Wilson who lived with Washakie’s family for two years described an unusually violent battle between the Shoshone and the Crow where hundreds lost their lives. This may have been the same battle for hunting grounds dated to 1866 by a roadside historical marker that overlooks a flat-topped mesa named Crowheart Butte, near Crowheart, Wyo. along the Wind River between Riverton and Dubois.

As legend has it, Washakie and Chief Big Robber of the Crow agreed to resolve the bloody battle in hand-to-hand combat on the butte’s flat summit. The winner’s tribe would take over the hunting ground. Washakie won the duel, and as a sign of respect for his opponent, mounted Big Robber’s heart on a lance.

Shrinking Indian lands

Congress created Yellowstone National Park on the west edge of the Bighorn Basin in 1872. That same year, negotiations between Indian Commissioner Felix Brunot and Chief Washakie resulted in the Shoshone relinquishing the southern third of the reservation near the South Pass mining claims in exchange for $25,000.

In 1877, Shoshone occupation of their reserved lands was further cramped when their enemies, nearly 1,000 Northern Arapaho, who in recent years had been roaming the Front Range of the Rockies from Colorado to Montana, were “temporarily” moved to the Shoshone Reservation. The Arapaho and Shoshone had battled one another as recently as 1874. Washakie insisted through the following years that the Arapaho be removed, but the situation became permanent.

Ownership of the Wind River Reservation was again compromised in 1887, when Congress passed the Dawes Act, parceling out Indian lands to individual tribespeople, many of whom then sold their land to whites.

Over the decades that followed, the amount of land owned by the tribes on Wind River fell to just a third of what it had been before the Dawes Act was passed. Land that was not claimed by Indians was sold to non-native settlers, railroads and corporations.

In 1896, a new treaty transferred 100 square miles in the northeast corner of the Wind River Reservation, including the mineral springs at present Thermopolis in Hot Springs County, from the tribe to the United States, and gave the Northern Arapaho tribe equal ownership of the Wind River Reservation.

Such intrusions onto Indian land, including the Wind River Reservation, continued until 1934 when the Indian Reorganization Act brought an end to the allotment process.

Ranching, irrigation and immigrants

The late 1870s and the 1880s brought cattle and sheep operations to the Bighorn Basin, starting with John Chapman’s Two Dot Ranch on a tributary of the Clark’s Fork River and Judge William Alexander Carter’s ranch on the Stinking Water River, later renamed the Shoshone River. Carter Creek and Carter Mountain are named for this rancher and the McCullough Peaks northeast of Cody are named for his foreman, Peter McCullough.

The German aristocrat Otto Franc von Lichtenstein, who in Wyoming shortened his name to Otto Franc, was one of a number of Europeans among the Bighorn Basin’s early ranchers. Franc established the famous Pitchfork Ranch along the Greybull River in 1879. (It was on the Pitchfork Ranch 102 years later that a dog brought in a black-footed ferret, a species that had been considered extinct for two years.) With the coming of the ranchers, bison were extirpated from most of their original range in the basin by the mid-1880s.

As in other parts of Wyoming Territory, the Bighorn Basin cattle industry boomed with an influx of capital and cattle early in the 1880s, and then withered due to overgrazing and harsh winters.

Wyoming became a state in 1890 and during this era several counties came into existence. In 1869, the entire Bighorn Basin in Wyoming Territory was part of Sweetwater County. In 1884, the northern part of Sweetwater County, including the basin, split off to become Fremont County. Big Horn County peeled off in 1890, Park County in 1906 and Washakie County and Hot Springs County followed in 1911.

In 1893, a group of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—built a tiny settlement on the Greybull River and began to dig an irrigation canal. This effort expanded to include more settlers and miles of canal. A strong Mormon presence still exists in the northern Bighorn Basin.

To the south, around Worland, German settlers were developing their own irrigation canals and beginning to grow sugar beets. During World War I, they were joined by Volga Germans who had migrated to Russia in the 1850s and then fled to Canada during the latter years of the 19th century.

Oil and a railroad

In addition to agriculture, the Bighorn Basin has produced substantial amounts of oil and gas. An oil seep was discovered in 1884, a dry hole drilled in 1888 and the first productive well struck in 1906. Through the 1930s, prospectors discovered and developed 54 oil and gas fields in the basin. In 1944, the first pipelines carried oil from the basin to Billings, Mont., and Casper and on to distant markets. New field discoveries continued through the 1950s, but declined sharply starting in the 1960s. As of 2008, nearly 2.87 billion barrels of oil and over 2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas had been produced from throughout the Bighorn Basin.

The 1900s also brought the Burlington Railroad. From 1900 to 1909, the railroad crept south from Montana up the Bighorn River to Kirby and Thermopolis. It took several years for workers to tunnel their way through formidable Wind River Canyon, but the railroad finally reached Casper in 1913, completing a railway circumnavigation of the Bighorn Mountains.

Engineers began to study the Bighorn River sites for dams to support irrigation in 1916. In the 1930s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studied the Bighorn River further, and in 1941, the Bureau of Reclamation issued a report recommending the upstream end of Wind River Canyon for a dam site. The Flood Control Act of 1944, more commonly known as the Pick-Sloan Program, encouraged water resource development in the Missouri River Basin to promote settlement. In 1946, preparation for a dam began. After sections of highway and railroad were moved, the contractors finally completed Boysen Dam in 1953. The project was millions of dollars over budget. Today, Boysen Reservoir attracts boaters, campers and fishermen throughout the summer, and its hydroelectric power plant generates electricity.

In 1946, engineers and geologists began studying the walls of Bighorn Canyon for stability, and in 1966 Bureau of Reclamation employees oversaw construction of 525-foot-tall Yellowtail Dam on the Bighorn River in Montana just north and downstream from the Wyoming-Montana border. The dam creates 70-mile-long Bighorn Reservoir, which spans the border, and the Yellowtail hydroelectric power plant generates power for thousands of homes in the surrounding region. The recreational opportunities at the reservoir fall under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, which has given concessionaire rights to the Crow Tribe.

Today, the badlands of the Bighorn Basin are just as stark as ever, and the irrigated river bottoms gleam with bright fields of sugar beets, melons, beans and other crops. The lush, high-elevation Green River Basin lured trappers and tie hacks to its waterways. The North Platte River invited pioneers, freight and stagecoach travel toward safe passage over the Continental Divide. The sweeping grasslands of the Powder River Basin incited violent rivalries between the Plains Indians and the U.S. Cavalry, between owners of small and large stockraising operations and between sheepherders and cattlemen. The Bighorn Basin, then, is the bony back pocket of Wyoming, its badlands home to more dinosaur than human footprints, hard-won irrigation projects hugging the banks of its rivers and rugged blue mountains jutting skyward from every distant horizon.

(Note: The U.S. Geological Survey uses “Bighorn” as a single word to refer to natural geographic structures–Bighorn Basin, Bighorn River, Bighorn Canyon, Bighorn Lake, Bighorn Mountains – and “Big Horn” as two words to refer to human establishments such as the towns and counties named Big Horn in Wyoming and Montana. The U.S.G.S. also lists “Big Horn” as a variant spelling for geographic features, and both spellings are used on maps and other published materials. Growing up in the town of Big Horn I learned to write my address or refer to my school with two words, and to describe the mountains with one word: the Bighorns.)

Resources

- Blevins, Bruce H. Big Horn County, Wyoming. Powell, Wyo.: WIM Marketing, 2000.

- Bureau of Land Management, Wyoming, Worland Field Office. “Red Gulch Dinosaur Tracksite.” Last updated Oct. 12, 2011. Accessed March 31, 2013, at: http://www.blm.gov/wy/st/en/field_offices/Worland/Tracksite.html.

- Hartl, Carolyn. “The Yellowtail Unit: Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program.” Bureau of Reclamation, 2001. Accessed April 8, 2013, at: http://www.usbr.gov/projects/Project.jsp?proj_Name=Yellowtail%20Unit&pageType=ProjectHistoryPage.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

- McPhee, John. Rising from the Plains. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1986, 54.

- Simonds, Wm. Joe. “The Boysen Unit: Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program.” Bureau of Reclamation History Program, 1999. Accessed April 8, 2013, at: http://www.usbr.gov/projects/Project.jsp?proj_Name=Boysen%20Division&pageType=ProjectHistoryPage.

- Stamm, Henry E. “Washakie’s Life and Times: A Biographical Sketch.” Excerpted from People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825-1900. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. Accessed March 31, 2013, at: http://www.windriverhistory.org/exhibits/washakie_2/life.htm.

- Stilwell, Dean P., Stan W. Davis-Lawrence and Alfred M. Elser, Ph.D. “Reasonable Foreseeable Development Scenario for Oil and Gas: Bighorn Basin Planning Area, Wyoming.” United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Nov. 8, 2010. Accessed April 9, 2013, at: http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/wy/programs/planning/rmps/bighorn/docs/rfds.Par.94367.File.dat/OilandGas.pdf.

- U.S. Statutes at Large 18 (1873-1875): 685-688. Treaty with the Eastern Shoshoni, 1863. Accessed April 7, 2013, at: http://www.windriverhistory.org/archives/treaty_docs/docs/1863-treaty.pdf.

- U.S. Statutes at Large 15 (1867-1869): 673-678. Treaty with the Shoshonee and Bannacks, July 3, 1868. Accessed April 7, 2013, at: http://www.windriverhistory.org/archives/treaty_docs/docs/1868-treaty.pdf.

- Woods, Lawrence M. Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin to 1901: A Late Frontier. Seattle: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1997.

Illustrations

- The maps of the mountains around the Bighorn Basin and of the Wind and Bighorn rivers are both from Wikipedia.

- The photo of the Bighorn River and Hot Springs State Park is by Ildar Sagdejev, from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Wind River Canyon, with the Burlington Railroad on the left and U.S. Highway 20 on the right, is by Talbot Hauffe of the Wyoming Department of Transportation. Used with thanks.