- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Covering Cattle Kate: Newspapers and The Watson...

Covering Cattle Kate: Newspapers and the Watson-Averell Lynching

On Saturday, July 20, 1889, eleven months before Wyoming became a state, a woman and a man were hanged from a pine tree in a gulch in the central part of the territory, not far from the Sweetwater River. The woman and the man were homesteaders. The six men who lynched them were cattlemen.

|

News stories about the hanging ran in the Cheyenne and Laramie papers just a few days afterwards. But the news didn’t stop there. Similar stories ran in Denver, Omaha, Chicago and New York.

The stories had only a few details consistently right: A man and a woman were hanged near the Sweetwater River on July 20. Almost all the other “facts” printed in these versions—who the victims were, who the lynchers were, exactly where the hanging took place, and, especially, why it happened—were wrong. And that was the way the lynchers wanted it. They wanted word to get out, as a warning, and they never tried to hide their participation in the deed. But they were circumspect about their motives.

Over the next several weeks, two newspapers closer to the event—the Casper Weekly Mail, and, in Rawlins, Wyo. the Carbon County Journal—got most of the details correct. Their reporters did this by interviewing people who had seen at least part of what had happened, and by interviewing others who had known the victims personally.

But because of the early, bad information from the Cheyenne Daily Leader, only the wrong versions became well known. These versions went out over the news wires and were quickly picked up by papers around the nation. By the 1920s, writers looking back to the events already accepted those incorrect versions as fact. Historians writing in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, relied in turn on these 1920s accounts as well as the original, false versions from Cheyenne. The false facts, after a while, seemed truer than ever.

Finally, in the 1990s, when two amateur history writers published books on the subject, the real characters of the hanging victims and the more complicated motives of their murderers began to come clear. These writers went back to the 1889 stories in the Casper and Rawlins papers. And they were the first to go back to the records of exactly who owned exactly what land along the Sweetwater in the 1880s. Finally, they found something like the truth.

Two homesteaders

The facts, as far as we now can tell, are these:

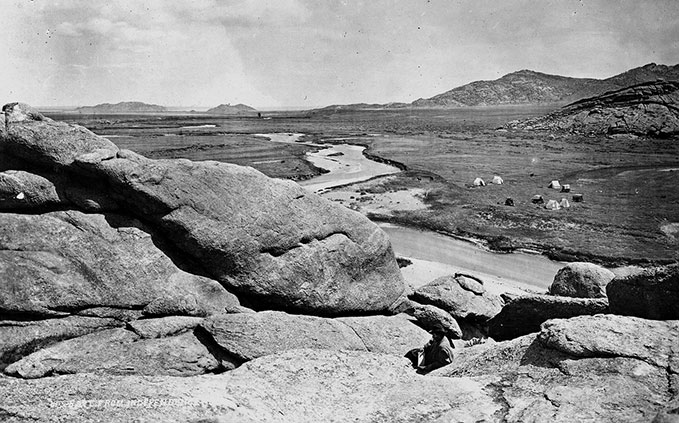

Jim Averell, a former soldier, cook, surveyor and rancher, built and stocked a store in the spring of 1884 where the road from Rawlins to Buffalo, Wyoming Territory, crossed the Sweetwater River. This was just a few miles downstream from Independence Rock, also on the east-west route of the old Oregon Trail, the famed Emigrant Road. Casper did not exist yet. The Rawlins-to-Buffalo road was one of the main routes north from the Union Pacific Railroad to the Powder River Basin in northern Wyoming, then filling up with cattle.

The cattle business was booming. Averell’s location would have been a good place to serve both traveling and local customers. He filed a claim on a quarter section—160 acres—of land and dug an irrigation ditch. He was at various times postmaster—the post office was for a few years named Sweetwater, Wyoming Territory—a notary public and justice of the peace. His name was sometimes misspelled as “Averill” in contemporary accounts.

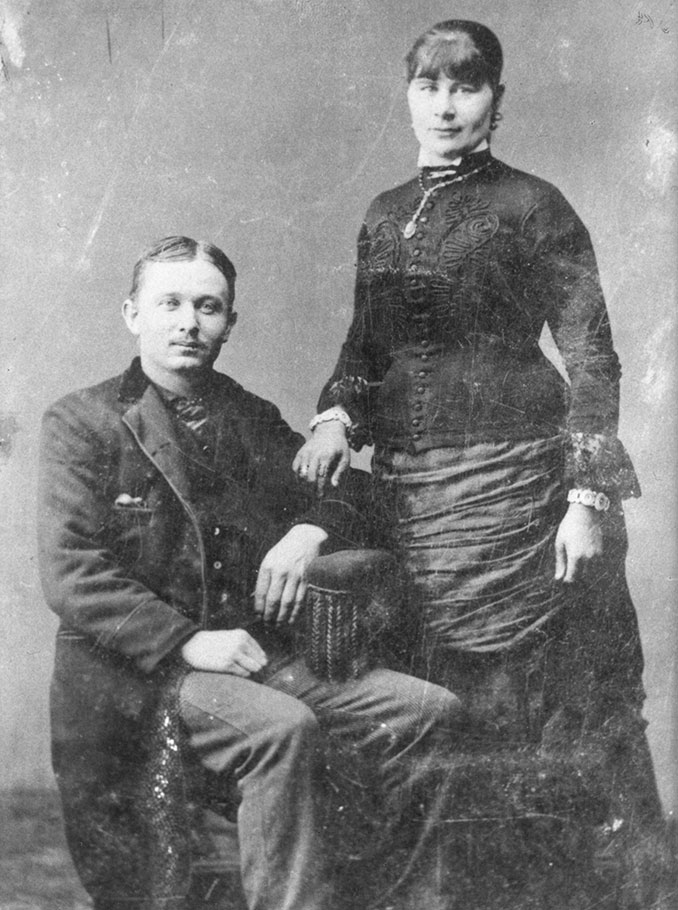

Ellen Watson, called Ella, ten years younger than Averell, joined him on the Sweetwater in the spring of 1886. She was from Kansas, where she had married at 18 and then divorced her abusive husband two years later. Averell probably met her in Rawlins. They filed that spring for a marriage license in Lander, but whether they actually got married is unclear.

By the summer of 1889 he had a store, a house, a stable, an icehouse and chicken coop on the property. These would have been low, small, dirt-roofed, rough log buildings. The store was also a saloon. Averell would have sold socks, cartridges, bacon, flour, coffee and whiskey. He also had a trout pond, 16 feet square.

Watson and Averell filed back-to-back, quarter-section land claims about two miles north up Horse Creek from where it joined the Sweetwater near Jim’s store. She had built one cabin—perhaps two—on that land, had fenced 60 acres of pasture and owned about 50 head of cattle by the summer of 1889. She also helped Jim run the store.

Six cattlemen

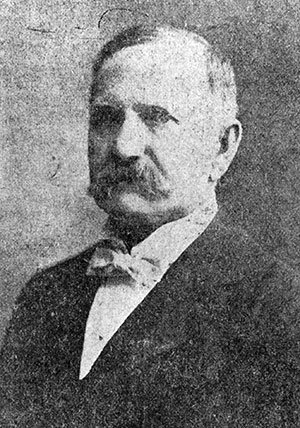

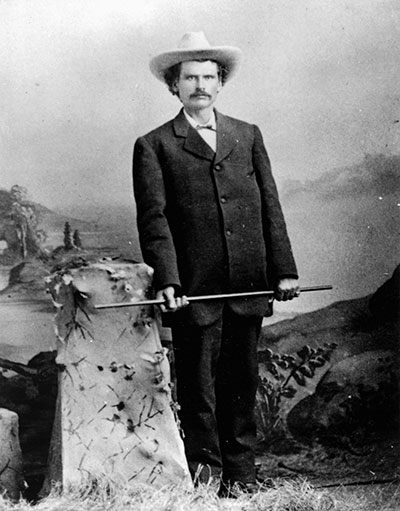

Tom Sun ranched at Devil’s Gate, about eight miles up the Sweetwater from Averell’s store. He was French-Canadian and probably came to Wyoming about the same time the railroad did, in the late 1860s. In 1883, he married a young Irishwoman named Mary Hellihan. By 1889 they had two children.

John Durbin and his brother Tom ranched up the Sweetwater from Sun. Their ranch was by far the largest on the Sweetwater. They also owned interests in meatpacking plants and in a Chicago cattle-marketing business.

Albert Bothwell first came to the Sweetwater valley in the mid-1880s, looking for mining, ranching and real estate opportunities. In 1885, he acquired the 76 Ranch, with its headquarters less than a mile from Averell’s store, but he did not start running cattle until the summer of 1888. He had a reputation for a bad temper.

Image

That same summer, Bothwell and a group of investors formed a company and founded the “town” of Bothwell about a mile west of Watson’s cabins and offered lots for high prices. Brochures described a town with a store, blacksmith shop, post office and a newspaper, the Sweetwater Chief, and indicated the railroad would soon link the Sweetwater Valley to Casper.

Robert Conner ranched a few miles up Horse Creek from Watson’s and Averell’s homestead claims. He was originally from eastern Pennsylvania, where his stepfather had made a fortune in the coal business.

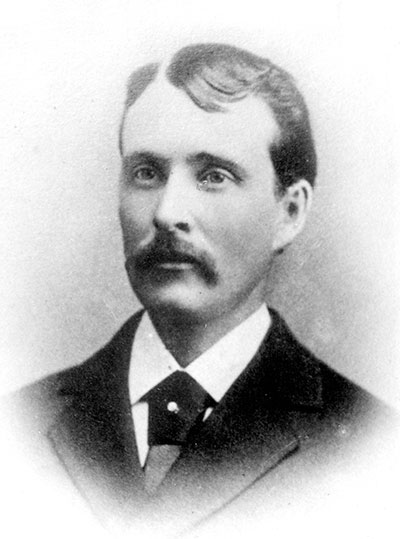

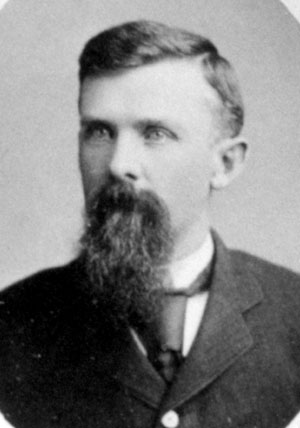

Robert Galbraith was a well-known master railroad mechanic from Rawlins and a member of the Territorial Legislature who visited the Sweetwater in July 1889 to buy a herd of cattle from Bothwell.

Ernie McLean was a cowboy who worked for John Durbin.

Cattle and land

For few years, in the early 1880s, some people made a lot of money in the cattle business in Wyoming. Soon, however, there were too many cattle. Many went unbranded, and cattle thieves—rustlers—took advantage of this confusion.

Then, with so many cattle coming to market, prices began to fall. Much of the range had been badly overgrazed. Then came one or two hot, dry summers and a winter so bad it’s still famous. Thousands of cattle died. Many ranchers quit. But prices stayed low, and the range was still overgrazed. Cattle theft was widespread, and the belief that rustlers were seldom or never convicted circulated even more widely, though at least one scholar who tested the claim against court records found it was exaggerated. In any case, these problems made business hard for all ranchers.

|

Nearly all the land still belonged to the government. To control the range where their cattle grazed, ranchers needed only to control the water. That is, it was necessary to own only small scraps of land with springs or creeks on them. But when people like Watson and Averell came along, fencing pastures for their small herds, digging irrigation ditches to water their gardens or building stores, it upset familiar ways of using the land. The owners of the large herds didn’t like it. Bothwell approached Watson two or three times about buying her land, but she refused every time. This would have angered him.

Averell was a surveyor, and familiar with land law. He and Watson formally questioned the legality of some of Durbin’s and Conner’s land claims. Then in February 1889, Averell wrote a letter to the Casper Weekly Mail warning people that the brand-new “town” of Bothwell was a scam: “just a geographical expression,” he put it, without a single house. Bothwell and his investors must have been infuriated. But Averell was essentially right. The only building in Bothwell, the Carbon County Journal noted a few years later, was “a shack” where its newspaper was published, the Sweetwater Chief. Bothwell and his partners needed customers to buy the expensive lots. The paper, of course, was there to advertise the town.

Twice each year, ranches got together to round up the cattle. In the spring, cowboys cut their ranches’ calves out from the rest and then branded them. In the fall, they separated the calves from their mothers and drove some to the railroad to ship to market. The spring roundup for the lower Sweetwater ended July 19, 1889, with a branding at Beulah Belle Lake, about eight miles west of Watson’s cabins on Horse Creek, on what’s now the Dumbell Ranch. Durbin, Sun and Bothwell, the bosses on that roundup, may have been talking for months about what to do about Averell and Watson.

The hanging

On Saturday morning, July 20, Durbin, Sun, Bothwell, Galbraith and McLean rode east toward Horse Creek. Sun was driving his buggy. The rest were on horseback. They stopped at the office of the Sweetwater Chief, where they found Conner talking with the newspaper editor. Then the six men rode to Watson’s ranch, where they tore down her fence, let her cattle out and threatened to kill her unless she got in the buggy. She got in.

They headed south toward Averell’s store but met him first, driving an empty wagon toward Casper for supplies. At gunpoint they forced him, too, into the buggy. To stay out of sight of the store, the cattlemen took a roundabout route to the Sweetwater River, and then headed west, upstream, for two miles. A friend of Averell’s named Frank Buchanan followed them at a safe distance.

Finally they left the river and headed up a gulch in the rocky hills south of Independence Rock. Buchanan got close enough to see Averell and Watson standing on a large rock under a limber pine tree. Two lariats had been slung over the biggest branch. A rope was around Averell’s neck. Watson was trying to keep McLean from getting the other rope around her neck, too.

Buchanan fired his revolver at the lynchers until he ran out of bullets. They fired back with rifles. Buchanan fled and rode as far as he could toward Casper, to the ranch of a man named Healy, who rode to Casper the next morning with the news. A man and a woman, he reported, had been hanged near the Sweetwater River. Buchanan had not stayed to watch them die, but his reports proved correct when a coroner’s jury found them Monday morning, still hanging, and cut them down.

All six lynchers were named in the first of two coroner’s inquests. Five of the lynchers were charged with the crime, and made bail by signing security bonds for each other. By the time a grand jury convened in October, one witness had died, and three others had left the territory. The case was dropped for lack of evidence.

The news reports

“Double Lynching,” ran the all-capitals headline in the Cheyenne Daily Sun the Tuesday after the crime. Averell, the newspaper reported, “kept a ‘hog’ ranch,” that is, a rural brothel. Watson, it added, “was a prostitute who lived with him and is the person who recently figured in the dispatches as Cattle Kate . . .”

A much longer story in the Cheyenne Daily Leader the same day charged Averell “and a virago who has been living with him as his wife” with cattle stealing. When the ranchers learned that her corral held 50 head of newly branded steers, the Leader reported, they decided they had to act. At night, 10 to 20 men snuck up on the cabin. Inside, Watson and Averell were playing cards and drinking whiskey.

The leader stationed a man with a rifle at each window and then led a rush on the door. “The sound of ‘Hands up!’ sounded above the crash of glass as the rifles were levelled at the strangely assorted pair of thieves,” the Daily Leader reported.

They were hanged, said the paper, from the limb of a big cottonwood tree by the riverbank. Averell supposedly whined and begged for his life. The woman stayed defiant, and “died with curses on her foul lips.”

“Cattle Kate”

Among all these inaccuracies and exaggerations, perhaps most interesting are the ones surrounding Watson’s name. The Sun confused her with a notorious and perhaps fictitious prostitute named Kate Maxwell, of the town of Bessemer, Wyo., west of Casper. Maxwell had figured in news stories earlier that year about the theft of money from a gambler.

Though the nickname “Cattle Kate” was used earlier about Maxwell, there is no evidence it was ever used about Watson in her lifetime. A close reading of the story in the Daily Leader shows that it uses no name for Watson at all. Nor does it call her a prostitute. (A “virago” is just a strong, loud woman.) And even though the other Cheyenne paper, the Sun, completely reversed its tone and gave a fairly factual account in a second story on July 24, the charge that she was a prostitute and the name “Cattle Kate” have stuck ever since.

Getting out the story

As long as there have been crimes, criminals have tried to avoid responsibility by making it look as though the victims deserved what happened to them. This seems to have been what the cattlemen were doing.

Word of the hanging, said the Daily Leader, came to Rawlins by “a special courier,”—a rider, that would mean. From Rawlins, the news was telegraphed to George Henderson, “who happened to be in the capital,” Cheyenne.

Henderson was foreman of the 71 Ranch on the Sweetwater, and a friend of Sun, Durbin and Bothwell. The courier was probably Ernie McLean, Durbin’s cowboy. Henderson was sympathetic with the lynchers and his boss years later wrote that Henderson was partly involved.

Durbin arrived in Rawlins the Sunday afternoon after the lynching and that evening took the train to Cheyenne. This would have put him in Cheyenne Monday morning, in time to work with Henderson to make sure the papers printed a version the cattlemen liked. The result, writes Daniel Meschter, the scholar who has looked most closely at these questions, was “a publicity campaign, for the management of the story from that point on was nothing less.”

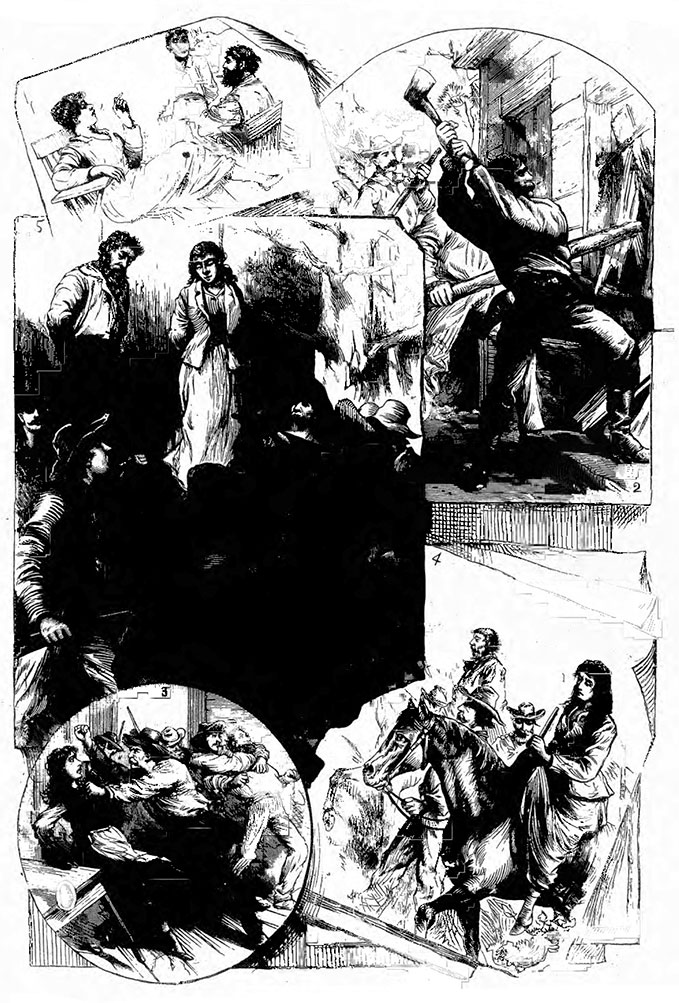

The campaign was immediately successful. Thanks to the news wires, the Cheyenne papers’ version went national, with a story in the New York World the same day. Three weeks later, the National Police Gazette--the National Enquirer of its time—went much further. “A Blaspheming Border Beauty Barbarously Boosted Branchward,” ran its headline, with a full page of dramatic illustrations of the capture and the gruesome death.

News versus history

The Casper and Rawlins papers worked more slowly—and their versions seem to have made little headway beyond their more limited readerships. Their reporters talked to people who knew what happened. Very soon, these two papers were claiming that land disputes, not cattle theft, were what the lynching was about.

“[T]he whole affair grew out of land troubles,” Averell’s friend Buchanan told the Casper Weekly Mail in a story published a week after the lynching. “Averell had contested the land Conners was trying to hold. He had made Durbin some trouble on a final proof [the last step before a land claim on public land could become private property] and had kept Bothwell from fencing the entire Sweetwater Valley. Averell favored the settling up of these lands in small ranches. Bothwell wanted the whole country and said that rich men did not need to obey the laws . . .”

Meschter found that the land records largely support Buchanan’s claims here. As for Bothwell’s ambitions, in the next few years he absorbed Averell’s and Watson’s land claims and water ditches into his own ranch.

And as so often happens, the most lurid version of the story—the one with sex in it—had the most staying power over time. Banker John Clay, George Henderson’s boss on the 71, was an influential, well-connected man and a good writer. In the early 1920s, he wrote in his memoir My Life on the Range that Watson “known as ‘Cattle Kate’ … was a prostitute of the lowest type, and while Averill [sic] and a man called Buchanan were her intimates, she was common property of the cowboys for miles around . . . ”

And when longtime Casper newspaperman A.J. Mokler wrote his History of Natrona County in 1922, he wrote that it was Watson, not Averell, who ran a “hog ranch,” that she had taken the name of Kate Maxwell, and that she was known to her friends as “Cattle Kate.”

Later writers picked up that version. When University of Wyoming Professor T.A. Larson first published his History of Wyoming in 1965, he was careful to separate fact from allegation. “Ella Watson, who was known thereafter as Cattle Kate, was variously described as a prostitute and Averell’s paramour [girlfriend]. … It was said also that she accepted stolen cattle from cowboys in return for her favors.”

The War on Powder River, published in 1966, is a thorough, lively history of the so-called Johnson County War, when about 50 Wyoming ranchers and hired Texas gunmen invaded Johnson County in northern Wyoming in 1892, to kill rustlers. The Watson-Averell lynching enabled the later invasion, argues author Helena Huntington Smith. And she severely criticizes the Cheyenne papers. But even Smith writes, “Ella was a prostitute who accepted recompense for her favors in the form of stolen yearlings and may have gotten in deeper. That is the accusation against her.”

Watson may have been a prostitute. There’s no way to know for sure. But by the time she was hanged in 1889, all her recorded actions—taking up a homestead claim, protesting the illegal claims of her neighbors, buying a brand for her cattle, signing a political petition, applying for a marriage license—show her as a woman who wanted to own land and be secure, and who wasn’t shy about her ambitions. These character traits may have been what got her killed.

As Wyoming moved that year toward statehood, the lynching must have made its women nervous—must have made everyone nervous, for that matter. Here they were, living in the only territory or state that allowed women to vote. At the same time they were living in a territory where a woman only recently had been hanged from the branch of a tree. It’s a troubling pair of facts. The papers owed it to their readers to get the facts right the first time out. Historians owe it to their readers to correct earlier errors. It’s never too late to get things right.

Resources

Primary Sources

Newspapers and Magazines:

- “A Double Lynching, Postmaster Averill and His Wife Hang for Cattle Stealing,” Cheyenne Daily Leader, July 23, 1889, p. 3, accessed July 1, 2014 via the Wyoming Newspaper Project, http://wyonewspapers.org/. This account is also reprinted in Armstrong, J. Reuel, Documents of Wyoming Heritage. Cheyenne: Wyoming Bicentennial Commission, 1976, which is in most Wyoming libraries.

- Casper Weekly Mail, August and September issues, 1889 includes a variety of reporting on and commentary about the lynching, including many reports from other newspapers. See especially “Press Comments on the Lynching Affair,” Aug. 2, 1889, p. 1; “Like a Lariatted Hyena,” Sept. 13, 1889, p. 5; “A Woman Talks,” Sept. 20, 1889, p. 8, and other stories without headlines in the same publication: Aug. 16, 1889, p. 4; Aug. 23, 1889, p. 1, accessed July 1, 2014 via the Wyoming Newspaper Project, http://wyonewspapers.org/.

- Carbon County Journal, August and September issues, 1889.

- Meschter, Daniel. Sweetwater Sunset (see below), reprints verbatim in its appendices, pp. 207-232, many of the Wyoming newspaper stories on the lynching that ran at the time, along with other pertinent documents.

- “Cattle Kate’s Career, A Blaspheming Border Beauty Barbarously Boosted Branchward, A Clandestine Cow-Catcher, Accomplice Averill Also Ascends the Airy Altitude, Deliberate Deeds of Daring.” The National Police Gazette, Aug. 10, 1889. Heavily illustrated. A scan of this article is available from the Casper College Western History Center.

Court records:

- The office of the District Court in Rawlins, Wyo., has kept copies of a number of documents from 1889 relating to the Watson-Averell lynching. These include inventories of Watson’s and Averell’s property and household goods after they died; records of one of the two coroner’s inquests; records of a lawsuit brought against Durbin and Bothwell for having stolen Watson’s cattle and records of the criminal case that was brought against five of the six lynchers in October 1889. The case was dropped because all witnesses by then had died or left.

Wyoming archives:

- A rare photo of Watson and her first husband, William Pickell, reproduced here, as well as some land-claim maps Averell worked up for survey customers, are in the Hufsmith and Anderson collections at the Casper College Western History Center.

Secondary Sources

- Hufsmith, George W. The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press, 1993. Hufsmith was the first author to go back to the land-claims evidence to support his contention that land, personalities and economics drove the lynchers to their crime much more than cattle rustling did. This book is in all Wyoming libraries.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska, 1965, 269-270.

- Meschter, Daniel Y. Sweetwater Sunset: A History of the Lynching of James Averell and Ella Watson near Independence Rock Wyoming on July 20, 1889. Wenatchee, Wash.: privately published, 1996. Meschter’s was the second book to go back to original records, and he does a more careful, organized and thorough job than Hufsmith did. This book is in public libraries in Rawlins and Hulett, Wyo., and at Casper College.

- Rea, Tom. Devil’s Gate: Owning the Land, Owning the Story. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, 168-191. This account includes much more background on the cattle business, politics and land laws of the time, and takes advantage of Hufsmith’s and especially Meschter’s scholarship.

- Smith, Helena Huntington. The War on Powder River: The History of an Insurrection. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966. See pp. 121-134 for Chapter Eighteen, “The Crime on the Sweetwater.” Smith comes down hard on the newspapers, and also contends that the failure to prosecute the lynchers encouraged the cattlemen’s extralegal invasion of Johnson County three years later.

- Van Pelt, Lori. "Cattle Kate: Homesteader or Cattle Thief?" Wild Women of the Old West, edited by Glenda Riley and Richard W. Etulain. Golden, Colo.: Fulcrum Publishing, 2003, 154-176; 208-209. A carefully balanced, well-documented account that pays close attention to the rustling question.

For Further Reading:

- Wikipedia. "List of lynching victims in the United States," accessed Dec. 31, 2019 at https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_lynching_victims_in_the_United_S.... The list is only partial, but includes one woman in the United States lynched before Watson and Averell were, and several in later years.

- West, Hannah. “Setting Cattle Kate’s Story Straight.” Casper Star-Tribune, July 25, 2008, accessed June 30, 2014, at http://trib.com/features/weekender/setting-cattle-kate-s-story-straight/article_85ecdb0b-94d5-5fe0-8bde-b59728a68115.html. As recently as 2008, Watson’s relatives were gathering every other year to compare new details and defend her reputation.

Illustrations

- The photo of Ella Watson and her first husband, William Pickell, is from the Hufsmith collection at the Casper College Western History Center.

- The Averell, Galbraith, Sun and Durbin photos are all from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The 1912 photo of the Watson cabin is from the Lora Nichols collection at the Grand Encampment Museum in Encampment, Wyo. Used with thanks, and with special thanks to Nancy Anderson of the Hanna Basin Museum in Hanna, Wyo., who located and first scanned it.

- The photo of the Sweetwater was taken by William Henry Jackson in 1870, and is from the photo library of the U.S. Geological Survey. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the hanging tree is by the author.