- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Coal Slurry: An Idea That Came and Went

Coal Slurry: an Idea that Came and Went

The waterways of Wyoming were named by pessimists. Salt Creek. Powder River. Poison Creek. There’s water in these?

In 1973—not coincidentally after the energy price spike caused by the Arab oil embargo—a group of companies formed Energy Transportation Systems, Inc., to build a pipeline to carry millions of tons of crushed coal each year from Wyoming’s coal-rich Powder River Basin to coal-burning electric power plants as much as 1,800 miles away in Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana.

The coal would be carried in water—a lot of it—the very water those pessimists were so skeptical about. Planners projected using 20,000 acre-feet of that water each year to carry 37.4 million tons of coal. (An acre-foot is enough water to cover an acre of land a foot deep—around 326,000 gallons.)

Executives of the railroads, which until then shipped out all Powder River Basin coal, were not enthusiastic. ETSI was a joint venture of Bechtel, Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb, Kansas-Nebraska Natural Gas Co., United Energy Resources and Atlantic Richfield.[1] Frank Odasz, who was ETSI’s chief representative and lobbyist in the Rocky Mountain region for the project, explained Burlington Northern Railroad was initially a minor investor. “I think they did it just to spy on us,” he said.[2]

Coal slurry pipelines have had a brief and not terribly illustrious history in the United States. The first was built in Ohio in 1957 for Consolidation Coal Company, but was shut down in 1963 in the face of fierce competition from the railroads. The only coal slurry line operating in the United States after that was the 273-mile Black Mesa line, which moved five million tons of coal annually from Arizona’s Black Mesa Mine to the 1,500-megawatt Mohave power plant in Nevada. The Black Mesa line opened in 1969.

With the 1973 Arab oil embargo and the accompanying price spike, coal became an even more attractive power-plant fuel. It is abundant and inexpensive in the United States, though it is also dirty and bulky. Most coal is hauled by coal unit trains—100 rail cars with 100 tons of coal in each.

During the coal boom of the 1970s, slurry pipelines were proposed as an alternative to rail transport. Coal would be crushed, then mixed with water to create a slurry and sent via pipeline to its destination, where the mixture was dried, then burned. When in the pipeline, the slurry moved along at a leisurely four miles an hour.

The first proposed project using Wyoming coal—and Wyoming water—was the ETSI project. Aware that any proposal to export a lot of state surface water would be dead in the, uh, water, the company found a previously unknown source for its project, the Madison Formation aquifer, thousands of feet underground. The company planned to drill deep wells in Niobrara County in eastern Wyoming, pumping out about 20,000 acre-feet a year.[3]

In February of 1974, then-Gov. Stan Hathaway signed a pipeline bill that would allow water rights for underground water. This was a clear nod to ETSI—the only project then on the table—giving the company the tentative go ahead. Some ranchers and other shallow-well users in Niobrara County worried that ETSI’s well field would draw down their wells. The company signed an agreement with the state engineer promising to replace any water lost to individual users from their activities.

In the U.S. Congress, Democratic Rep. Teno Roncalio of Rock Springs, Wyo., opposed taking any water from existing uses to operate slurry pipelines. Roncalio also opposed a later bill that would have given the pipelines the right of eminent domain to force the railroads to give the pipelines rights of way across their tracks.

Roncalio was a strong supporter of the railroads. He and ETSI representative Odasz engaged in vigorous debates on the topic. Both were also serious competitive tennis players. Odasz once suggested to Roncalio that “we show them how politics is done in Wyoming” by partnering as a doubles team in a state tennis match. The two did, and won their division.

For the ETSI project, the water would be piped to Gillette, Wyo., where about 37.4 million tons of coal from three Powder River Basin mines would be shipped to plants in Kansas, Oklahoma and Arkansas. Reporter Warren Wilson said in a Casper Star-Tribune article published Nov. 14, 1978, that ETSI could deliver coal via pipeline for about $7 a ton, while the railroad charged $11.80 per ton. In 1979, the federal Office of Technology Assessment estimated4 slurry charges at about $6.50 a ton, with rail rates to the same destination costing $9.10 per ton.

Railroad officials vigorously opposed the ETSI project. In order to get from Gillette to darkest Arkansas, the pipeline had to cross 65 rail lines. The railroad companies refused to allow the pipeline to cross in each and every instance. Lacking either state or federal eminent domain authority, ETSI was forced to sue for each right of way individually. The company won all 65 court cases, and all six of the appeals that were filed[4]. ETSI executives then tried to get the right to condemn the crossings via eminent domain at both the state and federal levels, but never did.

By the summer of 1978, according to a story[5] in the Casper Star-Tribune, the ETSI pipeline was “on the verge of construction.” Wyoming Gov. Ed Herschler told the subcommittee on public lands and resources of the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee that federal eminent domain wasn’t necessary.

The railroad officials were unmoved. Ed Sencabaugh, a special representative with Union Pacific, told[6] High Country News, “The railroads are perfectly capable of hauling all the coal produced in the western coal fields. In addition we can deliver to small users as well as the large ones. Slurry lines only deliver large volumes of coal. It’s just a cream-skimming method—taking all the biggest customers and depriving the railroads of desperately needed income.”

Odasz made hundreds of presentations to boost the ETSI pipeline at various local meetings in the several states affected by the project. Considering the tradition in agriculture about how valuable western water is, opposition from that corner was relatively subdued. Some ranchers opposed the project. A 1975 Wyoming poll[7] had indicated that most people opposed the coal slurry line, but favored industrial development. No state environmental group took a position on the ETSI line, except The Wilderness Society. That group’s representative, Bart Koehler, wandered a little afield from his usual interests to oppose it before the Wyoming Legislature.

Odasz was the only representative of any industrial project of the period in Wyoming who actively courted the environmental community, which may help explain their relative silence on the issue.

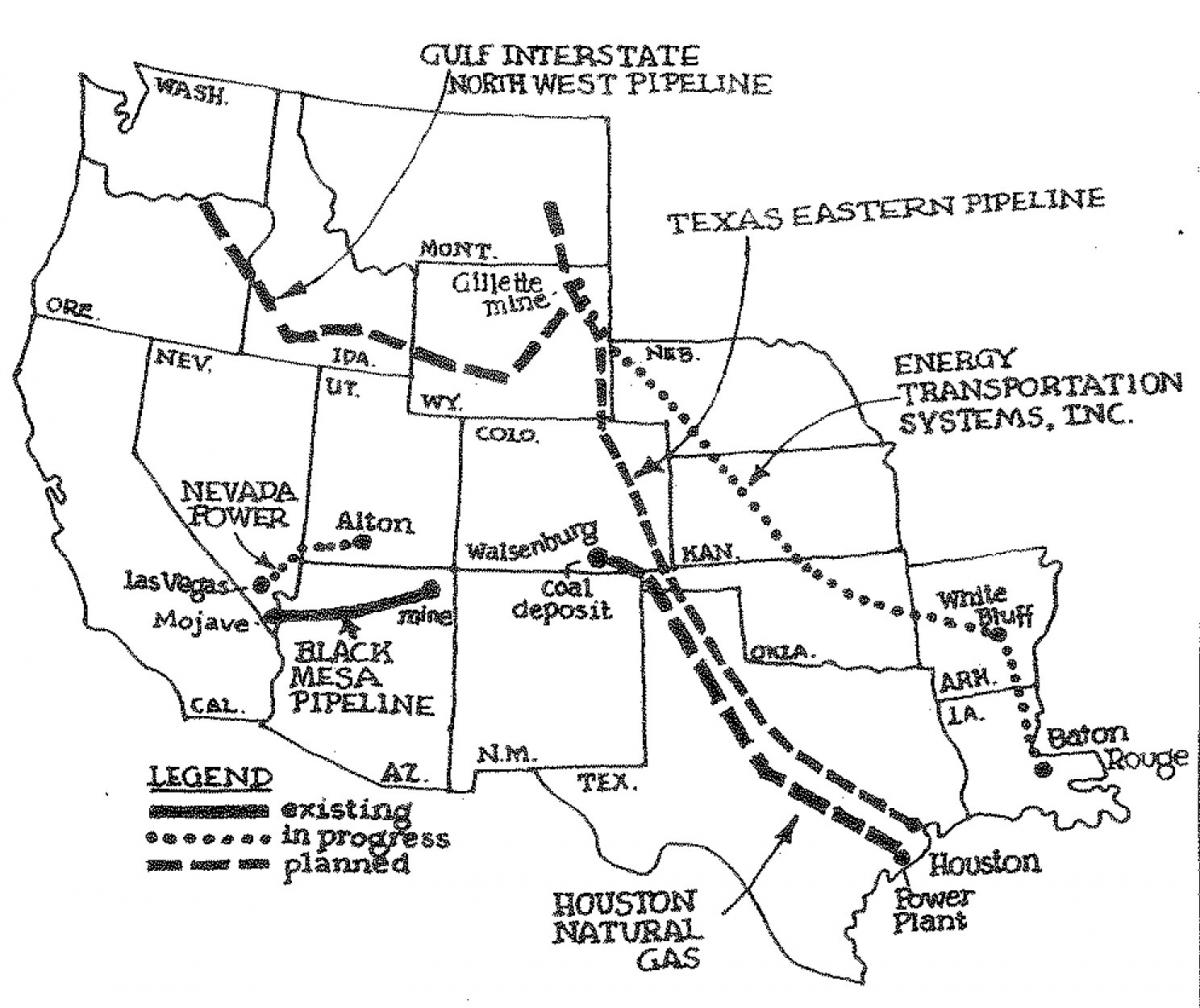

ETSI’s stuttering progress attracted interest from other companies, and pretty soon coal slurry pipeline proposals were sprouting all over the West. Ten were discussed in various levels of seriousness, and five were actually mapped out—from Walsenburg, Colo., to Houston; from Alton, Utah, to Las Vegas; ETSI’s, of course, from Gillette to Arkansas; the Gulf Northwestern Pipeline from Gillette to Oregon and Washington; and the Texas Eastern Pipeline from Montana and Wyoming to Houston.

Image

The Texas Eastern proposal was where the whatchamacallit hit the fan. The company wanted to take 20,000 acre-feet of water from the Little Bighorn River in southern Montana to move 25 million tons of coal per year from Decker, Mont. and Gillette 1,200 miles to Houston. Montana’s Crow tribe claimed all 110,000 acre-feet of water in the Little Bighorn, which runs through its reservation. Courts had not yet settled the issue, however, and it was tied up in competing claims and counterclaims among Montana, Wyoming and the tribe that made Custer’s nearby 1876 battle look like a minor tiff among friends.

In February of 1979, the Powder River Basin Resource Council and the Wyoming Outdoor Council opposed[8] the Texas Eastern proposal. At the end of February, Gov. Ed Herschler allowed a bill to become law without his signature[9] allowing Texas Eastern to use 20,000 acre-feet of water annually from the Little Bighorn.

Montana Gov. Tom Judge said his state would sue if Wyoming appropriated water for the slurry project without his state’s approval.

In March of 1979, Herschler held a hearing in Sheridan, Wyo. on Texas Eastern’s proposal. About 800 people attended and nearly 50 testified. Reaction ran heavily against the idea.

An unidentified source at one of the other companies exploring slurry transport told High Country News[10], “We looked at this water source and thought it was really a can of worms. Our lawyers said that a good case could be made on either side of the question, but they thought they could win it. However, they also said it would take 10 or 15 years to finally settle the issue, so we abandoned it.”

Phil Roy, a lawyer for Montana’s Blackfeet tribe, called the Texas Eastern proposal “the most blatant, ill-timed raid on the water of Wyoming and Montana in the history of those two great states.”

The other proposal for a Wyoming pipeline—the Gulf Northwestern pipeline from Gillette to Oregon and Washington—apparently never got much past the talking and map-drawing phase.

All of this sound and fury ended up signifying nothing, as Shakespeare says. Or as far as actual construction goes, very little. None of these slurry pipelines were ever built. ETSI, generally viewed in the business community as the strongest proposal, lost about $145 million. Odasz said that he was not privy to the decision to cancel the ETSI project, which died a quiet death in 1984[11].

ETSI was beaten out by Chicago & Northwestern Railroad for major coal supply contract with Arkansas Power & Light, which may have contributed to its demise. In 1983, Texas Eastern became the project manager for ETSI. Then, in August 1984, the Wall Street Journal reported that Texas Eastern was abandoning its plans for a slurry line. The opposition from the railroads is the most frequently cited reason for the demise of the slurry lines.

In 1989, a jury awarded the ETSI pipeline group up to $1 billion in damages, finding that the Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corp. had conspired with other railroads—including Burlington Northern and Kansas City Southern—to stop the project[12]. The other railroad companies had settled ETSI’s claims out of court for about $285 million. Santa Fe Southern Pacific had been expected to do the same, but decided instead to make its case in court, where it lost. Santa Fe eventually agreed to pay $350 million.[13]

The Black Mesa coal slurry line was shut down in December 2005 when the Mojave power plant closed.

The ETSI project had finally petered out in a climate of falling energy prices and rising concern about water rights in the West.

Resources

- Anderson, Robert. “Emotional water issues clog ETSI’s pipeline.” High Country News, Feb. 20, 1981.

- Casper Star-Tribune, Feb. 16, 1975; May 18, 1978; Feb. 9, 1979; Feb. 24, 1979.

- Coffey, George R. and Virginia A. Partridge. “Coal Slurry Pipelines: The ETSI Project,” International Right of Way Association, August 1982.

- Gaines, Sallie. “Santa Fe Settles Pipeline Suit.” Chicago Tribune, business section, April 20, 1990. Accessed May 22, 2014 at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1990-04-20/business/9002020166_1_coal-slurry-pipeline-powder-river-basin-settles.

- Journal of Commerce. “Expensive Defeat for Santa Fe: $345 Million Verdict Against Rail Firm Could Rise.” Chicago Tribune, business section, March 14, 1989. Accessed May 22, 2014 at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1989-03-14/business/8903260754_1_santa-fe-railway-million-verdict-million-judgment.

- Michelsen, Ari M. and John W. Green. Status, Issues and Impacts Of Coal Slurry Pipelines On Agriculture and Water, Technical Report 51. Colorado Water Research Institute. Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, 1988. Accessed May 10, 2014 at http://digitool.library.colostate.edu///exlibris/dtl/d3_1/

apache_media/L2V4bGlicmlzL2R0bC9kM18xL2FwYWNoZV9tZWRpYS84MTYxMA==.pdf. - Odasz, Frank. Interview by author, Casper, Wyo. April 3, 2014.

- Reuters. “Pipeline Group Awarded $1 Billion in SFSP Lawsuit.” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1989. Accessed May 9, 2014, at http://articles.latimes.com/1989-03-11/business/fi-769_1_santa-fe-southern.

- U.S. Department of Interior. Bureau of Land Management. Draft Environmental Impact Statement on the Energy Transportation Systems Inc. Coal Slurry Pipeline Transportation Project. Denver, Colo.: November 1980, 1-1.

- Whipple, Dan. “Slurry carries coal, water and controversy.” High Country News, April 6, 1979.

Illustrations

- The photo of Frank Odasz is from the Casper Star-Tribune Collection at the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Gov. Stan Hathaway is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The map of coal slurry pipeline routes was drawn by Kathy Bogan and published in High Country News in 1979. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Rep. Teno Roncalio, D-Wyo. by his son, Frank Roncalio, is from p. 238 of Pinedale, Wyoming: A Centennial History 1904 – 2004, by Ann Noble. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the BNSF coal hoppers in the train yard at Guernsey, Wyo. is by Tom Rea.

Footnotes

[1] Bureau of Land Management. Draft Environmental Impact Statement on the Energy Transportation Systems Inc. Coal Slurry Pipeline Transportation Project. November 1980. Page 1-1.

[2] Author’s interview with Frank Odasz, April 3, 2014.

[3] “Emotional water issues clog ETSI’s pipeline,” by Robert Anderson, High Country News, Feb. 20, 1981.

4 “Slurry carries coal, water and controversy,” by Dan Whipple, High Country News, April 6, 1979.

[4] “Coal Slurry Pipelines: The ETSI Project,” by George R. Coffey and Virginia A Partridge. International Right of Way Association, August 1982.

[5] Casper Star-Tribune, May 18, 1978.

[6] “Slurry carries coal, water and controversy,” by Dan Whipple, High Country News, April 6, 1979.

[7] Casper Star-Tribune, February 16, 1975.

[8] Casper Star-Tribune, February 9, 1979.

[9] Casper Star-Tribune, February 24, 1979.

[10] Slurry carries coal, water and controversy,” by Dan Whipple, High Country News, April 6, 1979.

[11] Status, Issues and Impacts Of Coal Slurry Pipelines On Agriculture and Water, Technical Report 51, Colorado Water Research Institute, Colorado State University, by Ari M. Michelsen and John W. Green.

[12] Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1989. http://articles.latimes.com/1989-03-11/business/fi-769_1_santa-fe-southern.

[13] Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1990. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1990-04-20/business/9002020166_1_coal-slurry-pipeline-powder-river-basin-settles.