- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Teapot Dome Scandal

The Teapot Dome Scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s involved national security, big oil companies and bribery and corruption at the highest levels of the government of the United States. It was the most serious scandal in the country’s history prior to the Watergate affair of the Nixon administration in the 1970s.

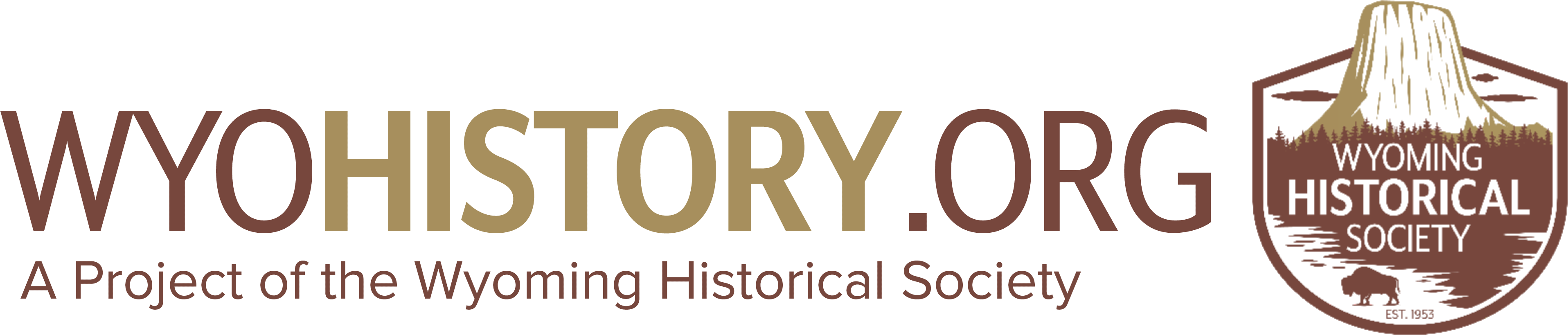

And this controversy was named for an oil reserve near a rock formation north of Casper, Wyo., that looked just like a teapot.

Events that led to the scandal began decades before when government and U.S. Navy officials, contemplating a new, global presence, realized they needed a fuel supply that was more reliable and more portable than coal.

During the Theodore Roosevelt presidency early in the 20th century, Department of the Navy officials aspired for an American navy that could sail all the world’s oceans, demonstrating the country’s newly found imperial powers. The U. S. Navy, bound by weight limitations with coal-fired ships, resorted to building coal-fueling stations around the world.

They watched carefully as other nations began development of petroleum-powered ships. Beginning in 1909, during the Taft administration, Navy administrators decided to convert the fleet to the more efficient petroleum. Ships would have no need for coaling stations. Once fueled, the petroleum-powered ships had far greater range.

The USS Wyoming, a battleship initially launched in 1900, became the first ship in the fleet to be converted to oil power in 1909. (The vessel was later renamed the USS Cheyenne when the new battleship USS Wyoming was launched in 1910.), As more ships were converted from coal, Navy officials grew more concerned about the long-term availability of oil. What would happen if oil were to run out? The Navy would be paralyzed.

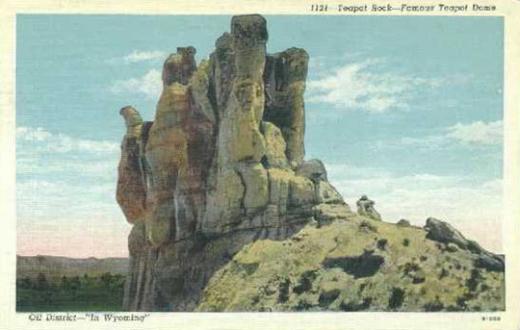

Consequently, Navy administrators asked Congress to set aside federally owned lands in places where known oil deposits most likely existed. These “naval petroleum reserves” would not be drilled unless a national emergency made it necessary. One of the three petroleum reserves set aside was near Salt Creek in northern Natrona County in a place named for an unusual rock formation nearby—Teapot Dome. A dome is a geological formation that traps oil underground between impervious layers of rock, with the upper layer bent upward to form a dome.

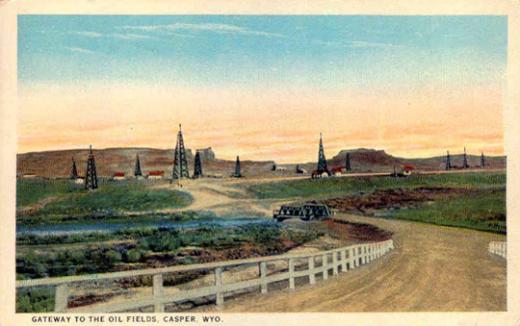

Oilmen throughout the West coveted the opportunity to drill within these federally owned reserves. Soon after Republican Warren G. Harding was elected president in 1920, he appointed his poker-playing friend, U.S. Sen. Albert Fall, to be his secretary of Interior.

Fall, a rancher and New Mexico’s first U.S. senator, accepted the cabinet post. Within a few weeks, he convinced President Harding to allow transfer of the naval petroleum reserves from the Navy to the Department of the Interior, arguing that the department was “better able” to oversee the protection of these areas where oil was not to be produced, but kept in case of emergency.

What resulted became known as the Teapot Dome scandal, but even though the scandal gained its name from a Wyoming place, the wrongdoers were from elsewhere.

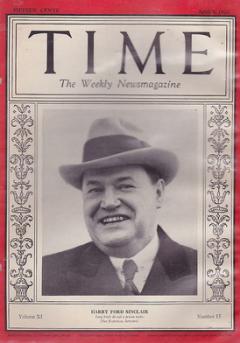

Secretary Fall, once the Teapot Dome oil field was under his control, made secret deals with two prominent oilmen, Edward Doheny and Harry Sinclair. Both men, close friends of Fall, paid him bribes to authorize them to drill in the three naval petroleum reserves—contrary to the letter and spirit of the law.

Back in Wyoming, independent oilman and later, Democratic Wyoming Gov. Leslie Miller became suspicious when he saw trucks with the Sinclair company logo hauling drilling equipment into the Teapot Dome naval petroleum reserve. He asked U.S. Sen. John B. Kendrick, also a Democrat, to look into the matter. Kendrick, sensing wrongdoing, turned the question over to a special Senate investigating committee.

Meanwhile, President Harding took a summer trip west, stopping in Wyoming, enjoying Yellowstone and continuing on to Alaska and, eventually, to San Francisco. While there, the President died suddenly. Some historians believe Harding escaped impeachment for his role in Teapot Dome by having the “good fortune” of dying as the scandal was unfolding. Of course, such a conclusion cannot be proven.

Fall was not so lucky. Following a lengthy Senate investigation, he was tried for accepting bribes. He was convicted and sent to federal prison, the first Cabinet-level officer in American history to go to jail for crimes committed while serving in office.

Both Sinclair and Doheny were exonerated of the main charge—giving bribes to Fall. As a newspaper reporter observed when the two wealthy oilmen were found not guilty, “You can’t convict a million dollars.” Sinclair was sentenced to a 9-month prison term not for bribery but for contempt of Congress, and for charges connected to his hiring of detectives to trail members of the jury in the original bribery trial.

The federal government brought suit in federal court in Wyoming to cancel the bribery-induced leases to Teapot Dome that Fall had given to Sinclair. Wyoming’s U.S. District Judge T. Blake Kennedy ruled against the government, but the leases were finally cancelled when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Kennedy decision.

Resources

- “Harry Sinclair.” NNDB. Accessed Aug. 22, 2012, at http://www.nndb.com/people/808/000173289/.

- McCartney, Laton. The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding White House and Tried to Steal the Country. New York: Random House, 2008.

- Stratton, David H. Tempest Over Teapot Dome. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

- Rosenberg Historical Consultants. Tour Guide: Salt Creek Oil Field, Natrona County, Wyoming. Casper, Wyo.: Natrona County Commission, 2003.

Illustrations

- The postcard images of Teapot Rock and the Salt Creek oil field are from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.

- The photo of New Mexico Senator and later U.S. Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall is from Wikipedia.

- The April 1928 Time cover photo of Harry Sinclair is from bidstart.com. Used with thanks.