- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Right Choice, Wrong Reasons: Wyoming Women Win ...

Right Choice, Wrong Reasons: Wyoming Women Win the Right to Vote

Thanks to an uneducated Virginian who had no use for black people, Wyoming Territory became the first government in the world to guarantee women the right to vote. No one person could have done such a thing by himself, of course. A territorial legislature, made up entirely of men, had to be persuaded that votes for women were a good idea.

The most interesting of all those men may have been the one who introduced the bill. He was a saloonkeeper from South Pass City, a frontier mining town nearly as big as Cheyenne at the time. William Bright never went to school. Somewhere along the way, he learned to read, write, and do math, though when he was an adult he could never remember quite where or when that was. He grew up in Virginia, a southern state, but served in the Union Army all through the Civil War.

(Bright was born in Alexandria, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., about 1827, at a time when Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia. Alexandria was ceded back to Virginia in 1846. In 1850, Bright was working as a bricklayer in Washington, U.S. Census records show, and by 1860 was serving with the D.C. police. His contemporaries, however, referred to him as a Virginian by origin, and most scholars since have followed their lead.)

After the war, he and his wife, Julia, 13 or 14 years younger than he was, moved to Salt Lake City. Gold was discovered in 1867 near where the old Oregon Trail crossed South Pass, and a gold rush started. William Bright moved to South Pass City that summer, hoping, like everyone else in town, to strike it rich.

He staked a lot of mining claims, and then made good money selling the claims as more and more miners flocked to the gullies and gulches around South Pass. In the spring of 1868, Julia Bright and their baby son, William Jr. moved from Salt Lake City to join the boy’s father.

New rights for ex-slaves

That was a presidential election year, and William Bright was a Democrat. During the Civil War, northern Democrats were uncertain that the killing was worth the cost. Many would have preferred some kind of compromise with the South instead of the pursuit of the fight to the bloody end. After the war, Democrats continued to oppose some of the most important changes the war had brought about. In particular, they opposed full citizenship and voting rights for black people—both the recently freed slaves and northern blacks who had been more or less free already.

Congress, controlled by the Republicans, soon passed the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution. The 14th guaranteed that the former slaves would be citizens, protected by the law like anyone else. The 15th Amendment guaranteed that no people could be denied the right to vote based on their color or on the fact that they had once been slaves. These two amendments were soon ratified—that is, approved by the states—and became law.

In May 1868, Democrats in South Pass City called a meeting to choose a person to travel to the national Democratic Convention, where the party would choose its candidate for president. William Bright was one of 17 men who signed a notice in the newspaper calling people to come to the meeting. Only strong Democrats should attend, the notice warned—men who opposed votes for black people and opposed the so-called Radical Republicans who were running Congress. Bright chaired the meeting. That fact gives us a glimpse of his political feelings—and probably his racial ones.

The next year, Bright opened a saloon on South Pass City’s busiest corner. By then, the mines were playing out, and the town was shrinking. Bright must have known this, and might have guessed a saloon would not have a prosperous future in a town like that. But running a saloon was a way to become well known in a community made up almost entirely of miners without wives or families. Because being well known helps a lot when a person runs for office, Bright may have been thinking of going into politics.

Wyoming’s first legislature

In the fall of 1868, the popular Union Army Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, a Republican, was elected president. Not surprisingly, Grant soon appointed Republicans to run the brand-new Wyoming Territory. These included the governor, John Campbell; Campbell’s second in command, Secretary Edward Lee; and Attorney General Joseph A. Carey, the top government lawyer in the state. They arrived in May 1869. Not long afterward, Carey issued an official legal opinion that no one in Wyoming could be denied the right to vote based on race.

A territory-wide election was held in early September. Many Democrats saw Carey’s opinion as a move to make sure Wyoming’s black people voted Republican, and they were probably right. But to the Republican Gov. Campbell’s surprise and embarrassment, only Democrats were elected. The territory’s new delegate to Congress was a Democrat, and all 22 members of the new territorial legislature were Democrats, too.

One of these was William Bright. The South Pass City saloonkeeper won a seat in the Council, or upper house of the Legislature—essentially a senate. He must have been well liked, because the other councilors elected him president of the Council, which meant he would get to run the meetings and decide which bills got voted on, and when.

Women’s rights in the air

The Legislature met in October 1869 in Cheyenne. All those Democrats seem to have had it on their mind not to protect black people’s rights, like the Republicans wanted to do, but to protect women’s rights. They passed a resolution allowing women to sit inside the special space where the lawmakers sat. They passed a law guaranteeing that teachers—most of whom were women—would be paid the same whether they were men or women. And they passed a bill guaranteeing married women property rights separate from their husbands.

The idea that women deserved the same rights as men had been growing steadily in the United States since the 1840s. For a long time, many people who supported the abolition of slavery also supported women’s rights. Both feelings were strong in the Republican Party before the Civil War. But after the war, Republicans felt they had to do all they could to make sure the freed slaves got the right to vote and were able to keep it. So, the Republicans put women’s rights on the back burner. Some women were furious about this and felt betrayed by the party.

In 1854, meanwhile, the legislature in Washington Territory tried and failed to give women the right to vote. Nebraska Territory did the same in 1856. In Congress, a senator introduced a bill after the Civil War to give women in all the territories the right to vote. This failed, too, as did bills in 1868 that would have amended the U.S. Constitution to give all women in the United States and territories the right to vote. Early in 1869, Dakota Territory came within one vote of passing a so-called woman suffrage bill. The idea was not new in American politics. Many of Wyoming’s legislators came from states or territories where the question had been discussed often.

Bright’s bill

Maybe it’s not so surprising, then, that William Bright, fairly late in the legislative session, introduced a bill to give Wyoming women the right to vote. Unfortunately, no record was kept then (or now) of what Wyoming lawmakers actually said while they were debating bills. But what was on Bright’s mind and on the other legislators’ minds can be gleaned from newspaper articles and from people’s memories reported years later.

First, lawmakers wanted to get Wyoming some good publicity, so that more settlers would come to the territory. With the railroad built, and the gold mines at South Pass producing less and less gold, it seemed as though more people were leaving than coming in. Positive news stories published throughout the nation, legislators thought, might reverse the trend.

The lawmakers especially hoped the news would bring more women. There were six adult men in the Territory for every adult woman, and there were very few children. American Indians were not counted in these numbers, but Chinese workers—most of whom had come to work on the railroad—and black people were counted.

Second, these Democrats in the legislature hoped that once these women came to Wyoming, they would continue to vote for the party that had given them the vote in the first place.

Third, the Democrats in the Legislature wanted to make John Campbell, the Republican governor, look bad. If they passed the bill, many assumed, Campbell would veto it. Here he was, their thinking went, a member of the party that supposedly championed the voting rights of the ex-slaves, but given a chance to extend the vote to women he wouldn’t be able to bring himself to do it. The idea was too new, too different. The Democrats enjoyed the possibility of embarrassing him.

A racial argument

Fourth, many of the legislators believed strongly that if blacks and Chinese were to have the vote, then women—especially white women—should have it, too. The following spring, a Cheyenne newspaper reported this as “the clincher” argument. “Damn it,” an unnamed legislator supposedly said, “if you are going to let the niggers and the pigtails [the Chinese] vote, we will ring in the women, too.”

William Bright, uneducated saloon-keeper, stalwart Democrat, ex-Virginian, Union Army veteran, president of the Council and the man who had introduced the bill to give women the vote, was one of the main backers of this argument. Some stories attribute it to his young wife, Julia Bright.

Image

Stories also circulated in later years that the whole thing had been a joke, that the lawmakers were mostly kidding and the entire idea went further than anyone had expected. That may be partly, or slightly true, but it goes against the fact that they spent a great deal of time debating the issue—hardly something the legislators would have done if they hadn’t taken it seriously.

And finally, some lawmakers wanted to give the vote to women simply because it was the right thing to do. Bright was among this number, as well.

The bill’s bumpy ride

The bill passed the Council, where Bright had first introduced it, six votes to two. In the House, lawmakers tried and failed to attach various amendments. Some of these were attempts to make the bill so unattractive to the other legislators that it would fail. One such amendment, which did fail, would have extended the vote to “all colored women and squaws.”

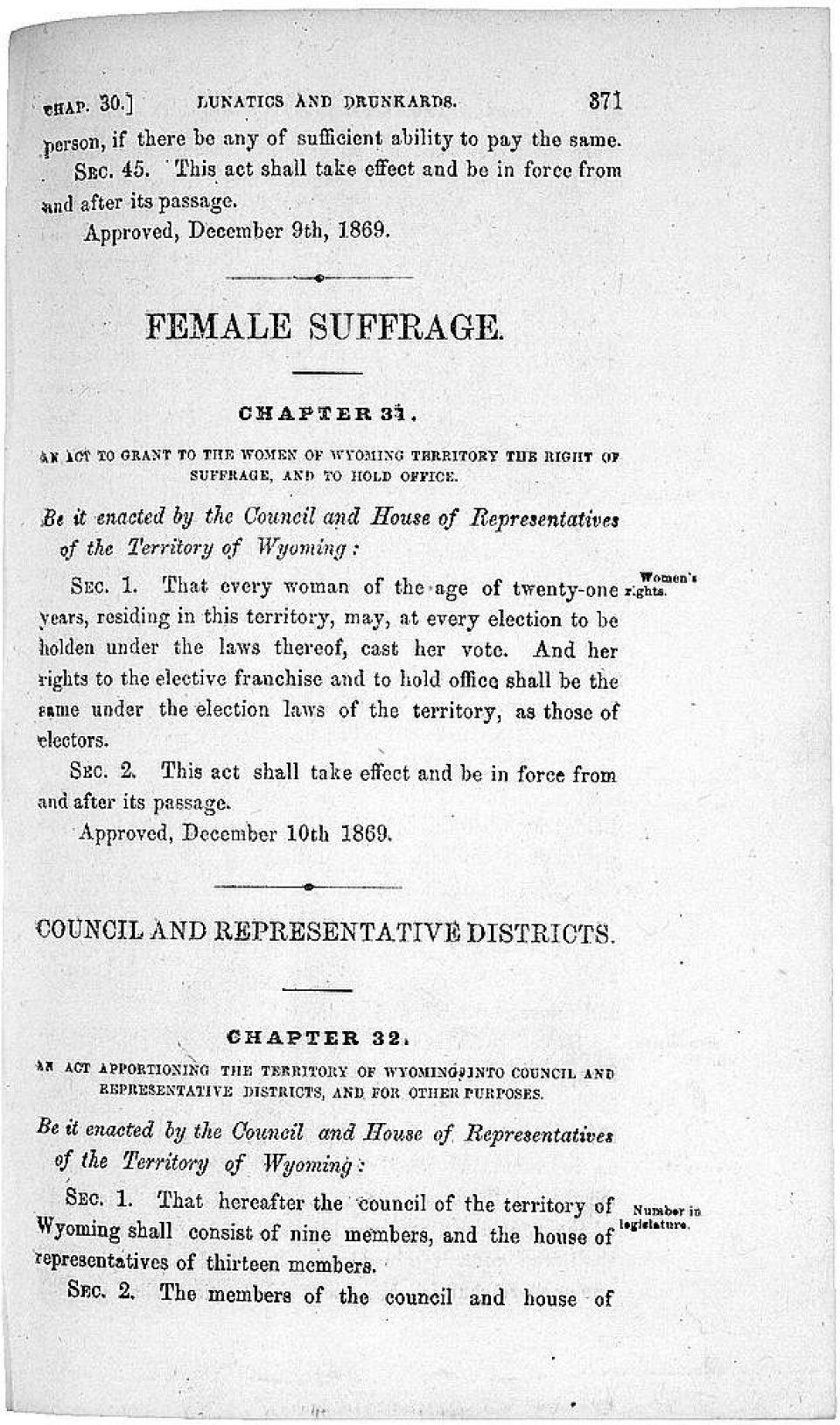

The House did pass an amendment to raise the voting age for women from 18 to 21. The House then passed the woman suffrage bill seven votes to four, with one abstention. Governor Campbell took several days deciding what to do. He finally signed the bill into law Dec. 10, 1869.

Esther Morris, first woman officeholder

Later that month, back in South Pass City, Bright welcomed a couple of visitors into his home. These were John Morris and his wife, Esther Hobart Morris. John Morris later wrote a letter about the visit to The Revolution, a national magazine that championed women’s rights. Bright was glad to see the Morrises, John Morris wrote, as they had come to congratulate him and were among a very few people in South Pass City who approved votes for women.

Early in 1870, Esther Morris was appointed justice of the peace, a kind of judge, becoming the first woman ever to hold a public office. In 1870 and 1871, Amalia Post and other women served on juries in Laramie. In September 1870, women throughout the Territory finally got the chance to vote in Wyoming’s second election.

As many as 1,000 women appear to have gone to the polls. To the disgust of the Democrats who had given them the vote, a great many voted Republican. A Republican was elected territorial representative to Congress. And the following year, 1871, a few Republicans were elected to the legislature.

A repeal attempt

The new legislature decided votes for women weren’t such a good idea after all, however, and passed a bill to repeal the 1869 law. To his credit, Gov. Campbell vetoed the repeal. The House came up with the two-thirds vote necessary to override his veto, but the Council fell one vote short. That left the new law standing, and it was never challenged again. All women in the United States did not win the right to vote for nearly 50 more years.

Aftermath

Meanwhile, Bright’s saloon business went bankrupt, and he and his family moved to Denver. Many years later, in 1902, he was noticed in the audience at a national convention on women’s rights. Asked to speak about what had happened in Wyoming, he stood up and said the bill was not introduced “in fun.” He added that he supported the idea because he believed “his wife was as good as any man and better than convicts and idiots,” the Women’s Tribune reported. If he mentioned black people at this point, or used a more derogatory term, the paper did not repeat it.

Perhaps the whole story of Wyoming’s choice to give women the vote shows that the right thing sometimes happens for a large, strange mix of reasons, most of them wrong. Or as John Morris wrote to The Revolution after his and Esther’s visit to William Bright, “It is a fact that all great reforms take place, not where they are most needed, but in places where opposition is weakest; and then they spread … .”

Resources

Primary Sources

- Cheyenne Leader, 1867-1869, accessed Sept. 27, 2013, via Wyoming Newspaper project at http://wyonewspapers.org/. The article mentioning “niggers and pigtails” was published April 28, 1870, and cited in Fleming, listed below.

Secondary Sources

- Ewig, Rick. “Did She Do That?: Examining Esther Morris’ Role in the Passage of the Suffrage Act.” Annals of Wyoming 78, no. 1 (winter 2006): 28-34. The story that Esther Hobart Morris gave a tea party in South Pass City before the 1869 election to extract a promise from Bright and his Republican opponent, Herman Nickerson, that whichever was elected would introduce a woman suffrage bill, was invented by Nickerson in 1919. Ewig examines the story’s roots and its remarkable staying power.

- Fleming, Sidney Howell. “Solving the Jigsaw Puzzle: One Suffrage Story at a Time.” Annals of Wyoming 62, no. 1 (spring, 1990): 22-65. Accessed Sept. 27, 2013, at http://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom621231990wyom. This article is particularly good at placing events in Wyoming in the context of larger movements for women’s rights in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Larson, T.A., History of Wyoming. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 79-94. Larson’s scholarship on the coming of woman suffrage to Wyoming is some of his best work, especially his modest debunking of the Esther Hobart Morris myth.

- _________. “Petticoats at the Polls: Woman Suffrage in Territorial Wyoming.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 44, no. 2: 74-79.

- Massie, Michael A. “Reform is Where You Find It: The Roots of Woman Suffrage in Wyoming.” Annals of Wyoming 62, no. 1 (spring 1990), 2-22. Accessed Sept. 27, 2013, at http://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom621231990wyom. This may be the best single article about woman suffrage in Wyoming. It contains especially good information about William Bright, South Pass City, the roots of the Esther Morris tea-party story and the personalities and politics leading to the bill’s passage.

- Simon, John Y. “Ulysses S. Grant.” Accessed Sept. 27, 2013, at http://www.presidentprofiles.com/Grant-Eisenhower/Grant-Ulysses-S.html. For more detail on what was going on nationally at the time the Wyoming Territorial Legislature voted for woman suffrage, see the sections on the election of 1868 and Reconstruction in this readable profile of Ulysses S. Grant.

For further reading and resreach

- Anderson, Jessica. " Overlooked No More: She Followed a Trail to Wyoming. Then She Blazed One." New York Times. Accessed May 26, 2018 at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/23/obituaries/overlooked-esther-morris.h.... A biographical sketch of Esther Hobart Morris.

- “The 19th Amendment And The Women’s Suffrage Movement.” Parker/Waichman LLP, accessed Jan. 6, 2021 at https://www.yourlawyer.com/library/19th-amendment-womens-suffrage-movement/. A Web page packed with information and useful links.

Illustrations

- The photo of William Bright is from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.

- The photos of South Pass City and of the Rollins House, downtown Cheyenne, are by William Henry Jackson, from the U.S. Geological Survey photo library. Used with thanks.

- The image of women voting in Cheyenne ran in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Nov. 24, 1888 and is now housed at the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The image of the page from the Wyoming Territory book of statutes woman showing the woman suffrage law is also from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Esther Hobart Morris is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with thanks.