- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Making a Home In Empire, Wyo.

Making a Home in Empire, Wyo.

The plains of Wyoming and Nebraska are dotted with old cemeteries hidden in hay meadows or on vacant plots between county roads slicing the countryside in perfect, straight lines. Interred in the graves are thousands of settlers who came west at the turn of the 20th century to scratch a living in a wilderness of grass and sagebrush.

Many of the farming communities that sustained the cemeteries have not survived. Farmhouses, churches and other buildings crumbled into the soil or were scavenged by people for other purposes. The graves are often the only remains of once vibrant agricultural towns.

Roughly ten miles northeast of Torrington, Wyo., and a mile over the state line in Nebraska, lies the cemetery for the abandoned Sheep Creek Presbyterian Church. The cemetery served the community of Empire, Wyoming, founded in 1908 by African-American families who came from Nebraska to build a racially self-sufficient, politically autonomous community in the Equality State.

Empire lasted less than two decades, however, and disappeared from the landscape by the mid-1920s. Drought, together with the negative farm economics of the early 1920s and the racial animosity of their neighbors eventually forced Empire’s citizens to abandon the town. The 1913 death in police custody of a member of one of Empire’s prominent families—historian Todd Guenther calls it a lynching—was only the worst incident in a string of race-based difficulties.

African-American community building in the West

Empire’s story opens with the social upheaval that followed the American Civil War. The war left the South in ruins, and the post-war Reconstruction Era was marred by poverty and racial upheaval. Many African-Americans fled these conditions to seek new opportunities on the western plains recently opened to settlement by the federal Homestead Act of 1862 and related state and federal land laws.

In the 1870s, more than 25,000 African Americans flooded into Kansas, encouraged at least in part by Kansas’ abolitionist sympathies stretching back to before the Civil War. In 1859, Kansas had been the first state in the region to enact a constitution that declared its land open to settlers regardless of their race. The black immigrants to Kansas came to be known as “Exodusters.” The Exoduster movement eventually spread beyond Kansas to Oklahoma, the Dakotas, Colorado and Wyoming.[1]

Many of the Exoduster settlements were communal efforts organized by African-American emigration agencies. Leaders of the Exoduster movement believed that the only way for African Americans to achieve political rights after the Civil War was through the formation of autonomous, economically self-sufficient communities on the western plains.

In the 1890s Edward P. McCabe, a black politician from New York, founded the community of Langston City on newly opened land in Oklahoma Territory. McCabe echoed the sentiment of the Exodusters when he wrote in 1892 that “Langston City is a Negro City, and we are proud of that fact. Her city officers are all colored. Her teachers are colored. Her public schools furnish thorough educational advantages to nearly two hundred colored children.”[2]

An African-American community in Wyoming

At the dawn of the 20th century, Wyoming seemed an unlikely place for an African-American community. African-Americans were a small, isolated minority in a sea of whiteness. The Cheyenne State Leader reported on June 13, 1911 that only 65 out of 10,915 farms in the state were owned by “negro and other non-white farmers.” When the Exodusters first headed west in the 1870s, Wyoming was perceived as a vast desert—a rugged, inhospitable frontier outpost dominated by cattle barons and not suitable for farmers.

In the first decade of the 20th century, however, Wyoming experienced a homesteading boom. The landscape of eastern Wyoming began to reflect the yeoman farmer rather than the cowboy. The federal government worked to turn the arid land of the west into a Garden of Eden through extensive irrigation projects organized by the new U.S. Reclamation Service formed in 1902.

Homesteaders were also encouraged by the 1909 Enlarged Homestead Act, which doubled the size of available allotments from 160 to 320 acres. Agriculturalists at the time believed that so-called dryland farming had the potential to turn prairie dust into productive soil through methods like deep plowing, crop rotation, and the use of drought resistant crops.[3]

In the early 1900s, homesteaders in the region appeared to embody the Jeffersonian ideal of a democracy of small landholders. An article in the Torrington Telegram boasted on January 2, 1908 that the land around Torrington was “suitable for the raising of all kinds of fruits, grains and vegetables,” by “active, business-like intelligent people, who maintain high ideals and strive to measure up to them.”

Life in Empire

The Jeffersonian ideal of the American yeoman farmer initially only extended to white men. Yet in the 20th century, descendants of slavery succeeded in embodying Jefferson’s image of the archetypal American in the small Wyoming community of Empire.

Empire was founded in 1908 by Charles Speese and his new bride, Rosetta. Three of Charles’ brothers–John, Joseph and Radford–and their families formed the nucleus of the new settlement.

The Speeses were joined by two branches of the Taylor family headed by Otis and Baseman. In 1911 Russell Taylor, an ordained Presbyterian minister, arrived in Empire with his wife, ten children and mother-in-law, and quickly became the community’s leader.

The Speeses and Taylors had come from Nebraska. Charles Speese’s parents Susan and Moses were originally born into slavery in North Carolina and moved to Nebraska in the 1870s at the height of the Exoduster movement. By 1908, the Speese family had managed to accumulate a considerable estate. According to the Torrington Telegram of May 14, 1908, the Speese brothers had inherited $10,000 from their uncle, Josiah Webb.

The brothers pooled the inheritance with proceeds from the sale of their land in Nebraska and purchased hundreds of acres near Torrington. By 1912, Empire had grown into a full-service farming community with its own school, post office and Presbyterian church.

The town sat above the well-watered North Platte River Valley on arid tableland that was not irrigated. Farmers in Empire, therefore, had to depend on dryland farming techniques. The Torrington Telegram reported on October 12, 1911 that Joseph Speese, with his knowledge of dryland farming methods, “raised more Irish potatoes than many of the farmers under irrigation.”

Potatoes were prominent in Empire, but Joseph Speese grew a wide variety of crops. The Torrington Telegram, on September 19, 1912, noted he won first-place prizes at the county fair for sweet corn, popcorn, potatoes, millet, cucumbers, muskmelon and field peas. Apparently, he had turned his corner of the Wyoming desert into a garden.

The push for a separate school

Within a year of settling in eastern Wyoming, the residents of Empire made a successful bid to the county school board to build their own school.[4] Clearly, Empire residents valued education highly; several had advanced degrees. Russell Taylor possessed a divinity degree from Bellevue College in Omaha, Neb.[5] John Speese earned a law degree at Wesleyan University in Salina, Kansas—a “remarkable” achievement for a “colored man” of his time, the Torrington Telegram would note in his February 1914 obituary.

In the early 20th century, education in Wyoming was legally segregated. The state’s school code stipulated that if a school district contained more than fifteen non-white students, the district could build separate educational facilities for them.[6]

Russell Taylor used the segregation law to advocate for an independent school for African-American children in Empire—free from the domination of the all-white school board in Torrington. Taylor believed that African-American children had the right to learn from a role model who belonged to their race.

Race relations in a troubled time

When the Speeses and Taylors arrived in Wyoming, race relations in America were at rock bottom. Jim Crow and the vigilante justice of the Ku Klux Klan ruled the lives of African-Americans. Thousands of African-American men, women, and children were lynched by white mobs in the United States in the first half of the 20th century. African-American veterans who returned home after World War I demanded greater equality from the country they had fought for. The white majority reacted violently to the unrest, and race riots erupted in cities across the country in 1919 and 1920.

The Equality State did not escape this turmoil. At least five African-American men were lynched by white mobs in Wyoming between 1904 and 1920.[7] State laws upheld segregation and banned miscegenation. Russell Taylor wrote numerous letters to the editor of local papers stating that he and other African-American citizens in Empire were often denied service and lodging at restaurants and hotels in Torrington.[8]

The state’s newspapers, the main conduits of information in a pre-digital age, de-humanized African Americans through racist advertisements and degrading cartoons. As racial violence swept the nation, the Wyoming State Tribune, for example, announced on July 22, 1919 that “law and order” around Cheyenne would be maintained by a “secret vigilante committee” made up “prominent men” from Cheyenne. The paper claimed the anonymous committee would aim its efforts at automobile thieves. But it hinted that committee members might move in “other directions” as well—much, it said, as vigilantes had moved against Cattle Kate 30 years earlier. “The Ku Klux Klan is with us!” reads one of the headlines on the story.

A death in police custody

On November 6, 1913, Russell Taylor’s brother Baseman died in what appears to have been a case of police brutality in Torrington. According to the Torrington Telegram, Baseman Taylor was arrested by Sheriff Michael A. Hayes for vandalizing a bank door in town. Taylor was judged incompetent by a hastily convened “insanity board” and was placed in a hotel room until he could be taken to the State Hospital in Evanston. On November 6, after three days in custody, the Telegram reported that Baseman died in the hotel due to a “pain in his head.”

Baseman Taylor’s death “was a lynching, an illegal killing by a group acting under the pretext of serving justice,” writes historian Todd Guenther, history professor at Central Wyoming College, who has written extensively on lynchings and life among African Americans in early Wyoming.[9]

The following year, Russell Taylor filed a wrongful death suit on behalf of his brother against the sheriff and deputies. The lawsuit’s depositions tell a different story from the one published by the papers.

Witnesses reported that Sheriff Hayes had responded to rumors of a “crazy negro” wandering town that day, and gathered a posse to arrest him. Baseman Taylor offered no resistance when he was apprehended by the posse, but the witnesses stated that, after he had been handcuffed to be searched, he was thrown violently to the ground. Two witnesses stated that Taylor injured his head during the arrest.

Over the next three days, the sheriff and several deputies kept Taylor shackled hand and foot in the hotel room. Witnesses in the wrongful death suit stated that Baseman was repeatedly beaten and choked by the sheriff and his deputies while he was in custody and died as a result of the abuse on the evening of November 6.

The witnesses, H.N. Carmichael and Abner Lloyd, were laborers from Colorado who were working on the new Goshen County Courthouse and were staying at the Torrington hotel where Baseman Taylor was being held. They said they watched Taylor’s torture in the hotel room night after night after they returned from work, and later travelled from their homes in Colorado to Torrington to testify on behalf of Taylor in 1914. Russell Taylor’s suit was later thrown out by District Court Judge William C. Mentzer in Torrington for lack of evidence.

Russell Taylor, activist

The settlers in Empire found a voice to fight back against racism through the leadership of Russell Taylor. Taylor was active in his role as an educator and spiritual leader, and advocated for his people both at local political events and at state and national conferences of the Presbyterian Church.

Taylor taught at Empire’s public school, and worked to maintain control over his students’ education. In 1914, for example, he appeared at a Goshen County school board meeting to protest the board’s hiring of a white teacher who lacked qualifications to teach at the Empire school. Taylor wrote in the Goshen County Journal on December 3, 1914, that due to the white teacher’s lack of a certificate, “she has been unable to properly control the school or do the work therein.” Taylor remained in charge of the school at least until 1916 when he was listed as Empire’s sole teacher in the Goshen County Journal on November 2 of that year.

He also wrote numerous editorials to the state and local press. In an era when speaking out against the status quo of white dominance was dangerous for African-Americans, Taylor refused to have his voice silenced. He always affixed his name to his letters, unlike many letter writers who encouraged racism.

On December 19, 1918, Taylor wrote a particularly impassioned protest against the lynching of Joel Woodson, an African-American man, by a white mob of more than five hundred in Green River, Wyo.

“It is believed that if Woodson could have told his story,” Taylor wrote, “the state whose motto is equal rights before the law would not have been again disgraced by another terrible lynching. Five hundred men would not be guilty of murder as they now are, though the law seems to take no cognizance of the fact.”

The end of Empire

According to the 1910 federal census, there were 36 African-Americans living in Empire that year, all members of the various branches of the Speese and Taylor families. In 1911, after Russell Taylor arrived with his wife, ten children, and his mother-in-law, and the African-American population rose to 49. However, the 1920 federal census showed only 23 African Americans living in Empire. By 1930, there were only four African Americans living in all of Goshen County out of a population of more than 11,000. By the late 1920s, Empire had vanished.

Economics provides one explanation for the community’s demise. America experienced a serious agricultural recession after World War I when agricultural prices, inflated by the war, took a nosedive in 1919. A bad drought in Wyoming that year made things far worse. Many farmers in Wyoming were forced into foreclosure when the agricultural bubble burst.[10] Banks failed in Wyoming throughout the 1920s.

Despite the 1919 bust, homesteaders continued to flood into Wyoming during the 1920s. Many new settlers took advantage of the 1916 Stock Raising Homestead Act that opened up non-irrigated land for cattle grazing and doubled allotment sizes to 640 acres Thousands of farmers flocked to marginal lands to try their hand at dryland farming.[11] Many white settlers managed to weather the bust and remain in Goshen County.

Yet all of the county’s African-American homesteaders had left by 1930. Isolation and racism had taken its toll on the black settlers who tried to make a new life in Empire. The people of Empire lacked an organized community or social safety net outside the confines of their little town. Fears of racism, harassment and death must have been constant in their lives.

(Editors’ note: WyoHistory.org thanks Beth King and the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office for supporting intern Robert Galbreath’s work, including this article, during the summer of 2016.

[1] Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West 1528-1990 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), 136, 144, 152.

[2] Ibid. 144-146.

[3] Michael Cassity, Wyoming Will Be Your New Home: Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming, 1860-1960 (Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office Planning and Historic Context Development Program, 2011) 89, 109-110, 147, 150.

[4] Torrington Telegram, July 15, 1909.

[5] Torrington Telegram, October 12, 1911.

[6] Clayton B. Fraser et. al., Places of Learning: Historical Context of Schools in Wyoming (Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office Planning and Historic Context Development Program, 2010), 42.

[7] Todd Guenther, “The List of Good Negroes: African-American Lynchings in the Equality State,” Annals of Wyoming (2009), 2-33.

[8] Torrington Telegram, Nov. 26, 1914, Goshen County Journal Nov. 19, 1914, Wyoming State Tribune, Dec. 19, 1918.

[9] Todd Guenther, “The Empire Builders: An African American Odyssey in Nebraska and Wyoming.” Nebraska History 89 (2008): 192.

[10] Cassity, 208-211.

[11] Ibid. 227.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “B. Cunningham of Empire,” Torrington Telegram, May 14, 1908, 1.

- “Death of Baseman Taylor,” Torrington Telegram, November 6, 1913, 5.

- “J.S. Speese and Russell Taylor,” Goshen County Journal, December 3, 1914, 1.

- “Joe Speese, First,” Torrington Telegram, September 19, 1912, 4.

- “Joe Speese Raised,” Torrington Telegram, October 12, 1911, 4.

- “Notice for Sealed Bids,” Torrington Telegram, July 15, 1909, 1.

- “Obituary of J.W. Speese,” Torrington Telegram, February 26, 1914, 8.

- “Reverend Russell Taylor of Newmarket,” Torrington Telegram, October 12, 1911, 4.

- “School Officers and Teachers of Goshen County,” Goshen County Journal, November 2, 1916, 3.

- “Some of the Patrons,” Torrington Telegram, September 15, 1910, 4.

- Taylor, Russell, “The Green River Lynching,” Wyoming State Tribune, December 19, 1918, 2.

- Taylor, Russell, “Letter to the Editor,” Goshen County Journal, November 19, 1914, 1.

- Taylor, Russell, “Letter to the Editor,” Torrington Telegram, November 26, 1914, 4.

- “Torrington,” Torrington Telegram, January 2, 1908, 4.

- “Would Lynch Auto Thieves in Cheyenne,” Wyoming State Tribune, July 22, 1919, 1.

- “Wyoming Grows in Importance as an Agricultural State,” Cheyenne State Leader, June 13, 1911, 5.

- Russel [sic] Taylor, Administrator vs. Michael A. Hayes and U.S. Fidelity and Guaranty, Goshen County Probate no. 1-10, 1914. Accessed June 19, 2016, Wyoming State Archives.

Secondary Sources

- Bureau of Land Management. “Split Estate Minerals Ownership.” Accessed July 25, 2016 at http://www.blm.gov/wy/st/en/programs/mineral_resources/split-estate.html.

- Cassity, Michael. Wyoming Will Be Your New Home: Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming, 1860-1960. Cheyenne, WY: Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, 2011.

- Fraser, Clayton B., Mary M. Humstone, and Rheba Massey. Places of Learning: Historical Context of Schools in Wyoming. Cheyenne, WY: State Historic Preservation Office, 2010.

- Guenther, Todd. “The List of Good Negroes: African American Lynchings in the EqualityState.” Annals of Wyoming (2009): 2-33.

- ____________. “The Empire Builders: An African American Odyssey in Nebraska andWyoming.” Nebraska History 89 (2008): 176-200. Accessed Aug. 31, 2016 from: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH2008Empire_Builders.pdf

- Kansas Historical Society. “African Americans in Kansas.” Kansapedia. Accessed July 25, 2016 at https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/african-americans-in-kansas/15123.

- Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998.

For further reading and research

Historian Todd Guenther, who teaches history and archeology at Central Wyoming College in Riverton, Wyo., has done extensive work on relations between whites and African-Americans in early 20th century Wyoming. His articles, “The List of Good Negroes” and “The Empire Builders,” cited fully above, offer important insights and are well-written, well-researched and well-sourced.

Illustrations

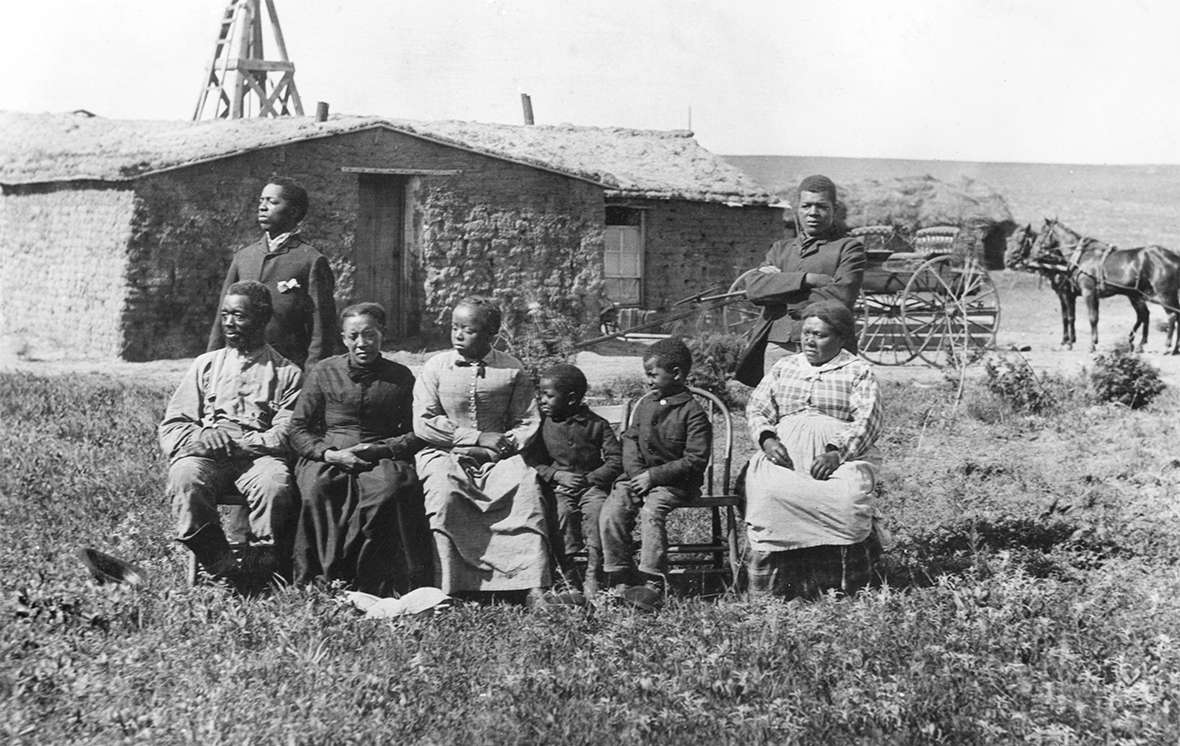

- The 1888 photo of the Speese family is from the photo collections at the Nebraska State Historical Society. Used with permission and thanks.

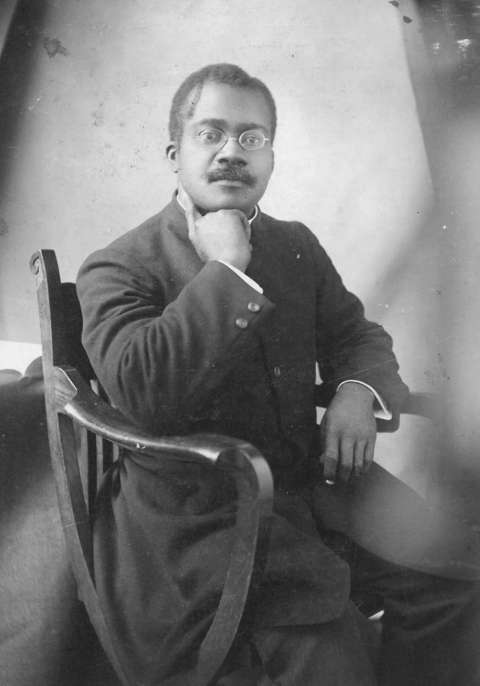

- The photo of Russell Taylor is from the Hastings College archives, Hastings, Neb. Used with permission and thanks.

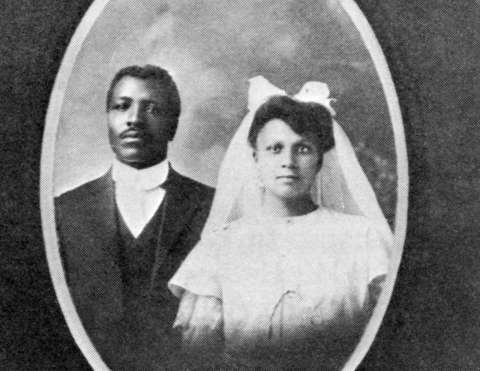

- The photo of Charles and Rosetta Speese is from Sod House Memories: A Treasury of Soddy Stories, Frances Jacobs Alberts, ed. Hastings, Neb.: Sod House Society, 1972. Used with thanks.

- The map fragment showing Torrington and surrounding towns and hamlets is from a larger map published by the Wyoming Public Service Commission in 1915, via Wyoming Places. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the dryland farming exhibit is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.