- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Bill Carlisle, Gentleman Bandit

Bill Carlisle, Gentleman Bandit

The story reads like a dime novel: A white-masked train robber succeeds in acquiring “donations” from Union Pacific passengers and, despite a massive manhunt, eludes capture. He robs again. After being caught, he escapes from prison, holds up another train, and is returned to the penitentiary. There, he meets a priest who helps him repent. The robber earns parole, marries, operates a restaurant, and writes a book about his experiences.

But this tale is not fiction. Bill Carlisle and the great rewards offered by the Union Pacific Railroad for his capture “dead or alive” were real. He committed three robberies in 1916 and a fourth in 1919 after his escape from the Wyoming State Penitentiary.

Carlisle, the youngest of five children, was born May 4, 1890, when his father, a carpenter and Civil War veteran, was 60 years old. His mother, twenty-three years younger, died nine months after Bill was born. Because their father was in ill health, the children stayed with relatives or in orphanages. Bill stayed at an orphanage in York, Penn., his mother’s hometown.

Following a brief circus stint in 1905, Carlisle eventually drifted to Denver, Colo., where, in late 1915, he purchased an imitation glass gun that he planned to fill with candy and send to a niece for a Christmas gift. With little money left, he tried to find work in the city to no avail, so he headed to Cheyenne, Wyo. His luck was no better there, and he “rode the ‘rods’” of trains, traveling west.

With only a nickel in his pocket and no job prospects, he decided a train robbery would fetch him enough money to survive through spring. In addition to the toy pistol, he carried a .32-caliber handgun.

“You couldn’t starve to death in Wyoming if you had a gun with which to shoot game,” he wrote later.

On February 9, 1916, Carlisle concealed himself between two train cars and then swung onto the rear of the Portland Rose, as it pulled away from the Green River, Wyo., station. During the holdup, which the brakeman thought was a joke until the robber fired a shot through the top of an upper berth, Carlisle returned the porter’s coins to make up for his lost tips and gave a silver dollar to a man to pay for his breakfast. He bowed to a woman who tried to get his gun. No one was injured. Carlisle, whose face was hidden under a white bandanna, leapt from the train about three miles from Rock Springs, Wyo. He landed and rolled near the moving wheels, so close that his glass gun shattered against the rails.

The gain from the robbery was only $52.35, but news of the “White Masked Bandit” spread quickly. The crime was the first of its type to occur in sixteen years.

The Union Pacific Railroad offered a $1,500 reward. A posse followed a wrong trail, and Carlisle eluded capture. He returned to Green River to buy a ticket to Wheatland, Wyo.

One of the men of the posse, Charley Irwin, at that time special agent for the Union Pacific, and who later became known for providing broncos for Cheyenne Frontier Days, stood near the window, visiting with the ticket agent and another man. The ticket agent told Irwin that a customer was behind him. Carlisle, nervous because he recognized Irwin, purchased his ticket and turned to leave. Irwin placed a hand on his shoulder. Carlisle looked back, fearing the worst. Irwin said, “You forgot your change.”

By early April, Carlisle was back in Cheyenne, determined to go to Alaska. He needed money, so he robbed the Overland Limited between Cheyenne and Laramie on April 4, 1916, receiving $506.07. The U. P. reward increased by $5,000, enough that even homesteaders, who knew that a $6,500 reward could pay their mortgages, joined the search.

Law enforcement officials, overwhelmed by the number of telegrams and tips received, overlooked a legitimate message from a person who saw Carlisle in the vicinity of the Cheyenne robbery. Meanwhile, Carlisle made his way to Douglas, Wyo. He joined a saloon card game, got lucky and doubled his money. He then traveled by train to Casper, Wyo.

Upon learning other men were landing in jail for his crimes, Carlisle sent a letter to the Denver Post, enclosing a watch chain snatched during one of the holdups. He signed the letter, “The White Masked Bandit,” stating he would rob another train somewhere west of Laramie so the unjustly accused men could be set free.

The bandit struck again on April 21, 1916. He gave the train’s guard the watch matching the chain that was earlier sent to the Denver newspaper. When he jumped from the train, about four miles east of Walcott, Wyo., $378.50 richer, he injured his right ankle and bruised his face.

Saratoga, Wyo., native E. W. Walck, Sr. recalls his mother, Edna Walck, telling him she remembered the day the transcontinental train stopped at Walcott, a very unusual circumstance. Edna taught school for a short time at Walcott when she was nineteen. She boarded at the small hotel located there. There were two regular trains at that time. The Portland Rose carried local passengers from Cheyenne to Rawlins and Rock Springs, and the San Francisco Limited traveled cross-country. Westbound, the Limited stopped at Walcott so news of the robbery could be telegraphed ahead.

Another posse was put together and this time, it succeeded. Carlisle was caught the next day about 12 miles north of Walcott. Carbon County Sheriff Rubie Rivera of Rawlins, Wyo., took the robber into custody. The reward was split between Rivera, who took $500, and the members of the posse. In his memoirs, Rivera said he dreaded other criminals more because Carlisle was “more like a kid showing off.” Passengers on the train were able to identify the bandit. On May 10, 1916, after a two-day jury trial, Carlisle was sentenced to life in prison.

In July 1919, his sentence was reduced to 50 years, but Carlisle wanted out. He escaped from the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Rawlins in November 1919 by hiding in a carton containing shirts made by the prisoners. On Nov. 19, 1919, he robbed a train near Rock River, Wyo. The passengers were mostly soldiers and sailors returning after World War I from military duty in France. Carlisle let them keep their money, saying, “I would have been over there with you had they let me go.”

He collected $86.40 from the others. When a young man aimed his gun at Carlisle, the bandit knocked it away. The gun discharged, injuring Carlisle’s hand.

Two weeks later, he was captured in a prospector’s cabin near Douglas where he was shot in the chest. Thirty-three days later, following surgery in Douglas, Carlisle was incarcerated again in Rawlins. Because the Union Pacific had spent about $15,000 hunting Carlisle in 1916, the company, this time, relied on the state to conduct the search.

Carlisle was imprisoned in Rawlins for 16 more years. While there, he met Reverend Gerard Schellinger, a local Catholic priest who helped the bandit go straight. Carlisle earned parole and was released on Jan. 8, 1936. Carlisle spent his first evening as a free man by eating dinner “with my best friend, Father Schellinger.”

Carlisle opened a cigar shop and newsstand in Kemmerer, Wyo., where Schellinger was posted. While recuperating from a ruptured appendix, Carlisle met Lillian Berquist, the superintendent of the local nursing home. They married on Dec. 23, 1936. Abandoning the cigar store, Carlisle moved to Laramie and worked at a filling station in Laramie for about a year. In 1937, the Saratoga Sun reported Carlisle leased Spring Creek Camp east of Laramie, planning to open “a lunchroom and a filling station” there.

E. W. Walck, Sr. recalls eating in the second story loft of Carlisle’s café as a college student in the 1940s in Laramie. Customers paid extra to take their meals upstairs. This building, Walck says, is located on Grand Avenue near 30th Street and currently houses a floral shop.

Kenneth Ostlind of Lewistown, Mont. and his friend Ottmar Grose worked briefly mopping and cleaning up at Carlisle’s establishment when they were University of Wyoming students in 1947-’48. Carlisle was generous enough to tell the young men to cook themselves a meal in his absence. But after he learned they’d helped themselves to the steaks in the cooler, Ostlind remembers, the old bandit fired them.

Some Carbon County residents also remember attending Carlisle’s book signings. The reformed robber’s autobiography was published in 1946. He dedicated the book to his sister, his wife, and to Schellinger, “friend of the later years, who taught me that often in failure there lies great success.”

Carlisle sold his Laramie business in 1956. After his wife died in 1962, he moved to Coatesville, Penn., where he lived with his niece. He died of cancer on June 19, 1964.

In June 2012, a Denver auction house sold an Iver Johnson .32-caliber revolver reportedly owned by Bill Carlisle and confiscated after the 1919 train robbery. In the same auction lot were several other items from the collection of George Carroll, who served as a U.S. marshal and as sheriff of Laramie County, Wyo. in the 1920s and 1930s.

Items sold at auction with the pistol included the original telegram warning trains to “keep a close lookout” because the No. 19 had been robbed near Medicine Bow, a poster offering a $1,000 reward for the bandit, a photo of Carroll and Carlisle, signed by both and taken in the mid-1950s, and an autographed, first-edition copy of Carlisle’s autobiography. The lot sold for $10,030 including the buyer’s premium.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Author’s interview. E. W. Walck, Sr. February 26, 2011.

- Carlisle, William L. Bill Carlisle, Lone Bandit: An Autobiography. Pasadena, Calif.: Trail’s End Publishing Company, 1946, pp. 10, 103, 104, 109, 111, 112, 127, 128, 133, 136, 143, 147, 152, 154, 156, 167, 168, 169, 172, 181, 182, 195.

- Author’s Note: Bill Carlisle visited with interviewer Robert H. Burns about his experiences, and the audio was converted into digital format 28 November 2006 by the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. The train robber, whose voice is confident and compelling, chuckled when he remembered Irwin’s failure to recognize him at the Green River ticket office. Listen to the interview at: http://digitalcollections.uwyo.edu:8180/luna/servlet/view/search?fullTextSearch=fullTextSearch&q=Bill+Carlisle&search=Search

- McCracken, Melissa, publicist for Lebel’s Old West Auction House, Denver. Email to author July 13, 2012.

- Rea, Tom. Interview with Kenneth Ostlind February 23, 2011.

- Wyoming Pioneers Oral History Project, American Heritage Center. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming, Access Number 300018, Box 1 Folder 9. http://digitalcollections.uwyo.edu, accessed February 26, 2011.

Secondary Sources

- Van Pelt, Lori. Dreamers and Schemers: Profiles from Carbon County, Wyoming’s Past. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press, 1999. pp. 142, 143, 145, 149, 151.

Illustrations

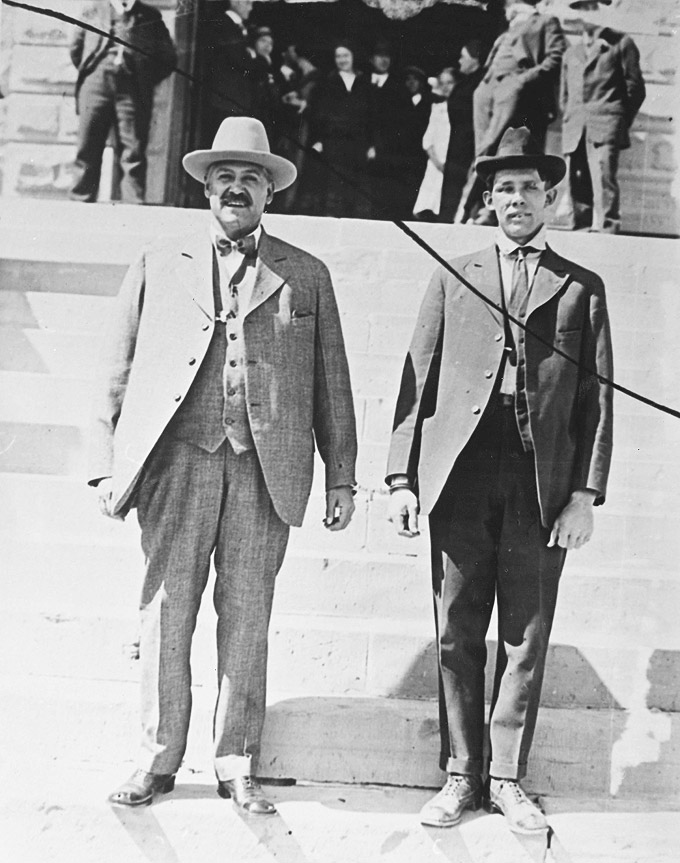

- The 1916 photo of Carbon County Sheriff Rubie Rivera, left, and Bill Carlisle on the steps of the Carbon County Courthouse in Rawlins is from the Carbon County Museum. Used with thanks.

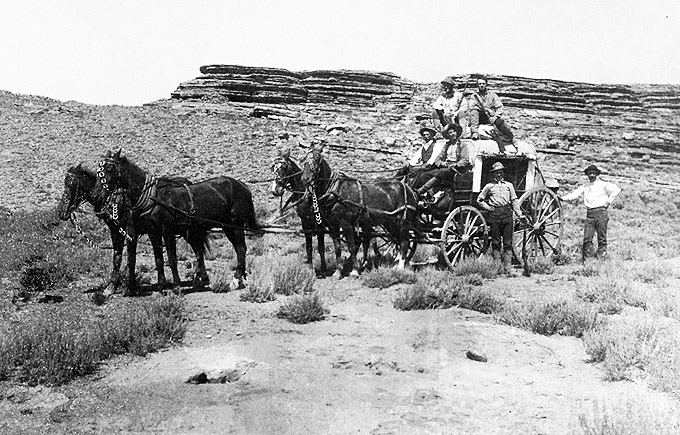

- The photo of the posse on the stagecoach is undated, but probably from the spring of 1916. Written on the back of the original are the words, “Hunting Bill Carlyle [sic], train robber.” It’s from the Jackson Collection, Hanna Basin Museum. Used with thanks.

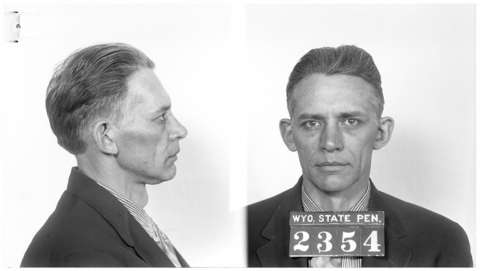

- Bill Carlisle's 1935 mugshot is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.