- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Killing Spree That Transfixed a Nation: Cha...

The Killing Spree that Transfixed a Nation: Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate, 1958

In late January 1958, newsmen from across the West jammed the Converse County Courthouse as crowds of curious teenagers gathered outside [1] hoping to glimpse the notorious killer, Charles Starkweather. Starkweather and his girlfriend, Caril Ann Fugate, had been captured earlier that day east [2] of Douglas, Wyo. “The curious made a bedlam of the sheriff’s office” while phone circuits overloaded and frustrated reporters scrambled to reach their editors. [3]

The capture, after a high-speed shoot-out through downtown Douglas, brought to an end a murderous rampage that had claimed eleven lives, counting a victim Starkweather had murdered two months earlier, and kept residents of Nebraska and the surrounding region in a state of panic for a full week.

A serial killer was loose for the first time in the television age and no one knew where or when he might strike next. The seemingly random nature of Starkweather’s victims–young and old, male and female, rich and poor, acquaintances and strangers–added to the terror. The killing spree, apparently triggered by parental disapproval of a teenage romance, had spiraled dangerously out of control.

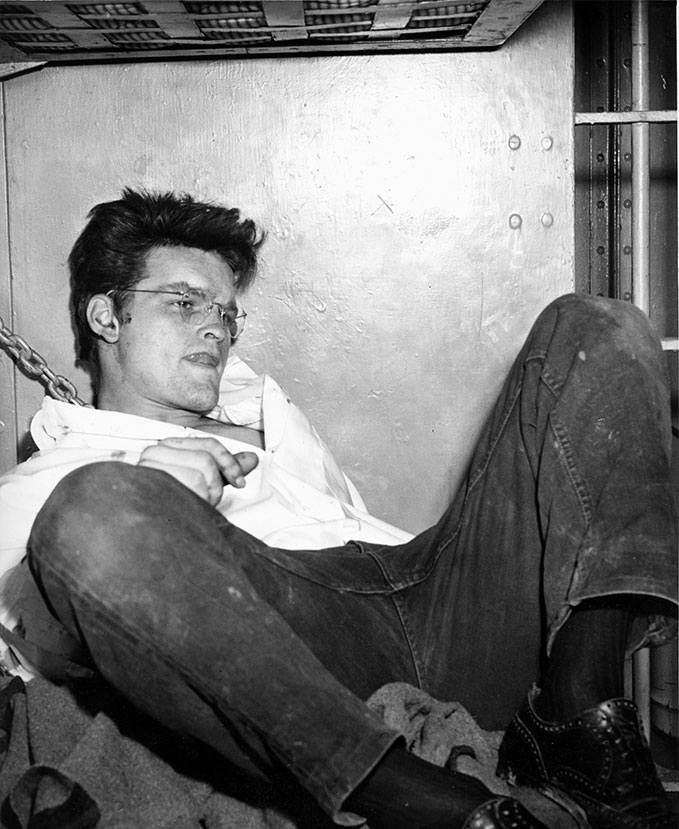

At 19 years old, Starkweather was “a swaggering good-for-nothing in blue jeans and a black motorcycle jacket.” A former garbage man known for yelling “go to hell” at strangers, [4] he was “stocky” and “well-built” but “small” at 5’5”. His normally red hair was now black with shoe polish. He wore rimless glasses [5] and black-and-white cowboy boots. [6] A James Dean wannabe, Starkweather was a rebel whose cause had devolved into instilling fear and dissipating his own smoldering rage.

After his capture, Starkweather told Lancaster County, Neb., Sheriff Merle Karnopp, “I always wanted to be a criminal but not this big a one.” [7] The “bandy-legged little gun toter,” [8] although “still defiant” [9] quickly confessed to the murders, even accepting responsibility for an additional victim: Robert Colvert, a 21-year-old gas station attendant recently discharged from the U.S. Navy, killed nearly two months earlier on Dec. 1, 1957. [10]

The role of Starkweather’s companion, 14-year-old Caril Fugate, would be more controversial. Fugate maintained that, after dating Starkweather for several months, she had broken up with him on Sunday, Jan. 19. She also claimed that on Tuesday, Jan. 21, when she got home from school, the house was empty except for Starkweather who said that her family was being held captive and would be killed if she didn’t cooperate. By that time, however, Fugate’s stepfather, Marion Bartlett, her mother, Velda Bartlett and Caril’s 2-year-old half sister Betty Jean Bartlett were probably already dead and their bodies stowed in outbuildings on the property.

For the next six days, the couple stayed in the family’s Lincoln, Neb., home. Caril turned away all visitors, including her sister, grandmother, brother-in-law and Charlie’s brother, telling them her family was sick. She even posted a warning on the door: “Stay a way. Every body is sick with the flue. Miss Bartlett,” with Miss Bartlett underlined twice. Caril said that was her attempt to signal trouble since the home’s only “Miss Bartlett” was her 2-year-old sister. [11]

But when Caril’s grandmother threatened to summon the police, Charlie fled with Caril, driving 15 miles southeast to Bennet, Neb., where his friend August Meyer lived. The unsuspecting Meyer opened his door to the pair, even offering his horses to free their car bogged down in mud. But, as the 70-year-old Meyer led them to the stables, Starkweather pulled his shotgun and killed the old man. He then beat the old man’s dog to death, breaking his shotgun in the process. According to Fugate, the unexpected brutality and Charlie’s earlier threats convinced her that her only option was to obey Starkweather.

Later that night, 17-year-old Robert Jensen of Bennet and his 16-year-old girlfriend Carol King offered Charlie and Caril a ride, becoming the next victims. Starkweather brutally raped King, shot both King and Jensen, and left their bodies in a storm cellar.

After returning to Lincoln in Jensen’s car, Starkweather and Fugate drove to an upper middle-class neighborhood looking for a place to hide. C. Lauer Ward, a prominent local businessman, was the unfortunate homeowner they selected for sanctuary. The next day, Ward; his wife, Clara; and Lillian Fencil, their maid, were found dead. [12]

Starkweather and Fugate used Ward’s 1956 Packard to flee Nebraska, heading west for Washington state where Charlie’s brother lived. Some ten hours later, near Douglas, Wyo., Starkweather decided to ditch the Packard because it was “too hot.” [13] Near the turnoff to Ayers Natural Bridge, he spotted Merle Collison, a 37-year-old shoe salesman from Great Falls, Mont., parked alongside the highway, napping. Starkweather approached the vehicle, tapped on the window to awaken Collison, then fired through the side window as he demanded Collison exit. When he didn’t, Starkweather fired several more rounds. [14]

At about the same time, Joe Sprinkle [15], a Sinclair oil landman from Casper, Wyo., came upon the scene. Seeing two cars parked on the highway, Sprinkle stopped to offer assistance. Starkweather asked Sprinkle to help him release the newfangled emergency brake on Collison’s car. By the time Sprinkle saw Collison’s body stuffed under the dashboard, Charlie had pulled a shotgun. Sprinkle realized “that if [Starkweather] won, I would be dead.” [16] Sprinkle, six feet tall, had a physical advantage over the smaller man and he began wrestling him for the gun. Although the gun “looked bigger every time I looked at it,” Sprinkle managed to wrench it away. [17]

As the two wrestled, Natrona County Deputy Sheriff William Romer drove up. When he got out to investigate, a young girl bolted from Collison’s car and ran towards Romer, screaming, “He’s going to kill me. He’s crazy. He just killed a man.” Meanwhile, Starkweather jumped into the Packard, turned it around and headed back towards Douglas. Romer, staying behind with Fugate who had identified the fleeing man as Starkweather, radioed for help. [18]

Douglas Police Chief Bob Ainslie and Converse County Sheriff Earl Heflin [19] immediately set up a roadblock near the Douglas city limits. When Starkweather blew through it, Ainslie gave chase at speeds exceeding 100 miles per hour through downtown Douglas, while Heflin fired out the window. East of town, a bullet finally shattered the Packard’s rear window, spraying glass. Starkweather suddenly slammed on the brakes and came to a screeching halt. After several tense moments, punctuated by additional demands and gunfire from the lawmen, Starkweather surrendered.

Asked why Charlie gave up, Heflin replied: “I guess he thought he was bleeding to death. That’s the kind of yellow SOB he is.” [20] Flying glass had nicked Starkweather’s ear lobe and right hand. He had also run out of ammunition for his remaining gun. Otherwise, he boasted, he would have shot it out: “They would never have caught me if I hadn’t stopped.” [21]

A day later, Starkweather appeared before Converse County Justice of the Peace Harry Wise to be charged with the first-degree murder of Merle Collison. [22]

However, Wyoming authorities, influenced by the post-capture statement of Gov. Milward Simpson, let it be known they would defer to Nebraska prosecutors. A staunch death-penalty opponent, Simpson had announced that, were Starkweather convicted and sentenced to death by a Wyoming jury, he would commute his sentence. “How can I dare try the man here, knowing the governor has come out against capital punishment?” Converse County Attorney William Dixon asked. Simultaneously, Simpson announced he would sign extradition papers “in a jiffy.” [23]

The next day, Jan. 31, 1958, Starkweather was returned to Nebraska. [24] His trial [25] began in May when his attorneys, contrary to Charlie’s wishes, offered an insanity defense. On May 23, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. Starkweather told his father, “If I want to make my atonement with God and be electrocuted, that’s my business.” [26] That same day, victim Carol King’s headstone was placed on her grave in the Bennet cemetery. [27] Starkweather was executed on June 25, 1959.

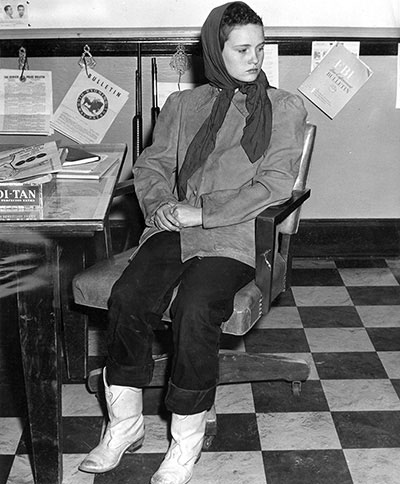

Fugate’s legal journey would be more complicated. After surrendering, Caril was “very nervous and upset” and “in a state of shock.” At the Douglas jail, she grew increasingly agitated until Converse County Sheriff Heflin had her sedated. [28] The next morning, she “cried and screamed for her mother,” wondering “why she couldn’t call her parents.” [29] Heflin told reporters, “I don’t think she knew that her folks were killed.” [30] On Friday, when Nebraska authorities confirmed her family was dead, Caril broke down, twisting tissues into tiny doll shapes. [31]

Starkweather initially identified his girlfriend “as a captive,” insisting “she didn’t have anything to do with it. She tried to get away a couple of times.” [32] Nevertheless, Nebraska prosecutors charged Caril with murder. [33] Her lawyers expected Wyoming law enforcement officers to bolster her case but, in “surprise testimony,” Natrona County Sheriff Romer testified that Caril had admitted to seeing her family killed, adding several credible details. [34]

Converse County Sheriff Heflin bolstered Romer’s assertion by claiming that, when arrested, Caril had clippings in her pocket related to her family’s murder. [35] Reconciling their trial testimony with contemporaneous newspaper accounts, [36] which won local reporters the Associated Press Managing Editor’s award and a Pulitzer nomination, is difficult. But with no one supporting her claims–Charlie had flipped and now claimed she was responsible for several killings [37]–Caril was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Fugate spent nearly 18 years in the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women in York. A model prisoner, she was paroled in 1976. She moved to Michigan, refusing most interviews and living as quietly as possible. Meanwhile, Sheriff Romer continued to insist on her guilt: “She told me they made up a story to make her look good so she could get off. They tied up her hands and she worked them around so she got rope burns on her wrist. That way, they could say she was a prisoner.” [38] No contemporaneous accounts mention Fugate being restrained or having rope burns.

More than half a century later, some of the scars Fugate and Starkweather inflicted on the country remain. Many people will never forget the infamous crime spree that shattered the sense of security enjoyed by residents of these normally quiet, peaceful, largely rural communities. For them, the Starkweather murders signaled the end of the quiescent ‘50s while foreshadowing the turbulent ‘60s.

In response to a 2012 Casper Star-Tribune article on Starkweather and Fugate, one online commenter posted Fugate’s full name, address, phone number and recent marriage information—perhaps as a threat to her, or at least to remind her she could not expect to remain anonymous. As a screen name, the poster had taken the name of the Bennet, Neb. victim whose body had been left in a storm cellar: “Robert Jensen.” [39]

Fugate, now Carol Ann Clair, continues as of February 2020 to maintain she never participated willingly in the crimes. In 1996, the Nebraska Board of Pardons denied her application for a full pardon. A second request is due to come before the board February 18.

Resources

Books

- Beaver, Ninette. Caril. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1974.

- McArthur, Jeff. Pro Bono: The 18 Year Defense of Caril Ann Fugate. Burbank, Calif.: Bandwagon Books, 2012.

- Newton, Michael. Waste Land: The Savage Odyssey of Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate. New York: Pocket Books, 1998.

- O’Donnell, Jeff. Starkweather: A Story of Mass Murder on the Great Plains. Lincoln, Neb.: J&L Lee Publishing, 1993.

- Papa, Paul W. “It Happened in Wyoming.” Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press, 2013, 119.

Newspaper Articles:

- (An article on the apprehension of Starkweather and Fugate can be found in nearly every newspaper on either Jan. 30 or Jan. 31, 1958, or both.)

- “Authorities Say Nebraska Youth Killed 10 People,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan 1958, 5.

- “Charlie Wins a Pack of Cigarettes: Death Verdict Met Without Emotion,” Beatrice (Neb.) Daily Sun, 25 May 1958, 1.

- “Family Calls Starkweather Mad at World,” St. Petersburg Times, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

- “Fugate Parole Revives Memories of 1958 Manhunt,” Casper Star-Tribune, 9 May 1976.

- “Immortalized in Springsteen’s ‘Nebraska,’ the former girlfriend of notorious killer Charles Starkweather asks for pardon.” Washington Post, Jan. 30, 2020, accessed Feb. 11, 2020 at https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/01/30/starkweather-girlfriend-pardon/.

- “Investigator’s File Lends Fresh Look at Charles Starkweather Murder Spree,” Casper Star-Tribune, 8 Oct. 2012.

- “Nebraska Gets Killer and Girl,” (Long Beach, Calif.) Independent, 31 Jan. 1958, A5.

- “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

- “No Execution for Killer in Wyoming,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

- “Officer’s Assertion Contradicts Caril,” Beatrice (Neb.) Daily Sun, 31 Oct. 1958, 1.

- “Sister Says Caril Told Her to Leave Bartletts,” Lincoln Evening Journal, 14 Nov. 1958, 1-2.

- “Starkweather Now Admits 11 Slayings,” Casper Star-Tribune, 31 Jan. 1958, 1.

- “Starkweather Says Killings Self Defense,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

- “Tension Relieved in Town of Bennet,” Beatrice Daily Sun, 25 May 1958, 2.

Popular Media (Music, based loosely or completely on Starkweather-Fugate):

- Bruce Springsteen. Nebraska, 1982.

- Church of Misery, Badlands, 2009.

- Del Shannon, Keep Searchin’ (We’ll Follow the Sun), 1965.

- Icky Blossoms. Stark Weather, 2012.

- J Church. Hate So Real, 1994.

Popular Media (Film, based loosely or completely on Starkweather-Fugate):

- Badlands (1973).

- Murder in the Heartland (1993).

- Natural Born Killers (1994).

- The Sadist (1963).

- Starkweather (2004).

- Stark Raving Mad (1983).

Field Trips

Exit 151 on Interstate 25, 10 miles west of Douglas, Wyo., leads to the road to Ayres Natural Bridge, and is near the turnoff from the old U.S. Rte. 20-26 where Merle Collison was murdered and the police first caught up with Starkweather and Fugate. Starkweather fled east from there, through Douglas, and was captured about ten miles east of town on the old highway.

Illustrations

All the photos are by Chuck Morrison and Carl Ketchum of the Casper Tribune-Herald, from the Chuck Morrison Collection, Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks. The two Nebraska lawmen in the photo of Starkweather leaving jail are Sheriff Merle Kanopp of Lancaster County, Neb., and Captain Harold Smith of the Nebraska State Patrol.

[1] See photographs, page 2, Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958.

[2] Reports vary from 5-15 miles east of Douglas as to exactly where he was apprehended.

[3] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[4] “Family Calls Starkweather Mad at World,” St. Petersburg Times, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[5] “Starkweather Says Killings Self Defense,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[6] “Family Calls Starkweather Mad at World,” St. Petersburg Times, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[7] “Starkweather Now Admits 11 Slayings,” Casper Star-Tribune, 31 Jan. 1958, 1.

[8] “Authorities Say Nebraska Youth Killed 10 People,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 5.

[9] “Starkweather Says Killings Self Defense,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[10] “Starkweather Now Admits 11 Slayings,” Casper Star-Tribune, 31 Jan. 1958, 1.

[11] McArthur, Jeff. Pro Bono: The 18 Year Defense of Caril Ann Fugate, 32-33.

[12] “Authorities Say…” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 5, says all three were shot. Pro Bono (36) says Fencil was stabbed to death and that (18) Mrs. Ward was found with “a knife sticking out of her back.”

[13] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[14] “Authorities Say…” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 5, says that Collison’s autopsy documented nine bullet wounds from a .22-caliber rifle. “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2, says Collison was shot twice in the head, once in the neck, once in the shoulder and twice in the leg. It is possible that some of the wounds documented in the autopsy are exit wounds.

[15] Contradictions exist about Sprinkle’s age. “Authorities Say…” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 5, says he was 40 years old while “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2, says he was 29.

[16] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[17] “Authorities Say…” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 5. Upon examination, the gun was found to be empty.

[18] “Authorities Say…” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan 1958, 5, spells this Ainsley but Ainslie appears to be correct. Ironically, Ainslie was a Nebraska native.

[19] Papa, Paul W. “It Happened in Wyoming.” 119.

[20] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[21] “Starkweather Says Killings Self Defense,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[22] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[23] “No Execution for Killer in Wyoming,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[24] “Starkweather Now Admits 11 Slayings,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 31 Jan. 1958, 1.

[25] For technical reasons, Starkweather was only tried for the killing of Robert Jensen.

[26] “Charlie Wins a Pack of Cigarettes: Death Verdict Met Without Emotion,” Beatrice (Neb.) Daily Sun, 25 May 1958, 1.

[27] “Tension Relieved in Town of Bennet,” Beatrice Daily Sun, 25 May 1958, 2.

[28] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[29] “Sister Says Caril Told Her to Leave Bartletts,’” Lincoln Evening Journal, 14 Nov. 1958, 1-2.

[30] “No Charges Placed Against Girl,” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 2.

[31] Pro Bono, 30. Fugate has told multiple stories about how she learned her family was dead. She has said she learned it from Wyoming officials, from her sister and from Sheriff Karnopp’s wife.

[32] “Starkweather Says Killings ‘Self Defense,’” Casper Tribune-Herald, 30 Jan. 1958, 1.

[33] Caril also was only tried for the murder of Robert Jensen.

[34] “Officer’s Assertion Contradicts Caril,” Beatrice (Neb.) Daily Sun, 31 Oct. 1958, 1. Pro Bono, 103. The bodies of Marion and Velda Bartlett and their 2-year-old daughter were found stuffed in an outhouse on the family property on Monday, Jan. 27. Mr. and Mrs. Bartlett had been shot; young Betty Jean died of a fractured skull.

[35] Pro Bono, 108. Caril claimed she had a note seeking help from authorities in her pocket but the note was never produced.

[36] Romer’s account of Caril’s confession the day she surrendered did appear in one contemporaneous account. “Nebraska Gets Killer and Girl,” (Long Beach, Calif.) Independent, 31 Jan. 1958, A5.

[37] “Fugate Parole Revives Memories of 1958 Manhunt,” Casper Star-Tribune, 9 May 1976.

[38] “Fugate Parole Revives Memories of 1958 Manhunt,” Casper Star-Tribune, 9 May 1976.

[39] “Investigator’s File Lends Fresh Look at Charles Starkweather Murder Spree,” Casper Star-Tribune, 8 Oct. 2012.