- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Wyoming North and South Railroad, 1923-1935

The Wyoming North and South Railroad, 1923-1935

Abandoned railroads evoke nostalgia. Conceived in optimism, initiated with fanfare and laid out in orderly increments, these railroads pass through stages hauntingly similar to human development: growth, vigor, decline and demise. In the end, most railroads are forgotten.

One such enterprise, the Wyoming North and South Railroad, emerged onto the plains of Natrona County in 1923 as a 40-mile standard-gauge link of what was hoped to be a grand chain connecting trunk lines in Canada, Montana, Wyoming and Colorado. Due to the accelerated pace of the 20th century, the Wyoming North and South Railroad evolved from birth to abandonment in just 12 years. The following account is written in the nostalgic spirit that vanished railroads, like old friends, should be remembered.

Aspirations

Though promotion of large western railroad networks peaked during the late 1800s, there was enough momentum left to stimulate ambitious projects after the turn of the century. In 1902, David Moffat organized the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway Company to push westward from Denver across the continental divide toward the coast. The line progressed no farther than Craig in northwest Colorado (1913), later assuming the less expansive title of the Denver and Salt Lake Railroad Company, to be eventually absorbed by the Denver & Rio Grand Western and finally the Union Pacific.

For nearly a quarter century, until completion of the Moffat Tunnel in 1927, trains labored up and over 11,600-foot Rollins Pass, braving the most adverse conditions of snow, wind and cold ever encountered by western standard-gauge railroaders. The “Moffat Road,” as the line between Denver and Craig came to be known, was to play a role in the planning of an equally ambitious railroad, the North and South Railway Company, of which the Wyoming North and South Railroad became an integral part.

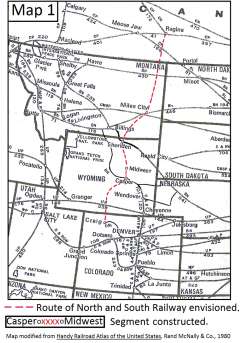

In 1922, former Oklahoma Gov. Charles N. Haskell, an oil promoter with interests in the Salt Creek Field north of Casper, Wyo., conceived the idea of a 566-mile rail line linking the Moffat Road at Craig, Colo., with the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad at Miles City, Mont. Haskell’s projected south-north route would also funnel traffic to and from the Union Pacific in southern Wyoming, as well as the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy (now Burlington Northern Santa Fe) railroads in central Wyoming. Haskell envisioned that his grand trunk line might someday be extended as far north as Regina, Sask. to connect with the Canadian Pacific Railroad! (See Map 1).

Organization and Incorporation

To speed construction of the first phase of the 335-mile north-south line between Casper and Miles City, the promoters decided to form two carriers under separate state charters, later to be merged into one company under the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission. On Dec. 31, 1922, the Middle States Oil Corporation of New York City incorporated the Montana Railway Company to construct and operate a railroad from Miles City to the Wyoming border, 138 miles to the south.

On Jan. 25, 1923, Middle States organized the Wyoming North and South Railroad to build 197 miles of line northward from Casper through Buffalo and Sheridan, Wyo. to the Montana border. Charter members of the Wyoming company were former Oklahoma Gov. C.N. Haskell, C.S. Lake, Peter Rohrbach Jr., C.A. Eastman and R.S. Healy, all residing in New York City. Incorporation papers noted that each of the five subscribed to 100 shares of capital stock at $100 per share for a total of $50,000, and that they expected to raise $7 million by selling 70,000 shares at $100 each.

The Wyoming secretary of state certified the Wyoming North and South Railroad Company to be a Wyoming corporation on March 21, 1923. Listed as officers in the Annual Report to the Wyoming Public Service Commission were: C.J. Haskell (son of Charles N. Haskell), president; Peter Rohrbach Jr., secretary; F.A. Winkler, auditor; W.M. Cannon, attorney; J.J. Foley, general manager; W.K. Sheridan, general superintendent; and D.C. Fenstermaker, chief engineer.

Construction

In January 1923, while promoters were busy incorporating the Wyoming portion of the railroad, C.S. Lake made a reconnaissance trip along the proposed route between Casper and Miles City. Engineers surveyed the line in February and March. Grading crews moved first dirt at Miles City on April 2.

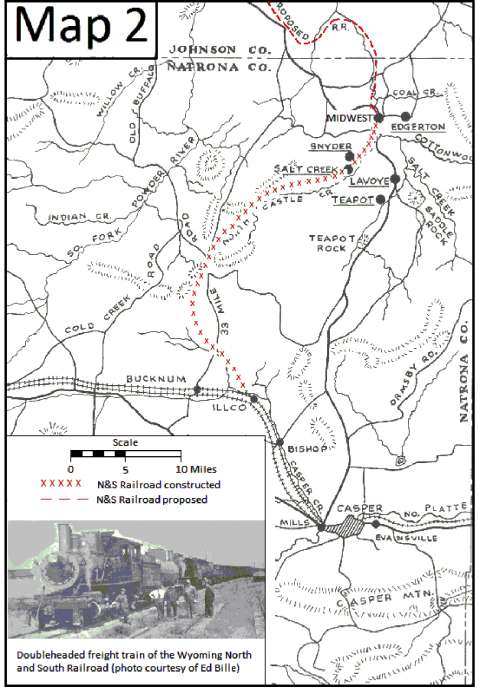

In late May, grading commenced at Illco (See Map 2), a small town located 15 miles west of Casper on the main lines of the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy railroads. Because the Wyoming North and South Railroad shunned publicity, few Casper residents realized that a rail connection was being built to the oil fields north of town.

Maney Brothers, a construction firm based in Wichita Falls, Texas, employed a force of 300 men (mostly black southerners) and 200 mule teams. Employees and families lived in tent cities which moved northward as grading progressed. Their work songs drifted across the prairie, a strange sound to the ranchers in this remote part of Natrona County. Three locomotives borrowed from the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific shuttled materials to the track-laying crews. A few reports on construction progress appeared in newspaper ads placed by the Wyoming-Montana Investment Company, which promoted sale of lots in the booming oil town of Salt Creek, soon to be the site of freight and terminal yards.

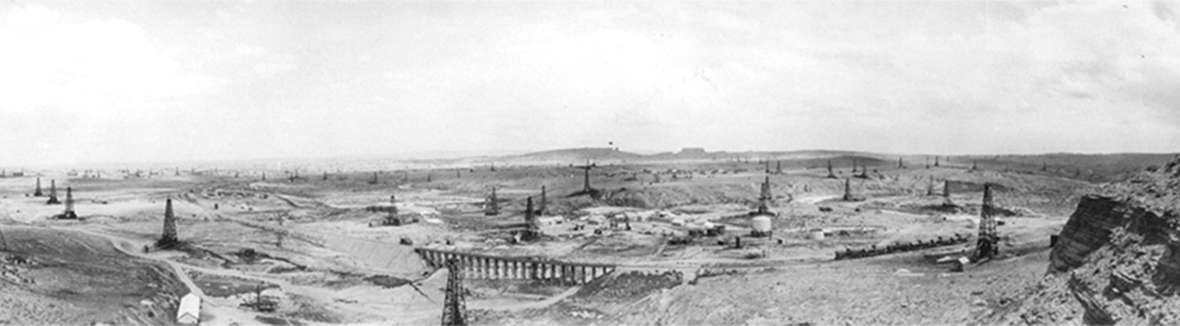

By mid-September 1923, tracks reached Salt Creek, 36 miles north of Illco. Discovered in 1906, Salt Creek Oil Field achieved its peak production of 132,000 barrels of oil per day, coincidentally, in the same month the railroad arrived. The field was served by the towns of Midwest and Edgerton, as well as by the now vanished communities of Salt Creek, Snyder, Lavoye and Teapot. In December, track laying progressed to Midwest, bringing mainline mileage to 41. Addition of yard and siding track increased the total to 45 miles.

Newspaper accounts heralded the “excellent condition” of the roadbed, citing 85-pound rail (per yard), maximum curves of 5 degrees radius, and maximum grade of 1 percent. Cross ties, numbering 3,040 per mile, were 8-foot lengths of untreated Oregon fir. Unmentioned by the press was the fact that the amount of crushed stone—so-called ballast—placed under the ties was insufficient to support them in areas of clay-rich soil, an engineering oversight that was to play havoc with future operations.

First Train

No ceremonies heralded inauguration of train service between Casper and Salt Creek on Sept. 25, 1923. Equipment on the first run consisted of a borrowed Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific team engine, a boxcar, one passenger coach and the private car of A.J. Worthman, superintendent of the local division of the Chicago & North Western Railroad. Departing from Casper at 7 a.m., the train arrived at Illco at 8 o’clock and Salt Creek at 9:50.

In an open letter to the president of the Casper Chamber of Commerce, published in the Casper Daily Tribune, C.S. Lake noted construction had taken just four months, attributing this feat to the “vision, courage and sincerity of purpose of Charles N. Haskell.” In later years, skeptics were to cite the haste with which the line was built and lack of sound construction as evidence that Haskell never intended to push the railroad farther north than Midwest.

1923-1924: A Fast Start

Initially, the Wyoming North and South Railroad, commonly referred to as the “North & South,” made use of terminal facilities of the Chicago & North Western. Regular westbound C&NW trains pulled passenger cars from Casper to Illco for transfer to the North & South line. Plans to extend North & South tracks into Casper never materialized. The fledgling railroad located its business offices in the Consolidated Royalties Building—the Conroy Building on Center Street —of downtown Casper.

Northbound mixed trains (freight and passenger) left Illco at 8 a.m. after connecting with early morning trains from Casper. The return train departed Salt Creek at 1 p.m. As the southern terminus of the North & South, Illco enjoyed the distinction of being the only town in Wyoming serviced by three railroads (Chicago & North Western tracks were paralleled at the time by Chicago, Burlington & Quincy tracks).

In addition to three railroad agency offices, Illco featured a post office, bar, large warehouse and laborers’ shacks. North & South business boomed at the beginning. Three small steam engines furnished motive power. Two ran in tandem (a practice called “double heading”), pulling two trains a day between Illco and Salt Creek, while the third handled switching duties.

In 1923, Nick Hahn joined the North & South as master mechanic and engineer. His daughter, Madeline Hahn Brott of Casper, recalled to the author years later that some 2 a.m. departures from Salt Creek. The Hahns lived in a section house in Salt Creek, shared by another engineer, R.S. Bell. In 1924, Nick’s son, Carl Hahn, joined the railroad, making the North & South a family enterprise.

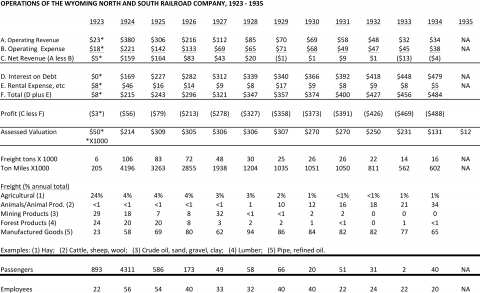

During the three months of operation in late 1923, the North & South carried 6,000 tons of freight and 893 passengers (Table 1). Employees numbered 22. The railroad took in modest operating revenue totaling $23,000, offset by $18,000 operating expenses. Equipment rentals of $8,000, when added to expenses, accounted for a loss of $3,000 (See table).

Although tracks terminated at the town of Midwest by the end of 1923, grading for extension of the railroad progressed in the Buffalo and Sheridan areas. A report to the Wyoming Public Service Commission noted that by the end of 1924, a total of $2,865,556 had been invested in construction of the Wyoming North and South Railroad.

The need for stronger motive power became apparent as more freight flowed onto the North & South. Nick Hahn was dispatched to Atlanta, Ga., to fetch a larger engine. Finding the machine unsatisfactory, he spent 55 days in that southern city supervising cleaning and repair of the equipment to meet his standards. Later, a second engine was obtained in Atlanta and a third brought from Shreveport, La. All were oil-burning steam locomotives of the 2-8-0 variety (two pilot wheels, eight drivers, no trailing wheels under the cab), numbered 101, 102 and 202.

In terms of freight volume, 1924 represented the peak of North & South operations. The three locomotives worked overtime to haul 106,000 tons, aggregating 4,196,000 ton-miles (tons multiplied by miles transported). Principal commodities were crude oil, sand and gravel, lumber, oil field equipment and refined petroleum products (Table 1).

Most of the heavy equipment that went into the Salt Creek electric plant, placed in operation in January 1925, traveled by rail. A total of 4,311 passengers rode the rails in 1924. The employee roster jumped to 56. Gross operating revenue increased to $380,000 and expenses amounted to $221,000, yielding a net of $159,000. For the first time, an ominous entry called “interest on debt” appeared on the ledger. Interest of $169,000 exceeded net revenue and, when combined with other impairments, yielded a loss of $56,000.

On May 8, 1924, as envisioned by the promoters, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) granted a corporation called the North and South Railway Company the right to combine the similarly named Wyoming North and South Railroad and Montana Railway Company into a single interstate carrier. The merger was undertaken without exchange of money, with the understanding that investment in the constituent companies would be liquidated as soon as the North and South Railway Company made arrangements to obtain money under a method of financing approved by the ICC.

The new North and South Railway Company turned out to be ill-fated. On July 31, 1924, the district court in Johnson County, Wyoming, judged that the North and South Railway Company and Wyoming North and South Railroad were identical and that both were insolvent. The court appointed Charles S. Hill and D.C. Fenstermaker as receivers.

A month later, the Montana Railway Company was also handed over to receivers. These legal actions were undertaken to protect creditors on account of large unpaid construction bills. Among companies establishing liens against the North & South were the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad, the Cloud Peak Timber Company, and Roberts Brothers, Peterson, Shirley & Gunther. To make matters worse, the latter company was eventually sued by a subcontractor for grading work done in Montana.

Receivers expressed hope that financial affairs could be straightened out to the end that responsible parties would take over the North and South Railway and resume work on the original project of linking Casper to Miles City. Such was not to be. Construction never resumed. Prior to receivership, grading had been completed over one-third of the Montana portion of the projected railroad line and one-third of the Wyoming part. From 1924 to abandonment in 1935, the North and South Railway (one and the same with the Wyoming North and South Railroad) operated as a ward of the court.

1925-1926: Solid Performance

Though freight volume decreased 22 percent to 83,000 tons in 1925, reduction in operating expenses enabled the North & South to realize net revenue of $164,000, which proved to be the fiscal high point of the line’s brief career. As might be expected for a railroad terminating in an oil field, a large proportion of the tonnage (43 percent, or 36,077 tons) consisted of pipe for oil wells.

Interestingly, the railroad carried 7,497 tons of refined oil to Salt Creek and Midwest, bringing a 20th century twist to the expression “carrying coal to Newcastle.” The reason for this reversal was that the refineries were in Casper, and the busy Salt Creek communities consumed large quantities of gasoline and other petroleum products. Crude oil, on the other hand, never contributed more than a small percentage of freight, owing to the oil pipelines that already ran from Salt Creek to Casper.

For the first two years of the railroad’s existence, locomotives burned crude oil taken directly from an oil company stand pipe at Salt Creek. By the end of 1925, however, engines were converted to burn processed crude purchased by the tank carload from Casper.

Madeline Brott recalled that her father, Nick Hahn, frequently complained about the poor quality of oil brought from Casper. One day, Superintendent Sherman D. Canfield (a former secretary of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show), who had replaced W.K. Sheridan strolled by while Carl Hahn was behind the section house rendering a badger to extract the animal’s fat. Sniffing the fetid vapors, Canfield explained “this oil is bad!” and ordered a new shipment of boiler fuel the next day.

A bad omen for the railroad was loss of a mail contract on Sept. 1, 1925. The government awarded the mail to a bus line, which made three daily trips from Midwest to Casper.

On Sept. 8, 1925, Charles Hill resigned as receiver, leaving D.C. Fenstermaker the sole proprietor of that position.

In early 1926, a series of stories in the “Salt Creek Gusher” rekindled hopes for extension of the North & South to Miles City. The newspaper offered a map of the proposed route provided by Hugh Lee Kirby, president of the “Wyoming Montana Railroad Company.” Wyoming Sen. John B. Kendrick reportedly urged financial interests to complete arrangements for backing the project. Completion cost was estimated at $17 million.

Net revenue for 1926 declined to $83,000, about half the previous year’s total. This drop, combined with inexorably rising debt, produced a loss of $213,000. Nevertheless, business was still relatively healthy, as the railroad hauled 72,000 tons.

On July 8, 1926, a flood triggered by the second cloudburst in four days hurled a 500-barrel tank into a trestle that spanned a creek between the towns of Salt Creek and Midwest. According to Madeline Brott, the trestle was suspect even after normal heavy rains. At times, engineer Nick Hahn was so concerned that he would not let his son, Carl, ride the locomotive across the structure.

Of course, there was no doubt about the condition of the trestle after July 8; the rails hung by a thread. Repairs were made by jacks–165 of them–until more permanent restoration could be made. Driving locomotives over this jury-rigged structure was a hair-raising job. Rail service between Salt Creek and Midwest did not resume until July 30.

In 1926, the North & South listed total trackage of 45.4 miles, which included 41 miles of main line plus sidings at Salt Creek and Midwest, together with long-forgotten turnouts at Williams, Carter, Kasoning, Mutual, Ohio, Codona and Lakota. A passing track was located at Owens, and a water tank marked the midway point.

The equipment roster of the North & South was never very extensive. In addition to the three locomotives, the railroad owned two combination freight and passenger cars, two flat cars, two tank cars and two cabooses. Freight transferred in rolling stock from other carriers generated almost all the revenue. Madeline Brott remembered well the shiny oil-burning steam engines that seemed to pass perilously close as she made the daily trip from the section house to the freight yard to hand lunch up to her father.

D.C. Fenstermaker resigned as receiver in 1926 to be replaced by R.E. McNally of Sheridan, who was to hold this position for the duration of the railroad’s existence.

1927-1934: Struggle to Survive

Net revenue plunged to $43,000 in 1927, a year which saw freight volume fall off 33 percent to 48,000 tons. Only 49 passengers travelled by rail, as opposed to 4,311 three years before. Clearly, improving auto roads were siphoning off freight and passenger traffic. Ironically, a substantial share of freight in 1927 consisted of road building materials. Volume of sand, gravel and clay, considered “mining product,” jumped to 12,390 tons—27 percent of all freight—as compared to 4,262 tons the previous year.

Shortcuts taken in construction, particularly omission of ballast, took their toll of railroad operations during the middle years. Flash floods frequently cut roadbed and bridges. Nick Hahn recalled daily derailments, one of which dumped 10 cars of gravel on Rock Cut curve near Shepperson Ranch. A C. & N.W. wrecker came to the rescue. Once, the water tender, which rode just behind the engine, suddenly jumped the track and streaked across the prairie.

Because of the unpredictable condition of the roadbed, engineers tried to hold speed below 20 mph, not always possible on the long downgrades on the flank of Twenty Mile Hill. Carl Hahn remembered that the pitching and rolling of flat cars often tossed pipe over the embankments. Coming south toward Illco the day after a night run to Salt Creek, the crew was astounded to see pipe sticking out of the soft ground like telephone poles.

Harsh winters contributed to operational problems. Madeline Brott recalled that during the winter of 1930-1931, 30 men toiled 10 days to clear snow that blocked the railroad at Petterson’s Cut. On the lighter side of operations, the North & South took time out from a busy schedule to shuttle revelers among Salt Creek, Lavoye and Midwest during Saturday night dances.

The mineral-rich water supplied to the Salt Creek boom towns played havoc with locomotive boilers. Madeline filled out boiler washout reports as her father strived to keep the boiler tubes free of scale. Notwithstanding his efforts, the boilers sprang leaks so often that a special tank car was hooked behind the tender on each trip to furnish extra water if needed.

Freight volume fell further still in 1928 to 30,000 tons. Refined petroleum products (treated as “manufactured goods”) contributed 17,000 tons, representing 57 percent of all freight. The employee roster numbered 32, compared to the 1924 high of 56.

With the beginning of the Depression in 1929, the North & South for the first time failed to show a net gain from operations. Though the shortfall was only $1,000, this deficit was the harbinger of future difficulties. On Nov. 27, the District Court of Johnson County authorized sale of four receiver certificates, each paying 7 percent interest on face value of $25,000. Not surprisingly, only one was purchased.

A bright note in 1929 was the upswing in livestock business. Sheep and cattle added 2,600 tons to the freight roster, together with 327 tons of wool. Livestock and animal products comprised 10 percent of total haulage, a figure that grew to 34 percent by the last year of operation. Sheep and cattle from the Big Horns, Gillette, Kaycee and Buffalo converged on Salt Creek for twice weekly hauls to Illco and points beyond during the fall shipping season. The railroad moved 30 to 35 carloads of animals each week.

Operating revenues continued to decrease from 1930 through 1933, a year that recorded revenues of $32,000 against expenses of $45,000. Only two passengers bought tickets in all of 1933! On many occasions, employees found themselves empty-handed on paydays. Engineers and mechanics had to improvise to find badly needed spare parts. The office of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad furnished many materials.

In the annual statement to the Wyoming secretary of state for 1933, auditor and treasurer C.W. Kimball of Salt Creek listed book value of equipment and real property as $119,436. For the same year, the State Board of Equalization levied an assessment of $231,000, no doubt following the practice of valuing railroad property based on miles of main line.

In 1934, the final full year of operation, the North & South carried just 16,000 tons of freight. By then, annual interest on debt had soared to nearly a half million dollars, truly a staggering sum for an enterprise which recorded a revenue deficit.

1935: End of the Line

Soon after the first of the year, R.E. McNally, who had served as receiver for more than eight years, secured a court order to curtail operations, after which he filed a petition for abandonment. Without fanfare, the last train steamed southward into Illco on March 8, quietly ending an era that had quietly begun 12 years earlier. Ironically, five days before the last run, the Casper Tribune-Herald proclaimed in a headline “North and South Railroad Project Still Live Prospect in State.”

In the fall of 1935, rails were torn up and shipped to China. The engines were cut up at Illco. Boilers were installed in a Riverton refinery. No doubt the assessed valuation of $12,000 reflected scrap value.

Perspective

On a local scale, the Wyoming North and South Railroad was built too late to effectively bridge the gap between slow, expensive horse-drawn freighters and efficient high-volume motorized transport by truck, bus and car. As a regional north-south trunk line, however, tie-in with the Union Pacific, Burlington and, possibly, Canadian Pacific Railroads was an idea of considerable merit.

In answer to suggestions that the North and South Railway originated as a scheme to fleece gullible investors, records show that over a hundred miles of grading and 45 miles of track laying were completed with funds advanced solely by the promoters, before capital stock or other securities went public. Receivership forestalled issuance of stock during the remainder of the railroad’s existence. Simply stated, the North & South Railroad of Wyoming was built as part of a flawed vision, overtaken by 20th century transportation realities.

Crumbling embankments and cuts still mark the abandoned course of the Wyoming North and South Railroad, as it arcs northwestward and then northeastward across northern Natrona County’s 33 Mile Road toward Midwest. In places, mounds of earth that once bore rail and locomotive now impound water for livestock that roam a landscape where whistles wail no more.

Acknowledgements

I wrote “The Wyoming North and South Railroad, 1923-1935” as a term paper for History of Wyoming, a Casper College course taught by acclaimed historian William F. Bragg Jr., in the fall of 1982. Bill’s enthusiasm kindled my fascination with Wyoming history. The only changes from the original manuscript are notations of the current ownership of railroads that changed hands since 1982.

Although the Wyoming North and South Railroad contributed significantly to the growth and vitality of the Salt Creek area during the mid-1920s, initially forming a reliable transportation link when roads were still inadequate, few written accounts of the line exist. As a result, I relied heavily on unpublished records, most of which came to light through efforts of Jim Donahue, Archives Research Supervisor in what then was called the Wyoming State Archives, Museums & Historical Department. Division Director Bill Barton pointed the way, and Ida Wozny lent assistance.

Mary Lynn Corbett of the Natrona County Public Library provided several information leads and secured copies of two elusive newspaper articles. Ed Bille, author of Early Days at Salt Creek and Teapot Dome, a colorful account that stimulated my interest in the North and South Railroad, kindly gave permission to reproduce a map and photo.

Statistics and legal documents provide little flavor. For this reason, I am especially grateful for the shared recollections of Madeline Hahn Brott, whose father Nick Hahn and brother Carl served the Wyoming North and South Railroad faithfully and well during its brief existence.

Resources

Primary sources

Documents

- Articles of Incorporation of Wyoming North and South Railroad Company (State of Wyoming, Office of the Secretary)

- Certificates of Agent and Place of Business, Wyoming North and South Railroad Company

- Annual Statement to Secretary of State, Wyoming North and South Railroad Company (Microfilm)

- Minutes of Wyoming State Board of Equalization

- August 11, 1914 to March 31, 1924

- April 1, 1924 to December 31, 1941 (Microfilm)

- Public Service Commission

- Annual Report of the North & South Railway Company, aka Wyoming North and South

- Railroad Company (Microfilm)

- Note: All of the above documents are available from the Wyoming State Archives.

Periodicals

- Casper Daily Tribune

- “Salt Creek rail service launched.” September 25, 1923

- “Bridges washed out,” July 9, 1926. P.1.

- Casper Tribune-Herald

- “North and South Railroad Still Live Project in State,” March 3, 1935

- “Dream Railroad,” April 9, 1950

- Casper Star Tribune

- “North and South Railroad,” Annual Edition, February 13, 1955

- Midwest Review

- “Building Railroad through Salt Creek,” Vol. IV No. 5, June 1923

- “First Railway Train into Salt Creek,” Vol. IV No. 9, October 1923

- “Railroad Rails into Home Camp,” Vol. IV No. 11, December 1923

- “Flood Causes Troubles,” Vol. VII No. 8, August 1926

- Salt Creek Gusher

- “Railroad Completion Looking Good,” Jan. 15, 1926

- “Salt Creek Chamber of Commerce Receives Map Showing RR Extension,” Jan. 222, 1926

- “Completion of Wyoming-Montana Line Will Be Big Boon to the Whole State,” Jan. 26, 1926.

- “North and South to Begin Work Soon,” Feb. 19, 1926.

- “Effort Made to Speed Work on North & South,” March 19, 1926

- “RR Officials Visit Salt Creek,” April 23, 1926

- “Contractors are Sued by Subcontractors,” Sept. 24, 1926.

Secondary sources

- Bille, Ed, Arlene Larson, and Bill Dickerson. Early days at Salt Creek and Teapot Dome. Casper, Wyo.: Mountain States Lithographing, 1978.

- Bollinger, E.T., and Bauer, F., 1962, The Moffat Road; Chicago, The Swallow Press, Inc. 359 p.

- Roberts, H.D. Salt Creek, Wyoming; The Story of a Great Oil Field. Denver: Midwest Oil Corporation, 1956.

Illustrations

- The photo of Charles Haskell is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The two maps are from the author’s collections and the fact box was prepared by him. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the two locomotives is from the Garrett collection and the photo of the washed-out trestle is from the Wyoming Highway Department collection, both at the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The panorama of the Salt Creek Field, 1924, showing the trestle and a line of tank cars on a North and South Railroad siding, is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.