- Home

- Encyclopedia

- A Kid In Hell On Wheels: Laramie As The Railroa...

A Kid in Hell on Wheels: Laramie as the Railroad Arrived

Billy Owen never saw a railroad until he was eight years old. His mother had told him about railroads. But in his mind as he traveled east by wagon train across Wyoming in the spring of 1868, he had imagined railroad wheels that looked something like wagon wheels. They rolled in grooves. Each groove was made by two rails. That meant it took four rails, as he imagined it, to make a track.

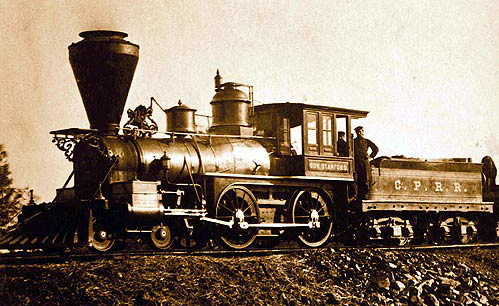

Sixty-two years later, when he sat down to write the story of his life, Billy (right, as a teenager) still recalled his amazement when their wagon rolled across the railroad tracks and into the brand-new town of Laramie. Somehow, the cars could run on just two rails! His mother explained to him that the steel railroad wheels had rims to keep the engine and cars on the tracks. Still, he wasn’t satisfied until he saw a train for himself — the engine with the big wheels, the cowcatcher on the front, the smokestack coughing sparks and wood smoke, the tender behind it full of firewood, the windowed cars the people rode in, and the box cars the things rode in all following obediently along. As the train pulled to a stop, the steam hissed, the brass bell clanged, and the big whistle let out a loud, shrill scream.

When they arrived in Laramie, the Owens ended a difficult family journey that had begun in England long before. Billy’s parents had lived near Bristol, on the west coast of England. They were married in 1852, and Billy’s older sister Eva was born a year later. By this time, many Mormon missionaries from the Salt Lake Valley of Utah were spreading the word of their new faith in England. The Mormons — members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — had first arrived in Utah in 1847. There they could practice their religion free from trouble, and the new church grew fast.

In England, Billy’s father, his mother’s brother, and his mother’s parents all joined the church. In 1854 Billy’s parents and his sister Eva, just six months old, made the long trip by steamboat to New Orleans, up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers by riverboat, and finally overland by wagon train all the way to Utah. Billy’s mother, however, had never joined the church. When they got to Utah, she discovered to her surprise that many Mormon men had more than one wife. This made her deeply angry, and though her husband and nearly all her neighbors in Pleasant Grove, Utah, were Mormons, she never would join. Billy’s second sister, Etta, was born in 1856. Billy’s mothers’ parents and his uncle Jim arrived in Utah in the late 1850s. Billy, the youngest, was born in 1859.

In spite of his wife’s feelings, Billy’s father remained a loyal Mormon and became an important man in the church. Finally, Billy's mother told her husband he must choose her or the church. He chose the church, and went back to England as a missionary. This made it very hard for the Owens. For three years, Billy’s mother and Eva moved to Boise, Idaho, where there were new gold mines. They ran a restaurant for the miners and had a little store. Billy and his sister Etta stayed in Utah with their grandparents, and went to a school run by the Episcopal Church — one of the few non-Mormon schools in the entire valley. Billy’s mother and Eva worked hard, saved money, and finally returned to Utah in 1866. But again, she decided Utah was not the place for the Owens. This time, however, she had enough money to take all her children with her. In May of 1868, she bought places for Eva, Etta, Billy, and herself on a wagon train headed east, toward Wyoming.

Billy and his family arrived in Laramie on June 14, 1868, after a trip of three weeks and 450 miles. The town was brand new, and the railroad had made it happen. The transcontinental railroad was building west across Wyoming. In early May, the tracks had reached Laramie. With them came thousands of workers, and hundreds of gamblers, prostitutes, and criminals skilled at separating the workers from their pay. Quite suddenly, Laramie was a town of 1,000 people, most of them living in tents. It had almost no government. Such towns were known as the End of Tracks or, more often, Hell on Wheels. A newspaper, the Frontier Index, kept its printing press and offices in a railroad car, as it had to move so often to the next End of Tracks.

Two companies built the transcontinental railroad. Mostly Chinese workers built the Central Pacific Railroad east from Sacramento, California. The Union Pacific (below) was built west from Omaha, Nebraska, mostly by Irish workers, along with many veterans of the Union and Confederate armies. Each company was racing to get as far as it could across the continent before it met the other. To encourage the companies to take on such a huge job, the federal government gave them enormous tracts of land on both sides of the track, and paid them a certain amount per mile once the tracks were built and approved. This meant that the more track they laid, the more government money the railroads could claim. It also meant the railroads were built sloppily—with wobbly bridges, ties not well anchored in the ground, and rails that moved around too much as the trains ran over them. Accidents happened often. But the men who owned the railroads figured those problems could be fixed up later. The main thing now was to build the railroad.

Near the end of 1866, the Union Pacific tracks reached North Platte, Nebraska. The next summer, Hell on Wheels was at Julesberg, in the northeast corner of Colorado—the same Julesberg that the Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota tribes had raided just two years earlier. Julesberg may have been the wildest of all the Hell on Wheels towns. One night, railroad construction boss Jack Casement and around 200 railroad workers felt they had to kill a number of gamblers. Things calmed down after that. By the end of 1867, the tracks had reached Cheyenne. In the spring, the tracks continued over the mountains to the west, and reached Laramie in early May, five weeks before the Owens did.

Billy’s mother rented some rooms in a hotel on what’s now First Street in Laramie, facing the tracks. Soon she opened a restaurant and store, just as she had in Idaho. Eva and Etta, by then 15 and 12 years old, helped their mother a great deal. (Owen-Nelson, 1938, p. 4) There were plenty of respectable people in town, Billy remembered 62 years later when he wrote an autobiography. There were also plenty of “bar room bums, thugs, garroters [that is, stranglers], holdups, thieves and murderers from railroad towns to the eastward, and the doings of this mob of criminals form a thrilling page in the history of Laramie.” (Owen autobiography typescript, p. 4) Thrilling, perhaps, when a person thinks back on it. But it must have been pretty terrifying to an eight-year-old boy.

Across the street from the Owens’ restaurant was a tent nearly half a football field long, taking up an entire city lot . It had a wooden floor, for dancing, and long bar down the right-hand side as a person entered. Gambling tables took up the rest of the space. A band played full time. There were 20 or 30 women whose job it was to dance with the railroad men, and then lead them to the bar afterwards so they would buy expensive drinks. Most of these women were also prostitutes. Gambling and dancing went on all night. All his life Billy would remember the Keno dealer yelling, “Keno is correct!” and the square dance caller yelling “Promenade to the bar!” after each dance.

One day that summer, Billy was watching through the window when suddenly a crowd of men and women rushed out of the tent into the street. A man ran from the crowd, chased by a second man, carrying a pistol. The first was in the middle of the street when the second shot him, and “dropped him in his tracks,” Billy remembered. The crowd carried the injured man to an upstairs room, where he died soon. Ten minutes later the street was clear of the people, and the music, dancing and gambling going again full blast.

A city government was formed briefly that spring, but it soon fell apart. There was no Wyoming yet. Cheyenne and Laramie were still part of Dakota Territory, with its capital at Yankton, 450 miles away.

By late summer, people were being robbed in broad daylight and the criminals were pretty much running the town. At the same time, the End of Tracks had moved to towns further west. Laramie’s “better element,” as Billy called it, was growing, and these people decided things had gotten bad enough. They organized a vigilance committee—a committee of vigilantes ready to take the law into their own hands. In late August they hanged a man Billy remembered only as “the Kid,” — but that only increased bad feelings in town and didn’t stop the crime.

In October, the vigilantes raided the homes of three men — Asa Moore, Con Wagner (or Wager, or Wagan) and Ed “Big Ned” Wilson, shot them full of bullets, and then hanged their bodies from the end of a log building downtown. The same night, they told a number of other toughs to leave town immediately or face the same treatment. Next morning, Billy and his pals got a long look at the bodies. They recognized Moore by his big red flannel neckerchief.

Later the same day, Billy and his friend Phil Bath were in the street when they saw a group of men come out of a saloon, one carrying a coil of rope. In the middle of the bunch was a man known to all as “Long Steve”—one of the men who’d been warned the night before. He hadn’t left town. They took him to a telegraph pole near the corner of what are now Grand Avenue and First Street, by the tracks, and hanged him from the cross arm of the pole. A big crowd had gathered. Phil and Billy watched from 20 feet away. His sister Eva watched from further back in the crowd.

That Billy would remember these events six decades later as “thrilling,” and not horrifying, as we might like to think they were to an eight-year-old, says something important about Billy and his times. He had a mostly ungoverned boyhood. He roamed the streets playing pranks with his friends. He roamed the creeks fishing and the prairies hunting with the same friends. They hunted with an antiquated black-powder musket out of which they would shoot gravel and nails when they ran out of bullets. Perhaps Billy’s mother and sisters were too busy running the business to pay him much attention. Or perhaps most boys’ families let them run wild, figuring they would learn important things as they did so. Billy certainly did.

As for Laramie, it got safer after the vigilance committee finished up its work, Billy remembered. Soon a real city government was established. Wyoming officially became a territory that summer of 1868, but no federal officials arrived to run it—no real law — until the following spring.

Meanwhile other towns along the tracks felt they had to use the same tactics. Three men were lynched in Dale City, a construction camp west of Cheyenne, in January 1868. In March, two more were lynched in Cheyenne itself. Then the four in Laramie, and in October, not long after the Laramie lynchings, five men were lynched in Bear River City, later called Evanston, in Wyoming’s southwest corner.

Billy grew up to be a small man, only five feet tall, which is perhaps why people called him “Billy” all his life. He made up for his size with fierce energy and ambition. He became Wyoming’s best-known surveyor. He loved the work, both the math and the walking. He was the first person to ride a bicycle through Yellowstone Park, in 1883, and he and a party of friends were the first people to climb the Grand Teton. Mount Owen, in the Tetons, is named for him. In 1894, he was elected state auditor, one of the five top elected officials in Wyoming. He lived most of his life in Laramie. After he retired he moved to California, but continued to spend his summers in Jackson Hole.

He and his wife, Emma, never had children. She weighed 250 pounds, and loved to bake him cakes. Billy’s great niece, Alice Downey Nelson, remembered him years later as a smart, fussy man with a short temper and a long, clear memory, who loved to tell stories.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Owen, William O. Unpublished autobiography, ca. 1930. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, William O. Owen collection, #94, Box 1. There is a handwritten version, labeled volume 1, but no second volume has ever been found. Page numbers refer to a typewritten version in the same collection.

- Owen, William O. to Barbara Nelson, May 9, 1938. William O. Owen Collection, Jackson Hole Historical Society, Jackson, Wyoming. This collection contains a lot of clippings and correspondence about the ascent of the Grand Teton. Barbara Nelson was Billy’s great niece. His letter to her details the Owen family’s emigration and difficult years in early Utah, items omitted from the autobiography.

- Nelson, Alice Downey. Unpublished memoir, “Mother is a Grand Old Name! An American Family Grows Up.” August 1950. Copy at Albany County Public Library. Chapter VIII, pp 86-103, is devoted to “Uncle Will” — Billy Owen. Besides the portrait of Billy’s personality is an account of his involvement in the discovery that the Ames Monument was not built on railroad land.

Secondary Sources

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Nothing Like it in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000. Ambrose very much admires the men who got the railroad built. Chapter 12, pp. 249-277 covers the building of the Union Pacific across Wyoming.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965. Chapter 3, pp. 33-66, covers the building of the UP, and places Laramie’s vigilante actions in the context of other towns’ handling of similar problems.

- Lyon, Peter. To Hell in a Day Coach: An Exasperated Look at American Railroads. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Company, 1968. A largely forgotten book that offers a more skeptical look at American railroad construction and especially finance. See Chapter 2, 29-48, for what was going on behind the scenes as the Central and Union Pacific railroads were built.

Online

- A great place to start browsing for information on the transcontinental railroad is the PBS website for a documentary produced for Public Television’s American Experience Series. See especially the description of Hell on Wheels. PBS also offers a series of lesson plans on the transcontinental railroad that relies heavily on primary sources.

- See the Union Pacific’s version of its own history and construction for timelines, historic photos, scenic photos, celebrity photos, maps, and more.

- A National Park Service website about the Golden Spike National Historic Site at Promontory Point, Utah, where the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroad tracks met in May, 1869, is full of links and information. See, for example, the clear diagram of how a steam locomotive works.

- As on so many subjects from Wyoming's past, Wyoming Tales and Trails is full of info on the transcontinental railroad and especially full of good photos, some of which I've used here. (See credits, below)

- And finally, see a great article about Billy Owen by the Bureau of Land Management's Sam Drucker, who relocated the survey corners Billy marked with dinosaur bones in the 1880s.

- All sites are full of additional links and resources.

Field Trips

- There are exhibits on the railroad at the Sweetwater County Museum in Green River; the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins, 307-328-2740; and in the “Drawn to this Land” exhibit at the Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne.

- See also the state tourism office’s “trainspotting” site.

Credits

- The photos of Billy Owen are negatives number 28580 and 4074 in the William O. Owen photo file at the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Copy and use restrictions apply.

- The images of the locomotive and the gamblers in front of the tent are from the of Union Pacific's excellent online collection of historical photos. Benton, Wyo., where the photo was taken, was briefly End of Tracks after Laramie was. Benton was near the North Platte River east of Rawlins and died quickly after the End of Tracks moved west. But the big tent in the photo is probably the same one Billy remembered. It, like the gamblers, moved west with Hell on Wheels.

- The woodcut, by Alfred R, Waud, shows UP construction in Nebraska in 1867. That image and the one of the three hanged men are from Wyoming Tales and Trails.