- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Grave of Mary Homsley

The Grave of Mary Homsley

Scholars estimate that the year 1852 saw the largest number of emigrants ever on the transcontinental trails. Late in 1850, Congress had passed the Donation Land Act, guaranteeing free land to pioneers who could make it to Oregon Territory. Soon, California Gold Rush travelers were joined by a surge of people bound for Oregon. It was a crowded year on the plains, with long columns of covered wagons heading west.

Not coincidentally, 1852 is also estimated to be the year of the greatest mortality on the trails, caused principally by the cholera epidemic then plaguing most of America. Wyoming has seven extant graves of that year’s casualties, but one of these victims, Mary Homsley, succumbed to a disease almost as deadly in nineteenth-century America—the measles.

Conflicting records say that Mary Elizabeth Oden was born either near Truxton, Lincoln County, Mo., in 1824 or near Lexington, Ky., where her parents lived before moving to Missouri. Her father and mother, Jacob and Sarah (Fine) Oden, did eventually settle with their family in Warren County, Mo., where on June 3, 1841, Mary married farmer and blacksmith Benjamin Franklin Homsley. He was a native of Tennessee and 11 years older than she—born in 1815. The young couple settled on a farm located in Warren County close to where Benjamin’s brother, Jeff, and his family lived.

In April 1852, accompanied by Mary’s parents and 10 brothers and sisters, some with families of their own, they took the trail to Oregon. There was family precedent for this move. Mary Homsley’s Aunt Delilah (Fine) Shrumb had emigrated to Oregon with her husband in 1846.

The Homsleys had three children at the time of their departure: Laura (sometimes spelled Leura or Lura), age 6, 2-year-old Sarah Ellen and a baby boy, whose name is now unknown. Left behind in Missouri were the graves of their two oldest, Georgina and Lycurges. The children had been poisoned by a household slave, murdered in revenge for perceived ill treatment by Benjamin Homsley. Family tradition has it that they were twins, but the 1850 census says Georgina was 9 in that year, Lycurges, 7.

Many wagon train companies were hit hard by cholera, and the Oden clan was no exception. Bryant Thornhill, husband of Mary’s sister Rebecca (Oden) Thornhill, is reported to have succumbed to cholera “soon after” Mary Homsley had died, as did Samuel Thornhill from the same cause. It is likely the two men were brothers. In a letter dated June 20 from Fort Laramie reporting their deaths, they are both said to have been from Warren County. Rebecca gave birth to a son in Oregon in February 1853, eight months after Bryant’s death. The baby was named Bryant Gray Thornhill Jr. after his deceased father.

Shortly before Bryan and Samuel Thornhill contracted cholera, Mary Homsley and her baby son came down with measles, a serious affliction in early America. An epidemic of it broke out in the wagon train, and most of the children and some adults came down with the disease.

For several days a feverish Mary and the baby rode on a featherbed in one of their two wagons driven by 14-year-old Bailey Homsley, Benjamin Homsley’s orphaned nephew. When they crossed the river near Fort Laramie, either the Laramie or the North Platte, the wagon overturned, and Mary and the baby were immersed in the frigid water. Both were rescued, but Mary’s condition took a turn for the worse and on June 10, while they camped a mile west of the fort near the North Platte, she died.

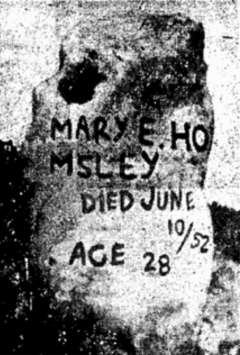

With no lumber available for a coffin, Mary was wrapped in a feather bed and, as Laura said decades later, “They were buried by the side of the road. When Father buried Mother he found a piece of sandstone. With his jackknife he scratched this inscription ‘Mary E. Homsley, died June 10, 1852, age 28.”

When she was interviewed for a newspaper story 80 years later, Laura believed that the infant boy had died at nearly the same time as his mother. Other accounts say the baby lived for another several weeks, passing away sometime in July when the company was in western Idaho. Benjamin buried the boy in an improvised coffin made from a tool chest.

With her last words, Mary asked that Benjamin keep their children together. It was common practice in those days for widowers to give up their young children to be raised by aunts or grandmothers, especially girls who needed a mother to train them on how best to bring up the next generation, or so it was thought. Several family members were candidates for that position, in particular Grandmother Sarah Oden, but Benjamin granted Mary’s last request, raised the two girls himself and never remarried.

“Father taught us to cook and sew and keep house,” Laura remembered many years later. When they arrived in Oregon, Benjamin took a Donation Land Act claim on Elliott Prairie in Clackamas County—in the Willamette Valley about 25 miles south of Portland—where he helped to build Rock Creek Church. He lies there, buried in the church cemetery. Benjamin Franklin Homsley died in 1908 a few days short of his 93rd birthday.

One of Mary’s younger brothers was reported lost somewhere on the trail and never heard from again, so the company lost at least five of its members on their way to Oregon in events not atypical for overland companies of the day.

Mary Homsley lies in a sandy grave marked by the original headstone now encased in glass and mounted in a concrete pyramid. A passing cowboy discovered the grave in 1925 and alerted the landowner, Clarke Rice. Returning to the site, Rice found the base of the headstone still buried in the ground. The mended stone was encased in the monument and dedicated with great ceremony on Memorial Day, 1926, with well over 500 people attending.

Contacted in Portland, Laura Homsley Gibson could not remember her mother’s death, only that her father had told her the grave must be somewhere in Wyoming. “Father seldom talked about it. Of our mother we only knew that she had been a victim of measles and that she had been buried somewhere along the way.”

Sources

- Anonymous. “Deaths on the Plains.” Missouri Weekly Sentinel. Columbia, Mo. July 22, 1852. Vol. 1. No. 22. p.1, col. 8.

- Anonymous. “Pioneer’s Grave Gives Up Secret.” Morning Oregonian. Portland, Ore.. Jan. 11, 1926. Vol. LXIV, No. 20. p. 1, col. 6.

- Anonymous. “Baker Resident Survivor of Emigrant Train of ’52.” The Sunday Oregonian. Portland, Ore. January 17, 1926. p. 7. col. 5.

- Lockley, Fred. “Lura Homsley Gibson.” Oregon Journal, August 12, 1932. Reprinted in Helm, Mike, ed. Conversations with Pioneer Women. Eugene, Ore.: Rainy Day Press.

- Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. “Mary Homsley Grave.” Emigrant Trails Throughout Wyoming website, accessed April 7, 2017 at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/trailsdemo/mary_homsley.htm.

Illustrations

- All photos are from the author’s collections. Used with permission and thanks.