- Home

- Encyclopedia

- George Ostrom’s War: A Wyoming Soldier-artist S...

George Ostrom’s War: A Wyoming Soldier-artist Serves in France

Soldier, artist, bugler, wolf killer and conservationist George Nicholas Ostrom was born in 1888, in Spencer, Iowa, a small town in the northwestern part of the state. After playing in a band in Iowa, homesteading in North Dakota, driving cattle in Texas and working as an artist in Minneapolis, 25-year old George eventually moved with his widowed mother to the hamlet of Springwillow, 20 miles east of Sheridan, Wyo., in 1913.

Doubtless to fill his pockets with some additional spending money, young George joined Sheridan’s National Guard Company D. That same year he acquired a colt, “a very beautiful sorrel, two white stockings and silver mane and tail and a blazed face,” he remembered years later, that he named Redwing. As a young man, George showed considerable artistic and musical talent, and received a limited amount of professional art training.

On June 18, 1916, the Wyoming National Guard was activated for service on the Mexican border. By that time, George was Staff Sgt. Ostrom, the company bugler. As a bugler, George was responsible for signaling all military events using bugle calls.

Leaving his beloved colt, Redwing, in pasture at the family homestead, George trained at Camp Kendrick on the grounds of the Cheyenne Frontier Days from June to September 1916. He then served at Camp Deming in Deming, N.M., from Sept. 30, 1916, through March 1, 1917.

Congress declared war on Germany April 7, 1917. Ostrom enjoyed a pleasant three weeks’ vacation at home before he was recalled to federal service, eventually finding himself on the western front of the Great War. In France between July and November 1918, Ostrom’s unit, Battery E of the 148th Field Artillery participated in every major campaign of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF).

During his World War I service, a contest was held in the battalion to design a distinctive unit emblem. George created what may be the earliest rendition of Wyoming’s famed “bucking broncho,” as he spelled it, using military black camouflage paint on the head of a drum. He had managed to smuggle Redwing with him to France, and based the image on his colt.

When George showed up with his drawing, the contest was immediately terminated, and he was declared the unanimous winner. Ostrom’s iconic emblem, used on 148th Field Artillery guns and vehicles during WWI, eventually would be redrawn in 1935 by artist Allen True at the direction of Wyoming Secretary of State Lester Hunt for use on Wyoming’s license plates. The first plates were issued in 1936 and the state has used the image ever since.

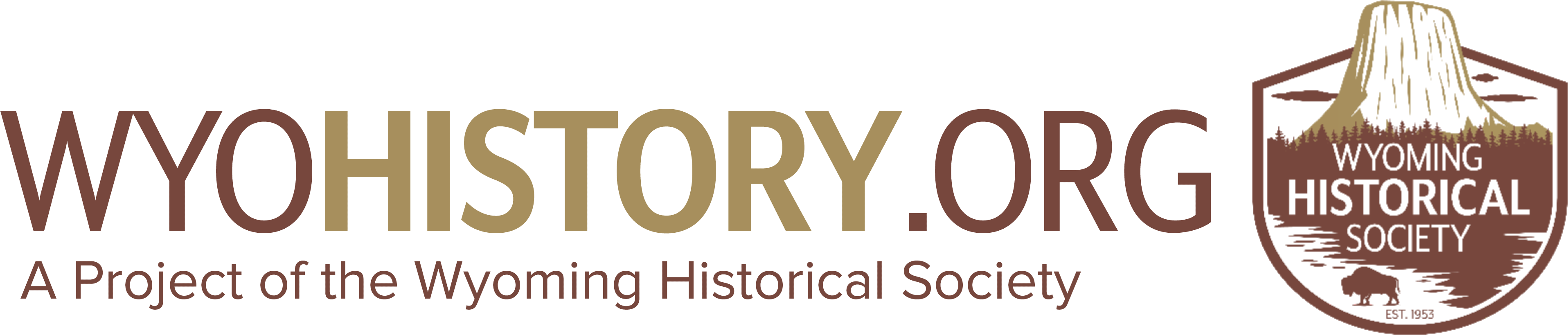

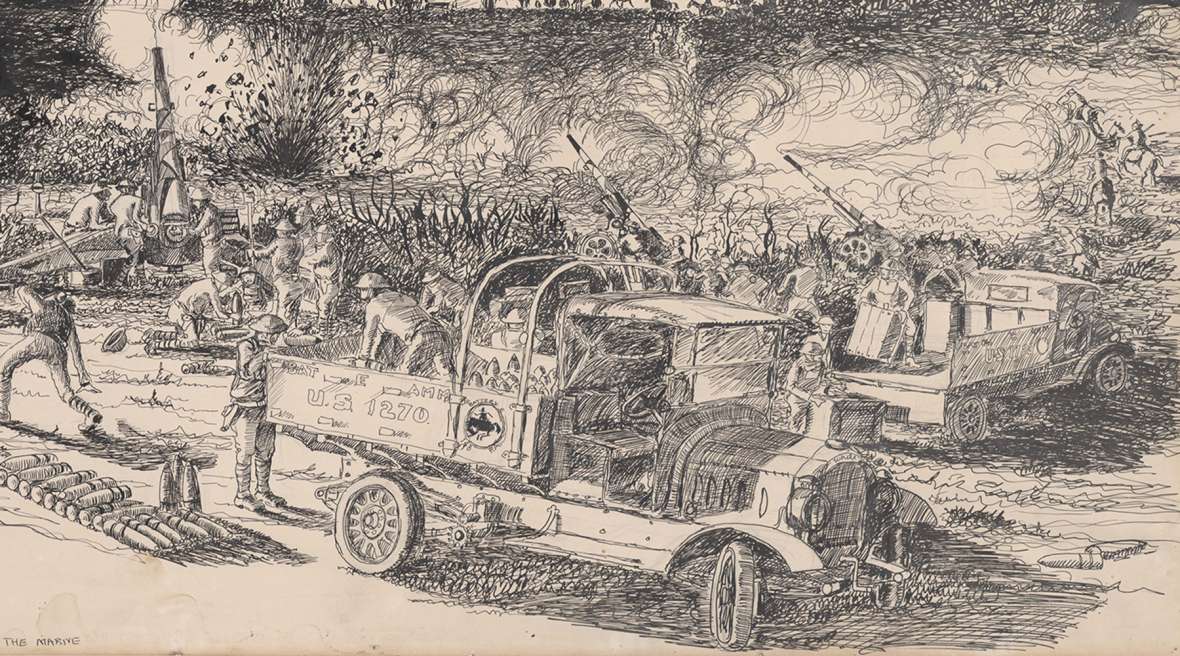

Throughout his military service on the Mexican border and in France, Ostrom prepared nearly 20 drawings of military life—in combat and behind the lines. He originally made these sketches in pencil in the field, on whatever paper he could scrounge. His son, George Ostrom Jr., recalls that after he returned home, his father would spend his evenings inking in the pencil sketches on the family’s kitchen table.

Following his discharge in 1919, George returned to Sheridan, and initially hunted wolves. At the time, the state of Wyoming still paid bounties on wolves, ranging, he remembered, from $100 to $500, a healthy paycheck. Wolves preyed on livestock, and the federal government employed full-time wolf hunters in the West. Ostrom was one of these wolf hunters, serving with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Biological Survey of Predatory Animal Control from 1919 through 1929, by which time the wolf had been all but eliminated from the state.

Ostrom also worked as a commercial artist, painting signs for the city of Sheridan and highway billboards, and created a wealth of art based on his own experiences as a soldier, hunter, rancher, musician and cowboy.

Later in his life, Ostrom regretted his role in destroying the wolf population of Wyoming and became an active conservator, urging their return to the state. He preserved the lives and activities of wolves, with which he was intimately familiar as one of Wyoming’s last wolf hunters, through numerous drawings.

Today, his sketches are considered a national treasure of soldier art, and his wildlife and Wyoming artwork are considered among the finest created by a Wyoming artist.

Ostrom was active in veterans’ organizations and bands throughout his life. He was a popular character at veterans’ reunions, where with a stick of chalk he was known to draw the “bucking broncho” on sidewalks for drinks. George and his bugle were a fixture at Wyoming veterans’ ceremonies and funerals.

He died in Sheridan in 1982 at the age of 97. His family remains in Sheridan, and has entrusted his military drawings and artifacts with the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum in Casper.

Resources

-

Sources

- “Chauchat.” Wikipedia, accessed May 18, 2017 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chauchat.

- “Gray Wolf Timeline for the Contiguous United States.” International Wolf Center, accessed may 16, 2017 at http://www.wolf.org/wow/united-states/gray-wolf-timeline/.

- Hein, Rebecca. “Wyoming’s Long-lived bucking horse.” WyoHistory.org, accessed May 16, 2017 at /encyclopedia/wyomings-long-lived-bucking-horse.

- Ostrom, George, Jr. and Ostrom family, Sheridan, Wyoming. Informal conversations with author, 2017.

- Slack, Judy. George Nicholas Ostrom: Pioneer, Preservationist, Painter, 1888-1982. Sheridan, Wyo.: Big Horn City Historical Society and Sheridan County Historical Society, 2013.

Illustrations

The photo and the drawings are all from the collections of the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum in Casper, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks. Ostrom’s enormously detailed drawings are quite large, some of them 30 inches wide or more. They will be on display in a special show at the Nicolaysen Art Museum in Casper, Wyo., from Oct. 6, 2017 through Jan. 14, 2018.